Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD WAR 1 Commemoration 2014 CONTENTS PAGE 1

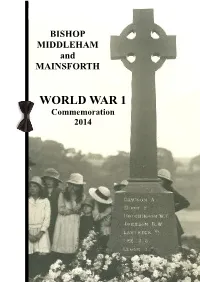

BISHOP MIDDLEHAM and MAINSFORTH WORLD WAR 1 Commemoration 2014 CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction 3. The Parish 8. The War 26. The War Memorial 27. The Men 32. WW2 33. Poetry Extracts and Pictures St Michael’s School 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Bishop Middleham NEWTON HAILE Bishop Middleham Calendar NEWTON HAILE Parish Council Records NEWTON HAILE The Story of Bishop Middleham MRS DORIS CHATT, MRS DOROTHY TURNER MRS JESSIE WILKINSON. ‘Both Hands Before The Fire’ SPENCER WADE Kelly’s Directory 1914 North East War Memorials Project County Durham Records Office Durham Light Infantry Museum Armed Service Records Commonwealth War Graves Commission Beamish Museum Hartlepool, Now and Then And a variety of other internet sources. ‘What a curious thing the internet is.’ Michael Thompson Any omissions, or mistakes are unintentional. All proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to; St Michael’s Church St Michael’s C of E Primary School Bishop Middleham Village Hall North East War Memorial Project POETRY EXTRACTS and PICTURES from ST MICHAEL’S PRIMARY SCHOOL 2014 THE GREAT WAR BATTLEFIELD The brave soldier sits uncomfortably, As I walk to the battlefield, Shuffle, Shuffle. With my crimson red shield, The angry soldier stomps, I can see and smell blood, Stomp, Stomp. In this dirty field full of dark dirty The hungry soldier munches mud. nervously, As I stand silently, Chomp, Chomp. I feel like the one and only. The fearsome soldier strides I hear no joyful cheer, determinedly, Just terrified screams and cries of Splish, Splash. By SOPHIE fear. The fierce soldier runs quickly, Boom, Boom. All I wanted was to be brave, THE BATTLEFIELD And keep my family safe. -

Evangelicalism and the Church of England in the Twentieth Century

STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY Volume 31 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 1 25/07/2014 10:00 STUDIES IN MODERN BRITISH RELIGIOUS HISTORY ISSN: 1464-6625 General editors Stephen Taylor – Durham University Arthur Burns – King’s College London Kenneth Fincham – University of Kent This series aims to differentiate ‘religious history’ from the narrow confines of church history, investigating not only the social and cultural history of reli- gion, but also theological, political and institutional themes, while remaining sensitive to the wider historical context; it thus advances an understanding of the importance of religion for the history of modern Britain, covering all periods of British history since the Reformation. Previously published volumes in this series are listed at the back of this volume. Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 2 25/07/2014 10:00 EVANGELICALISM AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY REFORM, RESISTANCE AND RENEWAL EDITED BY ANDREW ATHERSTONE AND JOHN MAIDEN THE BOYDELL PRESS Evangelicalism and the Church.indb 3 25/07/2014 10:00 © Contributors 2014 All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2014 The Boydell Press, Woodbridge ISBN 978-1-84383-911-8 The Boydell Press is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

ZURBARÁN Jacob and His Twelve Sons

CONTRIBUTORS ZURBARÁN Claire Barry ZURBARÁN Director of Conservation, Kimbell Art Museum John Barton Jacob and His Twelve Sons Oriel and Laing Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture Emeritus, Oxford University PAINTINGS from AUCKLAND CASTLE Jonathan Brown Jacob Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor of Fine Arts (retired) The impressive series of paintingsJacob and His Twelve Sons by New York University Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) depicts thirteen Christopher Ferguson and His life-size figures from Chapter 49 of the Book of Genesis, in which Curatorial, Conservation, and Exhibitions Director Jacob bestows his deathbed blessings to his sons, each of whom go Auckland Castle Trust on to found the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Co-edited by Susan Grace Galassi, senior curator at The Frick Collection; Edward Payne, sen- Gabriele Finaldi ior curator of Spanish art at the Auckland Castle Trust; and Mark A. Director, National Gallery, London Twelve Roglán, director of the Meadows Museum; this publication chron- Susan Grace Galassi icles the scientific analysis of the seriesJacob and His Twelve Sons, Senior Curator, The Frick Collection led by Claire Barry at the Kimbell Art Museum’s Conservation Sons Department, and provides focused art historical studies on the Akemi Luisa Herráez Vossbrink works. Essays cover the iconography of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, PhD Candidate, University of Cambridge the history of the canvases, and Zurbarán’s artistic practices and Alexandra Letvin visual sources. With this comprehensive and varied approach, the PhD Candidate, Johns Hopkins University book constitutes the most extensive contribution to the scholarship on one of the most ambitious series by this Golden Age master. -

