Anti-Fascism and Democracy in the 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Satisfaction, Political Knowledge and the Acceptance of Clientelism in a New Democracy

Democratization ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fdem20 Dissatisfied, uninformed or both? Democratic satisfaction, political knowledge and the acceptance of clientelism in a new democracy Sergiu Gherghina, Inga Saikkonen & Petar Bankov To cite this article: Sergiu Gherghina, Inga Saikkonen & Petar Bankov (2021): Dissatisfied, uninformed or both? Democratic satisfaction, political knowledge and the acceptance of clientelism in a new democracy, Democratization, DOI: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1947250 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1947250 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 07 Jul 2021. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fdem20 DEMOCRATIZATION https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1947250 RESEARCH ARTICLE Dissatisfied, uninformed or both? Democratic satisfaction, political knowledge and the acceptance of clientelism in a new democracy Sergiu Gherghina a, Inga Saikkonen b and Petar Bankov a aDepartment of Politics and International Relations, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK; bSocial Science Research Institute, Åbo Akademi University, Turku, Finland ABSTRACT In many countries, voters are targeted with clientelistic and programmatic electoral offers. Existing research explores the demand side of clientelism, but we still know very little about what determines voters’ acceptance of clientelistic and programmatic electoral offers. This article builds a novel theoretical framework on the role that democratic dissatisfaction and political knowledge play in shaping voters’ acceptance of different types of electoral offers. We test the implications of the theory with a survey experiment conducted after the 2019 local elections in Bulgaria. -

Ordinances—1934

Australian Capital Territory Ordinances—1934 A chronological listing of ordinances notified in 1934 [includes ordinances 1934 Nos 1-26] Ordinances—1934 1 Sheriff Ordinance Repeal Ordinance 1934 (repealed) repealed by Ord1937-27 notified 8 February 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 8) sch 3 commenced 8 February 1934 (see Seat of Government 23 December 1937 (Administration) Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 2 * Administration and Probate Ordinance 1934 (repealed) repealed by A2000-80 notified 8 February 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 8) sch 4 commenced 8 February 1934 (see Seat of Government 21 December 2000 (Administration) Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 3 Liquor (Renewal of Licences) Ordinance 1934 (repealed) repealed by Ord1937-27 notified 8 February 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 9) sch 3 commenced 8 February 1934 (see Seat of Government 23 December 1937 (Administration) Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 4 Oaths Ordinance 1934 (repealed) repealed by Ord1984-79 notified 15 February 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 10) s 2 commenced 15 February 1934 (see Seat of Government 19 December 1984 (Administration) Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 5 Dogs Registration Ordinance 1934 (repealed) repealed by Ord1975-18 notified 1 March 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 13) sch commenced 1 March 1934 (see Seat of Government (Administration) 21 July 1975 Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 6 * Administration and Probate Ordinance (No 2) 1934 (repealed) repealed by A2000-80 notified 22 March 1934 (Cwlth Gaz 1934 No 17) sch 4 commenced 22 March 1934 (see Seat of Government (Administration) 21 December 2000 Act 1910 (Cwlth), s 12) 7 Advisory -

Download/Print the Study in PDF Format

GENERAL ELECTION IN GREECE 7th July 2019 European New Democracy is the favourite in the Elections monitor Greek general election of 7th July Corinne Deloy On 26th May, just a few hours after the announcement of the results of the European, regional and local elections held in Greece, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA), whose party came second to the main opposition party, New Analysis Democracy (ND), declared: “I cannot ignore this result. It is for the people to decide and I am therefore going to request the organisation of an early general election”. Organisation of an early general election (3 months’ early) surprised some observers of Greek political life who thought that the head of government would call on compatriots to vote as late as possible to allow the country’s position to improve as much as possible. New Democracy won in the European elections with 33.12% of the vote, ahead of SYRIZA, with 23.76%. The Movement for Change (Kinima allagis, KINAL), the left-wing opposition party which includes the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), the Social Democrats Movement (KIDISO), the River (To Potami) and the Democratic Left (DIMAR), collected 7.72% of the vote and the Greek Communist Party (KKE), 5.35%. Alexis Tsipras had made these elections a referendum Costas Bakoyannis (ND), the new mayor of Athens, on the action of his government. “We are not voting belongs to a political dynasty: he is the son of Dora for a new government, but it is clear that this vote is Bakoyannis, former Minister of Culture (1992-1993) not without consequence. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

