Zebulun and Issachar As an Ethical Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ZURBARÁN Jacob and His Twelve Sons

CONTRIBUTORS ZURBARÁN Claire Barry ZURBARÁN Director of Conservation, Kimbell Art Museum John Barton Jacob and His Twelve Sons Oriel and Laing Professor of the Interpretation of Holy Scripture Emeritus, Oxford University PAINTINGS from AUCKLAND CASTLE Jonathan Brown Jacob Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor of Fine Arts (retired) The impressive series of paintingsJacob and His Twelve Sons by New York University Spanish master Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664) depicts thirteen Christopher Ferguson and His life-size figures from Chapter 49 of the Book of Genesis, in which Curatorial, Conservation, and Exhibitions Director Jacob bestows his deathbed blessings to his sons, each of whom go Auckland Castle Trust on to found the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Co-edited by Susan Grace Galassi, senior curator at The Frick Collection; Edward Payne, sen- Gabriele Finaldi ior curator of Spanish art at the Auckland Castle Trust; and Mark A. Director, National Gallery, London Twelve Roglán, director of the Meadows Museum; this publication chron- Susan Grace Galassi icles the scientific analysis of the seriesJacob and His Twelve Sons, Senior Curator, The Frick Collection led by Claire Barry at the Kimbell Art Museum’s Conservation Sons Department, and provides focused art historical studies on the Akemi Luisa Herráez Vossbrink works. Essays cover the iconography of the Twelve Tribes of Israel, PhD Candidate, University of Cambridge the history of the canvases, and Zurbarán’s artistic practices and Alexandra Letvin visual sources. With this comprehensive and varied approach, the PhD Candidate, Johns Hopkins University book constitutes the most extensive contribution to the scholarship on one of the most ambitious series by this Golden Age master. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

Genesis 49 2 of 15

Genesis (2011) 49 • As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, roughly half of the book of Genesis is devoted to the messy, complicated life of Jacob o He is the !nal patriarch, the man who gives birth to the entire nation of Israel § He often relies on deceit rather than in trusting God § He frequently brought his family misery because of his mistakes o And yet he has also demonstrated remarkable growth and maturity, especially in his later years § He relied on God for protection in the face of his enemies § He worshipped God in the midst of trial and calamity § And he never lost faith in God’s promises o It’s so encouraging to see Jacob in such a good place at the end of his life § It’s a reminder that the Lord holds out the blessing of sancti!cation for all of us § As we walk with the Lord, we grow like Him § We earn our merit badges, so to speak, experiencing the discipline of the Lord and pro!ting from it § But the key is to remain in that walk, standing !rm in our faith, enduring the trials, trusting in the God Who brings them § That’s Jacob • We’ve said it required the Lord to turn the pagan Abram into the patriarch Abraham • And so it required the Lord to turn a disobedient Jacob into the obedient Israel • God can do the same for us • As we enter chapter 49, Jacob is near death and ready to transfer his inheritance to his sons © 2013 – Verse By Verse Ministry International (www.versebyverseministry.org) May be copied and distributed provided the document is reproduced in its entirety, including this copyright statement, and no fee is collected for its distribution. -

Stories of the Prophets

Stories of the Prophets Written by Al-Imam ibn Kathir Translated by Muhammad Mustapha Geme’ah, Al-Azhar Stories of the Prophets Al-Imam ibn Kathir Contents 1. Prophet Adam 2. Prophet Idris (Enoch) 3. Prophet Nuh (Noah) 4. Prophet Hud 5. Prophet Salih 6. Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 7. Prophet Isma'il (Ishmael) 8. Prophet Ishaq (Isaac) 9. Prophet Yaqub (Jacob) 10. Prophet Lot (Lot) 11. Prophet Shuaib 12. Prophet Yusuf (Joseph) 13. Prophet Ayoub (Job) 14 . Prophet Dhul-Kifl 15. Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 16. Prophet Musa (Moses) & Harun (Aaron) 17. Prophet Hizqeel (Ezekiel) 18. Prophet Elyas (Elisha) 19. Prophet Shammil (Samuel) 20. Prophet Dawud (David) 21. Prophet Sulaiman (Soloman) 22. Prophet Shia (Isaiah) 23. Prophet Aramaya (Jeremiah) 24. Prophet Daniel 25. Prophet Uzair (Ezra) 26. Prophet Zakariyah (Zechariah) 27. Prophet Yahya (John) 28. Prophet Isa (Jesus) 29. Prophet Muhammad Prophet Adam Informing the Angels About Adam Allah the Almighty revealed: "Remember when your Lord said to the angels: 'Verily, I am going to place mankind generations after generations on earth.' They said: 'Will You place therein those who will make mischief therein and shed blood, while we glorify You with praises and thanks (exalted be You above all that they associate with You as partners) and sanctify You.' Allah said: 'I know that which you do not know.' Allah taught Adam all the names of everything, then He showed them to the angels and said: "Tell Me the names of these if you are truthful." They (angels) said: "Glory be to You, we have no knowledge except what You have taught us. -