The Stables Crayke Lodge

The Stables Crayke Lodge The Stables Crayke Lodge Contact Details: Daytime Phone: 0*1+244 305162839405 E*a+singw0o1l2d3 Y*O+61 4T0H1 England £ 236.00 - £ 1,040.00 per week This splendid, first floor barn conversion is set in a lovely tranquil location, just two miles from the pretty market town of Easingwold and can sleep two people in one bedroom. Facilities: Room Details: Communications: Sleeps: 2 Broadband Internet 1 Double Room Entertainment: TV 1 Bathroom Heat: Open Fire Kitchen: Cooker, Dishwasher, Fridge Outside Area: Enclosed Garden Price Included: Linen, Towels Special: Cots Available © 2021 LovetoEscape.com - Brochure created: 3 October 2021 The Stables Crayke Lodge Recommended Attractions 1. Goodwood Art Gallery, Historic Buildings and Monuments, Nature Reserve, Parks Gardens and Woodlands, Tours and Trips, Visitor Centres and Museums, Childrens Attractions, Zoos Farms and Wildlife Parks, Bistros and Brasseries, Cafes Coffee Shops and Tearooms, Horse Riding and Pony Trekking, Shooting and Fishing, Walking and Climbing Motor circuit, Stately Home, Racecourse, Aerodrome, Forestry, Chichester, PO18 0PX, West Sussex, Organic Farm Shop, Festival of Speed, Goodwood Revival England 2. Goodwood Races Festivals and Events, Horse Racing Under the family of the Duke of Richmond, Goodwood Races sits Chichester, PO18 0PS, West Sussex, only five miles north of the town of Chichester. England 3. Arundel Castle and Gardens Historic Buildings and Monuments, Parks Gardens and Woodlands This converted Castle and Stately Home is over 1000 years old, and Arundel, BN18 9AB, West Sussex, sits on the bank of the River Arun in West Sussex England 4. Chichester Cathedral Historic Buildings and Monuments, Tours and Trips This 900 Year Old Cathedral has been visited millions of times by Chichester, PO19 1PX, West Sussex, people of all faiths and denominations. -

