THE PAST and PRESENT of COMPARATIVE POLITICS Gerardo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗

Managing Meritocracy in Clientelistic Democracies∗ Sarah Brierleyy Washington University in St Louis May 8, 2018 Abstract Competitive recruitment for certain public-sector positions can co-exist with partisan hiring for others. Menial positions are valuable for sustaining party machines. Manipulating profes- sional positions, on the other hand, can undermine the functioning of the state. Accordingly, politicians will interfere in hiring partisans to menial position but select professional bureau- crats on meritocratic criteria. I test my argument using novel bureaucrat-level data from Ghana (N=18,778) and leverage an exogenous change in the governing party to investigate hiring pat- terns. The results suggest that partisan bias is confined to menial jobs. The findings shed light on the mixed findings regarding the effect of electoral competition on patronage; competition may dissuade politicians from interfering in hiring to top-rank positions while encouraging them to recruit partisans to lower-ranked positions [123 words]. ∗I thank Brian Crisp, Stefano Fiorin, Barbara Geddes, Mai Hassan, George Ofosu, Dan Posner, Margit Tavits, Mike Thies and Daniel Triesman, as well as participants at the African Studies Association Annual Conference (2017) for their comments. I also thank Gangyi Sun for excellent research assistance. yAssistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Washington University in St. Louis. Email: [email protected]. 1 Whether civil servants are hired by merit or on partisan criteria has broad implications for state capacity and the overall health of democracy (O’Dwyer, 2006; Grzymala-Busse, 2007; Geddes, 1994). When politicians exchange jobs with partisans, then these jobs may not be essential to the running of the state. -

Comparative Government

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Syllabi Course Syllabi Fall 9-1-2001 PSC 520.01: Comparative Government Louis Hayes University of Montana - Missoula, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hayes, Louis, "PSC 520.01: Comparative Government" (2001). Syllabi. 7024. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/syllabi/7024 This Syllabus is brought to you for free and open access by the Course Syllabi at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syllabi by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Science 520 COMPARATIVE POLITICS 9/13 Comparative Government and Political Science Robert A Dahl, "Epitaph for a Monument to a Successful Protest, "AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW 1961 763-72 -------------------- ---- ----- 9/20 Systems Approach David Easton, "An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems," WORLD POLITICS (April 1957) 383-400 Gabriel Almond _and G. Bingham Powell, COMPARATIVE POLITICS: A DEVEtOPMENTAL APPROACH, Chapter II 9/27 Structural-functional Analysis William Flanigan and Edwin Fogelman, "Functionalism in Political Science," in Don Martindale, ed. , FUNCTIONALISM IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 111-126 Robert Holt, "A Proposed Structural-Functional Framework for Political Science," in Martindale, 84-110 10/4 Political Legitimacy and Authority Richard Lowenthal, "Political Legitimacy and Cultural Change in West and East" SOCIAL RESEARCH (Autumn 1979), 401-35 Young Kim, "Authority: - Some Conceptual and Empirical Notes" Western Political Quarterly (June 1966), 223-34 10/11 Political Parties and Groups Steven Reed, "Structure and Behavior: Extending Duverger's Law to the Japanese Case," British Journal of Political Science (July 1999) 335-56. -

Review of Review of the Social Edges of Psychoanalysis. Neil J

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 27 Issue 4 December Article 11 December 2000 Review of The Social Edges of Psychoanalysis. Neil J. Smelser. Reviewed by Daniel Coleman. Daniel Coleman University of California, Berkeley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Clinical and Medical Social Work Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Coleman, Daniel (2000) "Review of The Social Edges of Psychoanalysis. Neil J. Smelser. Reviewed by Daniel Coleman.," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 27 : Iss. 4 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol27/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Book Reviews 205 a clear starting point, a way to get grounded and specific guidance for approach the literature. Such a small book (just 159 pages of text) cannot be expected to cover everything completely and the book has some gaps. Most perplexing is Rose's neglect of evaluation in the applications section. After such a useful introduction to evaluation one won- ders why he didn't provide more examples of effective, feasible evaluation designs. Mention is made of cultural competence and inter-cultural issues are featured in the section on peer relationships. Cultural issues in design are less fully treated in the other chapters. The growing field of learning disorders may deserve greater attention than it gets here. Perhaps the development of group technologies has not proceeded to the point where a separate chapter could be written. -

