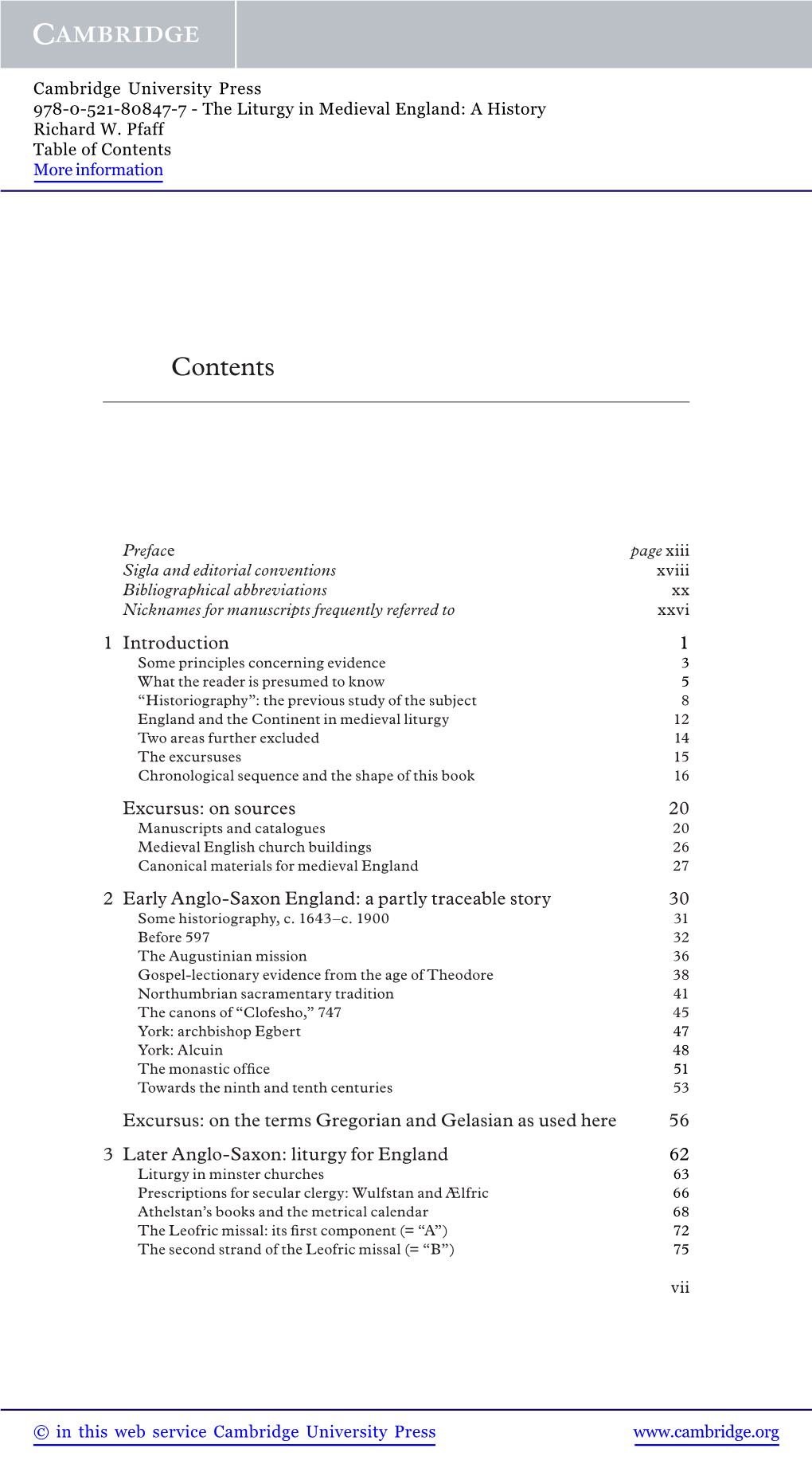

Contents More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Key to the Family Deed Chest How to Decipher and Study Old Documents Being a Guide to the Reading of Ancient Manuscripts E