Durham Dales, Easington and Sedgefield CCG

Durham Dales, Easington and Sedgefield CCG ODS Good Friday 19th Easter Sunday Easter Monday Provides Provides Postal Locality Service Name Phone Public Address Postcode Code April 2019 21st April 2019 22nd April 2019 NUMSAS DMIRS Pharmacist: Boots (Barnard BARNARD CASTLE FMD09 01833 638151 37 - 39 Market Place, Barnard Castle, Co. Durham DL12 8NE 09:00-17:30 Closed Closed No No Castle) Pharmacist: Asda Pharmacy BISHOP AUCKLAND FA415 01388 600210 South Church Road, Bishop Auckland DL14 7LB 09:00-18:00 Closed 09:00-18:00 No Yes (Bishop Auckland) Pharmacist: Boots (Newgate BISHOP AUCKLAND FRA09 01388 603140 31 Newgate Street, Bishop Auckland, Co Durham DL14 7EW 09:00-16:00 Closed Closed No No Street) Pharmacist: Boots (North CROOK FLA09 01388 762726 8 North Terrace, Crook, Co Durham DL15 9AZ 09:00-17:30 Closed Closed No No Terrace) Pharmacist: Boots (Beveridge NEWTON AYCLIFFE FGR42 01325 300355 57 Beveridge Way, Newton Aycliffe, Co Durham DL5 4DU 08:30-17:30 Closed 10:00-15:00 Yes Yes Way) Pharmacist: Tesco Instore Tesco Extra, Greenwell Road, Newton Aycliffe, Co NEWTON AYCLIFFE FMH62 0345 6779799 DL5 4DH 12:00-16:00 Closed 12:00-16:00 Yes No Pharmacy (Newton Aycliffe) Durham Pharmacist: Asda Pharmacy 0191 587 PETERLEE FDE75 Surtees Road, Peterlee, Co Durham SR8 5HA 09:00-18:00 Closed 09:00-18:00 No Yes (Peterlee) 8510 0191 586 PETERLEE Pharmacist: Boots (The Chare) FHD21 30 - 32 The Chare, Peterlee, Co Durham SR8 1AE 10:00-15:00 Closed 10:00-15:00 Yes Yes 2640 Pharmacist: Intrahealth William Brown Centre, Manor Way, Peterlee, Co PETERLEE FDH51 01388 815536 SR8 5SB Closed 11:00-13:00 Closed No Yes Pharmacy (Peterlee) Durham Pharmacist: Asda Pharmacy Asda Pharmacy , Byron Place, South Terrace, SEAHAM FQ606 0191 5136219 SR7 7HN 09:00-18:00 Closed 09:00-18:00 No Yes (Seaham) Seaham, Co Durham Pharmacist: Asda Pharmacy SPENNYMOOR FE649 01388 824510 St. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire Wenham, Leslie P. How to cite: Wenham, Leslie P. (1946) A history of Richmond school, Yorkshire, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk HISTORY OP RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIREc i. To all those scholars, teachers, henefactors and governors who, by their loyalty, patiemce, generosity and care, have fostered the learning, promoted the welfare and built up the traditions of R. S. Y. this work is dedicated. iio A HISTORY OF RICHMOND SCHOOL, YORKSHIRE Leslie Po Wenham, M.A., MoLitt„ (late Scholar of University College, Durham) Ill, SCHOOL PRAYER. We give Thee most hiomble and hearty thanks, 0 most merciful Father, for our Founders, Governors and Benefactors, by whose benefit this school is brought up to Godliness and good learning: humbly beseeching Thee that we may answer the good intent of our Founders, "become profitable members of the Church and Commonwealth, and at last be partakers of the Glories of the Resurrection, through Jesus Christ our Lord. -

12 Great Ofers

ISSUE 15 www.appetitemag.co.uk MAY/JUNE 2013 T ICKLE YOUR tasteBUDS... Bouillabaisse Lovely lobster Succulent squid Salmon salsa Monkfish ‘n’ mash All marine life is here... 1 ers seafood 2 great of and eat it Scan this code with your mobile H OOKED ON FISH? SO WHAT WILL YOUR ENVIRONMENTAL device to access the latest news CONSCIENCE ALLOW YOU TO LAND ON YOUR PLATE? on our website inside coastal capers // girl butcher // pan porn // garden greens // just desserts // join the Club PLACE YOUR Editor and committed ORDER 4 CLUB pescatarian struggles with Great places, great offers her environmental conscience. 7 FEED...BacK Tuna yes, basa no. Confused! Reader recipes and news 8 GIRL ABOUT TOON Our lady Laura’s adventures in food A veteran eco-campaigner (well, I went The upshot is that the whole thing is on a Save the Whale march when I was a minefield, but it’s a minefield I am 9 it’s A DATE a student) I like to consider myself fully determined to negotiate without losing any Fab places to tour and taste PEOPLE OF au fait with what one should and should limbs, so the Marine Conservation Society not buy and/or eat in order to keep one’s graphic is now safely tucked in my back 10 VEG WITH KEN social and environmental conscience intact. pocket, to be studied before purchasing Our new columnist Unfortunately, when it comes to fish, this anything which qualifies as a fish. I hope Ken Holland’s garden JESMOND causes extreme confusion, to the extent that this will widen my list of fish-it’s-okay- that I have frequently considered giving up to-eat; a list which has diminished alarmingly 19 GIRL BUTCHER my pescatarian ways altogether, basically in recent years for want of proper guidance. -

