The Process and Practice of Downtown Revitalization in Columbus, Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

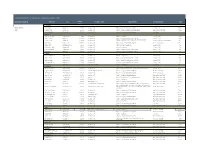

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team

Track Record of Prior Experience of the Senior Cobalt Team Dedicated Executives PROPERTY City Square Property Type Responsibility Company/Client Term Feet COLORADO Richard Taylor Aurora Mall Aurora, CO 1,250,000 Suburban Mall Property Management - New Development DeBartolo Corp 7 Years CEO Westland Center Denver, CO 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and $30 million Disposition May Centers/ Centermark 9 Years North Valley Mall Denver, CO 700,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment First Union 3 Years FLORIDA Tyrone Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 1,180,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 3 Years University Mall Tampa, FL 1,300,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 2 Years Property Management, Asset Management, New Development Altamonte Mall Orlando, FL 1,200,000 Suburban Mall DeBartolo Corp and O'Connor Group 1 Year and $125 million Disposition Edison Mall Ft Meyers, FL 1,000,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and Redevelopment The O'Connor Group 9 Years Volusia Mall Daytona Beach ,FL 950,000 Suburban Mall Property and Asset Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year DeSoto Square Mall Bradenton, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management DeBartolo Corp 1 Year Pinellas Square Mall St Petersburg, FL 800,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year EastLake Mall Tampa, FL 850,000 Suburban Mall Property Management and New Development DeBartolo Corp 1 Year INDIANA Lafayette Square Mall Indianapolis, IN 1,100,000 Suburban Mall Property Management -

Columbus Hot Spots

Daytime columbus hot spots FEED YOUR NEED FOR CAFFEINE Stauf’s Coffee Franklinton Fox in the Roasters 421 W. State St. Snow Café (inside the staufs.com Idea Foundry) 1031 N. 4th St. 614-372-5677 Discovery District 614-549-0088 foxinthesnow.com 350 Mt. Vernon Ave. 614-549-0039 Grandview The Roosevelt Brioso Coffee 1277 Grandview Ave. Coffeehouse 329 E. Long St. 614-486-4861 300 E. Long St. 614-754-9511 German Village 614-670-5228 briosocoffee.com 627 S. 3rd St. rooseveltcoffee.org 614-221-1563 more at cbuscoffee.com North Market 59 Spruce St. One Line Coffee 614-456-7685 745 N. High St. 614-564-9852 continued to the right onelinecoffee.com BRUNCH THE DAY AWAY Katalina’s Hang Over Easy Union Cafe 1105 Pennsylvania 1646 Neil Ave. 782 N. High St. Ave. 614-586-0070 614-421-2233 614-294-2233 hangovereasycolum- facebook.com/ katalinascafe.com bus.com unioncafe Skillet Harvey & Ed’s 410 E. Whittier St. 698 N. High St. 614-443-2266 614-641-4040 skilletruf.com harveyandeds.com FOODIE FAVORITES North Market The Pearl Jeni’s Splendid 59 Spruce St. 641 N. High St. Ice Creams 614-463-9664 614-227-0151 various locations, northmarket.com thepearlcolumbus.com see jenis.com for more information Katzinger’s Deli Schmidt’s 475 S. 3rd St. Sausage Haus 614-228-3354 240 E. Kossuth St. katzingers.com 614-444-6808 schmidthaus.com BACK TO NATURE Goodale Park Schiller Park Topiary Park 120 W. Goodale St. 1069 Jaeger St. 480 E. Town St. 614-645-3300 614-645-3156 614-645-0197 columbus.gov/ germanvillage.com topiarypark.org recreationandparks Scioto Mile Grange Insurance 233 S. -

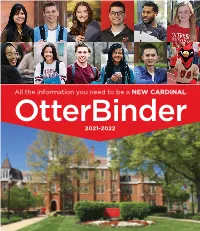

All the Information You Need to Be a NEW CARDINAL. Otterbinder 2021-2022 Otterbinder Checklist

All the information you need to be a NEW CARDINAL. OtterBinder 2021-2022 OtterBinder Checklist o UPON RECEIPT OF THE OTTERBINDER – Activate your Otterbein email and network account (see page 48) MAY o Early May – Course Registration Survey emailed to student’s Otterbein email account. The Course Registration Survey is due within two weeks of receiving it. o May 15 – Registration deadline for Summer Orientation, Advising and Registration (S.O.A.R.).* Online request form at www.otterbein.edu/SOARform. JUNE o If you are attending the June 17* or June 19* Orientation, make sure your Course Registration Survey is completed. If necessary, take the Modern Language Placement Exam at least two weeks in advance of Orientation. o Early June – A link to the on-line Education Module for New Students, focused on choices related to alcohol/drugs and sexual misconduct, will be sent to student’s Otterbein email account. o June 1 – All Student Address, Housing, Commuter and Housing Accommodation forms are due. • Student Housing Request Form • Residence Hall Room and Board Plan Agreement • Student Address Information Form • Application for Commuter Status and Parent Verification Form • Student Health Form • Housing Accommodation Requests for diagnosed disabilities (including requests for air conditioning) o June 15 – • All students accept desired loan amounts online through Banner. • First-time borrowers complete Direct Loan Promissory Notes and Entrance Counseling. • Complete Parent PLUS application and Private Loans for students and parents. o June 17 – New student S.O.A.R. session (Orientation)*. o June 19 – New student S.O.A.R. session (Orientation)*. JULY o If you are attending the July 9 Orientation*, make sure your Course Registration Survey is completed. -

Environmental Justice Technical Analysis

Appendix 3: Environmental Justice Technical Analysis April 27, 2015 This report was prepared by the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission (MORPC), 111 Liberty St., Columbus, OH 43215, 614-228-2663, with funding from the Federal Highway Administration, Federal Transit Administration, Ohio Department of Transportation, and Delaware, Fairfield, Franklin, and Licking counties. The contents of this report reflect the views of MORPC, which is solely responsible for the information presented herein. In accordance with requirements of the U.S. Department of Transportation, MORPC does not discriminate on the basis of age, race, color, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, familial status, ancestry, military status, religion or disability in programs, services or in employment. Information on non-discrimination and related MORPC policies and procedures is available at www.morpc.org under About MORPC/Policies. Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION TO ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE ...................................... 2 A. Definition of Environmental Justice ................................................................................... 2 B. Regulatory Framework for Environmental Justice ............................................................ 2 C. MORPC’s Approach to Environmental Justice .................................................................. 3 II. DEMOGRAPHICS ..................................................................................... 4 A. Data Set Review ................................................................................................................ -

Course Descriptions Course Descriptions - 155

Course Descriptions SANTA MONICA COLLEGE CATALOG 2020–2021 155 How to Read the Course Descriptions Course Number and Name Classes that must be completed prior to taking this course. FILM 33, Making the Short Film 3 units Units of Credit Transfer: UC, CSU • Prerequisite: Film Studies 32. Classes that must • Corequisite: Film Studies 33L. be taken in the In this course, students go through the process of making same semester as a short narrative film together, emulating a professional this course. working environment. Supervised by their instructor, stu- dents develop, pre-produce, rehearse, shoot, and edit scenes from an original screenplay that is filmed in its C-ID is a course entirety in the lab component course (Film 33L) at the end numbering system of the semester. used statewide for lower-division, trans- ferable courses that Course are part of the AA-T or Transferability GEOG 1, Physical Geography 3 units AS-T degree. Transfer: UC*, CSU C-ID: GEOG 110. IGETC stands for IGETC AREA 5 (Physical Sciences, non-lab) Course Descriptions Recommended class Intersegmental • Prerequisite: None. to be completed General Education • Skills Advisory: Eligibility for English 1. Transfer Curriculum. before taking this *Maximum credit allowed for Geography 1 and 5 is one course. This is the most course (4 units). common method of This course surveys the distribution and relationships of satisfying a particular environmental elements in our atmosphere, lithosphere, UC and CSU general hydrosphere and biosphere, including weather, climate, Brief Course education transfer water resources, landforms, soils, natural vegetation, and requirement category. Description wildlife. Focus is on the systems and cycles of our natural world, including the effects of the sun and moon on envi- ronmental processes, and the roles played by humans. -

The Schulte Family in Alpine, California

THE SCHULTE FAMILY IN ALPINE, CALIFORNIA The two things that have led to my connection and fascination with Alpine are my visits with my grandmother, Marguerite (Borden) Head or “Zuella”, and the Foss family in the 1950s, and the exquisite art work of Leonard Lester (see separate articles titled The Marguerite (Borden) and Robert Head Family of Alpine” and “Leonard Lester – Artist”). Most of the information on the Schulte family presented here is from 1) conversations with my father, Claude H. Schulte; 2) my grandfather, Christopher Henry Schulte, whose personal history was typed by his daughter, Ruth in 1942; and 3) supplemented by interviews with and records kept by my Aunt Ruth Schulte, including her mother’s diary. Kenneth Claude Schulte – December 2009 Christopher Henry Schulte, who immigrated to the United States in 1889, was born in Twistringen, Germany on 21 Dec 1874 and died 1 May 1954 in Lemon Grove, San Diego Co., California. In Arkansas he was married on 28 Jul 1901 to Flora Birdie Lee, born 16 Oct. 1883, Patmos, Hempstead Co., Arkansas and died 11 Jul 1938, Alpine, San Diego Co., California. Henry and Birdie had eight children: 1. Carl Lee Schulte b. 14 Oct 1902 Arkansas 2. Lois Birdie Schulte b. 07 Jun 1904 Arkansas 3. Otto Albert Schulte b. 29 May 1908 Arkansas 4. Lucille Schulte b. 02 Aug 1910 California 5. Claude Henry (C.H.) Schulte b. 19 Aug 1912 Arkansas 6. Harold Christopher Schulte b. 21 Mar 1915 California 7. Ruth Peace Schulte b. 10 Nov 1918 California 8. William Edward Schulte b. -

