Comparative Politics: from Aristotle to the New Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

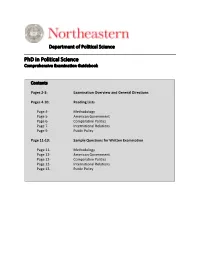

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Coming in the NEXT ISSUE

Association News contributors to the international scientific DBASSE can be accessed at http://sites. community. Nearly 500 members of the nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/index. Coming NAS have won Nobel Prizes” (See http:// htm. Presiding over DBASSE presently nasonline.org/about-nas/mission). is political scientist Kenneth Prewitt. in the For the past century and a half, mem- Scholars who are not NAS members also NEXT bers have investigated and responded to regularly participate as members of NAS questions posed by our national leaders committees, and we urge all political sci- ISSUE as a form of service to the nation without entists to give serious consideration to financial recompense. As Ralph Cicerone, these requests. A preview of some of the articles in the president of the NAS, never fails to relate The discussion at this year’s meeting April 2014 issue: to new members at the annual installation of NAS-member political scientists at ceremony, while our advice is often solic- the APSA convention centered on how to SYMPOSIUM ited—its first report to the Lincoln admin- effectively transmit the best social science US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION istration addressed whether our country knowledge to the government through FORECASTING should adopt the metric system, and sent the NRC. One issue facing the NRC in Michael Lewis-Beck and back a consensus “yes” answer—this ad- general and the DBASSE in particular Mary Stegmaier, guest editors vice is not always followed. Scientific is that by charter the NAS is not permit- FEATURES objectivity is the goal of the Academy, not ted to solicit contracts from government political advocacy. -

American Political Science Review Vol

Vol.72 June 1978 No. 2 THE CONFERENCE BOARD INC. LIBRARY . JUL 191978 ^ „ 845 THIRD AVENUE ' I ^\\XX NEW YORK, N.Y. 10022 Ml 1%^ https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms American Political Science Review , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 27 Sep 2021 at 13:02:49 , on 170.106.202.8 . IP address: Published Quarteriy by https://www.cambridge.org/core The American Political Science Association -£ https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400155819 Downloaded from SEPTEMBER is closer than you think... Adopt these fine texts now . Lineberry AMERICAN PUBLIC POLICY What Government Does and What Difference It Mates This introductory public policy text focuses on the twin themes of policy .', „" analysis and the application of policy to key political issues. Using a two-part -' format, the book first discusses theories and methods of domestic policy * ' , analysis and then covers application of these techniques in four areas: cities, ' crime, inequality, and the management of scarcity. 296 pages; $7.95/paper. January 1978. ISBN 0-06-044013-9. https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms Lineberry & Sharkansky URBAN POLITICS AND PUBLIC POLICY Third Edition The new Third Edition features an even stronger policy approach, with new treatments of the political economy and sociology of cities and retains the extensive treatment of mass politics and elite decision making. Recent issues and data have been incorporated as well as discussions of urban fiscal crises, the sun-belt cities, public services, growth and decay as policy problems, and inequality. 416 pages; $1O.95/paper. February 1978. ISBN 0-06-044029-5. -

American Public Policy Syllabus

V. American Public Policy Prof. William Lowry William Lowry is a Professor of Political Science at Washington University. He received his PhD in Political Science from Stanford University in 1988. He studies American politics, environmental policy, and natural resource issues. He is the author of five books as well as numerous articles. Description This course considers basic aspects of public policy, mostly but not entirely in the American context. We will discuss prominent theories of policymaking, major stages of the policy process, review some classic works, discuss recent contributions, and focus our substantive discussions on an ongoing research project largely of your choosing. The purpose of the class is to provide a broad overview of the American policy process and to facilitate empirical application of major theories. Requirements The class will be conducted as a seminar. We should all be able to learn from each other. As such, attendance and participation in discussion is essential. We will all have to keep up on the reading in order to contribute. Besides participation, your major requirement is the research project. Different parts of the paper will be turned in at various points during the semester with the final paper due 4/21. Grades will be based on participation and this research project. Reading Theories of the Policy Process 2nd ed. by Sabatier; Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies by Kingdon Implementation by Pressman and Wildavsky Introduction Paul Sabatier. 2007. Theories of the Policy Process. Chapter 1. Overview of Policy Theory Garrett Hardin. 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons in Science Elinor Ostrom. 2007. -