HOW TO DECIP HER AND STUDY OLD D M E OCU NTS. TH E KE Y TO TH E FA M IL Y D EED CH E S T HOW TO DECIPHER AN D STUDY O LD DO CUMENTS B EING A G UIDE TO TH E READING OF ANCIENT M AN USCRIP TS T T . H Y S E . E O M R H A TENVI LLE ( S. J OHN U COPE) WITH AN INTROD UCTION B Y R E M ART IN C . T I C A Sb ISTA NT K EEP ER O F H M . RE CO R DS SECOND EDITION LONDON I T 6 2 PATERN STER R OW ELL OT S OCK, , O l 9 0 3 P REFAC E TO T H E S ECO ND E D IT I N O . UST ten years ago this little volume made its bo o ks J first appearance . Although many on similar subjects have been written in that time , none have exactly given the same informa tion , and this sec ond edition has been decided n upon . Additions and corrections to bri g the book up to date have been made , but much still an d remains , must remain , imperfect in so small a work on so large a subject, and the present pages only profess to help beginners over some of f the initial di ficulties they will meet with . It has been urged that handwriting and its characteristics have nothing to do with old deeds, but careful study of every line and letter is useful , especially with regard to private letters , or when any question arises as to whether the manuscripts are genuine or forgeries . -

Parish' and 'City' -- a Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440-1600

Early Theatre 6.1(2003) audrey douglas ‘Parish’ and ‘City’ – A Shifting Identity: Salisbury 1440–1600 The study and documentation of ceremony and ritual, a broad concern of Records of Early English Drama, has stimulated discussion about their purpose and function in an urban context. Briefly, in academic estimation their role is largely positive, both in shaping civic consciousness and in harmonizing diverse classes and interests while – as a convenient corollary – simultaneously con- firming local hierarchies. Profitable self-promotion is also part of this urban picture, since ceremony and entertainment, like seasonal fairs, potentially attracted interest from outside the immediate locality. There are, however, factors that compromise this overall picture of useful urban concord: the dominance of an urban elite, for instance, may effectually be stabilized, promoted, or even disguised by ceremony and ritual; on the other hand, margi- nalized groups (women and the poor) have normally no place in them at all.l Those excluded from participation in civic ritual and ceremonial might, nevertheless, be to some extent accommodated in the pre-Reformation infra- structure of trade guilds and religious guilds. Both organizational groups crossed social and economic boundaries to draw male and female members together in ritual and public expression of a common purpose and brotherhood – signalling again (in customary obit, procession, and feasting) harmony and exclusivity, themes with which, it seems, pre-Reformation urban life was preoccupied. But although women were welcome within guild ranks, office was normally denied them. Fifteenth-century religious guilds also saw a decline in membership drawn from the poorer members of society, with an overall tendency for a dominant guild to become identified with a governing urban elite.2 Less obvious perhaps, but of prime importance to those excluded from any of the above, was the parish church itself, whose round of worship afforded forms of ritual open to all. -

Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C

Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C. Corlette Bell's Cathedrals: Chichester (1901) by Hubert C. Corlette Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Victoria Woosley and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. [Illustration: CHICHESTER CATHEDRAL FROM THE SOUTH.] THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF CHICHESTER A SHORT HISTORY & DESCRIPTION OF ITS FABRIC WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE DIOCESE AND SEE HUBERT C. CORLETTE A.R.I.B.A. WITH XLV ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON GEORGE BELL & SONS 1901 page 1 / 148 PREFACE. All the facts of the following history were supplied to me by many authorities. To a number of these, references are given in the text. But I wish to acknowledge how much I owe to the very careful and original research provided by Professor Willis, in his "Architectural History of the Cathedral"; by Precentor Walcott, in his "Early Statutes" of Chichester; and Dean Stephen, in his "Diocesan History." The footnotes, which refer to the latter work, indicate the pages in the smaller edition. But the volume could never have been completed without the great help given to me on many occassions by Prebendary Bennett. His deep and intimate knowledge of the cathedral structure and its history was always at my disposal. It is to him, as well as to Dr. Codrington and Mr. Gordon P.G. Hills, I am still further indebted for much help in correcting the proofs and for many valuable suggestions. H.C.C. C O N T E N T S. CHAP. PAGE I. HISTORY OF THE CATHEDRAL............... 3 page 2 / 148 II. THE EXTERIOR.......................... 51 III. THE INTERIOR.......................... 81 IV. -