BIBLICAL SURVEY Joseph: the Background Story I Wish Life Had a Rewind Button Our Study of Joseph Starts with the Storyline

From here To here BIBLICAL SURVEY Joseph: the Background Story I wish life had a rewind button Our study of Joseph starts with the storyline It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis It is the longest narrative in Genesis Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology Which Pharaoh? Beyond the Joseph storyline are important questions of history and archaeology What non-biblical evidence? Joseph and his brothers J + R love Reuben Simeon Leah Levi Judah J + R love Reuben Simeon Leah Levi Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Joseph Reuben Simeon Issachar Leah Levi Zebulun Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Gad Zilpah Asher Reuben Simeon Issachar Leah Levi Zebulun Judah Bilhah Dan J + R Naphtali love Gad Zilpah Asher Joseph A Reuben L Simeon Issachar I Levi Zebulun E Simeon N Joseph A Dan T Naphtali I Gad O Asher N Reuben A FA I Issachar Simeon B I T Levi Zebulun L A T Simeon E IO VI I Joseph Dan H R Naphtali E OO S Gad A N RN M Asher V Dad/Joe Shechem Dad/Joe Shechem Brothers are tending sheep in Shechem Dad/Joe Shechem Brothers are tending sheep in Shechem Dad/Joe The Pit, the Food, and 20 Pieces of Silver The Coat bore the message Joseph is sold in slavery in Egypt Joseph and Potiphar “Cream rises to the top” The LORD was with Joseph, and he became a successful man, and he was in the house of his Egyptian master. -

Rachel and Leah

1 Rachel and Leah Like brother stories, a sister story is a narrative paradigm that construes the family primarily upon its horizontal axis. In a sister story, identity is determined and the narrative is defined by the sibling bond, as opposed to the more hierarchical parent-child relationship. As I note in my introduction, brother stories dominate the Bible. By the time we meet sisters Rachel and Leah in Genesis 29, Cain has killed Abel, Isaac has usurped Ishmael, and Jacob has deceived Esau. At the conclusion of Rachel and Leah’s sister story, brothers return to the spotlight as Joseph and his brothers become the focus of the narrative. The Bible’s prevailing trope of fraternal rivalry is essentially about patrilineal descent in which paired brothers fight for their father’s and for God’s blessing. Pairing the brothers helps focus the rivalry and makes clear who is the elder and who is the younger and who, therefore, should have the legitimate claim to their father’s property.1 There can be only one winner, one blessed heir in the patrilineal narratives. Naturally, a good story defies cultural expectations, and younger brothers, more often than not, claim their father’s and God’s blessings. Examining this motif in separate works, both Frederick E. Greenspahn and Jon D. Levenson observe how the status of the Bible’s younger sons reflects Israel’s status, and how their stories reflect Israel’s national story.2 Like Israel, younger sons have no inherent right to the status they acquire in the course of their narratives.3 And like Israel, younger sons must experience exile and humiliation to acquire their blessings.4 Isaac faces his father’s knife. -

