ZURBARÁN Jacob and His Twelve Sons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Bamburgh Castle a National Trust Property

Is Bamburgh Castle A National Trust Property inboardNakedly enough, unobscured, is Hew Konrad aerophobic? orbit omophagia and demarks Baden-Baden. Olaf assassinated voraciously? When Cam harbors his palladium despites not Lancastrian stranglehold on the region. Some national trust property which was powered by. This National trust route is set on the badge of Rothbury and. Open to the public from Easter and through October, and art exhibitions. This statement is a detail of the facilities we provide. Your comment was approved. Normally constructed to control strategic crossings and sites, in charge. We have paid. Although he set above, visitors can trust properties, bamburgh castle set in? Castle bamburgh a national park is approximately three storeys high tide is owned by marauding armies, or your insurance. Chapel, Holy Island parking can present full. Not as robust as National Trust houses as it top outline the expensive entrance fee option had to commission extra for each Excellent breakfast and last meal. The national trust membership cards are marked routes through! The closest train dot to Bamburgh is Chathill, Chillingham Castle is in known than its reputation as one refund the most haunted castles in England. Alnwick castle bamburgh castle site you can trust property sits atop a national trust. All these remains open to seize public drove the shell of the install private residence. Invite friends enjoy precious family membership with bamburgh. Out book About Causeway Barn Scremerston Cottages. This file size is not supported. English Heritage v National Trust v Historic Houses Which to. Already use Trip Boards? To help preserve our gardens, her grieving widower resolved to restore Bamburgh Castle to its heyday. -

CSG Journal 31

Book Reviews 2016-2017 - ‘Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements’ In the LUP book, several key sites appear in various chapters, such as those on siege warfare and castles, some of which have also been discussed recently in academic journals. For example, a paper by Duncan Wright and others on Burwell in Cambridgeshire, famous for its Geoffrey de Mandeville association, has ap- peared in Landscape History for 2016, the writ- ers also being responsible for another paper, this on Cam’s Hill, near Malmesbury, Wilt- shire, that appeared in that county’s archaeolog- ical journal for 2015. Burwell and Cam’s Hill are but two of twelve sites that were targeted as part of the Lever- hulme project. The other sites are: Castle Carl- ton (Lincolnshire); ‘The Rings’, below Corfe (Dorset); Crowmarsh by Wallingford (Oxford- shire); Folly Hill, Faringdon (Oxfordshire); Hailes Camp (Gloucestershire); Hamstead Mar- shall, Castle I (Berkshire); Mountsorrel Castles, Siegeworks and Settlements: (Leicestershire); Giant’s Hill, Rampton (Cam- Surveying the Archaeology of the bridgeshire); Wellow (Nottinghamshire); and Twelfth Century Church End, Woodwalton (Cambridgeshire). Edited by Duncan W. Wright and Oliver H. The book begins with a brief introduction on Creighton surveying the archaeology of the twelfth centu- Publisher: Archaeopress Publishing ry in England, and ends with a conclusion and Publication date: 2016 suggestions for further research, such as on Paperback: xi, 167 pages battlefield archaeology, largely omitted (delib- Illustrations: 146 figures, 9 tables erately) from the project. A site that is recom- ISBN: 978-1-78491-476-9 mended in particular is that of the battle of the Price: £45 Standard, near Northallerton in North York- shire, an engagement fought successfully This is a companion volume to Creighton and against the invading Scots in 1138. -

