The Impact of Font Type on Reading Stephanie Hoffmeister Eastern Michigan University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cloud Fonts in Microsoft Office

APRIL 2019 Guide to Cloud Fonts in Microsoft® Office 365® Cloud fonts are available to Office 365 subscribers on all platforms and devices. Documents that use cloud fonts will render correctly in Office 2019. Embed cloud fonts for use with older versions of Office. Reference article from Microsoft: Cloud fonts in Office DESIGN TO PRESENT Terberg Design, LLC Index MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS A B C D E Legend: Good choice for theme body fonts F G H I J Okay choice for theme body fonts Includes serif typefaces, K L M N O non-lining figures, and those missing italic and/or bold styles P R S T U Present with most older versions of Office, embedding not required V W Symbol fonts Language-specific fonts MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS Abadi NEW ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Abadi Extra Light ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic or bold styles provided. Agency FB MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Agency FB Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Note: No italic style provided Algerian MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ 01234567890 Note: Uppercase only. No other styles provided. Arial MICROSOFT OFFICE CLOUD FONTS ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz 01234567890 Arial Bold Italic ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ -

15 the Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia

The Effect of Font Type on Screen Readability by People with Dyslexia LUZ RELLO and RICARDO BAEZA-YATES, Web Research Group, DTIC, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain Around 10% of the people have dyslexia, a neurological disability that impairs a person’s ability to read and write. There is evidence that the presentation of the text has a significant effect on a text’s accessibility for people with dyslexia. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no experiments that objectively 15 measure the impact of the typeface (font) on screen reading performance. In this article, we present the first experiment that uses eye-tracking to measure the effect of typeface on reading speed. Using a mixed between-within subject design, 97 subjects (48 with dyslexia) read 12 texts with 12 different fonts. Font types have an impact on readability for people with and without dyslexia. For the tested fonts, sans serif , monospaced, and roman font styles significantly improved the reading performance over serif , proportional, and italic fonts. On the basis of our results, we recommend a set of more accessible fonts for people with and without dyslexia. Categories and Subject Descriptors: H.5.2 [Information Interfaces and Presentation]: User Interfaces— Screen design, style guides; K.4.2 [Computers and Society]: Social Issues—Assistive technologies for per- sons with disabilities General Terms: Design, Experimentation, Human Factors Additional Key Words and Phrases: Dyslexia, learning disability, best practices, web accessibility, typeface, font, readability, legibility, eye-tracking ACM Reference Format: Luz Rello and Ricardo Baeza-Yates. 2016. The effect of font type on screen readability by people with Dyslexia. -

1 Warum Hassen Alle Comic Sans?

Preprint von: Meletis, Dimitrios. 2020. Warum hassen alle Comic Sans? Metapragmatische Onlinediskurse zu einer typographischen Hassliebe. In Jannis Androutsopoulos/Florian Busch (eds.), Register des Graphischen: Variation, Praktiken, Reflexion, 253-284. Boston, Berlin: De Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110673241-010. Warum hassen alle Comic Sans? Metapragmatische Onlinediskurse zu einer typographischen Hassliebe Dimitrios Meletis Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz 1. Einleitung If you love it, you don’t know much about typography, and if you hate Com- ic Sans you don’t know very much about typography either, and you should probably get another hobby. Vincent Connare, Designer von Comic Sans1 Spätestens ab dem Zeitpunkt, als mit dem Aufkommen des PCs einer breiten Masse die Möglichkeit geboten wurde, Schriftprodukte mithilfe von vorinstallierten Schriftbear- beitungsprogrammen und darin angebotenen Schriftarten nach Belieben selbst zu gestal- ten, wurde – oftmals unbewusst – mit vielen (vor allem impliziten) Konventionen ge- brochen. Comic Sans kann in diesem Kontext als Paradebeispiel gelten: Die 1994 ent- worfene Type (in Folge simplifiziert: Schriftart, Schrift) wird im Internet vor allem auf- grund von Verwendungen in dafür als unpassend empfundenen Situationen von vielen leidenschaftlich ‚gehasst‘. So existiert(e) unter anderem ein Manifest, das ein Verbot der Schrift fordert(e) (bancomicsans.com).2 Personen, die die „Schauder-Schrift“ (Lischka 2008) „falsch“ verwenden, werden als Comic Sans Criminals bezeichnet und ihnen wird Hilfe angeboten, -