Rtd Light Rail Design Criteria

RTD LIGHT RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA Regional Transportation District November 2005 Prepared by the Engineering Division of the Regional Transportation District Regional Transportation District 1600 Blake Street Denver, Colorado 80202-1399 303.628.9000 RTD-Denver.com November 28, 2005 The RTD Light Rail Design Criteria Manual has been developed as a set of general guidelines as well as providing specific criteria to be employed in the preparation and implementation of the planning, design and construction of new light rail corridors and the extension of existing corridors. This 2005 issue of the RTD Light Rail Design Criteria Manual was developed to remain in compliance with accepted practices with regard to safety and compatibility with RTD's existing system and the intended future systems that will be constructed by RTD. The manual reflects the most current accepted practices and applicable codes in use by the industry. The intent of this manual is to establish general criteria to be used in the planning and design process. However, deviations from these accepted criteria may be required in specific instances. Any such deviations from these accepted criteria must be approved by the RTD's Executive Safety & Security Committee. Coordination with local agencies and jurisdictions is still required for the determination and approval for fire protection, life safety, and security measures that will be implemented as part of the planning and design of the light rail system. Conflicting information or directives between the criteria set forth in this manual shall be brought to the attention of RTD and will be addressed and resolved between RTD and the local agencies andlor jurisdictions. -

Scenic Design for the Musical Godspell

Scenic design for the musical Godspell Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sarah Sugarbaker Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2009 Master’s Examination Committee: Professor Dan Gray, M.F.A. Advisor Professor Mandy Fox, M.F.A. Professor Kristine Kearney, M.F.A. Copyright by Sarah Sugarbaker 2009 Abstract In April of 2009 the Ohio State University Theatre Department produced Godspell, a musical originally conceived by John‐Michael Tebelak with music by Stephen Schwartz. This production was built and technically rehearsed in the Thurber Theatre, and then moved to the Southern Theatre in downtown Columbus, OH. As the scenic designer of this production I developed an environment in which the actors and director created their presentation of the text. Briefly, the director’s concept (Appendix A) for this production was to find a way to make the production relevant to the local population. Godspell centers around the creation and support of a community, so by choosing to reference the City Center Mall, an empty shopping center in downtown Columbus, the need for making a change as a community was emphasized. This environment consisted of three large walls that resembled an obscured version of the Columbus skyline, inspired by advertisements within the shopping center. Each wall had enlarged newspapers that could be seen under a paint treatment of vibrant colors. The headlines on these papers referenced articles that the local paper has written about the situation at the shopping center, therefore making the connection more clear. -

SEPTEMBER 17, 2017 24TH WEEK of ORDINARY TIME VOLUME 66:44 DIOCESE of COLUMBUS a Journal of Catholic Life in Ohio

CATHOLIC SEPTEMBER 17, 2017 24TH WEEK OF ORDINARY TIME VOLUME 66:44 DIOCESE OF COLUMBUS A journal of Catholic life in Ohio PONTIFICAL COLLEGE JOSEPHINUM SENDS PRIESTS ACROSS THE NATION 2017 CATHOLIC COLLEGES ISSUE 2 Catholic Times September 17, 2017 Irma leaves path of destruction The Editor’s Notebook across Carribean and Florida Faith and Reason By David Garick, Editor Activity is returning to college campuses are addressed through as a new school year gets under way. It is a combination of faith a special time for our students. They are in the essential Living taking a very big step into an environment Word of God and hu- which will be very different from their life man reason rooted in at home with their parents. It’s a special the intellectual gifts place, which they will occupy only for a humanity was endowed with as steward of few years in preparation for the life that lays this world, we find true understanding. ahead for them in what we humorously call This issue of Catholic Times will bring you the “real world.” up to date on some of the new things going Entering this special world of college life on in area Catholic colleges this year. We introduces the young student to some in- also take an in-depth look at one very spe- triguing new realities. As a college student, cial Catholic college, the Pontifical College By Catholic News Service I learned that you only get clean clothes in Josephinum. A weakened Hurricane Irma churned into Florida after your closet if you take all your dirty clothes Nowhere is the quest for truth and rea- ripping through southern portions of the state and the Ca- to the laundromat and put lots of quarters son more evident and more critical than in ribbean islands, flooding cities, knocking out power to mil- into the machines. -

(R)Evolution in Consumption, Community, Urbanism, and Space

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: EASTON: A 21ST CENTURY (R)EVOLUTION IN CONSUMPTION, COMMUNITY, URBANISM, AND SPACE John Michael Ryan, Masters of Arts, 2005 Thesis directed by: Dr. George Ritzer, Distinguished University Professor Department of Sociology This research was designed, planned, and implemented with three overarching and interrelated objectives in mind – to apply existing theoretical knowledge on consumption, community, urbanism, and space to the specific case study of Easton Town Center; to enhance, contribute, and extend the research and literature surrounding these four areas; and to flesh out the paradigm of Easton into a more coherent, comprehensive theory with potential applications for future social scientific inquiry. EASTON: A 21ST CENTURY (R)EVOLUTION IN CONSUMPTION, COMMUNITY, URBANISM, AND SPACE By John Michael Ryan Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Distinguished University Professor George Ritzer, Chair Professor David Segal Associate Professor Joseph Lengermann ©Copyright by John Michael Ryan 2005 Table of Contents Chapter I: An Introduction to Easton 1 Why Columbus? 3 Relationship with Columbus 8 Easton as test market 11 Study Objectives 14 Chapter II: The Rise of Consumption Settings and Their Associated Mentality 18 Era of Social Trading 20 Early bartering 21 Greek Agora 21 Roman Forum 22 Markets and fairs 23 The Industrial Revolution 25 Era of Production -

2014 Annual Budget Report 0.Pdf

The Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to Columbus Metropolitan Library, Ohio for its annual budget for the fiscal year beginning January 1, 2013. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as an operations guide, as a financial plan, and as a communications device. The award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. TABLE OF CONTENTS COLUMBUS METROPOLITAN LIBRARY 96 S. Grant Avenue - Columbus, Ohio 43215 Tel: 614-645-2ASK (2275) - Fax: 614-849-1365 2014 ANNUAL BUDGET January 1, 2014 - December 31, 2014 Introductory Section Page Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ i Library Officials and Staff .............................................................................................. 1 Budget Message Budget Overview ................................................................................................ 4 Graphs: Where the Money Comes From and Where It Goes ............................ 5 Financial Highlights by Fund .............................................................................. 6 2014 Budget Strategy ........................................................................................ -

2020 Senior Calendar

® SimplySimply EZEZ ® Fresh, Healthy Meals Delivered Weekly For Over 20 Years Serving PASSPORT MyCare, Ohio Home Care, Levy Funded Programs, Private Pay in Districts 1, 2, 6, 7 www.SimplyEZ.net • 877-396-3251 1 2 The New Generation of Large Variety of Meals Home Delivered Meals Excellent Consumer Care Multiple Funding Sources Our goal is to deliver high-quality delicious meals right to our consumer’s door. We offer an amazing variety of options with our Standard and Kosher menus, plus incredible flavors with our specialty menus: Mexican Fiesta, Asian Table, All American, Global Bistro, Marie Callender’s, Signature Brunch and Soups. Our Gluten Free, Low Sodium, Vegetarian and Soft Diet menus meet dietary needs without sacrificing taste. FUNDING SOURCES • SERVING ALL OF OHIO Certified Statewide: PASSPORT, MyCare Ohio, Ohio Home Care Waiver Program, Ohio DODD Certified by County: Franklin County Office on Aging, Cuyahoga County Division of Senior & Adult Services, McGregor PACE - Cuyahoga County Contact us to get started: Toll Free: 1.888.928.2323 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.globalmeals.com Fax: 614.228.1746 2 3 Providing , affordable senior housing quality Michigan Avenue, Cambridge Arms, Horizon House, Columbus, OH Columbus, OH Portsmouth, OH Community Properties of Ohio is an affiliate of Ohio Capital Corporation Jenkins Terrace, Columbus, OH Worley Terrace, Columbus, OH for Housing. Our organizations fully support the principles of the Michigan Avenue: 614.545.3055 Jenkins Terrace: 614.421.6374 Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental, Cambridge Arms: 614.545.3055 Worley Terrace: 614.421.4442 and financing of dwellings, and in Horizon House: 740.354.6393 other housing-related transactions, based on race, color, national origin, religion, gender, familial status, Corporate Office: military status or disability.