Spring 2006 Office: BSB 1115 Hours: W 1:30-3:30

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gether They Form the Backbone of Madison’S Vision for the New Congress

REVISITING AND RESTORING MADISON’S AMERICAN CONGRESS BY SARAH BINDER Looking westward to Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains from his Montpelier library, James Madison in 1787 drafted the Virginia Plan—the proposal he would bring to the summer’s Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Long after ratification of the Constitution—and after the Du Pont family had suffocated Montpelier in pink stucco— preservationists returned to Montpelier to restore Madison’s home. Tough to say the same for the U.S. Congress, the institutional lynchpin of Madison’s constitutional plan. True, Congress has proved an enduring political institution as Madison surely intended. But Congress today often misses the Madisonian mark. The rise of nationalized and now ideologically polarized parties challenges Madison’s constitutional vision: Lawmakers today are more often partisans first, legislators second. In this paper, I explore Madison’s congressional vision, review key forces that have complicated Madison’s expectations, and consider whether and how Congress’s power might (ever) be restored. MADISON’S CONGRESSIONAL VISION Madison embedded Congress in a broader political system that dispersed constitutional powers to separate branches of government, but also forced the branches to share in the exercise of many of their powers. In that sense, it is difficult to isolate Madison’s expectations for Congress apart from his broader constitutional vision. Still, two elements of Article 1 are particularly important for distilling Madison’s plan for the new Congress. First, Madison believed (or hoped) that his constitutional system would channel lawmakers’ ambitions, creating incentives for legislators to remain responsive to the broad political interests that sent them to Congress in the first place. -

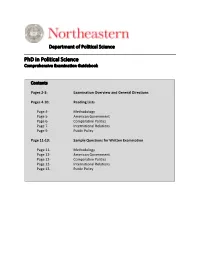

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Teaching Portfolio Andrew Dilts, Ph.D

Teaching Portfolio Andrew Dilts, Ph.D. Teaching Portfolio Andrew Dilts, Ph.D. Pedagogical Statement 1 Teaching History 4 Selected Comments from Teaching Evaluations 5 Summary Statistics from Teaching Evaluations 8 Sample Syllabi 9 Pedagogical Statement My approach to teaching is centered on developing my students’ skills of critical engagement of texts, phenomena, and discursive objects of analysis so that they can ultimately employ those skills to understand, interpret, and respond to the world around them, as well as their own selves. In this sense, I see my teaching as part of a larger project of enabling students to develop their entire selves, reflecting their own multiplicity, plurality, and difference. Practically, this mean that the most important thing that I want to impart to my students is that any text, practice, discourse, or object of thoughtful analysis that is worth thinking and writing about calls for a sympathetic critique. By this I mean that texts of all forms require something akin to what Nietzsche calls an “art of interpretation,” and that the essence of this “art” is to provide careful support from one’s reading first and foremost from within the text itself. My pedagogy is driven by a strong preference for teaching original and primary sources by reading them closely while attending to their historical, social, and political contexts. But above all, I want to teach my students that a critical engagement with a thinker begins with taking them seriously on their own terms, sympathetically and internally. I work for my students to appreciate the power and pleasure of such an approach, and to come away from any seminar, lecture, or advising session with the practical reading and writing skills to put this into practice in their own well-supported reading of a text. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Coming in the NEXT ISSUE

Association News contributors to the international scientific DBASSE can be accessed at http://sites. community. Nearly 500 members of the nationalacademies.org/DBASSE/index. Coming NAS have won Nobel Prizes” (See http:// htm. Presiding over DBASSE presently nasonline.org/about-nas/mission). is political scientist Kenneth Prewitt. in the For the past century and a half, mem- Scholars who are not NAS members also NEXT bers have investigated and responded to regularly participate as members of NAS questions posed by our national leaders committees, and we urge all political sci- ISSUE as a form of service to the nation without entists to give serious consideration to financial recompense. As Ralph Cicerone, these requests. A preview of some of the articles in the president of the NAS, never fails to relate The discussion at this year’s meeting April 2014 issue: to new members at the annual installation of NAS-member political scientists at ceremony, while our advice is often solic- the APSA convention centered on how to SYMPOSIUM ited—its first report to the Lincoln admin- effectively transmit the best social science US PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION istration addressed whether our country knowledge to the government through FORECASTING should adopt the metric system, and sent the NRC. One issue facing the NRC in Michael Lewis-Beck and back a consensus “yes” answer—this ad- general and the DBASSE in particular Mary Stegmaier, guest editors vice is not always followed. Scientific is that by charter the NAS is not permit- FEATURES objectivity is the goal of the Academy, not ted to solicit contracts from government political advocacy. -