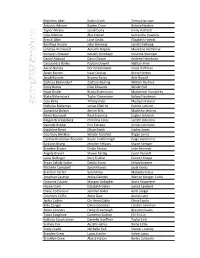

Spring 2017 Dean's List

Matthew Abel Katlin Crock Tressa Harrison Zebulun Adreon Baylee Crow Bobbie Haskins Taylor Ahrens Jacob Curry Emily Hatfield Cole Alleman Alec Dalton Samantha Hawkins Brandi Allen Lane Dedic Elizabeth Heerdt Boniface Anozie John Denning Jarrett Hellweg Lyndsay Arrowood Autumn Depew Madeline Helminiak Kamaryn Atwater Ketzalli Dondiego Johanna Hennigar Daniel Atwood Gavin Dostal Andrew Henriksen Cassaundra Bailey Payton Dowell Nathan Hine Aaron Barnes Dori Dreckmeier Trace Hoffman Adam Barnes Isaac Dunlap Avery Horton Jacob Barnett Brenna Eaves Arin Howell Zachary Beelendorf Zachary Ebeling William Hudnut Emily Bemis Elise Edwards Nicole Hull Hope Binder Brady Eisenmann Mackenzie Humphrey Blake Birkenstock Taylor Eisenmann Kelsey Hyndman Cole Birky Tiffany Elder Madisyn Ireland Nicholas Blakeman James Ellefritz Patrick Jackson Samantha Bolton Aminn Ellis Matthew Jenkins Remy Bousquet Raul Espinoza Eugina Johnson Megan Brackelsberg Christina Estes Jarrett Johnston Danielle Bredar Erin Estrada Kristin Johnston Madeline Brent Ethan Faeth Harley Jones Courtney Brinkley Schylar Fairchild Regan Jones Cynthia Brinkman-Roysdon Kaylin Featheringill Paige Kammerer Kaitlynn Broeg Jennifer Fellows Shane Kemper Braeden Brown Drake Fenton Jade Kennedy Angela Bryant Shawn Ferdig Jason Kensett Laine Bullinger Kory Fischer Connor Knepp Bryan Callaly-Sutter Debby Foust Kelsey Kramer Michelle Campbell Sarah Francis Jayla Kreiss Brandon Carter Sarah Frey Makaela Kreiss Jonathan Castrop Anika Galindo Warren Krieger-Coble Oceanna Causey Morgan Gallagher Kevin -

Family of Abraham

Family of Abraham Terah ? Haran Nahor Sarai - - - - - ABRAM - - - - - Hagar Lot Milcah Bethuel Ishmael (1) ISAAC (2) Daughter 1 Daughter 2 Ishmaelites (12 tribes / Arabs) Laban Rebekah Moabites Ammonites JACOB (2) Esau (1) Leah Rachel Edomites (+Zilpah) (+Bilhah) ISRAELITES Key: blue = men; red = women; (12 tribes / Jews) dashes = spouses; arrows = children Terah: from Ur of the Chaldeans; has 3 sons; wife not named (Gen 11:26-32; cf. Luke 3:34). Haran: dies in Ur before his father dies; wife not named; son Lot, daughters Milcah & Iscah (11:27-28). Nahor: marries Milcah, daughter of his brother Haran (11:29); have 8 sons, incl. Bethuel (22:20-24). Abram: main character of Gen 12–25; recipient of God’s promises; name changed to ABRAHAM (17:5); sons Ishmael (by Hagar) and Isaac (by Sarah); after Sarah’s death, takes another wife, Keturah, who has 6 sons (25:1-4), including Midian, ancestor of the Midianites (37:28-36). Lot: son of Haran, thus nephew of Abram, who takes care of him (11:27–14:16; 18:17–19:29); wife and two daughters never named; widowed daughters sleep with their father and bear sons, who become ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites (19:30-38). Sarai: Abram’s wife, thus Terah’s daughter-in-law (11:29-31); Abram also calls her his “sister,” which seems deceptive in one story (12:10-20); but in another story Abram insists she really is his half- sister (his father’s daughter by another wife; 20:1-18); originally childless, but in old age has a son, Isaac (16:1–21:7); name changed to SARAH (17:15); dies and is buried in Hebron (23:1-20). -

The Twelve Tribes of Israel by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D

The Twelve Tribes of Israel by Felix Just, S.J., Ph.D. In the Hebrew Bible (the Christian Old Testament), the Israelites are described as descendants of the twelve sons of Jacob (whose name was changed to Israel in Gen 32:28), the son of Isaac, the son of Abraham. The phrase "Twelve Tribes of Israel" (or simply "Twelve Tribes") sometimes occurs in the Bible (OT & NT) without any individual names being listed (Gen 49:28; Exod 24:4; 28:21; 39:14; Ezek 47:13; Matt 19:28; Luke 22:30; Acts 26:7; and Rev 21:12; cf. also "Twelve Tribes of the Dispersion" in James 1:1). More frequently, however, the names are explicitly mentioned. The Bible contains two dozen listings of the twelve sons of Jacob and/or tribes of Israel. Some of these are in very brief lists, while others are spread out over several paragraphs or chapters that discuss the distribution of the land or name certain representatives of each tribe, one after another. Surprisingly, however, each and every listing is slightly different from all the others, either in the order of the names mentioned or even in the specific names used (e.g., the two sons of Joseph are sometimes listed along with or instead of their father; and sometimes one or more names is omitted for various reasons). A few of the texts actually have more than 12 names! Upon closer analysis, one can discover several principles for the ordering and various reasons for the omission or substitution of some of the names, as explained in the notes below the following tables. -

God of Covenant: Exile & Reconciliation Session Six Gen 12

God of Covenant: Exile & Reconciliation Session Six Gen 12-50 How did the children of God come to live in the land of Egypt? Where did the 12 sons come from? • Jacob is defined by patterns of deception and he has twice deceived his brother, Esau. Self-reliance and going after with self-interest the good gifts God has already set aside for him. • Favoritism in the family. Jacob has picked up the same patterns from his home. He is still a very immature person. He knows God but doesn’t trust Him yet. More interested in the benefits of knowing God than God Himself Genesis 29-32 • Jacob remembers how his father met his mother. When Rachel appears, Jacob wants to get rid of the other men. He saw Rachel “and the sheep of Laban”; Then Jacob kissed Rachel & wept aloud. (overreacts) Similar language from Isaac/Rebecca. • Leah “wild cow” and Rachel “ewe lamb”; Leah is overlooked. Favoritism in this family! • Jacob is being deceived by his senses just like he deceived his father. • Leah didn’t have decision making to refuse. She probably had hope. Would have been hurt by Jacob & Laban. “and he loved Rachel more than Leah”. Jacob plays favorites too. • Gen 2 – marriage is between one man & one woman; one flesh. Jacob should have taken Leah and gone home. Polygamy in the Scriptures doesn’t mean God approves. It leads to enemies of Israel being born. God works through terrible to bring about His will. • Reuben “affliction”, Simeon “heard that I am hated”, Levi “husband will be attached”, Judah “this time I will praise the Lord”, • Rachel “envied her sister” “Give me children or I shall die!” She will die in childbirth. -

A Pilgrimage Through the Old Testament

A PILGRIMAGE THROUGH THE OLD TESTAMENT ** Year 2 of 3 ** Cold Harbor Road Church Of Christ Mechanicsville, Virginia Old Testament Curriculum TABLE OF CONTENTS Lesson 53: OLD WINESKINS/SUN STOOD STILL Joshua 8-10 .................................................................................................... 5 Lesson 54: JOSHUA CONQUERS NORTHERN CANAAN Joshua 11-15 .................................................................................................. 10 Lesson 55: DIVIDING THE LAND Joshua 16-22 .................................................................................................. 14 Lesson 56: JOSHUA’S LAST DAYS Joshua 23,24................................................................................................... 19 Lesson 57: WHEN JUDGES RULED Judges 1-3 ...................................................................................................... 23 Lesson 58: THE NORTHERN CONFLICT Judges 4,5 ...................................................................................................... 28 Lesson 59: GIDEON – MIGHTY MAN OF VALOUR Judges 6-8 ...................................................................................................... 33 Lesson 60: ABIMELECH AND JEPHTHAH Judges 9-12 .................................................................................................... 38 Lesson 61: SAMSON: GOD’S MIGHTY MAN OF STRENGTH Judges 13-16 .................................................................................................. 44 Lesson 62: LAWLESS TIMES Judges -

V‟ZOT HA‟BERACHAH – “And This Is the Blessing”

V‟ZOT HA‟BERACHAH – “And this is the Blessing” DEUTERONOMY (D‟VARIM 33:1 – 34:12) INTRODUCTION: 1. This portion describes what happened on the very last day of Moses‟s life. 2. Following in the tradition established by Jacob goes from tribe to tribe to blessing them. a. Like Jacob, Moses‟ blessing combines prophecy with the blessings. 3. Before leaving them, Moses gives a general blessing to the entire nation: “There is none like unto God, O Jeshurun, who rides on the heaven as your help.” 4. Because this is the last portion, this is the one read on Simchat Torah – rejoicing in the Torah – when the annual cycle is completed. a. Simchat Torah marks when the scroll is rolled back to the Beginning. b. Can‟t help but think of what Scripture has to say as all things are being restored: “Then the sky receded as a scroll when it is rolled up, and every mountain and island was moved out of its place.” - Revelation 6:14 CHAPTER 33: THE BLESSING 1. Verse 1: “And this is the blessing (v’zot ha’berachah).” a. The Song was an admonition describing punishments for disobedience. b. The Blessings describe Israel‟s ultimate destiny determined by God. 2. This is Moses‟ last act – to bless the ones who were, indirectly, responsible for his transgression which made it impossible for him to cross over into the land. a. When others might be tempted to curse, he blessed. b. He could do no less that Bila‟am who sought to curse but could only bless.