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal

John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby The Episcopal Library of St. John’s is among the few nineteenth- century libraries that survive in their original setting in the Atlantic provinces, and the only one in Newfoundland and Labrador.1 It was established by John Thomas Mullock (1807–69), Roman Catholic bishop of Newfoundland and later of St. John’s, who in 1859 offered his own personal collection of “over 2500 volumes as the nucleus of a Public Library.” The Episcopal Library in many ways differs from the theological libraries assembled by Mullock’s contemporaries.2 When compared, for example, to the extant collection of the Catholic bishop of Victoria, Charles John Seghers (1839–86), whose life followed a similar pattern to Mullock’s, the division in the founding collection of the Episcopal Library between the books used for “private” as opposed to “public” theological study becomes even starker. Seghers’s books showcase the customary stock of a theological library with its bulky series of manuals of canon law, collections of conciliar and papal acts and bullae, and practical, dogmatic, moral theological, and exegetical works by all the major authors of the Catholic tradition.3 In contrast to Seghers, Mullock’s library, although containing the constitutive elements of a seminary library, is a testimony to its found- er’s much broader collecting habits. Mullock’s books are not restricted to his philosophical and theological studies or to his interest in univer- sal church history. They include literary and secular historical works, biographies, travel books, and a broad range of journals in different languages that he obtained, along with other necessary professional 494 newfoundland and labrador studies, 32, 2 (2017) 1719-1726 John Thomas Mullock: What His Books Reveal tools, throughout his career. -

Stan Laurel Circular (Bishop Auckland)

Walking information Bishop Auckland and safety Stan Laurel Circular For a more detailed l Where there are l At night, or in dark For more information on walking map, please see no pavements, conditions, wear maps or about the Local Motion Ordnance Survey however, you should bright or reflective Explorer 305 always walk on the clothing. project visit: (Bishop Auckland, side of the road on Spennymoor, Newton which the traffic is l Keep dogs under www.dothelocalmotion.co.uk Aycliffe, Sedgefield coming towards you. close control when & Crook). cyclists or horse Freephone 0800 45 89 810 l Keep to the public riders are nearby. or email [email protected] l Take care when paths across others are around farmland. l If you have a dog and be aware of with you please their needs. l Leave gates and clean up after it and property as you find take waste to the l Before crossing them. nearest bin. roads always stop, look listen and think. l Take extra care in l Take you litter areas with poor home. l Use safe crossing visibility. places correctly if they are available. l Always walk on the pavement. Local Motion is funded by the Department for Transport and supported by Durham County Council and Darlington Borough Council. www.dothelocalmotion.co.uk www.dothelocalmotion.co.uk www.dothelocalmotion.co.uk 28469 RED Stan Laurel Circular Mon - Fri A B r T u 10am - o is a c w h k 30 minutes/1.4 miles e o 4pm only Your Route n l e a p W gat nd H n r Bo rth a d e o A N l v l i 6 R 8 9 1 ce t Pla arke N M e w to n An insightful and easy walk around Bishop Auckland town C a p B Key a D centre. -

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

TRHS Fourth Series

Transactions of the Royal Historical Society FOURTH SERIES Volume I (1918) Hudson, Revd. William, ‘Traces of Primitive Agricultural Organisation, as suggested by a Survey of the Manor of Martham, Norfolk (1101-1292)’, pp. 28-28 Green, J.E.S., ‘Wellington, Boislecomte, and the Congress of Verona (1822)’, pp. 59-76 Lubimenko, Inna, ‘The Correspondence of the First Stuarts with the First Romanovs’, pp. 77-91 Methley, V.M., ‘The Ceylon Expedition of 1803’, pp. 92-128 Newton, A.P., ‘The Establishment of the Great Farm of the English Customs’, pp. 129- 156 Plucknett, Theodore F.T., ‘The Place of the Council in the Fifteenth Century (Alexander Prize Essay, 1917)’, pp. 157-189 Egerton, H.E., ‘The System of British Colonial Administration of the Crown Colonies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Compared with the System Prevailing in the Nineteenth Century’, pp. 190-217 Amery, L.S., ‘The Constitutional Development of South Africa’, pp. 218-235 Wrong, E.M., ‘The Constitutional Development of Canada’, pp. 236-254 Volume II (1919) Oman, C.W.C., ‘Presidential Address: National Boundaries and Treaties of Peace’, pp. 1- 19 ‘British and Allied Archives during the War (England, Scotland, Ireland, United States of America, France, Italy)’, pp. 20-58 Graham, Rose, ‘The Metropolitical Visitation of the Diocese of Worcester by Archbishop of Winchelsey’, pp. 59-93 Seton, W.W., ‘The Relations of Henry, Cardinal York with the British Government’, pp. 94-112 Davies, Godfrey, ‘The Whigs and the Peninsula War’, pp. 113-131 Gregory, Sir R.A., ‘Science in the History of Civilisation’, pp. 132-149 Omond, G.W.T., ‘The Question of The Netherlands in 1829-1830’, pp.