Devonshire Parish Registers. Marriages

942.35019 I Aalp I V.2 1379105 ! GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00726 5934 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/devonshireparish02phil General Editor ... ... T. M. Blagg, F.S.A. DEVONSHIRE PARISH REGISTERS n^arrlages. II. PHILLIMORE S PARISH REGISTERS SKRIES. VOL. CXXXV. (DEVON, VOL. 11.) Only one hundred and fifty copies printed. Devonshire Parish Registers. General Editor: THOS. M. BLAGG, F.S.A. v.^ VOL. II. Edited by A. TERRY SATTERFORD. Condon Issued to the Subscribers by Phillimore & Co., Ltd. 124, Chancery Lane. 1915- PREFACE. Six years have elapsed since tlie first volume of Devonshire Marriage Registers was issued and during those years the work- has been practically at a standstill, in strange contrast to the adjoining counties of Cornwall, Somerset, and Dorset, where the Marriage Registers of 133, 107 and 58 parishes respectively have now been printed. This lack of progress in Devon has been due partly to the death of Mr. W. P. W. Phillimore to whose inception the entire Series is due and who edited the first volume, but chiefly to the poor support forthcoming from Devon men, in comparison with that accorded to the Series in other counties by those interested in their Records. Thus the first volume for Devonshire was issued at a substantial loss. Now that the work has been resumed, it is hoped that the support received will be more proportionate to the size and importance of the county, and so will enable the Devonshire Marriage Registers to be printed on a uniform plan and with such regularity of output as will render them safe from further loss and readily accessible to the student and genealogical searcher. -

Durham Cathedral an Address

DURHAM CATHEDRAL AN ADDRESS DELIVERED SEPTEMBER 24, I879. BY W I L L I A M G R E E NWELL, M.A.. D.C.L.. F.R.S.. F.S.A. THIRD EDITION. WITH PLAN AND ILLUSTRATIONS. Durham : ANDREWS & CO.. 64. SADDLER STREET. 1889. D U R H A M : THOS. CALDCLEUGH, PRINTER. 70. SADDLER STREET. TO THE MEMORY OF William of Saint Carilef THIS ATTEMPT TO ILLUSTRATE THE NOBLE CHURCH WHICH HIS GENIUS AND PIETY HAVE BEQUEATHED TO US IS DEDICATED. 53494 PREFACE. THE following account of the Cathedral Church of Durham was addressed to the members of the Berwickshire Naturalists' Club and the Durham and Northumberland Archaeological and Architectural Society, at a joint meeting of the Societies, held in the Cathedral, on September 24, 1879. This will explain the form under which it appears, and, it is to be hoped, excuse the colloquial and somewhat desultory way in which the subject is treated. It was not the intention of the author of the address, when it was given, that it should appear in any other form than that of an abstract in the Transactions of the Societies to which it was delivered. Several of his friends, however, have thought that printed in externa it might be of service as a Guide Book to the Cathedral, and supply what has been too long wanting in illustration of the Church of Durham. To this wish he has assented, but with some reluctance, feeling how inadequate is such a treatment of a subject so important. Some additional matter has been supplied in the notes which will help to make it more useful than it was in its original form. -

Browns Strangers Handbook and Illustrated

l i u r C a th e d r a l W e st ro nt o lo n S a s b y , F , b g tto d tto r t Di , i , up igh tto f ro m No rt - W e st o lon Di , h , b g tto d tto o l on Di , i , b g tto E ast En d r t Di , , up igh tto d tto o lon Di , i , b g ’ tto f rom B s o s a la e o lo n Di , i h p P c , b g tto f 1 o m a la e r o n d s r t Di , P c G u , up igh tto d tto o lon Di , i , b tg" tto So t e w f r° cm the a e r ht Di , u h Vi L k , up ig tto d tto o lon Di , i ,”b g tto from H arn am o lo n Di , h , b g tto f ro m C ow an e o lon Di , L , b g tto S re from Clo s te rs r t Di , pi i , up igh tto f ro m th e R e r o lon Di , iv , b g tto d tto o lon Di , i b g ’ tto f ro m B s o s al a e o lon Di , i h p P c , b g tto W e s t o orw a o lon Di , D y , b g tto Stat e s i n W e s t ront r t Di , u F , up igh ’ tto B s o s a la e No rt o lo n Di , i h p P c , h , b g tto d tto So t o lon Di , i , u h , b g tto Clo s te r s Inte r or o lon Di , i , i , b g D tto C o r lo o n E a st r t i , h i ki g , up igh tto C o r and S r e e n loo n E ast o lo n Di , h i c ki g , b g tto C o r lo o n E a st r t Di , h i ki g , up igh tt o C o r loo n W e s t r t Di , h i ki g , up igh tto d tto o l on Di , i , b g tto C o r an d S r e e n loo n E a s t r t Di , h i c ki g , up igh tto d tto o lon Di , i , b g tto C o r a n d Na e lo o n W e s t o lo n Di , h i v ki g , b g tto a e E a st r t Di , N v , , up igh tto Na e lo o n E as t o lo n Di , v ki g , b g tto Na e loo n W e s t o lo n Di , v ki g , b g tto Re re d o s o lon Di , , b g tto d tto l t Di , i , up igh tt o ort and So t Tra nse ts o lo n Di , N h u h p , b g ’ i tto E a rl o f He rtf o rd s Mo n me nt r t D , u , up ig h tto ad C a e l o lo n Di , L y h p , b g tto Cha te r Ho s e Inte r or o lon Di , p u , i , b g ’ tto B s o H am lto n s o m o l o n Di , i h p i T b , b g ’ tto B s o Mo e rl s To m o l on Di , i h p b y b , b g S a l i s b u r P r t y , o u l t ry C r o s s , up igh tto H Stre e t ate So t o lon Di , igh G , u h , b g tto d tto Nort ri t Di , i , h , up gh ’ tt t nn t W t l n o S . -

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL the Enthronement of the Seventy

SALISBURY CATHEDRAL The Enthronement of the Seventy-Eighth Bishop of Salisbury The Right Reverend Nicholas Holtam Saturday 15 October 2011 at 12.00 noon Organ Music before the Service Prelude and Fugue in E minor bwv 548 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Sonata II in C minor Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) Choral II in B minor César Franck (1822–1890) Impromptu in G Walter Alcock (1861–1947) The Cathedral choirs are directed by David Halls. The Organist is Daniel Cook. The Choir of St Martin-in-the-Fields is directed by Andrew Earis. The anthem by James Whitbourn was commissioned for this service. The Bishop’s pectoral cross is a gift from the Chinese congregations at St Martin-in-the Fields. The jewelled and enamelled crozier was presented to the Cathedral by Canon Myers in 1909. The decorations are rich in symbolism. The main group represents Christ’s charge to St Peter. The Beast below the circular rim represents the powers of evil overcome by Our Lord’s atonement. The figures in the ivory boss below are the Blessed Virgin Mary and Child, St Aldhelm (with a harp), St Osmund (with a Sarum breviary) and Bishop Richard Poore (with a representation of the Cathedral). The bell ringers of St Martin-in-the-Fields have brought a portable tower to ring for their former Vicar. The image of the Hinton St Mary Mosaic is copyright © The Trustees of the British Museum. – 2 – Introductory Note Just on the outskirts of Salisbury is an ancient hamlet (now a flourishing and expanding suburb) called Bishopdown. -

Power Heraldry

Power Heraldry by Frank R. Power Comments and questions are welcome. [email protected] Heraldry is the study of coats of arms that are inherited symbols, or devices, called charges, displayed on a shield, or escutcheon, for the purpose of identifying individuals or families. It involves the art of devising, granting, and blazoning arms, tracing genealogies, and determining and ruling on questions of rank or protocol. Heraldry and genealogy have a long, collaborative relationship. Heraldry requires a knowledge of genealogy and heraldry has often been used as evidence to support genealogical conclusions. The basic role of both heraldry and genealogy is to identify and place individuals within the context of their families and if done well, within the wider historical context in which they lived. Heraldry can provide excellent clues and pointers to ancestry. The following tabulation of Power and related names, coats of arms, geographical locations, blazons (text descriptions), crests and mottoes, source references and notes along with the attached geographic distribution map are intended as a starting point for the use of heraldry in fleshing out our Power family history. For further information: Intro to Heraldry - A Primer for Genealogists: Heraldry, History & Inheritance By Kimberly Powell, About.com Guide http://genealogy.about.com/cs/heraldry/a/heraldry.htm RootsWeb's Guide to Tracing Family Trees Guide No. 19 Heraldry for Genealogists http://rwguide.rootsweb.ancestry.com/lesson19.htm Using Heraldry in Genealogical Research http://watsoncanet.webcon.net.au/blog/2010/10/20/using-heraldry-in-genealogical-research/ Articles from several sources which are directly or indirectly related to heraldry in Ireland. -