GOVT 2305: American Politics Field Seminar Fall 2016

GOVT 2305: American Politics Field Seminar Fall 2016 Instructors: Dan Carpenter: Office hours are on Thursdays, 1-4, CAPS Conference Room Jon Rogowski: Office hours are Tuesdays, 3-4, CGIS 420 Wednesdays 2-4pm Location: Knafel 401 The purpose of this course is to introduce doctoral students to the major themes and some of the best scholarship in the political science literature on American Politics. The readings for 2305 typically form the core of students’ subsequent reading lists for major or minor prelims in American. Still, there is much in the study of American politics that is not represented here, indeed that political scientists have failed to take up. Along the way, we will want to identify what we take to be some of the most important but neglected questions. What issues should motivate the next generation of research in this field? What theoretical and methodological approaches might be appropriate to studying them? The most important requirement of the course is that you read the assigned readings for each week carefully and critically. The syllabus contains *starred* readings that are mandatory, and a large set of additional reading if you want to go deeper into a given topic or set of related arguments. This syllabus can therefore serve as a guide for future readings, and you can also discuss these readings with your advisors if you plan on taking the American Prelim. The starred readings will serve as the primary focus of our weekly discussions, though we will rarely be able to talk about them all in the time allotted. -

Public Opinion, Rational Choice and the New Institutionalism: Rational Choice As a Critical Theory of the Link Between Public Opinion and Public Policy

Public Opinion, Rational Choice and the New Institutionalism: Rational Choice as a Critical Theory of the Link Between Public Opinion and Public Policy Derry O’Connor Université Laval Paper Prepared for Workshop No. 6: “Public Opinion, Polling, and Public Policy”, Canadian Political Science Association Conference, Winnipeg, June 3-5, 2004. (May 14, 2004 Version) Abstract Studies on the nature of public opinion and its impact on public policy, while borrowing from Rational Choice’s methodological individualism and rational actor assumptions, often fail to take into account the wider implications of rational choice theorizing for the Opinion-Policy Nexus. In this paper we use Rational Choice Theory to criticize the mass society approach to Public Opinion and Policy. Particularly important, but often overlooked by Public Opinion scholars, are Public Choice findings on rational ignorance, the spatial theory of preferences, Intransitivity, Heresthetics, and Collective Action Problems. These theories suggest the vulnerability of mass-opinion, a positivist construct, to elite rhetorical manipulation. Riker’s conclusion in favour of Liberalism over Populism, paralleled in the debate over the need for elite leadership of the public versus democratic responsiveness to polls, suggests that Public Opinion scholars might also reconsider the validity of mass opinion polls as the dominant construct of public opinion. Also within the Rational Choice framework, the findings of Neo-Institutionalism may suggest the applicability of some alternative forms of public input into the policy process. Résumé Bien qu’elles empruntent à la perspective du choix rationnel l’individualisme méthodologique et les prémisses de rationalité de l’acteur, les études sur la nature de l’opinion publique et son impact sur les politiques publiques ne tiennent pas toujours compte des implications plus larges reliées à l’utilisation de la perspective du choix rationnel eu égard aux liens entre les politiques et l’opinion de masse. -

POLS-Y657 Comparative Political Behavior

POLS-Y657 Comparative Political Behavior Course Overview This seminar provides an introduction to some of the major themes in political behavior, including partisanship, elections, political attitudes, information, ideology, participation, and the role of the mass media in shaping the public’s political beliefs and orientations. We will consider how well our theories explain political outcomes in both democracies and autocracies. Instructor Jason Wu Woodburn Hall 323 [email protected] Office Hours: By Appointment Requirements and Grading Students are expected to regularly attend class, actively contribute to class discussions, and com- plete the reading assignments. In addition, each student will be assigned the task of introducing and briefly critiquing one of the readings each class. In these overviews, students should highlight the question, theory, research design, results, and implications of their reading as well as note any major flaws. For the writing component of this course, students will be required to write either a research paper or a research design/proposal. If it is a paper, it should be part of a project that is ultimately publishable, although you do not need to complete all parts of the project for this class. The paper should either be an original research paper or show substantial progress from previous work. If you are interested in co-authoring a paper with another student, please discuss that option with me in advance. If students select the design option, they should submit a research proposal which identifies an important research question, surveys the relevant literature, identify a potential contribution, present a theoretical argument, and propose a design for testing that argument (which would ideally entail collecting original data). -

Creative Synthesis: a Model of Peer Review, Reflective Equilibrium and Ideology Formation ∗

Creative Synthesis: A Model of Peer Review, Reflective Equilibrium and Ideology Formation ∗ Hans Noel Associate Professor Georgetown University [email protected] Department of Government Intercultural Center 681 Washington, D.C. 20057 August 24, 2015 Abstract The formation of ideology can be modeled as a communication game that combines actors' psychological predispositions and their rational self-interest. I argue that we can explain ideo- logical development by modeling the way in which political thinkers reason from first principles, and how they fail to ignore their own psychological and interest-based biases. I begin with a distributive model to provide a structure for people's interests and their psychological traits, and add in a model of reason (Rawls, 2001) to explain how those interests and traits will shape the development of ideology. The model develops the framework, based on the practice of peer review. This framework creates a tournament of potential ideologies and traces whether such a mechanism can explain the development of multiple competing ideologies. ∗Paper prepared for the American Political Science Association's Annual Meeting in San Francisco, Calif., Sept. 3-6, 2015. I would like to thank Kathleen Bawn, Sean Gailmard, Alexander Hirsch, Ethan Kaplan, Ken Kollman, Jeff Lewis, Skip Lupia, Chlo´eYelena Miller, John Patty, Tom Schwartz, Brian Walker, John Zaller and seminar participants at the University of Michigan and Georgetown University for useful advice and comments on earlier versions of this project. \[T]he shaping of belief systems of any range into apparently logical wholes that are credible to large numbers of people is an act of creative synthesis characteristic of only a miniscule proportion of any population." { Philip Converse, The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics, 1964, p. -