The Revival of Economic Sociology

Chapter 1 The Revival of Economic Sociology MAURO F. G UILLEN´ , RANDALL COLLINS, PAULA ENGLAND, AND MARSHALL MEYER conomic sociology is staging a comeback after decades of rela- tive obscurity. Many of the issues explored by scholars today E mirror the original concerns of the discipline: sociology emerged in the first place as a science geared toward providing an institutionally informed and culturally rich understanding of eco- nomic life. Confronted with the profound social transformations of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the founders of so- ciological thought—Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, Georg Simmel—explored the relationship between the economy and the larger society (Swedberg and Granovetter 1992). They examined the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services through the lenses of domination and power, solidarity and inequal- ity, structure and agency, and ideology and culture. The classics thus planted the seeds for the systematic study of social classes, gender, race, complex organizations, work and occupations, economic devel- opment, and culture as part of a unified sociological approach to eco- nomic life. Subsequent theoretical developments led scholars away from this originally unified approach. In the 1930s, Talcott Parsons rein- terpreted the classical heritage of economic sociology, clearly distin- guishing between economics (focused on the means of economic ac- tion, or what he called “the adaptive subsystem”) and sociology (focused on the value orientations underpinning economic action). Thus, sociologists were theoretically discouraged from participating 1 2 The New Economic Sociology in the economics-sociology dialogue—an exchange that, in any case, was not sought by economists. It was only when Parsons’s theory was challenged by the reality of the contentious 1960s (specifically, its emphasis on value consensus and system equilibration; see Granovet- ter 1990, and Zelizer, ch. -

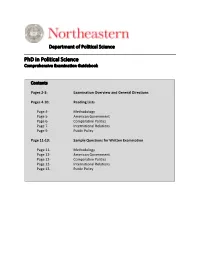

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

Abstract Department of Political Science Westfield

ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE WESTFIELD, ALWYN W BA. HONORS UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX, 1976 MS. LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 1977 THE IMPACT OF LEADERSHIP ON POLITICS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES UNDER EBENEZER THEODORE JOSHUA AND ROBERT MILTON CATO Committee Chair: Dr. F.SJ. Ledgister Dissertation dated May 2012 This study examines the contributions of Joshua and Cato as government and opposition political leaders in the politics and political development of SVG. Checklist of variable of political development is used to ensure objectivity. Various theories of leadership and political development are highlighted. The researcher found that these theories cannot fully explain the conditions existing in small island nations like SVG. SVG is among the few nations which went through stages of transition from colonialism to associate statehood, to independence. This had significant effect on the people and particularly the leaders who inherited a bankrupt country with limited resources and 1 persistent civil disobedience. With regards to political development, the mass of the population saw this as some sort of salvation for fulfillment of their hopes and aspirations. Joshua and Cato led the country for over thirty years. In that period, they have significantly changed the country both in positive and negative directions. These leaders made promises of a better tomorrow if their followers are prepared to make sacrifices. The people obliged with sacrifices, only to become disillusioned because they have not witnessed the promised salvation. The conclusions drawn from the findings suggest that in the process of competing for political power, these leaders have created a series of social ills in SVG. -

![177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2150/177-decentralization-are-implemented-and-enduringneighborhood-organization-structures-social-conditions-and-pol4ical-groundwo-192150.webp)

177] Decentralization Are Implemented and Enduringneighborhood Organization Structures, Social Conditions, and Pol4ical Groundwo

DOCUMENT EESU E ED 141 443 UD 017 044 .4 ' AUTHCE Yates, Douglas TITLE Tolitical InnOvation.and Institution-Building: TKe Experience of Decentralization Experiments. INSTITUTION Yale Univ., New Haven, Conn. Inst. fOr Social and Policy Studies. SEPCET NO W3-41 PUB DATE 177] .NCTE , 70p. AVAILABLEFECM Institution for Social and,Policy Studies, Yale tUniversity,-',111 Prospect Street,'New Haven, Conn G6520. FEES PRICE Mt2$0.83 HC-$3.50.Plus Postage. 'DESCEIPTORS .Citizen Participation; City Government; Community Development;,Community Involvement; .*Decentralization; Government Role; *Innovation;. Local. Government; .**Neighborflood; *Organizational Change; Politics; *Power Structure; Public Policy; *Urban Areas ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to resolve what determines the success or failure of innovations in Participatory government; and,-more precisely what are the dynamics of institution-building by which the 'ideas of,participation arid decentralization are implemented and enduringneighborhood institutions aTe established. To answer these questiOns, a number of decentralization experiments were examined to determine which organization structures, Social conditions, and pol4ical arrangements are mcst conducive io.sucCessful innov,ation and institution -building. ThiS inquiry has several theoretical implications:(1) it.examines the nature and utility of pOlitical resources available-to ordinary citizens seeking to influence.their government; 12L it comments on the process of innovation (3) the inquiry addresses ihe yroblem 6f political development, at least as It exists in urban neighborhoods; and (4)it teeks to lay the groundwork fca theory of neighborhood problem-solving and a strategy of reighborhood development. (Author)JM) ****************44**************************************************** -Documents acquired by EEIC,include many Informal unpublished * materials nct available frOm-other sources. ERIC makes every effort * to obtain.the test copy available. -