Poor-Poore Family

THE POOR-POORE FAMILY GATHERING J..T NEWBURYPORT, MASS., Sept. ll;th, 1881. NEW YORK: S. \V. GREE:O.'S SON, PRINTER., ELECTROTYPER .AND BINDER, 74 AND j6 BEEK~L-\X STREET. TI-IE PooR-PooRE FA1vIIL"'i.,. "' ,, G-ATl:·pn.rNG OJ.!' Tliii1 m:.,A.N:·J.'- ]fay. Lo11vin(; lhoir homf.ls 1 thoy llr<>Sscd tho Then followed 11.n int<'t'llliti&ion of 1m lwliol,l wit.h 11,1•rrni 0,l11111•ril l\1•.· H!'fli? n[,: con. in smrJI vos:•ols, l.'.nd ~otUml in tho frown hom· to IH1 m:ed a11 the pro~rnmnrn 1..:tatc>rl tlwir dtHeonclai:t:; n( l.,,] 1_1·. ,\ '.; ( llll [_: f:loaorni 'l'rlm1nlRl ltmmion oft,ha J?omo- iog foronts, whoro tboy foundod a. onmmon• for ''ront•wing olJ kin nc<p1rtintn.nce~ ,rnd 1wn.·1•e ol •.ho riv:•r ia i-1 ,,11,.• H·<·ln,1,.,,1 r .Poor .D',·.,mly fit An<.lov-or••-f.-iPooohoa by wo,,!th, orgll.nhe,1 on tho priuciplo3 of nn.tioo• ~ :Mn.i, .Hon .Porlc,y l'ooro und oti101•s. m11kiug tll➔ W 01rna." 'l'hn inBtrnction~ IIIOllll(•lin llprin,:, ,lild a,3 II ·:. :,,,:; i:•• -.1·,1:, a.I juetico by thn volulitary ooml1ination of l Tlie 1'001:1 cnmc ori~:irrnlly from \Vilt Lt this n';pud wcro follnw~,l to tho ldl1•r. nlong it i~ conAt,rntly lwin:t \ o: /1:'.,.:,l liy tho inhnhitnnts. i shire ]~tif.!hti,.1; Jolin Poor th\l nnc,>stor 'l'lio mr.mhora of tho falllily from Ohin othrr f.lll't>nm~, rivul<it~, ',r,,,.)·.", 1i1·ti1·" "l~rotn tho rook wlioro t of John M roor of thi~ city wi~s the 01u· fathors In os.ilo and Illinois shook hnn!ls with their kinl\• :incl trihnrnrici', 1111ti! wl11•a it l' · 1"11"i, llr8t Jnnd\:<.t; ~ firr,t, of the irnmo to come to Anwric11, in mt>n from l\1;~~l:lachu>iti.tll an1l N,,w tlw 1Hw:1n i:. -

