10. Chapter 3 Transformation from Naples to Ferrara 139–186

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... The Civic Virtue of Women in Quattrocento Florence A Dissertation Presented by Christine Contrada to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Christine Contrada 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Christine Contrada We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dr. Alix Cooper – Dissertation Advisor Associate Professor, History Dr. Joel Rosenthal – Chairperson of Defense Distinguished Professor Emeritus, History Dr. Gary Marker Professor, History Dr. James Blakeley Assistant Professor, History St. Joseph’s College, New York This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School. Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation The Civic Virtue of Women in Quattrocento Florence by Christine Contrada Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 Fifteenth century Florence has long been viewed as the epicenter of Renaissance civilization and a cradle of civic humanism. This dissertation seeks to challenge the argument that the cardinal virtues, as described by humanists like Leonardo Bruni and Matteo Palmieri, were models of behavior that only men adhered to. Elite men and women alike embraced the same civic ideals of prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. Although they were not feminists advocating for social changes, women like Alessandra Strozzi, Margherita Datini, and Lucrezia Tornabuoni had a great deal of opportunity to actively support their own interests and the interests of their kin within popular cultural models of civic virtue. -

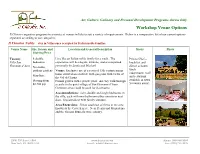

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

Papst Und Kardinalskolleg Im Bannkreis Der Konzilien – Von Der Wahl Martins V

Sonderdrucke aus der Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg JÜRGEN DENDORFER / CLAUDIA MÄRTL Papst und Kardinalskolleg im Bannkreis der Konzilien – von der Wahl Martins V. bis zum Tod Pauls II. (1417-1471) Originalbeitrag erschienen in: Jürden Dendorfer/Ralf Lützelschwab (Hrsg.): Geschichte des Kardinalats im Mittelalter (Päpste und Papsttum 39). Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 2011, S. 335-397. Papst und Kardinalskolleg im Bannkreis der Konzilien – von der Wahl Martins V. bis zum Tod Pauls II. (1417–1471) von Jürgen Dendorfer / Claudia Märtl Mit der Wahl Kardinal Oddo Colonnas zu Papst Martin V. auf dem Konstanzer Konzil endete im Jahr 1417 die Kirchenspaltung1. Es begann ein neuer Abschnitt in der Geschichte des Papsttums, den die kirchengeschichtliche Forschung mit dem Schlagwort «Restauration» gekennzeichnet hat. Der mühsame Weg zur Wiederge- winnung des Kirchenstaats nach den Entwicklungen der avignonesischen Zeit, vor allem aber der Anspruch, das Papsttum und die Kurie wieder als unangefochtenen Bezugspunkt einer geeinten Kirche zu etablieren, prägen die nachfolgenden Jahr- zehnte. Dieser Prozess der erneuerten Durchsetzung päpstlicher Autorität vollzog sich in spannungsreicher Auseinandersetzung mit korporativ-konziliaren Vorstellun- gen und Praktiken der Kirchenleitung. Die Konzilien von Konstanz, Pavia-Siena und Basel debattierten zum einen grundsätzlich über das Verhältnis von konzi- liarer und päpstlicher Gewalt (potestas), entwickelten zum anderen aber auch Vor- stellungen von der Verfasstheit der Kirche neben und unter dem Papst, die -

Borso D'este, Venice, and Pope Paul II

I quaderni del m.æ.s. – XVIII / 2020 «Bon fiol di questo stado» Borso d’Este, Venice, and pope Paul II: explaining success in Renaissance Italian politics Richard M. Tristano Abstract: Despite Giuseppe Pardi’s judgment that Borso d’Este lacked the ability to connect single parts of statecraft into a stable foundation, this study suggests that Borso conducted a coherent and successful foreign policy of peace, heightened prestige, and greater freedom to dispose. As a result, he was an active participant in the Quattrocento state system (Grande Politico Quadro) solidified by the Peace of Lodi (1454), and one of the most successful rulers of a smaller principality among stronger competitive states. He conducted his foreign policy based on four foundational principles. The first was stability. Borso anchored his statecraft by aligning Ferrara with Venice and the papacy. The second was display or the politics of splendor. The third was development of stored knowledge, based on the reputation and antiquity of Estense rule, both worldly and religious. The fourth was the politics of personality, based on Borso’s affability, popularity, and other virtues. The culmination of Borso’s successful statecraft was his investiture as Duke of Ferrara by Pope Paul II. His success contrasted with the disaster of the War of Ferrara, when Ercole I abandoned Borso’s formula for rule. Ultimately, the memory of Borso’s successful reputation was preserved for more than a century. Borso d’Este; Ferrara; Foreign policy; Venice; Pope Paul II ISSN 2533-2325 doi: 10.6092/issn.2533-2325/11827 I quaderni del m.æ.s. -

