Growth and Development in South Africa's Heartland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Policy and Mine Closure in South Africa: the Case of the Free State Goldfields

Resources Policy 38 (2013) 363–372 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol Resources policy and mine closure in South Africa: The case of the Free State Goldfields Lochner Marais n Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa article info abstract Article history: There is increasing international pressure to ensure that mining development is aligned with local and Received 24 October 2012 national development objectives. In South Africa, legislation requires mining companies to produce Received in revised form Social and Labour Plans, which are aimed at addressing local developmental concerns. Against the 25 April 2013 background of the new mining legislation in South Africa, this paper evaluates attempts to address mine Accepted 25 April 2013 downscaling in the Free State Goldfields over the past two decades. The analysis shows that despite an Available online 16 July 2013 improved legislative environment, the outcomes in respect of integrated planning are disappointing, Keywords: owing mainly to a lack of trust and government incapacity to enact the new legislation. It is argued that Mining legislative changes and a national response in respect of mine downscaling are required. Communities & 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Mine closure Mine downscaling Local economic development Free State Goldfields Introduction areas were also addressed. According to the new Act, mining companies are required to provide, inter alia, a Social and Labour For more than 100 years, South Africa's mining industry has Plan as a prerequisite for obtaining mining rights. These Social and been the most productive on the continent. -

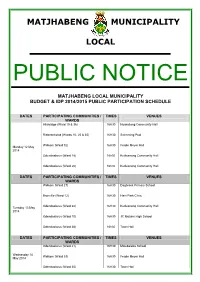

Matjhabeng Municipality Local

MATJHABENG MUNICIPALITY LOCAL PUBLIC NOTICE MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BUDGET & IDP 2014/2015 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SCHEDULE DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Allanridge (Ward 19 & 36) 16H30 Nyakallong Community Hall Riebeeckstad (Wards 10, 25 & 35) 16H30 Swimming Pool Welkom (Ward 32) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall Monday 12 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 18) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Odendaalsrus (Ward 20) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Welkom (Ward 27) 16H30 Dagbreek Primary School Bronville (Ward 12) 16H30 Hani Park Clinic Odendaalsrus (Ward 22) 16H30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Tuesday 13 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 10) 16H30 JC Motumi High School Odendaalsrus (Ward 36) 16h30 Town Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Odendaalsrus (Ward 21) 16H30 Malebaleba School Wednesday 14 Welkom (Ward 33) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 35) 16H30 Town Hall Bronville (Ward 11) 16H30 Bronville Community Hall Welkom (Ward 24) 16H30 Reahola Housing Units DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Bronville (Ward 23) 16H30 Hani Park Church Thabong (Ward 12) 16H30 Tsakani School Thursday 15 May Thabong (Ward 30) 16H30 Thabong Primary School 2014 Thabong (Ward 31) 16H30 Thabong Community Centre Thabong (Ward 28) 16H30 Thembekile School DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Thabong (Ward 26) 16H30 Bofihla School Thabong (Ward 29) 16H30 Lebogang School Monday 19 May 2014 Thabong Far East (Ward 25) 16H30 Matshebo School -

General Observations About the Free State Provincial Government

A Better Life for All? Fifteen Year Review of the Free State Provincial Government Prepared for the Free State Provincial Government by the Democracy and Governance Programme (D&G) of the Human Sciences Research Council. Ivor Chipkin Joseph M Kivilu Peliwe Mnguni Geoffrey Modisha Vino Naidoo Mcebisi Ndletyana Susan Sedumedi Table of Contents General Observations about the Free State Provincial Government........................................4 Methodological Approach..........................................................................................................9 Research Limitations..........................................................................................................10 Generic Methodological Observations...............................................................................10 Understanding of the Mandate...........................................................................................10 Social attitudes survey............................................................................................................12 Sampling............................................................................................................................12 Development of Questionnaire...........................................................................................12 Data collection....................................................................................................................12 Description of the realised sample.....................................................................................12 -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