Management Plan 2006

One NorthEast DURHAM CATHEDRAL AND CASTLE WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN November 2006 CHRIS BLANDFORD ASSOCIATES Environment Landscape Planning One NorthEast DURHAM CATHEDRAL AND CASTLE WORLD HERITAGE SITE MANAGEMENT PLAN Approved By: Dominic Watkins Signed: Position: Director Date: 9 November 2006 CHRIS BLANDFORD ASSOCIATES Environment Landscape Planning CONTENTS Foreword Acknowledgements Executive Summary 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 An Introduction to World Heritage 1.2 The Need for a WHS Management Plan 1.3 Status and Role of the Plan 1.4 Preparation of the Plan 1.5 Structure of the Plan 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE SITE 2.1 Location and Extent of the WHS 2.2 Proposed Boundary Changes to the Original Nomination 2.3 Historic Development of the World Heritage Site 2.4 Description of the WHS and its Environs 2.5 Intangible Values 2.6 Collections 2.7 Management and Ownership of the WHS 2.8 Planning and Policy Framework 2.9 Other Relevant Plans and Studies 3.0 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SITE 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Statement of Significance 3.3 Assessment of the Wider Value of the Site 4.0 MANAGEMENT ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Vision and Key Principles 4.3 Theme 1: Managing the World Heritage Site and its Setting 4.4 Theme 2: Conserving the Site and its Significances 4.5 Theme 3: Using the Site 4.6 Theme 4: Enhancing Understanding of the Site 4.7 Theme 5: Improving Access and Sustainable Transport 5.0 IMPLEMENTATION, MONITORING AND REVIEW 5.1 Implementing the Plan in Partnership 5.2 Action Plan 5.3 Monitoring and Review APPENDICES Appendix -

Pastoral Care According to the Bishops of England and Wales (C.1170 – 1228)

University of Cambridge Faculty of History PASTORAL CARE ACCORDING TO THE BISHOPS OF ENGLAND AND WALES (C.1170 – 1228) DAVID RUNCIMAN Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge Supervised by DR JULIE BARRAU Emmanuel College, Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2019 DECLARATION This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. ABSTRACT DAVID RUNCIMAN ‘Pastoral care according to the bishops of England and Wales (c.1170-1228)’ Church leaders have always been seen as shepherds, expected to feed their flock with teaching, to guide them to salvation, and to preserve them from threatening ‘wolves’. In the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, ideas about the specifics of these pastoral duties were developing rapidly, especially in the schools of Paris and at the papal curia. Scholarly assessments of the bishops of England and Wales in this period emphasise their political and administrative activities, but there is growing interest in their pastoral role. In this thesis, the texts produced by these bishops are examined. These texts, several of which had been neglected, form a corpus of evidence that has never before been assembled. Almost all of them had a pastoral application, and thus they reveal how bishops understood and exercised their pastoral duties. -

Sussex Archaeological Collections Relating to the History And

Gc M. 12 94^.2501 Su8c V.29 1295846 CWENEALOGY COLLECTiON \) ALLEN COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00724 4426 Sussex ^rci^aeologtcal gjoctetg^ SUSSEX arfl)afolo0iral ColUfttons, RELATING TO THE HISTORY AND ANTIQUITIES OF THE COUNTY. PUBLISHED BY Ciic Sussex ^rriiacologtcal Society. YOL. XXIX. SUSSEX: ALEX. RIYINaTON, HIGH STREET, LEWES. MDCCCLXXIX. CORRESPONDINa SOCIETIES, &c. The Society of Antiquaries of London. The Eoyal and Archaeological Association of Ireland. The British Archajological Association. The Camhrian ArchaBological Association, The Eoyal Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. La Societe des Antiquaires de Normandie. The Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society. The Essex Archaeological Society. The London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. The Somersetshire Archaeological Society. The Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshii-e. The United Architectural Societies of Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Noi'thampton, Bedfordshire, Worcestershire, and Leicestershire. The Kent Archaeological Society. The Surrey Areha;ological Society. The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. The Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Society. The State Paper Office. The College of Arms. — CONTENTS 1295846 PAGE Report .... vii Statement of Accounts . ix Lis t of Members xi Corresponding Societies ii Rules of Society xvii Erratum .... xix List of Illustrations 1. Bishops of Chichester, from Stigand to Sherborne. By Rev. MACKENZIE E. C. Walcott (continued from Vol. xxviii) 1 2. The Black Friars of Chichester. By Rev. C F. R. Palmer 39 3. The Lavingtons. By Rev. Thomas Debaey. 46 4. The Ancient British Coins of Sussex. By Ernest H. Willett, Esq. 72 5. The Hundred of Swanborough. By Joseph Cooper. 114 6. Ancient Cinder-heaps in East Sussex. By James RocK, Esq. 167 7.