Scenic Design for the Musical Godspell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

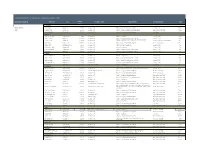

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Jack Kerouac's on the Road & How That Influenced the Road Movie

Sheldon 1 Matthew A. Sheldon Introduction to the Road Film Midterm Exam 12/15/12 Midterm Exam 1. One of the main films that focused it‟s themes on rebellious critique and conservative authority was Bonnie and Clyde. The film was less about historical accuracy and more a direct reflection of the late 1960‟s ideology with the rise of the Vietnam War, the assassination of President Kennedy and the horrific Charles Mansion murders. In David Laderman‟s essay he explains how the cultural roots of the road film seemed to step from three different genres which are the western, the gangster and the film noir which also are very similar to Jack Kerouac‟s 1955 novel On the Road. “All three of these genres predated On the Road, and Sal and Dean Affectionately invoke western and gangster films throughout. On the Road‟s basic themes and style also highlight the ideological contradiction between rebellion and tradition.” (3) Right in the opening shot of Bonnie and Clyde you can see a close-up of Bonnie Parker become bored and restless on her bed, wanting to escape the imprisonment of traditional lifestyle. When she catches Clyde trying to break into her mother‟s car, his dangerous character fascinates her and gives her an emotional sensual excitement of rebellion and risk that she never felt before. Clyde talks Bonnie into leaving with him not just because of the liberating crime life he is offering her but because he seems to be insightful in who she is as a person and what her Sheldon 2 needs and desires are. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

“Hello, Dolly!” the Tony Award-Winning Be

FOR RELEASE ON JULY 23, 2018 “The best show of the year. ‘Hello, Dolly!’ must not be missed.” NPR, David Richardson “This ‘Dolly!’ is classic Broadway at its best.” Entertainment Weekly, Maya Stanton “It is, in a word, perfection.” Time Out New York, Adam Feldman TONY AWARD®-WINNING BROADWAY LEGEND BETTY BUCKLEY STARS IN FIRST NATIONAL TOUR OF “HELLO, DOLLY!” THE TONY AWARD-WINNING BEST MUSICAL REVIVAL WILL BEGIN PERFORMANCES SEPTEMBER 30 AT PLAYHOUSE SQUARE SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE JULY 27 Cleveland, OH – The producers of HELLO, DOLLY!, the Tony Award-winning Best Musical Revival, and Playhouse Square announced today that single tickets for the National Tour starring Broadway legend Betty Buckley will go on sale Friday, July 27. Tickets will be available at the Playhouse Square Ticket Office (1519 Euclid Avenue in downtown Cleveland), by visiting playhousesquare.org, or by calling 216-241-6000. Group orders of 15 or more may be placed by calling 216-640-8600. HELLO, DOLLY! comes to Playhouse Square September 30 through October 21, 2018 as part of the KeyBank Broadway Series. Tony Award-winning Broadway legend Betty Buckley stars in HELLO, DOLLY! – the universally acclaimed smash that NPR calls “the best show of the year!” and the Los Angeles Times says “distills the mood-elevating properties of the American musical at its giddy best.” Winner of four Tony Awards including Best Musical Revival, director Jerry Zaks’ “gorgeous” new production (Vogue) is “making people crazy happy!” (The Washington Post). Breaking box office records week after week and receiving unanimous raves on Broadway, this HELLO, DOLLY! pays tribute to the original work of legendary director/choreographer Gower Champion – hailed both then and now as one of the greatest stagings in musical theater history. -

Pippin Buy Tickets

New York Subscribe to Time Out New York Search Things To Do Food & Drink Arts & Culture Film Music & Nightlife Shopping & Style City Guide Tickets & Offers Pippin Buy tickets Musicals Revival Music Box Theatre Until Sun Dec 22 Near Music Box Theatre Bars and Restaurants Shops pubs and cafés Photograph: Joan Marcus Paramount Bar and Grill Pippin Time Out rating: User ratings: Critics' pick Paramount Bar Rate this Comments 3 Time Out says Add + Marriott Marquis Hotel Thu Apr 25 2013 Like 406 Tweet 23 Theater review by Adam Feldman. Music Box Theatre (Broadway). 0 Book by Roger O. Hirson. Music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz. Dir. Rum House Diane Paulus. With Matthew James Thomas, Patina Miller, Rachel Bay Jones. 2hrs 30mins. One intermission. The Living Room at the W Ladies and gentlemen, step right up to the greatest show of the Broadway season: Diane Paulus’s sensational cirque-noir revival of Pippin. Here, in all its grand and dubious glory, is musical-theater showmanship at its best, 1001 others, see all a thrilling evening of art and craftiness spiked with ambivalence about the nature of enthrallment. Chet Walker’s dances, which retain the pelvic thrust of Bob Fosse’s original choreography, are a viciously precise mockery of showbiz bump and grind, enacted by a sexy, sinister, improbably limber ensemble (in skintight carnival gear and medieval costumery). Circus elements created by Gypsy Snider—acrobatics, aerialism, contortionism, juggling, hula hoops—build momentum toward what the ringmaster assures us is “a climax you will remember for the rest of your lives.” That just might be true. -

42Nd Street Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 5-25-1996 42nd Street Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "42nd Street" (1996). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 82. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/82 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 42ND STREET Saturday, May 25 IP Ml" :• i fi THE CENTER FOR ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY AT GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY The Troika Organization, Music Theatre Associates, The A.C. Company, Inc., Nicholas Hovvey, Dallett Norris, Thomas J. Lydon, and Stephen B. Kane present Music by Lyrics by HARRY WARREN AL DUBIN Book by MICHAEL STEWART & MARK BRAMBLE Based on the novel by BRADFORD ROPES Original Direction and Dances by Originally Produced on Broadway by GOWER CHAMPION DAVID MERRICK Featuring ROBERT SHERIDAN REBECCA CHRISTINE KUPKA MICHELLE FELTEN MARC KESSLER KATHY HALENDA CHRISTOPHER DAUPHINEE NATALIE SLIPKO BRIANW.WEST SHAWN EMAMJOMEH MICHAEL SHILES Scenic Design by Costume Design by Lighting Design by JAMES KRONZER NANZI ADZIMA MARY JO DONDLINGER Sound Design by Hair and Makeup Design by Asst. Director/Choreographer KEVIN HIGLEY JOHN JACK CURTIN LeANNE SCHINDLER Orchestral & Vocal Arranger Musical Director & Conductor STEPHEN M. BISHOP HAMPTON F. KING, JR. -

Second Chances Holy Spirit Touch My Lips, Open Our Hearts, And

Sermon for Date Church of the Holy Comforter Joseph Klenzmann Second Chances Holy Spirit Touch My Lips, Open Our Hearts, And Transform Our Lives. Amen Well it is a new season, a new year in the life of the church. Advent, a season that is worshiped in a more solemn, quiet, less festive manor than other seasons in the church. There is no joyous Christmas music during the four weeks of advent. Advent is a time where Christians around the world commemorate the first coming of the messiah and our ardent anticipation of Christ’s second coming as Judge. Actually, the word Advent comes from the Latin word adventus which means “coming” or “Arrival”. Advent is a time to prepare for his coming. A time to look at our lives, a second chance to be the kind of person the lord knows we can be. The bible stories of John the Baptist are stories of preparation and transition. John has come to “Make Straight The Path”. To quote one of my favorite songs from the play Godspell “Prepare Ye The Way Of The Lord”. That is actually Mark chapter 1 verse 3, but I really liked Godspell. John the Baptist is a transition from the PROMISE of the Old Testament to the New Testament REALITY of Christ in the flesh. In Advent each year, we remember that reality and the new promise of his second coming. In Jeremiah, we heard God tell Jeremiah: “I Will Fulfill The Promise I Made To The House Of Israel And The House Of Judah” we also heard that god will have “A Righteous Branch Spring Up From David” This is the Messianic message told throughout the Old Testament, told by the Patriarchs and the Profits. -

The Tony Award-Winning Best Musical Revival

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Rachel Bliss, Starlight Theatre [email protected] 816-997-1151-office 785-259-3039-cell The Tony Award-Winning Best Musical Revival Will Begin Performances September 25 at Starlight Theatre “THE BEST SHOW OF THE “THIS ‘DOLLY!’ IS CLASSIC “IT IS, IN A WORD, YEAR. ‘HELLO, DOLLY!’ BROADWAY AT ITS BEST.” PERFECTION.” MUST NOT BE MISSED.” - ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY, - TIME OUT NEW YORK, - NPR, DAVID RICHARDSON MAYA STANTON ADAM FELDMAN KANSAS CITY, Mo. – The producers of HELLO, DOLLY!, the Tony Award-winning Best Musical Revival, and Starlight Theatre are excited to announce that single tickets for the National Tour starring Carolee Carmello are on sale now. Tickets are available at the Starlight Theatre box office (4700 Starlight Road, Kansas City, MO, 64132), by visiting kcstarlight.com, or by calling 816-363-STAR (7827). Group orders of 10 or more may be placed by calling 816-997-1137. “This production of Hello, Dolly! is bigger and better than it’s ever been,” Rich Baker, President and CEO of Starlight, said. “This tour is everything that I love about Broadway—and spares no extravagance. It celebrates the iconic moments of this larger-than-life musical with incredible sets and costumes, phenomenal dancing, and big-talent that has what it takes to champion these iconic roles. What could be better than Hello, Dolly! to complete our 2019 AdventHealth Broadway Series?” Winner of four Tony Awards including Best Musical Revival, HELLO, DOLLY! is the universally acclaimed smash that NPR calls “the best show of the year!” and the Los Angeles Times says “distills the mood-elevating properties of the American musical at its giddy best.” Director Jerry Zaks’ “gorgeous” new production (Vogue) is “making people crazy happy!” (The Washington Post). -

News Release for Immediate

NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: April 30, 2020 OFF-BROADWAY CAST OF “THE WHITE CHIP”, SEAN DANIELS’ CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED PLAY ABOUT HIS UNUSUAL PATH TO SOBRIETY, WILL DO A LIVE ONLINE READING AS A BENEFIT Performance Will Benefit The Voices Project and Arizona Theatre Company and is dedicated to Terrence McNally. In line with Arizona Theatre Company’s (ATC) ongoing commitment to bringing diverse creative content to audiences online, the original Off-Broadway cast of The White Chip will perform a live reading of Artistic Director Sean Daniels’ play about his unusual path to sobriety as a fundraiser for The Voices Project, a grassroots recovery advocacy organization, and Arizona Theatre Company. The benefit performance will be broadcast live at 5 p.m. (Pacific Time) / 8 p.m. (Eastern Time), Monday, May 11 simultaneously on Arizona Theatre Company’s Facebook page (@ArizonaTheatreCompany) and YouTube channel. The performance is free, but viewers are welcome to donate what they can. The performance will then be available for four days afterwards through ATC’s website and YouTube channel. All donations will be divided equally between the two organizations. A New York Times Critics’ Pick, The White Chip was last staged Off-Broadway at 59E59 Theaters in New York City, from Oct. 4 - 26, 2019. Tony Award-nominated director Sheryl Kaller, Tony Award-winning sound designer Leon Rothenberg and the original Off- Broadway cast (Joe Tapper, Genesis Oliver, Finnerty Steeves) will return for the reading. The Off-Broadway production was co-produced with Tony Award-winning producers Tom Kirdahy (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown) and Hunter Arnold (Little Shop of Horrors, Hadestown). -

American Road Movies of the 1960S, 1970S, and 1990S

Identity and Marginality on the Road: American Road Movies of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies. © Alan Hui-Bon-Hoa 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Abrégé …………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Acknowledgements …..………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Chapter One: The Founding of the Contemporary Road Rebel …...………………………...… 23 Chapter Two: Cynicism on the Road …………………………………………………………... 41 Chapter Three: The Minority Road Movie …………………………………………………….. 62 Chapter Four: New Directions …………………………………………………………………. 84 Works Cited …………………………………………………………………………………..... 90 Filmography ……………………………………………………………………………………. 93 2 Abstract This thesis examines two key periods in the American road movie genre with a particular emphasis on formations of identity as they are articulated through themes of marginality, freedom, and rebellion. The first period, what I term the "founding" period of the road movie genre, includes six films of the 1960s and 1970s: Arthur Penn's Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider (1969), Francis Ford Coppola's The Rain People (1969), Monte Hellman's Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Richard Sarafian's Vanishing Point (1971), and Joseph Strick's Road Movie (1974). The second period of the genre, what I identify as that -

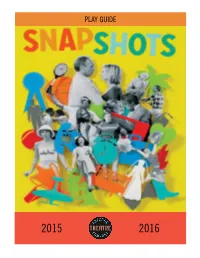

SNP Play Guide R2

PLAY GUIDE 2015 2016 About ATC .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction to the Play ............................................................................................................................... 2 Meet the Creators ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Meet the Characters .................................................................................................................................... 3 Songs and Sources ...................................................................................................................................... 4 A New Musical Genre ................................................................................................................................... 7 The History of Photography .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Science of Memory ............................................................................................................................... 10 Glossary ..................................................................................................................................................... 13 Discussion Questions and Activities ...........................................................................................................17 -

Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 3 Issue 2 October 1999 Article 2 October 1999 Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Mark Goodacre University of Birmingham, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Goodacre, Mark (1999) "Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 3 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol3/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Do You Think You're What They Say You Are? Reflections on Jesus Christ Superstar Abstract Jesus Christ Superstar (dir. Norman Jewison, 1973) is a hybrid which, though influenced yb Jesus films, also transcends them. Its rock opera format and its focus on Holy Week make it congenial to the adaptation of the Gospels and its characterization of a plausible, non-stereotypical Jesus capable of change sets it apart from the traditional films and aligns it with The Last Temptation of Christ and Jesus of Montreal. It uses its depiction of Jesus as a means not of reverence but of interrogation, asking him questions by placing him in a context full of overtones of the culture of the early 1970s, English-speaking West, attempting to understand him by converting him into a pop-idol, with adoring groupies among whom Jesus struggles, out of context, in an alien culture that ultimately crushes him, crucifies him and leaves him behind.