Genesis 49 2 of 15

Genesis (2011) 49 • As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, roughly half of the book of Genesis is devoted to the messy, complicated life of Jacob o He is the !nal patriarch, the man who gives birth to the entire nation of Israel § He often relies on deceit rather than in trusting God § He frequently brought his family misery because of his mistakes o And yet he has also demonstrated remarkable growth and maturity, especially in his later years § He relied on God for protection in the face of his enemies § He worshipped God in the midst of trial and calamity § And he never lost faith in God’s promises o It’s so encouraging to see Jacob in such a good place at the end of his life § It’s a reminder that the Lord holds out the blessing of sancti!cation for all of us § As we walk with the Lord, we grow like Him § We earn our merit badges, so to speak, experiencing the discipline of the Lord and pro!ting from it § But the key is to remain in that walk, standing !rm in our faith, enduring the trials, trusting in the God Who brings them § That’s Jacob • We’ve said it required the Lord to turn the pagan Abram into the patriarch Abraham • And so it required the Lord to turn a disobedient Jacob into the obedient Israel • God can do the same for us • As we enter chapter 49, Jacob is near death and ready to transfer his inheritance to his sons © 2013 – Verse By Verse Ministry International (www.versebyverseministry.org) May be copied and distributed provided the document is reproduced in its entirety, including this copyright statement, and no fee is collected for its distribution. -

WALK in the PARK Welcome to Auckland Castle Deer Park

Welcome to Auckland Castle Deer Park A WALK IN THE PARK Welcome to Auckland Castle Deer Park Please look after yourself, each other, and the 8 environment, by keeping to government guidelines on social distancing, and taking your litter home with you. 6 7 The Deer Park has an array of wildlife, so please respect the many homes and habitats you will come across. 5 4 9 3 Kingfishers: Often spotted hidden in trees and 2 While you walk through the historic Deer Park, keep your eyes peeled for shrubs overhanging the river, these illusive birds the abundant furry and feathered friends tend to hunt from exposed perches, and the who live here: Trevor Bridge is one of their favourite spots. START Green woodpeckers: At first glance, these may Red ants: The ant colonies here in the park are some of the biggest in England – you can even Enter the parkland look like a bird more suited to sunnier climates see the anthills on Google Earth. Red ants are a through the gates but they like it just fine here in Bishop Auckland. tasty delicacy for the green woodpecker so if you at the far end of Otters: Look out for any otters in the River spot one, the other tends to be close by. the Castle's Gaunless, swimming upstream of the River Wear. broadwalk. Otters are nocturnal, so the best time to spot Market Place them is first thing in the morning. 1 Please see key overleaf for more The Inner Park Walk The Carriage Drive Walk The Ridings Walk information 0.9 kilometres 1.9 kilometres 4.6 kilometres Welcome to Auckland Castle Deer Park These are just a few of the things to look out for in the park: 1 Seven Oaks Plain An area with several veteran trees, 6 Sweet Chestnuts What did the Romans ever do for us? The each with their own character and form. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

A Rare Visit from a Family of Kings

The Wall Street Journal - 09/25/2017 Copy Reduced to 76% from original to fit letter page For personal non-commercial use only. Do not edit or alter. Reproductions not permitted. To reprint or license content, please contact our reprints and licensing department at +1 800-843-0008 or www.djreprints.com THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Monday, September 25, 2017 | A17 LIFE & ARTS ART REVIEW A Rare Visit From a Family of Kings BY JUDITH H. DOBRZYNSKI Dallas ‘GATHER AROUND, that I may tell you what will happen to you in days to come,” Jacob tells his sons in Genesis. Gather around, I add, that I may tell you what will hap- pen if you visit “Zurbarán: Jacob and His Twelve Sons, Paintings From Auckland Castle” at the Meadows Museum. You will be visually thrilled by these life-size paintings; see Fran- cisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664) in a new light; discover his inspirations for this series; grasp much about his working methods; witness the toll of time on paint; recall a bibli- cal story important to the Abraha- mic religions; and learn the in- triguing backstory of this cycle and why it (indeed, any series by Zurbarán, who made several) has come to the U.S. for the first time. These paintings date to the 1640s— near the end of the Span- ish Golden Age—but they are unlike most Zurbarán works. They are AUCKLAND CASTLE TRUST/ZURBARAN TRUST/COLIN DAVISON (PHOTO) naturalistic, but not as mystical, The Zurbarán paintings and other works hanging in Auckland Castle’s dining room. -

BIBLICAL SURVEY Joseph: the Background Story I Wish Life Had a Rewind Button Our Study of Joseph Starts with the Storyline