Download (10MB)

AVVERTENZA 11 lavoro, nato come inventario di un « fondo » dell Archivio di Stato geno vese a fini essenzialmente archivistici e non storici, risente di questa sua origine nella rigorosa limitazione dei regesti a quel fondo, pur ricostruito sulla base dell’ordine cronologico dei documenti, e nella sobrietà discreta dei singoli re gesti. Del pari la bibliografia non vuol essere un repertorio critico e non intende richiamare tutte le edizioni comunque eseguite dei diversi atti, ma limita i riferim enti alle edizioni principali, apparse nelle raccolte sistematiche più comu nem ente accessibili, ed a quanto fu pubblicalo del codice diplomatico dell Im periale. Si è ritenuta peraltro utile anche una serie di riferimenti agli Annali di Caffaro e Continuatori per i passi in cui si ricordano i fatti significati dai docum enti del fondo. Il lettore d’altra parte facilmente rileverà che tale appa rato si riferisce con larga prevalenza ai secoli del Medio Evo; il che rappresenta un fatto pieno di significato, anche se la serie dei richiami, come si è detto, e largamente incompleta. Gli indici, alla cui redazione ha direttamente collaborato, col dott. Liscian- drelli ed il dott. Costamagna, anche il Segretario prof. T.O. De Negri, che ha cu rato l’edizione, si riferiscono strettamente ai nomi riportati nei Regesti, ove spesso, per ovvie ragioni, i nominativi personali sono suppliti da richiami anoni mi o da titoli generici (re, pontefice1, imperatore...). Essi hanno quindi un valore indicativo di massima e non possono esaurire la serie dei riferimenti. Per m aggior chiarezza diamo di seguito, col richiamo alle sigle e nell or dine alfabetico delle sigle stesse, l’elenco delle pubblicazioni utilizzate. -

11 the Ciompi Revolt of 1378

The Ciompi Revolt of 1378: Socio-Political Constraints and Economic Demands of Workers in Renaissance Florence Alex Kitchel I. Introduction In June of 1378, political tensions between the Parte Guelpha (supporters of the Papacy) and the Ghibellines (supporters of the Holy Roman Emperor) were on the rise in Italy. These tensions stemmed from the Parte Guelpha’s use of proscriptions (either a death sentence or banishment/exile) and admonitions (denying one’s eligibility for magisterial office) to rid Ghibellines (and whomever else they wanted for whatever reasons) from participation in the government. However, the Guelphs had been unable to prevent their Ghibelline adversary, Salvestro de’ Medici, from obtaining the position of Gonfaloniere (“Standard-Bearer of Justice”), the most powerful position in the commune. By proposing an ultimately unsuccessful renewal of the anti-magnate Law of Ordinances, he was able to win the support of the popolo minuto (“little people”), who, at his bidding, ran around the city, burning and looting the houses of the Guelphs. By targeting specific families and also by allying themselves with the minor guilds, these “working poor” hoped to force negotiations for socio-economic and political reform upon the major-guildsmen. Instead, however, this forced the creation of a balìa (an oligarchic ruling committee of patricians), charged with suppressing the rioting throughout the city. With the city still high-strung, yet more rioting broke out in the following month. The few days before July 21, 1378 were shrouded in conspiracy and plotting. Fearing that the popolo minuto were holding secret meetings all throughout the city, the government arrested some of their leaders, and, under torture, these “little people” confessed to plans of creating three new guilds and eliminating forced loan policies. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