American Political Science Review Vol

Vol.72 June 1978 No. 2 THE CONFERENCE BOARD INC. LIBRARY . JUL 191978 ^ „ 845 THIRD AVENUE ' I ^\\XX NEW YORK, N.Y. 10022 Ml 1%^ https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms American Political Science Review , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at 27 Sep 2021 at 13:02:49 , on 170.106.202.8 . IP address: Published Quarteriy by https://www.cambridge.org/core The American Political Science Association -£ https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400155819 Downloaded from SEPTEMBER is closer than you think... Adopt these fine texts now . Lineberry AMERICAN PUBLIC POLICY What Government Does and What Difference It Mates This introductory public policy text focuses on the twin themes of policy .', „" analysis and the application of policy to key political issues. Using a two-part -' format, the book first discusses theories and methods of domestic policy * ' , analysis and then covers application of these techniques in four areas: cities, ' crime, inequality, and the management of scarcity. 296 pages; $7.95/paper. January 1978. ISBN 0-06-044013-9. https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms Lineberry & Sharkansky URBAN POLITICS AND PUBLIC POLICY Third Edition The new Third Edition features an even stronger policy approach, with new treatments of the political economy and sociology of cities and retains the extensive treatment of mass politics and elite decision making. Recent issues and data have been incorporated as well as discussions of urban fiscal crises, the sun-belt cities, public services, growth and decay as policy problems, and inequality. 416 pages; $1O.95/paper. February 1978. ISBN 0-06-044029-5. -

SOC 585: Racial and Ethnic Politics in the US

Spring 2018 Prof. Andra Gillespie 217E Tarbutton 7-9748 [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. (12-2 p.m. the first Wednesdays of the month) or by appointment Emory University Department of Political Science SOC 585/POLS 585 Racial and Ethnic Politics in the US This course is designed to introduce graduate students to some of the canonical readings, both historical and contemporary, in racial and ethnic politics. While African American politics will be a central theme of this course, this course intentionally introduces students to key themes in Latino/a and Asian American politics as well. By the end of the course, students should be conversant in the major themes of racial and ethnic politics in the US. Required Readings The following books have been ordered and are available at the Emory Bookstore: Cathy Cohen. 1999. The Boundaries of Blackness. Michael Dawson. 1994. Behind the Mule. Megan Francis. 2014. Civil Rights and the Making of the Modern American State. Lorrie Frasure-Yokeley. 2015. Racial and Ethnic Politics in American Suburbs. Christian Grose. 2011. Congress in Black and White. Ian Haney-Lopez. 1997, 2007. White By Law. Carol Hardy-Fanta et al. 2016. Contested Transformation: Race, Gender and Political Leadership in 21st Century America. Rawn James. 2013. Root and Branch. Donald Kinder and Lynn Sanders. 1994. Divided by Color. Taeku Lee and Zoltan Hajnal. 2011. Why Americans Don’t Join the Party. Michael Minta. 2011. Oversight. Stella Rouse. 2013. Latinos in the Legislative Process Katherine Tate. 2010. What’s Going On? Katherine Tate. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Political Science Scope and Methods

Political Science Scope and Methods Devin Caughey and Rich Nielsen MIT j 17.850 j Fall 2019 j Th 9:00{11:00 j E53-438 http://stellar.mit.edu/S/course/17/fa19/17.850 Contact Information Devin Caughey Rich Nielsen Email: [email protected] [email protected] Office: E53-463 E53-455 Office Hours: Th 11{12 or by appt. Th 3{4 or by appt. (sign up on my door) (sign up on my door) Course Description This course provides a graduate-level introduction to and overview of approaches to polit- ical science research. It does not delve deeply into normative political theory or statistics and data analysis (both of which are covered in depth by other courses), but it addresses al- most all other aspects of the research process. Moreover, aside from being broadly positivist in orientation, the course is otherwise ecumenical with respect to method and subfield. The course covers philosophy of science, the generation of theories and research questions, con- ceptualization, measurement, causation, research designs (quantitative and qualitative), mixing methods, and professional ethics. The capstone of the course is an original research proposal, a preliminary version of which students (if eligible) may submit as an NSF re- search proposal (at least 8 students have won since 2014). In addition to this assignment, the main requirement of this course is that students thoroughly read the texts assigned each week and come to seminar prepared to discuss them with their peers. Expectations • Please treat each other with respect, listen attentively when others are speak- ing, and avoid personal attacks. -