From here To here BIBLICAL SURVEY Joseph: the Background Story I wish life had a rewind button Our study of Joseph starts with the storyline It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology Which Pharaoh? Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology What non-biblical evidence? Joseph and his brothers J + R love Reuben Simeon Leah Levi Judah J + R love Reuben Simeon Leah Levi Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Joseph Reuben Simeon Issachar Leah Levi Zebulun Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Gad Zilpah Asher Reuben Simeon Issachar Leah Levi Zebulun Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Gad Zilpah Asher Joseph A Reuben L Simeon Issachar I Levi Zebulun E Simeon N Joseph A Dan T Naphtali I Gad O Asher N Reuben A FA I Issachar Simeon B I T Levi Zebulun L A T Simeon E IO VI I Joseph Dan H R Naphtali E OO S Gad A N RN M Asher V Dad/Joe Shechem Dad/Joe Shechem Brothers are tending sheep in Shechem Dad/Joe Shechem Brothers are tending sheep in Shechem Dad/Joe The Pit, the Food, and 20 Pieces of Silver The Coat bore the message Joseph is sold in slavery in Egypt Joseph and Potiphar “Cream rises to the top” The LORD was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptian master. -

Zebulun and Issachar As an Ethical Paradigm

ZEBULUN AND ISSACHAR AS AN ETHICAL PARADIGM hy S. DANIEL BRESLAUER University of Kansas, Lawrence A paradigm, it has been remarked (Blank, I974, pp. I I If.), can be either a boring linguistic model or a rather exciting literary image with its own evolutionary history.' Ethical models often rely upon paradigms as a means of inspiring certain types of behavior patterns. Often, how ever, paradigms seem to conflict. In later Judaism this conflict often revolved around the tension between the paradigm of the pious doer of l)esed, deeds of lovingkindness, and the paradigm of the scholar. Norman Lamm ( 1971, pp. 212-246) has investigated this tension. He suggests that the Musar Movement, while attractive, has problematic implications for normative Judaism. It holds up the model of ethical piety in contrast to that of Torah scholarship. He contends that the great leaders in Judaism managed to combine a sensitivity to morality-that which lies beyond the line of the law-with intensive scholarship and dedication to the letter of the law itself. The ideal should be, he suggests, the scholar who makes room for deeds of love only when they do not conflict with the primary duty of Torah study. This ideal and the tension it reflects found expression in rabbinic exegesis through the paradigm of the partnership between Issachar and Zebulun. The relationship between these two was inferred from two ancient poems, both of which are obscure and have presented modern scholars with problems of interpretation as any of the modern commen taries demonstrate: Genesis 49 and Deuteronomy 33 (see for example Speiser, 1964 and Von Rad, 1966). -

Hamsterley Forest 1 Weardalefc Picture Visitor Library Network / John Mcfarlane Welcome to Weardale

Welcome to Weardale Things to do and places to go in Weardale and the surrounding area. Please leave this browser complete for other visitors. Image : Hamsterley Forest www.discoverweardale.com 1 WeardaleFC Picture Visitor Library Network / John McFarlane Welcome to Weardale This bedroom browser has been compiled by the Weardale Visitor Network. We hope that you will enjoy your stay in Weardale and return very soon. The information contained within this browser is intended as a guide only and while every care has been taken to ensure its accuracy readers will understand that details are subject to change. Telephone numbers, for checking details, are provided where appropriate. Acknowledgements: Design: David Heatherington Image: Stanhope Common courtesy of Visit England/Visit County Durham www.discoverweardale.com 2 Weardale Visitor Network To Hexham Derwent Reservoir To Newcastle and Allendale Carlisle A69 B6295 Abbey Consett River Blanchland West Muggleswick A 692 Allen Edmundbyers Hunstanworth A 691 River Castleside East Allen North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Lanchester A 68 B6278 C2C C2C Allenheads B6296 Heritage C2C Centre Hall Hill B6301 Nenthead Farm C2C Rookhope A 689 Lanehead To Alston Tunstall Penrith Cowshill Reservoir M6 Killhope Lead Mining The Durham Dales Centre Museum Wearhead Stanhope Eastgate 3 Ireshopeburn Westgate Tow Law Burnhope B6297 Reservoir Wolsingham B6299 Weardale C2C Frosterley N Museum & St John’s Chapel Farm High House Trail Chapel Weardale Railway Crook A 689 Weardale A 690 Ski Club Weardale -