EUI Working Papers

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION EUI Working Papers HEC 2010/02 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE , FLORENCE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION Moving Elites: Women and Cultural Transfers in the European Court System Proceedings of an International Workshop (Florence, 12-13 December 2008) Edited by Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot EUI W orking Paper HEC 2010/02 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1725-6720 © 2010 Giulia Calvi and Isabelle Chabot (eds) Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract The overall evaluation of the formation of political decision-making processes in the early modern period is being transformed by enriching our understanding of political language. This broader picture of court politics and diplomatic networks – which also relied on familial and kin ties – provides a way of studying the political role of women in early modern Europe. This role has to be studied taking into account the overlapping of familial and political concerns, where the intersection of women as mediators and coordinators of extended networks is a central feature of European societies. -

HISTORY ·Op the POPES

THE HISTORY ·op THE POPES, FROM THE CLOSE OF THE MIDDLE AGES . DRAWN FROM THE SECRET ARCHIVES OF THE VATICAN AND O,THER ORIGINAL SOURCES. FROM TH~ GERMAN OF DR . LUDWIG PASTOR, PROFESSOR OF HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF lNNSBRUCJt. IDITFI\ BY FREDERICK IGNATIUS ANTROBUS OF THE ORATORY. FIFTH. EDITION. VOLUME iV. LONDON ROUTLEDGE & KEGAN PAUL LTD BROADWAY HO USE: 6&-74 CARTER.LANE, E.C+ ST. LOUIS, MO.: B. HERDER BOOK CO. 15 & 17 SOUTH ' BRO~WA-Y°: : - 1949 ·. "i . .. .. · .. ' .i:.. : :. '. : •.: .. i.,_, ' : '. , . I '. ' (. • JI . :. .. :! '... ·. ;. ~ .: • • ,J J II ...... I I) ••• .! ~· .! ' • . ·:: . : . ' . ·.... : . " :~ . ' - . • •I ... HIS.TORY OF THE· POPES. VOL. IV. CONTENTS OF VOL. IV. PAGE Table of Contents vii-xxii List of Unpublished Docume1ns in Appendix , xxiii-xxv BOOK I. PAUt. II., l464-1471. Election of 'Paul II. .. 3-35 Paul Ii. and the Renaissance 36-78 The War against the Turks . .. '79-91 Europ~n Policy of Paul 11.-Reforms 92-118 The New Cardinals. The Church Questions in Bohemia 119-147 Paul 11.'s·care for the States of the Church 148-173 Death of Paul II. · 174- 194 . BOOK II. S1xros IV., 1471-1484. Election of Sixtus IV. Rise of the Rovere and Riario families . 231-255 The King of Denmark in Rome . 256-272 The Jubilee "X ear 273-287 Beginning of the Rupture with Lorenzo de' Medici 288-299 The Conspiracy of the Pazzi 300-3rz The Tuscan War 313-330 The Turkish War 331-347 A\lia.nce between the Pope and Venice . 348- 371 The Pope's Struggle with Venice. Death of Sixtus IV. -

9. Chapter 2 Negotiation the Wedding in Naples 96–137 DB2622012

Chapter 2 Negotiation: The Wedding in Naples On 1 November 1472, at the Castelnuovo in Naples, the contract for the marriage per verba de presenti of Eleonora d’Aragona and Ercole d’Este was signed on their behalf by Ferrante and Ugolotto Facino.1 The bride and groom’s agreement to the marriage had already been received by the bishop of Aversa, Ferrante’s chaplain, Pietro Brusca, and discussions had also begun to determine the size of the bride’s dowry and the provisions for her new household in Ferrara, although these arrangements would only be finalised when Ercole’s brother, Sigismondo, arrived in Naples for the proxy marriage on 16 May 1473. In this chapter I will use a collection of diplomatic documents in the Estense archive in Modena to follow the progress of the marriage negotiations in Naples, from the arrival of Facino in August 1472 with a mandate from Ercole to arrange a marriage with Eleonora, until the moment when Sigismondo d’Este slipped his brother’s ring onto the bride’s finger. Among these documents are Facino’s reports of his tortuous dealings with Ferrante’s team of negotiators and the acrimonious letters in which Diomede Carafa, acting on Ferrante’s behalf, demanded certain minimum standards for Eleonora’s household in Ferrara. It is an added bonus that these letters, together with a small collection of what may only loosely be referred to as love letters from Ercole to his bride, give occasional glimpses of Eleonora as a real person, by no means a 1 A marriage per verba de presenti implied that the couple were actually man and wife from that time on.