Arab Children's Reading Preference for Different Online Fonts

Arab Children’s Reading Preference for Different Online Fonts Asmaa Alsumait1, Asma Al-Osaimi2, and Hadlaa AlFedaghi2 1 Computer Engineering Dep., Kuwait University, Kuwait 2 Regional Center For Development of Educational Software, Kuwait [email protected], {alosaimi,hadlaa}@redsoft.org Abstract. E-learning education plays an important role in the educational proc- ess in the Arab region. There is more demand to provide Arab students with electronic resources for knowledge now than before. The readability of such electronic resources needs to be taken into consideration. Following design guidelines in the e-learning programs’ design process improves both the reading performance and satisfaction. However, English script design guidelines cannot be directly applied to Arabic script mainly because of difference in the letters occupation and writing direction. Thus, this paper aimed to build a set of design guidelines for Arabic e-learning programs designed for seven-to-nine years old children. An electronic story is designed to achieve this goal. It is used to gather children’s reading preferences, for example, font type/size combination, screen line length, and tutoring sound characters. Results indicated that Arab students preferred the use of Simplified Arabic with 14-point font size to ease and speed the reading process. Further, 2/3 screen line length helped children in reading faster. Finally, most of children preferred to listen to a female adult tutoring sound. Keywords: Child-Computer Interfaces, E-Learning, Font Type/Size, Human- Computer Interaction, Information Interfaces and Presentation, Line Length, Tutoring Sound. 1 Introduction Ministries of education in the Arab region are moving toward adopting e-learning methods in the educational process. -

System Profile

Steve Sample’s Power Mac G5 6/16/08 9:13 AM Hardware: Hardware Overview: Model Name: Power Mac G5 Model Identifier: PowerMac11,2 Processor Name: PowerPC G5 (1.1) Processor Speed: 2.3 GHz Number Of CPUs: 2 L2 Cache (per CPU): 1 MB Memory: 12 GB Bus Speed: 1.15 GHz Boot ROM Version: 5.2.7f1 Serial Number: G86032WBUUZ Network: Built-in Ethernet 1: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en0 IPv4 Addresses: 192.168.1.3 IPv4: Addresses: 192.168.1.3 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en0 NetworkSignature: IPv4.Router=192.168.1.1;IPv4.RouterHardwareAddress=00:0f:b5:5b:8d:a4 Router: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.255.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic DNS: Server Addresses: 192.168.1.1 DHCP Server Responses: Domain Name Servers: 192.168.1.1 Lease Duration (seconds): 0 DHCP Message Type: 0x05 Routers: 192.168.1.1 Server Identifier: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Mask: 255.255.255.0 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: Yes Auto Discovery Enabled: No Ethernet: MAC Address: 00:14:51:67:fa:04 Media Options: Full Duplex, flow-control Media Subtype: 100baseTX Built-in Ethernet 2: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en1 IPv4 Addresses: 169.254.39.164 IPv4: Addresses: 169.254.39.164 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.0.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic AppleTalk: Configuration Method: Node Default Zone: * Interface Name: en1 Network ID: 65460 Node ID: 139 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: -

Loopagroup - Travel Network Logo and Website

Loopagroup - Travel Network Logo and Website By Erica Dang Department of Art & Design College of Liberal Arts Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo March 2009 Abstract This report contains information on working with a client and the internet, designing a travel network’s logo and website look and feel. Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction . 1 Statement of Problem Purpose or Objective of Study Limitations of the Study Chapter 2: Review of Research . 3 Chapter 3: Procedures and Results . 5 Chapter 4: Summary and Recommendations . 26 Bibliography . 28 i Chapter 1 – Introduction Statement of Problem: Level Studios in San Luis Obispo is looking to create a travel network logo and web site. Purpose or Objective of the Study: When it was time to choose a senior project, I examined my portfolio and looked for areas of graphic design that were missing, such as web design. This project will show that I am a well rounded designer. Many companies are now looking for web designers and knowing how the web works is helpful. Limitations of the Study: Some limitations were lack of time, travel issues, conflicting schedules for meetings and consultations, and limited web font selections. For example, most of the meetings took place Monday nights. However, sometimes the clients had to stay late at work and could not make it to some meetings. When there was a Monday holiday, some members of the group were out of town and could not meet. Regarding typography, the client saw all serif fonts fit for the web appeared the same. Common fonts to all versions of Windows and Mac equivalents are: Arial, Arial Black, Helvetica, Gadget, Comic Sans, Courier New, Georgia, Impact, Lucida Console, Lucida Sans Unicode, Lucida Grande, Monaco, Palatino, Book Antiqua, Tahoma, Trebuchet, Verdana, Symbol, and Webdngs. -