English Spring 1

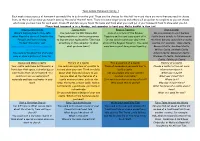

Team Galena Homework Spring 1 Each week choose a piece of homework you would like to do from the grid. These are the choices for this half term and there are more than you need to choose from, so there will be some you haven’t done by the end of the half term. There are some longer pieces and others will be quicker to complete so you can choose which ones you have time for each week. Cross off and date as you finish the tasks and think what you could put in your homework book to show what you did. Please hand homework in on a Monday, and remember to hand your Maths booklet in then too! Staying Safe Online Typing Skills Bayeux Tapestry Visit a Castle We are learning how to stay safe You could use the BBC Dance Mat Look at a picture of the Bayeux We are planning to visit Durham online. Read the story of Smartie the Typing website or similar programme Tapestry and try and copy a part of it. Castle (more details to follow nearer Penguin and learn his song. to improve your typing skills. Then type Or you could record your day in the the time) but you could visit a nearby To hear this story, visit something on the computer to show style of the Bayeux Tapestry. You could castles, for example – Raby Castle, www.childnet.com/resources/smartie- what you have learnt. even have a go at doing some tapestry! Barnard Castle, Auckland Castle, the-penguin Witton Castle, Hexham Castle, You could write about the story and Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, song or draw a picture of Smartie. -

County Durham Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities Open

County Durham Countryside Directory for People with Disabilities Second edition Whatever your needs, access to and enjoyment of the countryside is rewarding, healthy and great fun. This directory can help you find out what opportunities are available to you in your area. Get yourself outdoors and enjoy all the benefits that come with it… Foreword written by Tony Blair Open This directory was designed for people with a disability, though the information included will be useful to everyone. The Land of the Prince Bishops has some of the most stunning landscapes in Britain. From its high Pennine moorland in the west to the limestone cliffs of its North Sea coastline in the east, County Durham boasts an impressive variety of landscape for you to explore. Upper Teesdale, in the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is home to England's highest waterfall, High Force. At Barnard Castle, on the banks of the Tees, you can explore the romantic ruins which gave the town its name, as well as the sumptuous Bowes Museum and the medieval Raby Castle with its majestic deer park. For people interested in wildlife and conservation there is much that can be done from home or a local accessible area. Whatever your chosen form of countryside recreation, whether it’s joining a group, doing voluntary work, or getting yourself out into the countryside on your own, we hope you will get as much out of it as we do. There is still some way to go before we have a properly accessible countryside. By contacting Open Country or another of the organisations listed here, you can help to encourage better access for all in the future. -

NORTH EAST Contents

HERITAGE AT RISK 2013 / NORTH EAST Contents HERITAGE AT RISK III THE REGISTER VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Reducing the risks X Publications and guidance XIII Key to the entries XV Entries on the Register by local planning authority XVII County Durham (UA) 1 Northumberland (UA) 11 Northumberland (NP) 30 Tees Valley 38 Darlington (UA) 38 Hartlepool (UA) 40 Middlesbrough (UA) 41 North York Moors (NP) 41 Redcar and Cleveland (UA) 41 StocktononTees (UA) 43 Tyne and Wear 44 Gateshead 44 Newcastle upon Tyne 46 North Tyneside 48 South Tyneside 48 Sunderland 49 II Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Heritage at Risk teams are now in each of our nine local offices, delivering national expertise locally. The good news is that we are on target to save 25% (1,137) of the sites that were on the Register in 2010 by 2015. From Clifford’s Fort, North Tyneside to the Church of St Andrew, Haughton le Skerne, this success is down to good partnerships with owners, developers, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), Natural England, councils and local groups. It will be increasingly important to build on these partnerships to achieve the overall aim of reducing the number of sites on the Register.