Presentation Slides

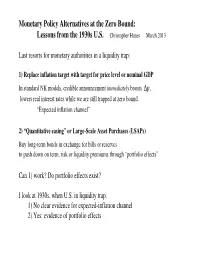

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2010 Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Meddles, Erik, "Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism" (2010). All Regis University Theses. 544. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/544 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

The Dutch Internationalist Communists and the Events in Spain (1936–7)

chapter 9 The Dutch Internationalist Communists and the Events in Spain (1936–7) While the civil war in Spain did not cause a crisis in the gic, it nonetheless had a profound importance in the group’s history. It was the test-bed of the Dutch group’s revolutionary theory, confronted with a civil war which was to prepare the Second World-War, in the midst of revolutionary convulsions and an atmosphere of ‘anti-fascist’ popular fronts. Although often identified with anarchism, Dutch ‘councilism’ vigorously set itself apart from this current and denounced not its weaknesses, but its ‘passage into the camp of the bourgeoisie’. The gic defended a political analysis of the ‘Spanish revolution’ close to that of the Italian communist left. Finally, the events in Spain gave rise to the gic’s last attempt before 1939 to confront the revolutionary political milieu to the left of Trotskyism in Europe. This attempt was not without confusion, and even political ambiguity. Following the creation of the Republic, the internationalist Dutch commun- ists followed the evolution of the Spanish situation with great care. In 1931, the gic denounced not only the Republican bourgeoisie, which supported the Socialist Party of Largo Caballero, but also the anarchist movement. The cnt abandoned its old ‘principle’ of hostility to electoralism, and had its adherents vote en masse for Republican candidates. Far from seeing the cnt as a compon- ent of the workers’ movement, the gic insisted that anarcho-syndicalism had crossed the Rubicon with its ‘collaboration with bourgeois order’. The cnt had become ‘the ally of the bourgeoisie’.As an anarcho-syndicalist current, and thus a partisan of trade-unionism, the political action of the cnt could only lead to a strengthening of capitalism. -

Amadeo Bordiga and the Myth of Antonio Gramsci

AMADEO BORDIGA AND THE MYTH OF ANTONIO GRAMSCI John Chiaradia PREFACE A fruitful contribution to the renaissance of Marxism requires a purely historical treatment of the twenties as a period of the revolutionary working class movement which is now entirely closed. This is the only way to make its experiences and lessons properly relevant to the essentially new phase of the present. Gyorgy Lukács, 1967 Marxism has been the greatest fantasy of our century. Leszek Kolakowski When I began this commentary, both the USSR and the PCI (the Italian Communist Party) had disappeared. Basing myself on earlier archival work and supplementary readings, I set out to show that the change signified by the rise of Antonio Gramsci to leadership (1924-1926) had, contrary to nearly all extant commentary on that event, a profoundly negative impact on Italian Communism. As a result and in time, the very essence of the party was drained, and it was derailed from its original intent, namely, that of class revolution. As a consequence of these changes, the party would play an altogether different role from the one it had been intended for. By way of evidence, my intention was to establish two points and draw the connecting straight line. They were: one, developments in the Soviet party; two, the tandem echo in the Italian party led by Gramsci, with the connecting line being the ideology and practices associated at the time with Stalin, which I label Center communism. Hence, from the time of Gramsci’s return from the USSR in 1924, there had been a parental relationship between the two parties. -

Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with Specific Reference to the Activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts

Mother Russia and the Socialist Fatherland: Women and the Communist Party of Canada, 1932-1941, with specific reference to the activism of Dorothy Livesay and Jim Watts by Nancy Butler A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November 2010 Copyright © Nancy Butler, 2010 ii Abstract This dissertation traces a shift in the Communist Party of Canada, from the 1929 to 1935 period of militant class struggle (generally known as the ‘Third Period’) to the 1935-1939 Popular Front Against Fascism, a period in which Communists argued for unity and cooperation with social democrats. The CPC’s appropriation and redeployment of bourgeois gender norms facilitated this shift by bolstering the CPC’s claims to political authority and legitimacy. ‘Woman’ and the gendered interests associated with women—such as peace and prices—became important in the CPC’s war against capitalism. What women represented symbolically, more than who and what women were themselves, became a key element of CPC politics in the Depression decade. Through a close examination of the cultural work of two prominent middle-class female members, Dorothy Livesay, poet, journalist and sometime organizer, and Eugenia (‘Jean’ or ‘Jim’) Watts, reporter, founder of the Theatre of Action, and patron of the Popular Front magazine New Frontier, this thesis utilizes the insights of queer theory, notably those of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Judith Butler, not only to reconstruct both the background and consequences of the CPC’s construction of ‘woman’ in the 1930s, but also to explore the significance of the CPC’s strategic deployment of heteronormative ideas and ideals for these two prominent members of the Party. -

October 31, 1956 Draft Telegram to Italian Communist Leader Palmiro Togliatti

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified October 31, 1956 Draft telegram to Italian Communist Leader Palmiro Togliatti Citation: “Draft telegram to Italian Communist Leader Palmiro Togliatti,” October 31, 1956, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, TsKhSD, F. 89, Per. 45, Dok. 14 and in The Hungarian Quarterly 34 (Spring 1993), 107.1 http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/111974 Summary: Draft telegram from the CPSU CC to Italian Communist Leader Palmiro Togliatti on the Soviet leadership's position on the situation in Hungary. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Workers of the World, Unite! Top Secret Communist Party of the Soviet Union CENTRAL COMMITTEE No P 49/69 To Comrade Shepilov (M[inistry] of F[oreign] A[ffairs]) and to Comrade Vinogradov Extract from Minutes No. 49, taken at the October 31, 1956 meeting of the Presidium of the CC Draft of a telegram to be sent to Comrade Togliatti, The CC approves the attached text of a telegram to be sent to Comrade Togliatti in con-nection with the Hungarian situation. Secretary of the CC To Paragraph 69 of Minutes No. 49 Top Secret ROME For Comrade TOGLIATTI In your evaluation of the situation in Hungary and of the tendencies of development of the Hungarian Government toward a reactionary development, we are in agreement with you. According to our information, Nagy is occupying a two-faced position and is falling more and more under the influence of the reactionary forces. For the time being we are not speaking out openly against Nagy, but we will not reconcile ourselves with the turn of events toward a reactionary debaucher Your friendly warnings regarding the possibility of the weakening of the unity of the collective leadership of our party have no basis. -

Workers Power and the Spanish Revolution

Workers Power and the Spanish Revolution In Spain’s national elections in February Each sindicato unico had “sections” that of 1936, a repressive right-wing government had their own assemblies and elected shop was swept out of office and replaced by a stewards (delegados). In manufacturing coalition of liberals and socialists. Taking industries like textile or metalworking, advantage of a less repressive environment, there was a “section” for each firm or plant. Spain’s workers propelled the largest strike In the construction industry, the “sections” wave in Spanish history, with dozens of corresponded to the various crafts. All of the citywide general strikes and hundreds of autonomous industrial unions in a city or partial strikes. By the end of June a million county (comarca) were grouped together into workers were out on strike. a local labor council (federación local). Barely a month after the election, the Land The unions were part of a larger context of Workers Federation led 80,000 landless laborers movement institutions. The libertarian Left in Spain into a seizure of three thousand farms in the also organized alternative schools and an extensive “Spanish Siberia” — the poverty-stricken region of network of ateneos — storefront community Estremadura1. With the country at a high pitch of centers. The ateneos were centers for debates, debate over its future, political polarization was cultural events, literacy classes (between 30 and 50 punctuated by tit-for-tat killings of Right and Left percent of the population was illiterate in the ‘30s), activists. With right-wing politicians openly calling and so on. A characteristic idea of Spanish for an army takeover, the widely anticipated army anarchism was the empowerment of ordinary coup began in Spain on July 19th.