Stop Stealing Sheep & Find out How Type Works

1 Stop Stealing Sheep This page intentionally left blank 3 Stop Stealing Sheep & find out how type works Third Edition Erik Spiekermann Stop Stealing Sheep trademarks & find out how type works Adobe, Photoshop, Illustrator, Third Edition PostScript, and CoolType are registered Erik Spiekermann trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or This Adobe Press book is other countries. ClearType is a trade published by Peachpit, mark of Microsoft Corp. All other a division of Pearson Education. trademarks are the property of their respective owners. For the latest on Adobe Press books, go to www.adobepress.com. Many of the designations used by To report errors, please send a note to manufacturers and sellers to dis tinguish [email protected]. their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in Copyright © 2014 by Erik Spiekermann this book, and Peachpit was aware of a trademark claim, the designations appear Acquisitions Editor: Nikki Echler McDonald as requested by the owner of the trade Production Editor: David Van Ness mark. All other product names and Proofer: Emily Wolman services identified throughout this book Indexer: James Minkin are used in editorial fashion only and Cover Design: Erik Spiekermann for the benefit of such companies with no intention of infringement of the notice of rights trademark. No such use, or the use of any All rights reserved. No part of this trade name, is intended to convey book may be reproduced or transmitted endorsement or other affiliation with in any form by any means, electronic, this book. mechanical, photocopying, recor ding, or otherwise, without the prior isbn 13: 9780321934284 written permission of the publisher. -

Fonts Installed with Each Windows OS

FONTS INSTALLED WITH EACH WINDOWS OPERATING SYSTEM WINDOWS95 WINDOWS98 WINDOWS2000 WINDOWSXP WINDOWSVista WINDOWS7 Fonts New Fonts New Fonts New Fonts New Fonts New Fonts Arial Abadi MT Condensed Light Comic Sans MS Estrangelo Edessa Cambria Gabriola Arial Bold Aharoni Bold Comic Sans MS Bold Franklin Gothic Medium Calibri Segoe Print Arial Bold Italic Arial Black Georgia Franklin Gothic Med. Italic Candara Segoe Print Bold Georgia Bold Arial Italic Book Antiqua Gautami Consolas Segoe Script Georgia Bold Italic Courier Calisto MT Kartika Constantina Segoe Script Bold Georgia Italic Courier New Century Gothic Impact Latha Corbel Segoe UI Light Courier New Bold Century Gothic Bold Mangal Lucida Console Nyala Segoe UI Semibold Courier New Bold Italic Century Gothic Bold Italic Microsoft Sans Serif Lucida Sans Demibold Segoe UI Segoe UI Symbol Courier New Italic Century Gothic Italic Palatino Linotype Lucida Sans Demibold Italic Modern Comic San MS Palatino Linotype Bold Lucida Sans Unicode MS Sans Serif Comic San MS Bold Palatino Linotype Bld Italic Modern MS Serif Copperplate Gothic Bold Palatino Linotype Italic Mv Boli Roman Small Fonts Copperplate Gothic Light Plantagenet Cherokee Script Symbol Impact Raavi NOTE: Trebuchet MS The new Vista fonts are the Times New Roman Lucida Console Trebuchet MS Bold Script newer cleartype format Times New Roman Bold Lucida Handwriting Italic Trebuchet MS Bold Italic Shruti designed for the new Vista Times New Roman Italic Lucida Sans Italic Trebuchet MS Italic Sylfaen display technology. Microsoft Times -

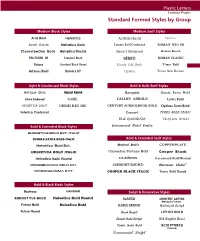

Standard Formed Styles by Group

Plastic Letters Formed Plastic Standard Formed Styles by Group Medium Block Styles Medium Serif Styles Arial Bold Helvetica Architectural Palatino Avant Garde Helvetica Italic Century Bold Condensed ROMAN NEO SB ClearviewOne Bold Helvetica Round Consort Condensed Roman Round FRUTIGER 65 Standard Block gemco ROMAN CLASSIC Futura Standard Block Round Goudy Old Style Times Bold Gil Sans Bold Univers 67 Optima Times New Roman Light & Condensed Block Styles Bold & Italic Serif Styles Antique Olive Impact Round Benguiat Goudy Extra Bold Futura Condensed KABEL CASLON ADBOLD Lotus Bold HELVETICA LIGHT standard block cond. CENTURY SCHOOLBOOK BOLD Optima Semi Bold Helvetica Condensed Consort TIMES BOLD ITALIC FRIZ QUADRATA TRAJAN BOLD Bold & Extended Block Styles Garamond Bold Italic EUROSTYLE BOLD EXT. ITALIC FUTURA EXTRA BOLD ITALIC Bold & Extended Serif Styles Helvetica Bold Ext. Bodoni Italic COPPERPLATE HELVETICA BOLD ITALIC Clarendon Fortune Bold Cooper Black Helvetica Italic Round clarion G a r a m ond B ol d R ou nd ® MICROGRAMMA BOLD EXT. CONSORT ROUND Herman Italic MICROGRAMMA EXT. COOPER BLACK ITALIC Times Bold Round Bold & Black Block Styles Bauhaus HARRIER Script & Decorative Styles EUROSTYLE BOLD Helvetica Bold Round BARNUM COUNTRY GOTHIC (Woodgrain Texture) Futura Bold Helvetica Bold CLASSIC BARNUM Italicized Script Futura Round Brush Script LITHOS BOLD Casual Italic Script Old English Bevel Comic Sans Bold SCULPTURED (Textured) Commercial Script Plastic Letters Formed Plastic MEDICAL SYMBOLS HEIGHT WIDTH DEPTH 12” 10” 1” 15 12 1 1/4 Staff of Asclepius Chiropractic Veterinary Symbol of Life 18 14 1 1/2 24 18 2 The Staff of Asclepius is the officially recognized medical DDS OD symbol of the American Medical Association. -