The President's Dominance in Foreign Policy Making Author(S): Paul E

The President's Dominance in Foreign Policy Making Author(s): Paul E. Peterson Reviewed work(s): Source: Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 109, No. 2 (Summer, 1994), pp. 215-234 Published by: The Academy of Political Science Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2152623 . Accessed: 15/11/2011 00:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Academy of Political Science is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Political Science Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org The President'sDominance in Foreign Policy Making PAUL E. PETERSON In the fall of 1991, George Bush saw his own attorney- general defeated in an off-year Pennsylvania senatorial race. Richard Thornburgh,once a popular governor, fell victim to attacks by Harris Wofford, an aging, politically inexperienced,unabashedly liberal col- lege professor. The Democrats succeeded in a state that had rejected their candidates in every Senate election since 1962. Curiously, the defeat came after Bush had presided over the fall of the Berlin wall, the reunification of Germany, the democratizationof Eastern Europe, -

American Public Policy Syllabus

V. American Public Policy Prof. William Lowry William Lowry is a Professor of Political Science at Washington University. He received his PhD in Political Science from Stanford University in 1988. He studies American politics, environmental policy, and natural resource issues. He is the author of five books as well as numerous articles. Description This course considers basic aspects of public policy, mostly but not entirely in the American context. We will discuss prominent theories of policymaking, major stages of the policy process, review some classic works, discuss recent contributions, and focus our substantive discussions on an ongoing research project largely of your choosing. The purpose of the class is to provide a broad overview of the American policy process and to facilitate empirical application of major theories. Requirements The class will be conducted as a seminar. We should all be able to learn from each other. As such, attendance and participation in discussion is essential. We will all have to keep up on the reading in order to contribute. Besides participation, your major requirement is the research project. Different parts of the paper will be turned in at various points during the semester with the final paper due 4/21. Grades will be based on participation and this research project. Reading Theories of the Policy Process 2nd ed. by Sabatier; Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies by Kingdon Implementation by Pressman and Wildavsky Introduction Paul Sabatier. 2007. Theories of the Policy Process. Chapter 1. Overview of Policy Theory Garrett Hardin. 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons in Science Elinor Ostrom. 2007. -

Proudly for Brooke: Race-Conscious Campaigning in 1960S Massachusetts --Manuscript Draft

Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics Proudly for Brooke: Race-Conscious Campaigning in 1960s Massachusetts --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: JREP-D-16-00087R1 Full Title: Proudly for Brooke: Race-Conscious Campaigning in 1960s Massachusetts Article Type: Research Article Corresponding Author: Richard Johnson Oxford University Oxford, UNITED KINGDOM Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: Oxford University Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Richard Johnson First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Richard Johnson Order of Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: Scholars have credited the victory of Edward Brooke, America's first popularly elected black United States senator, to a 'deracialised' or 'colour-blind' election strategy in which both the candidate and the electorate ignored racial matters. This article revises this prevailing historical explanation of Brooke's election. Drawing from the historical- ideational paradigm of Desmond King and Rogers Smith, this paper argues that Brooke was much more of a 'race-conscious' candidate than is generally remembered. Primary documents from the 1966 campaign reveal that Brooke spoke openly against racial inequality, arguing in favour of racially targeted policies and calling for stronger racial equality legislation. In addition, this paper argues that Brooke's appeals were not targeted primarily to the state's small black population but to liberal whites. Far from ignoring race, internal campaign documents and interviews with campaign staff reveal that Brooke's campaign strategists sought to appeal to white desires to 'do the right thing' by electing an African American. Internal polling documents from the Brooke campaign and newspaper commentaries further demonstrate that a proportion of the white electorate cited Brooke's race as the reason for supporting his candidacy.