Converse, Philip E. 2000. ``Assessing the Capacity of Mass Electorates

P1: FRD April 18, 2000 16:15 Annual Reviews AR097-14 Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2000. 3:331–53 Copyright c 2000 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved ASSESSING THE CAPACITY OF MASS ELECTORATES Philip E. Converse Department of Political Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105; e-mail: [email protected] Key Words elections, issue voting, political information, democratic theory, ideology ■ Abstract This is a highly selective review of the huge literature bearing on the capacity of mass electorates for issue voting, in view of the great (mal)distribution of political information across the public, with special attention to the implications of information heterogeneity for alternative methods of research. I trace the twists and turns in understanding the meaning of high levels of response instability on survey policy items from their discovery in the first panel studies of 1940 to the current day. I consider the recent great elaboration of diverse heuristics that voters use to reason with limited information, as well as evidence that the aggregation of preferences so central to democratic process serves to improve the apparent quality of the electoral response. A few recent innovations in design and analysis hold promise of illuminating this topic from helpful new angles. Never overestimate the information of the American electorate, but never underestimate its intelligence. (Mark Shields, syndicated political columnist, citing an old aphorism) INTRODUCTION Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 2000.3:331-353. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org In 1997, I was asked to write on the topic “How Dumb Are the Voters Really?” Access provided by University of California - Davis on 09/14/15. -

Prof. David Canon Fall Semester 2019 Political Science 904 Office Hours

Prof. David Canon Fall Semester 2019 Political Science 904 Office Hours: T+Th 4-5 p.m., Monday, 1:20-3:15, 422 North Hall and by appointment [email protected], 263-2283 413 North Hall CLASSICS IN AMERICAN GOVERNMENT COURSE DESCRIPTION The purpose of this seminar is to introduce the core questions, concepts, and theories of the field through the "classic" works. I developed this seminar in response to graduate students who believed that too many graduate courses in American politics had lost sight of the forest by examining the trees in too much detail (or in some cases, by putting parts of each branch and leaf under a microscope). Advanced seminars typically focus on cutting edge research and often assume the reader is familiar with the theoretical debates and underlying issues. However, most graduate students have not had the opportunity to read the original works that motivate contemporary research. This seminar will provide that opportunity. A related issue concerns the methodology employed in "classic" and current research. Many first-year students (and other advanced students who have not had statistics) have difficulty plowing through the technical work that is assigned in many American politics seminars. The onslaught of numbers, equations, and formal models from the APSR or AJPS can be pretty daunting. The classic works assigned here rarely employ any math more sophisticated than descriptive statistics or simple correlation. While I believe it is important to master the more technical approaches, a prior requirement is to understand the important theories and issues in the field. While the primary aim of the seminar is to introduce you to the central questions and concepts in the field, we will spend some time each week developing your research skills. -

Opinion and Action in the Realm of Politics

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR OPINION AND ACTION IN THE REALM OF POLITICS DON A LD R. KINDER, University of Michigan Fewconcepts are more central to the analysis of democra public opinion into political action-from a social psycho tic politics than public opinion. It is, or seems to be, a com logical perspective . pletely familiar idea, simply part of the landscape of poli My ambition is to provide a set of analytic categories tics we take for granted today. Yet to the specialist, getting helpful in organizing the vast empirical literature on public a grip on public opinion is not that easy. Public opinion is, opinion. In this respect I am trying to follow the admoni as Converse (I 975) once put it, "impalpable," "amor tions of Max Weber, who argued that the creation of clear phous ," and ·'mercurial" (p . 77). Public opinion is hard to and useful concepts was social theory's noblest aspiration. pin down. Clear and useful concepts are certainly what we need here; Conceding that my subject is complicated and difficult, in their absence, making sense of the empirical literature I nevertheless hope to say something systematic and intel on public opinion is a daunting and perhaps impossible ligible about it here. My particular topic is public opinion, task. It is alarming , actually : thousands of reports have but the chapter can be read more broadly as another install been published; scores more no doubt on their way to com ment in the continuing conversation between political sci pletion. In some ways this activity is all to the good; it re ence and social psychology.