Contemporary Processes of Text Typeface Design

Title Contemporary processes of text typeface design Type The sis URL https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/13455/ Dat e 2 0 1 8 Citation Harkins, Michael (2018) Contemporary processes of text typeface design. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Cr e a to rs Harkins, Michael Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected] . License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Contemporary processes of text typeface design Michael Harkins Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Central Saint Martins University of the Arts London April 2018 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my brother, Lee Anthony Harkins 22.01.17† and my father, Michael Harkins 11.04.17† Abstract Abstract Text typeface design can often be a lengthy and solitary endeavour on the part of the designer. An endeavour for which, there is little in terms of guidance to draw upon regarding the design processes involved. This is not only a contemporary problem but also an historical one. Examination of extant accounts that reference text typeface design aided the orientation of this research (Literature Review 2.0). This identified the lack of documented knowledge specific to the design processes involved. Identifying expert and non-expert/emic and etic (Pike 1967) perspectives within the existing literature helped account for such paucity. In relation to this, the main research question developed is: Can knowledge of text typeface design process be revealed, and if so can this be explicated theoretically? A qualitative, Grounded Theory Methodology (Glaser & Strauss 1967) was adopted (Methodology 3.0), appropriate where often a ‘topic of interest has been relatively ignored in the literature’ (Goulding 2002, p.55). -

Christoph Knoth PB Computed Type Design

COMPUTED TYPE DESIGN Christoph Knoth PB Computed Type Design A Abstract A lot of tasks in font design are interlinked and a change on one Is it possible to create a far more easy to use program to letter will maybe create hours of work on others. The idea of a design western characters by trying to analyze the strongness parametrical typeface could minimize those problems and would and weakness of other approaches? And does a programmatic allow to design an infinite number of typefaces at the same approach to type design help to create new and interesting time. curves and shapes for letterforms something that would not • I will try to understand why this way of designing a font have been imagined before? never got widely adopted. If it is possible to create a more easy to use program to design western characters. And finally if this approach to type design would help to create new and interesting curves and shapes for letterforms. C History To understand how type design works today one has to B Introduction understand the history of type design. That is why I have collected some early historical samples that show first approaches for a mathematical notation and a systematical Type design is a long and tedious process. Just to design modification and variation of fonts in a pre computer era. the basic letters takes days and it sometimes takes years for • Followed by a short chapter about the curve and another a full character set. The process has changed over time with chapter where I will try to shed some light on the changes that technology evolving giving the designer more and more the computer brought to the type design industry. -

The Influence of Typeface on Students' Perceptions of Online Instructors

Information Systems Education Journal (ISEDJ) 12 (3) ISSN: 1545-679X May 2014 The Influence of Typeface on Students’ Perceptions of Online Instructors Michelle O’Brien Louch [email protected] Duquesne University Elizabeth Stork [email protected] Robert Morris University Abstract At its base, advertising is the process of using visual images and words to attract and convince consumers that a certain product has certain attributes. The same effect exists in electronic communication, strongly so in online courses where most if not all interaction between instructor and student is in writing. Arguably, if consumers make certain assumptions about a product based on the typeface used on a package, then online students are poised to do the same when they read emails from an online instructor. This pilot study looked at the specific medium of e-mail and how an e- mail’s recipient (student) might transfer his or her perceptions of attributes of three typefaces to attributes of the sender (instructor) of the email. One was a commonly used typeface, and the other two were selected for their dramatic differences from the common typeface. The findings revealed that the participants’ opinions of the sender were highly influenced by the typeface used. In the arena of online education, attention should be given to typeface selection in instructors’ emails to students. Keywords: Typeface, Online Education, Email, Communication, Font, Teacher-student Interaction 1. INTRODUCTION a page simplifies and ultimately limits the message. Readers “design multiple Consider the act of reading body language. One interconnections” between what they see and watches and listens, giving meaning to both the what they read (Lemke, 2009, p.