Uys Van Heerden

FREE DECEMBER 2016 • JANUARY 2017 SENWES EQUIPMENT AND JOHN DEERE’S GATOR WINNER Senwes Equipment and JCB – A perfect match Win with Nation in Conversation FOCUS ON Welkom & Odendaalsrus An introduction to OneAgri CHRISTMAS PERFORMANCE AND PRODUCTIVITY. SPECIAL OFFERS REDUCED RATES POSTPONED INSTALMENTS *Terms and conditions apply My choice, my Senwes. At Senwes Equipment we know what our clients want and we make sure that they get it. As the exclusive John Deere dealer we guarantee your access to the latest developments. PLEASEWe ensure CONTACTthat you have YOUR the best that money has to oer. NEAREST SENWES EQUIPMENT BRANCH FOR MORE INFO. CONTENTS ••••••• 8 31 4 CONTENTS EDITOR'S LETTER 20 Management of variables in a 2 It is raining! farming system with the assistance ON THE COVER PAGE of precision farming WHAT A YEAR 2016 has been for GENERAL 23 Meet Estelle ‘Senwes’ the newly established trademark of 3 Cartoon: Pieter & Tshepo 25 Herman is your Senwes Man – Senwes Equipment! With prize upon 3 Heard all over A grain marketing advisor with the prize they really created a Christmas 15 Christmas messages full package spirit. 26 How the handling of grain On the front page we have Gert MAIN ARTICLE changed over time? Part I 4 JCB and Senwes Equipment: A (Gerlu) Roos from Wonderfontein, 28 Branch manager Potchefstroom who won the second leg of the WIN perfect match! – Ruan brings colour to Potch BIG with Senwes Equipment and John Deere competition in Novem- 30 Utilise our Digital Platforms AREA FOCUS ber. In the process he won a John in an optimal manner 8 Welkom and Odendaalsrus Deere Gator 855D to the value of – In Circles! 46 Gert Roos wins R230 000 John R230 000, a wonderful gift, just in Deere Gator 855D time for Christmas. -

WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association

ACLA 2017 ACLA WELKOM Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association ACLA 2017 | Utrecht University TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome and Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................4 Welcome from Utrecht Mayor’s Office .....................................................................................6 General Information ................................................................................................................... 7 Conference Schedule ................................................................................................................. 14 Biographies of Keynote Speakers ............................................................................................ 18 Film Screening, Video Installation and VR Poetry ............................................................... 19 Pre-Conference Workshops ...................................................................................................... 21 Stream Listings ..........................................................................................................................26 Seminars in Detail (Stream A, B, C, and Split Stream) ........................................................42 Index......................................................................................................................................... 228 CFP ACLA 2018 Announcement ...........................................................................................253 Maps -

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve

SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve South Africa AFRICA & ASIA PACIFIC | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Season: 2021 Adult-Exclusive 10 DAYS 23 MEALS 18 SITES Experience the beauty of the people, cultures and landscapes of South Africa on this amazing Adventures by Disney vacation where you’ll thrill to the majesty of seeing wild animals in their natural environments, view Cape Town from atop the awe-inspiring Table Mountain and travel to the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of the continent. SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve Trip Overview 10 DAYS / 9 NIGHTS ACCOMMODATIONS 3 LOCATIONS Table Bay Hotel Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Pezula Hotel Game Reserve Kapama River Lodge AGES FLIGHT INFORMATION 23 MEALS Minimum Age: 6 Arrive: Cape Town (CPT) 9 Breakfasts, 8 Lunches, 6 Suggested Age: 8+ Return: Johannesburg (JNB) Dinners Adult Exclusive: Ages 18+ 3 Internal Flights Included SOUTH AFRICA Africa & Asia Pacific | Cape Town, Knysna, Kapama Game Reserve DAY 1 CAPE TOWN Activities Highlights: No Meals Included Arrive in Cape Town Table Bay Hotel Arrive at Cape Town Welkom! Upon exiting customs, be greeted by an Adventures by Disney representative who escorts you to your transfer vehicle. Relax as the driver assists with your luggage and takes you to the Table Bay Hotel. Table Bay Hotel Unwind from your journey as your Adventure Guide checks you into this spacious, sophisticated, full-service hotel located on the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront. Ask your Adventure Guide for suggestions about exploring Cape Town on your own. -

Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg

CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT SENTRUM VIR ONTWIKKELINGSTEUN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lead authors: Lochner Marais (University of the Free State) Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Case study authors: Drakenstein: Ronnie Donaldson (Stellenbosch University) King Sabata Dalindyebo: Esethu Ndzamela (Nelson Mandela University) and Anton De Wit (Nelson Mandela University Lephalale: Kgosi Mocwagae (University of the Free State) Matjhabeng: Stuart Denoon-Stevens (University of the Free State) Mahikeng: Verna Nel (University of the Free State) and James Drummond (North West University) Mbombela: Maléne Campbell (University of the Free State) Msunduzi: Thuli Mphambukeli (University of the Free State) Polokwane: Gemey Abrahams (independent consultant) Rustenburg: John Ntema (University of South Africa) Sol Plaatje: Thomas Stewart (University of the Free State) Stellenbosch: Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Manager: Geci Karuri-Sebina Editing by Write to the Point Design by Ink Design Photo Credits: Page 2: JDA/SACN Page 16: Edna Peres/SACN Pages 18, 45, 47, 57, 58: Steve Karallis/JDA/SACN Page 44: JDA/SACN Page 48: Tanya Zack/SACN Page 64: JDA/SACN Suggested citation: SACN. 2017. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg. Available online at www.sacities.net ISBN: 978-0-6399131-0-0 © 2017 by South African Cities Network. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. 2 SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: ARE INTERMEDIATE CITIES DIFFERENT? Foreword As a network whose primary stakeholders are the largest cities, the South African Cities Network (SACN) typically focuses its activities on the “big” end of the urban spectrum (essentially, mainly the metropolitan municipalities). -

Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Published by the Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), the African Centre for Cities (ACC) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Southern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2, Canada African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa International Development Research Centre, 160 Kent St, Ottawa, Canada K1P 0B2 and Eaton Place, 3rd floor, United Nations Crescent, Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya ISBN 978-1-920596-11-8 © SAMP 2015 First published 2015 Production, including editing, design and layout, by Bronwen Dachs Muller Cover by Michiel Botha Cover photograph by Alon Skuy/The Times. The photograph shows Soweto residents looting a migrant-owned shop in a January 2015 spate of attacks in South Africa Index by Ethné Clarke Printed by MegaDigital, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Edited by Jonathan Crush Abel Chikanda Caroline Skinner Acknowledgements The editors would like to acknowledge the financial and programming support of the Inter- national Development Research Centre (IDRC), which funded the research of the Growing Informal Cities Project and the Workshop on Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepre- neurship in Southern African Cities hosted by SAMP and the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town in February 2014. Many of the chapters in this volume were first presented at this workshop. -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

1 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA DATE: 2013-10-17 REPORT TO: ADEL GROENEWALD (Enviroworks) Tel: 086 198 8895; Fax: 086 719 7191; Postal Address: Suite 116, Private Bag X01, Brandhof, 9301; E-mail: [email protected] ANDREW SALOMON (South African Heritage Resources Agency - SAHRA) Tel: 021 462 4505; Fax: 021 462 4509; Postal Address: P.O. Box 4637, Cape Town, 8000; E-mail: [email protected] PREPARED BY: KAREN VAN RYNEVELD (ArchaeoMaps) Tel: 084 871 1064; Fax: 086 515 6848; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205; E-mail: [email protected] THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 2 SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INTEREST I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, ’ proponent or any subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted has been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. SIGNATURE – DATE – 2013-10-17 THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 3 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TERMS OF REFERENCE - Enviroworks has been appointed by the project proponent, Lebone Solar Farm (Pty) Ltd, to prepare and submit the EIA and EMPr for the proposed 75MW photovoltaic (PV) solar facility on the properties Remaining Extent of Farm Onverwag 728 and Portion 2 of Farm Vaalkranz 220 near Welkom in the Free State, South Africa. -

Ventersburg Consolidated Prospecting Right Project

VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Submitted in support of the Prospecting Right and Environmental Authorisation Application Prepared on Behalf of: WESTERN ALLEN RIDGE GOLD MINES (PTY) LTD (Subsidiary of White Rivers Exploration (Pty) Ltd) DMR REFERENCE NUMBER: FS 30/5/1/1/3/2/1/1/10489 EM 18 APRIL 2018 Dunrose Trading 186 (PTY) Ltd T/A Shango Solutions Registration Number: 2004/003803/07 H.H.K. House, Cnr Ethel Ave and Ruth Crescent, Northcliff Tel: +27 (0)11 678 6504, Fax: +27 (0)11 678 9731 VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Compiled by: Ms Nangamso Zizo Siwendu Environmental Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 072 669 6250 E-mail: [email protected] Reviewed by: Dr Jochen Schweitzer Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 082 448 2303 E-mail: [email protected] Ms Stefanie Weise Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 081 549 5009 E-mail: [email protected] DOCUMENT CONTROL Revision Date Report 1 12 March 2018 Draft Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme 2 18 April 2018 Final Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme DISCLAIMER AND TERMS OF USE This report has been prepared by Dunrose Trading 186 (Pty) Ltd t/a Shango Solutions using information provided by its client as well as third parties, which information has been presumed to be correct. Shango Solutions does not accept any liability for any loss or damage which may directly or indirectly result from any advice, opinion, information, representation or omission, whether negligent or otherwise, contained in this report.