John J. Mearsheimer: an Offensive Realist Between Geopolitics and Power

John J. Mearsheimer: an offensive realist between geopolitics and power Peter Toft Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen, Østerfarimagsgade 5, DK 1019 Copenhagen K, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] With a number of controversial publications behind him and not least his book, The Tragedy of Great Power Politics, John J. Mearsheimer has firmly established himself as one of the leading contributors to the realist tradition in the study of international relations since Kenneth Waltz’s Theory of International Politics. Mearsheimer’s main innovation is his theory of ‘offensive realism’ that seeks to re-formulate Kenneth Waltz’s structural realist theory to explain from a struc- tural point of departure the sheer amount of international aggression, which may be hard to reconcile with Waltz’s more defensive realism. In this article, I focus on whether Mearsheimer succeeds in this endeavour. I argue that, despite certain weaknesses, Mearsheimer’s theoretical and empirical work represents an important addition to Waltz’s theory. Mearsheimer’s workis remarkablyclear and consistent and provides compelling answers to why, tragically, aggressive state strategies are a rational answer to life in the international system. Furthermore, Mearsheimer makes important additions to structural alliance theory and offers new important insights into the role of power and geography in world politics. Journal of International Relations and Development (2005) 8, 381–408. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jird.1800065 Keywords: great power politics; international security; John J. Mearsheimer; offensive realism; realism; security studies Introduction Dangerous security competition will inevitably re-emerge in post-Cold War Europe and Asia.1 International institutions cannot produce peace. -

7972-1 Comparative Political Institutions (Clark)

COMPARATIVE POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS Political Science 7972 Prof Wm A Clark Thursdays 9:00-12:00 213 Stubbs Hall 210 Stubbs Hall [email protected] Fall 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is dedicated to the comparative analysis of political institutions, which in comparative politics are viewed as either formal rules or organizations. The primary orientation of the course material lies in state governmental institutions, although some social institutions will also be examined. The course focuses on what has come to be called the "new institutionalism," which adopts a more decidedly structural or state-centric approach to politics. It emphasizes the relative autonomy of political institutions, and thus seeks to present a counterweight to the predominant view of politics as merely a reflection of the aggregation of individual preferences and behaviors. If it can be argued that individuals and institutions impact each other, the new institutionalism focuses primary attention on how relatively autonomous political institutions (i.e., rules and organizations) affect individual political behavior. COURSE REQUIREMENTS Each student’s semester grade will be determined on the basis of four tasks, detailed below. [1] Research paper: weighted at 35% of the course grade. This paper is to be modeled on a typical conference paper. The paper should focus on the downstream consequence(s) of a national or sub-national institutional variable; that is, it should adopt an institutional factor (or factors) as the independent variable(s). It should focus on any country other than the USA, and may adopt any traditional form of institutional analysis. It must be fully cited and written to professional standards. -

"The New Non-Science of Politics: on Turns to History in Polltical Sciencen

"The New Non-Science of Politics: On Turns to History in Polltical Sciencen Rogers Smith CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #59 Paper #449 October 1990 The New Non-Science of Politics : On Turns to Historv in Political Science Prepared for the CSST Conference on "The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences" Oct. 5-7, 1990 Ann Arbor, Michigan Rogers M. Smith Department of Political Science Yale University August, 1990 The New Non-Science of Po1itic.s Rogers M. Smit-h Yale University I. Introducticn. The canon of major writings on politics includes a considerable number that claim to offer a new science of politics, or a new science of man that encompasses politics. Arlc,totle, Hobbos, Hume, Publius, Con~te,Bentham, Hegel, Marx, Spencer, Burgess, Bentley, Truman, East.on, and Riker are amongst the many who have clairr,ed, more or less directly, that they arc founding or helping to found a true palitical science for the first tlme; and the rccent writcrs lean heavily on the tcrni "science. "1 Yet very recently, sorno of us assigned the title "political scien:iSt" havc been ti-il-ning returning to act.ivities that many political scientist.^, among others, regard as unscientific--to the study of instituti~ns, usually in historical perspective, and to historica! ~a'lternsand processes more broadly. Some excellent scholars belie-ve this turn is a disast.er. It has been t.ernlod a "grab bag of diverse, often conf!icting approaches" that does not offer anything iike a scientific theory (~kubband Moe, 1990, p. 565) .2 In this essay I will argue that the turn or return t.o institutions and history is a reasonable response to two linked sets of probicms. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover