(R)Evolution in Consumption, Community, Urbanism, and Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

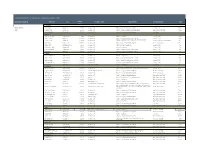

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Scenic Design for the Musical Godspell

Scenic design for the musical Godspell Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Sugarbaker Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2009 Master’s Examination Committee: Professor Dan Gray, M.F.A. Advisor Professor Mandy Fox, M.F.A. Professor Kristine Kearney, M.F.A. Copyright by Sarah Sugarbaker 2009 Abstract In April of 2009 the Ohio State University Theatre Department produced Godspell, a musical originally conceived by John‐Michael Tebelak with music by Stephen Schwartz. This production was built and technically rehearsed in the Thurber Theatre, and then moved to the Southern Theatre in downtown Columbus, OH. As the scenic designer of this production I developed an environment in which the actors and director created their presentation of the text. Briefly, the director’s concept (Appendix A) for this production was to find a way to make the production relevant to the local population. Godspell centers around the creation and support of a community, so by choosing to reference the City Center Mall, an empty shopping center in downtown Columbus, the need for making a change as a community was emphasized. This environment consisted of three large walls that resembled an obscured version of the Columbus skyline, inspired by advertisements within the shopping center. Each wall had enlarged newspapers that could be seen under a paint treatment of vibrant colors. The headlines on these papers referenced articles that the local paper has written about the situation at the shopping center, therefore making the connection more clear. -

Maddie's Journey

2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF PHILANTHROPY Maddie’s Journey FROM THE DAY HER SURVIVAL WAS IN QUESTION, TO THE DAY WE SPENT WITH HER AT PHILADELPHIA’s independence hall. NAtionwide children’s hospitAL Twenty weeks before the day she was born, Maddie’s journey took an unexpected turn. 2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF PHILANTHROPY At 20 weeks into Emile’s second pregnancy, when Ten days after Maddie was born, cardiothoracic a routine ultrasound revealed a birth defect called surgeon, Dr. Mark Galantowicz and The Heart Dandy Walker, Emile and Chris Sower knew there Center team began the open-heart procedure at would be anxious days ahead. What the Sowers – 6 a.m. Seven hours later, Dr. Galantowicz emerged and doctors – didn’t know was that this birth defect from the operating room and told Maddie’s parents would be the least of Maddie’s medical challenges. that the operation was a success. One hurdle cleared: more to follow. For the next 20 weeks, the pregnancy went as planned and Maddie was born near her original Two days after successful heart surgery, Maddie due date. Then, during a routine examination, was still unable to keep food down. While it is not physicians at the birth hospital detected a uncommon for patients to experience difficulty heart arrhythmia. As a precaution, they made taking nourishment following heart surgery, her arrangements for Maddie to be transferred to parents grew concerned. Physicians ordered a Nationwide Children’s Hospital. CT scan and they discovered a bowel obstruction. Yes, Maddie was rushed into surgery again. But Upon her arrival, neonatologists examined Maddie 30 minutes into the operation, the surgeon walked and discovered a serious heart condition. -

Bulletin 12/09/06 (Pdf)

Columbus City Bulletin Bulletin #49 December 9, 2006 Proceedings of City Council Saturday, December 9, 2006 SIGNING OF LEGISLATION (With the exception of Ordinances 1920-2006 and 1926-2006 which were signed by Council President Pro-Tem, Michael C. Mentel on the night of the Council Meeting, Monday December 4, 2006; and by Mayor, Michael B. Coleman on Wednesday, December 6, 2006 all other legislation listed in this bulletin was signed by Council President Matthew D. Habash , on the night of the Council meeting, Monday, December 4, 2006; Mayor, Michael B. Coleman on Wednesday, December 6, 2006 and attested by the City Clerk, Andrea Blevins prior to Bulletin publishing.) The City Bulletin Official Publication of the City of Columbus Published weekly under authority of the City Charter and direction of the City Clerk. The Office of Publication is the City Clerk’s Office, 90 W. Broad Street, Columbus, Ohio 43215, 614-645-7380. The City Bulletin contains the official report of the proceedings of Council. The Bulletin also contains all ordinances and resolutions acted upon by council, civil service notices and announcements of examinations, advertisements for bids and requests for professional services, public notices; and details pertaining to official actions of all city departments. If noted within ordinance text, supplemental and support documents are available upon request to the City Clerk’s Office. Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 12/09/06) 2 of 330 Council Journal (minutes) Columbus City Bulletin (Publish Date 12/09/06) 4 of 330 Office of City Clerk City of Columbus 90 West Broad Street Columbus OH Journal - Final 43215-9015 columbuscitycouncil.org Columbus City Council ELECTRONIC READING OF MEETING DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE DURING COUNCIL OFFICE HOURS. -

What Is Landscape Architecture?

What is Landscape Architecture? Landscape architecture encompasses the analysis, planning, design, management, and stewardship of the natural and built environments. Types of projects include: residential; parks and recreation; monuments; urban design; streetscapes and public spaces; transportation corridors and facilities; gardens and arboreta; security design; hospitality and resorts; institutional; academic campuses; therapeutic gardens; historic preservation and restoration; reclamation; conservation; corporate and commercial; landscape art and earth sculpture; interior landscapes; and more. Landscape architects have advanced education and professional training and are licensed in 49 states. O H I O C H A P T E R Award Submittals Table of Contents Introduction ___________________________________________2 2008/2009 OCASLA Executive Committee Officers ____________ 4 Letter from the Chapter Trustee __________________________ 5 Award Categories _____________________________________ 6 Award Levels / Award Jurors _____________________________ 7 Design - Not Constructed _________________________________9 Honor Award Winner - Housing Bank for Trade & Finance - nbbj ___________________ 10 Honor Award Winner - Cleveland State University Euclid Ribbon - nbbj ______________ 12 John P. Parker Community Master Plan - meisner & associates _____ 14 Miamisburg Riverfront Masterplan - msi ____________________ 15 Shanghai Nan Jiao - pod design ____________________________ 16 2 Columbus City Center Urban Design - msi ___________________ 17 The Plaza at -

Solid Waste Management Plan

SOLID WASTE AUTHORITY OF CENTRAL OHIO 2018 – 2032 Solid Waste Management Plan Approved February 28th, 2018 Prepared by: Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio Ratified Plan, February 28, 2018 Table of Contents CHAPTERS Chapter 1 – Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1‐1 Chapter 2 – District Profile ..................................................................................................... 2‐1 Chapter 3 – Waste Generation .............................................................................................. 3‐1 Chapter 4 – Waste Management ........................................................................................... 4‐1 Chapter 5 – Waste Reduction and Recycling ......................................................................... 5‐1 Chapter 6 – Budget ................................................................................................................ 6‐1 APPENDICES Appendix A – Reference Year, Planning Period, Goal Statement, Material Change in Circumstances, Explanations of Differences in Data ............................................................. A‐1 Appendix B – Recycling Infrastructure Inventory .................................................................. B‐1 Appendix C – Population Data ............................................................................................... C‐1 Appendix D – Disposal Data .................................................................................................. -

Schools Business Homes Recreation Columbus Monthly Advertising

UPPER A Schools Business Homes Recreation Columbus Monthly Advertising Section GOOD THINGS HAPPEN WHEN You MAKE THE RIGHT DRIVE. Your favorite and the unique stores. Men's, women's and children's fashions and accessories. Home furnishings, electronics, cards and books. Toys, pets. Gifts and more gifts. Restaurants. Two of Columbus' most popular restaurants, and a food court teeming with choices. And services. Styling, printing, tailoring, repairing. \\a ASHOUJOfHBNDS *N £•!>** LARSON „ / s()r * ^/%iK •D s Sh </ Bombay ^ < N Com?' Lane Avenue. A Spectacular Collection of Over 90 Stores. Including Banana Republic, Dockers Shop, Little Between Route 315 and Route 33 Professor Book Company, MicroCenter, The on Lnae Avenue in Upper Arlington Original Levi's Store. Talbots, and China Dynasty 614/481-8341 and Peasant on the Lane restaurants. Monday - Saturday 10 to 9 • Sunday 12 to 5 Preserving the best, Renewing the rest ride. Spirit. Opportunity. Those are more than just the words on Up per Arlington's new logo. They represent the way we feel about our Pcommunity's past, present and future. Those of us fortunate enough to live or work in Upper Arlington take pride in a city that has maintained the highest standards of excellence for more than 75 years. We're proud of our homes, proud of our schools, proud of our recreational and cultural facilities. But most of all we're proud of our people, the 35,000 citizens who make Upper Arlington what it is. They give us the community spirit that bricks and mortar alone never can provide. Like every community, Upper Arlington is changing. -

Napa Auto Parts 4020 E Main Street | Columbus, Oh 43213

CAPITAL MARKETS | RETAIL NAPA AUTO PARTS 4020 E MAIN STREET | COLUMBUS, OH 43213 OFFERING MEMORANDUM NAPA AUTO PARTS | COLUMBUS, OH AFFILIATED BUSINESS DISCLOSURE AND CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT CBRE, Inc. operates within a global family of companies with many This Memorandum contains select information pertaining to the Property subsidiaries and related entities (each an “Affiliate”) engaging in a and the Owner, and does not purport to be all-inclusive or contain all or broad range of commercial real estate businesses including, but not part of the information which prospective investors may require to evaluate limited to, brokerage services, property and facilities management, a purchase of the Property. The information contained in this Memorandum valuation, investment fund management and development. At times has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but has not different Affiliates, including CBRE Global Investors, Inc. or Trammell Crow been verified for accuracy, completeness, or fitness for any particular Company, may have or represent clients who have competing interests purpose. All information is presented “as is” without representation or in the same transaction. For example, Affiliates or their clients may have warranty of any kind. Such information includes estimates based on or express an interest in the property described in this Memorandum forward-looking assumptions relating to the general economy, market (the “Property”), and may be the successful bidder for the Property. Your conditions, competition and other factors which are subject to uncertainty receipt of this Memorandum constitutes your acknowledgment of that and may not represent the current or future performance of the Property. possibility and your agreement that neither CBRE, Inc. -

2007 Annual Report 2007 Annual Report

2007 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ANNUAL | NEXT PAGE » 2007 ANNUAL REPORT 2007 HIGHLIGHTS Expanding our reach into the community STRATEGIC THINKING LIVE/WORK SPACES FOR ARTISTS In July, GCAC released a five-year strategic plan GCAC and Columbus City Council collaborated that gives us a road map for the organization to bring Artspace Projects, Inc., a national through the city’s bicentennial in 2012. Along with organization dedicated to affordable live/work its strategic plan, GCAC released a new logo and spaces for artists, to Columbus to conduct a brand. feasibility study for a potential space in the area. Since the August visit, Artspace has determined REPORT 2007 ANNUAL that Columbus is an excellent market for a 2007 GRANTS potential live/work location. This March, GCAC, GCAC granted $2.2 million in Operating Support Artspace and our partners – the City of Columbus, grants and $450,602 in Project Support grants to JPMorgan Chase, the Columbus Downtown 88 organizations and projects in 2007. Development Corporation and Capitol South – will work with the community to begin the process of determining where that building should be and FOCUSING ON INDIVIDUAL ARTISTS what it should look like. In November, GCAC conducted four artist roundtable meetings to get feedback on our plans EDUcating CHILDREN to expand services to individual artists. In January, we began OPPArt (Opportunities for Artists), a More than 70,000 students and adults participated series of workshops, networking events and social in our Artists-in-Schools or Children of the Future opportunities for artists in the community. programs. NEW EDUcatiONAL PARTNERSHIP THE COLUMBUS ARTS FESTIVAL Presented by Chase In January, we received funding from the Franklin County Board of Commissioners for a cutting- More than 400,000 people gathered along the edge educational initiative called Art in the House riverfront for the 2007 Columbus Arts Festival & TRANSIT ARTS that will focus on out-of-school presented by Chase. -

Survival Guide 2005 2005 年交換學生生活指南

Survival Guide 2005 2005 年交換學生生活指南 謝志偉、王奐之、沈榮慶、楊智雯、林彥翰 目錄 一、生活地理環境簡介……………………………………………………………………………………………...2 (1). Columbus, Ohio……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….2 (2). Ohio State University (OSU)……………………………………………………………………………………………………2 (3). OSU Hospital……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 二、行前準備………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 (1). 聯絡 Dr. Harrison Weed……………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 (2). 選課………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 (3). 行李確認……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 (4). 住宿………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 三、初到…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 (1). 接機………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 (2). 抵達校園報到…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 四、生活 ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 (1). 食……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 (2). 住……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………12 (3). 行……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………15 (4). 衣……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………19 (5). 娛樂………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 (6). 其他………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..24 附錄……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….27 1 一、生活地理環境簡介: (1). Columbus, Ohio Ohio位於美國東北部,地處北美五大湖的 伊利湖(Lake Erie)南方,於1803年成為美國 第 17 個州。相鄰各州包括北方的密西根州 (Michigan),西方的印第安那州(Indiana), 南方的肯塔基州(Kentucky),東南方的西維吉 尼亞州(West Virginia),及東方的賓夕法尼亞 州( Pennsylvania)。州內生長著為數眾多的橡 Ohio State House 樹( Buckeye,因其果實外型酷似雄鹿的眼睛而 得名),因此又被稱為「The Buckeye State」;OSU的學生證也因此而取名「Buck -

RHEOLOGY BULLETIN Published by the Society of Rheology

RHEOLOGY BULLETIN Published by The Society of Rheology TT Ct V Tili Vol. 66 No. 2 July 1997 THE SOCIETY OF RHEOLOGY 69th ANNUAL MEETING EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE -1995-97 COLUMBUS. OH OCTOBER 19 - 23,1997 President Kurt F. Wissbrun Vice President Ronald G. Larson The annual meeting of the Society of Rheology will be held Secretary Andrew M. Kraynik at the Hyatt on Capital Square Hotel in Columbus, Ohio. Treasurer Edward A. Collins Details of the technical program may be found on the Society's Editor Morton M. Denn web page at http://www.umecheme.maine.edu/sor/ while other Past President Robert C. Armstrong details are given inside this issue of Rheology Bulletin. Also Members-at-Large Gerald G. Fuller enclosed are the meeting registration and hotel reservation A. Jeffrey Giacomin forms. The meeting organizers are: COMMITTEES Technical Program Chair: Robert L. Powell Dept. of Chemical Engineering & Materials Science Membership: Education: University of California at Davis A.J. Giacomin, chair PE. Clark, chair S. Drappel D.G. Baird Davis, CA 95616 P. Moldenaers E.A. Collins (916) 752-8779; Fax: (916)752-1031 W.E. VanArsdale S. Muller e-mail: [email protected] L.E. Wedgewood W. Prest Local Arrangements: W.E. VanArsdale R. Webber Jacques L. Zakin, Chair Kurt Koelling, Co-Chair Stephen Bechtel Bingham Award: Meetings Policy: Robert Brodkey R.G. Larson, chair E.S.G. Shaqfeh, chair Department of Chemical Engineering G.G. Fuller G.C. Berry Ohio State University A.J. Giacomin A. Chow Columbus, OH 43210 A.M. Kraynik D.F. James R.L. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize m aterials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812281 Private planning for economic development: Local business coalitions in Columbus, Ohio: 1858—1980 Mair, Andrew, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy.