Acrylamide Investigation: Phase 1 Analysis of All Group Samples Sponsors Project Reference No: FS102081 Distribution: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sugar: the Many Names Used in Processed Foods

Sugar: the Many Names Used in Processed Foods Both glucose and fructose are common, but they affect the body very differently. Glucose can be metabolized by nearly every cell in the body. Fructose is metabolized almost entirely in the liver. Fructose has harmful effects on the body, including insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, and type 2 diabetes. It is especially important to minimize the intake of high fructose sugars. Many processed foods will have a combination of sugars. Because the ingredient are listed in order of quantities, using several different sugar names presents the illusion that sugars are less prominent in the ratio of ingredients. Sugar / Sucrose Agave Nectar Sugar with Glucose & Fructose Also knows as table, granulated, or Produced from the agave plant in Various Amounts white sugar, occurring naturally in 79-90% fructose, 10-30% glucose Beet Sugar fruits and plants, added to many Blackstrap Molasses processed foods. Sugar with Fructose Only Brown Sugar, Dark or Light Brown 50% glucose, 50% fructose Crystalline Sugar Fructose Buttered Syrup High Fructose Corn Syrup, HFCS Cane Juice Crystals Sugar without Glucose or HFCS 55 – the most common type Fructose Cane Syrup of HRCS. 55% fructose, 45% D-Ribose, Ribose Cane Sugar glucose, composition is similar to Galactose Caramel sucrose Caramel Color HFCS90 – 90% fructose, 10% Names for Hidden Sugars Carob Syrup glucose Aguamiel Castor Sugar All-natural sweetener Coconut Sugar Names Used to Denote Hight Barbados Molasses Confectioner’s Sugar (Powdered Fructose -

Brown Sugars Brochure

Add flavour, colour and texture with our range of brown sugars Brown Sugars Our comprehensive range of golden, brown and Muscovado sugars are produced from homegrown beet and the finest quality cane Brown Sugars Applications • Use as a bakery ingredient to add flavour and colour to cakes, biscuits and pastries • Demerara sugar adds texture to toppings and bases • Ideal for use in the manufacture of confectionery products such as toffee, fudge and caramel • Used in dressings, sauces and marinades: adds a mild to full-bodied extra flavour The Brown Sugar range Production Benefits Product Properties Benefits (Product Code) Ideal for use in both large Soft Light Brown Based on caster sugar – a • A consistently bright, golden colour Sugar consistent particle size, scale, automated production 55658 – 25kg moist, free-flowing, light • Gives a fine crumb texture in processes and craft bakeries golden brown crystal, pre-production and excellent cake delicately flavoured with volume in the finished product • Easy to handle and dose molasses • Fine particle sizes ensure rapid dissolving for syrups, sauces, • Reproducible results caramels and toffees every time: Soft Dark Brown Based on caster sugar – a • Provides molasses and black - consistent particle size Sugar moist, free-flowing, treacle flavour without bitterness 55674 – 25kg consistent particle size, dark golden brown crystal • A dark rich uniform colour - uniform colour Demerara Sugar Dry, golden brown bold • A consistent bright golden colour - controlled moisture content 55688 – 25kg crystals * Enquire for availability Demerara Sugar: adds texture to toppings and bases Brown Cane Sugars Billington’s brown sugars are the finest collection of cane sugars in the world. -

Brick 10006390: Chewing Gum

Brick 10006390: Chewing Gum Definition Includes any products that can be described/observed as a type of gum made of chicle, a natural latex product, or synthetic equivalents such as polyisobutylene. Includes Bubble gum, which is a type of chewing gum, designed to be inflated out of the mouth as a bubble. Excludes Non–Chewing Gums and Anti–smoking treatments, and products that claim to be primarily Health Care or specific purpose gums such as Oral Care related like whiting, teeth cleansing. Diabetic Claim (20000056) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, whether the product makes a claim to be suitable for consumption by consumers who have diabetes. Attribute Values NO (30002960) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) YES (30002654) Special Occasion Claim (20000165) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify whether the product is intended to be consumed for a special occasion. Attribute Values NO (30002960) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) YES (30002654) Sugar Level Claim (20000174) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging, the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to describe the level of sugar that is contained within the product. Page 1 of 15 Attribute Values CONTAINS SUGAR LOW SUGAR (30001471) UNCLASSIFIED (30002515) (30000744) SUGAR FREE (30002356) UNIDENTIFIED (30002518) Type of Chewing Gum (20002894) Attribute Definition Indicates, with reference to the product branding, labelling or packaging the descriptive term that is used by the product manufacturer to identify a particular type or variety of chewing gum. -

Be-Ro Recipes, Unless Otherwise Stated

www.be-ro.co.uk Recipe Inspiration From the www.be-ro.co.uk website. www.be-ro.co.uk Be-Ro Recipe Book Since 1923 and now in its 41st Edition ! Containing over 125 recipes, and helpful hints and tips Order your copy on-line at www.be-ro.co.uk Baking Basics Here you'll find all the information you need to becoming a baking expert. From choosing your ingredients through to testing your finished cake, all the help you need is right here. - Basics Recipe Remedies If your sponge is too soggy or your pastry is too crumbly, we have - Remedies the solution right here. Our helpful advice will give you all the answers you need to solve those tricky baking problems. - Recipes Recipe Inspiration Here you'll find great ideas for all kinds of recipes, from quick and easy meals through to recipes for the baking expert. Welcome to Baking Basics These are core recipes and skills and other information that you’ll need for preparing many of the other recipes in this collection. But more than that… these basics will provide you with the fundamental - Basics knowledge that will serve you well for all your baking needs in future ! • A Word about our Recipes • Melting Method • A Word on Ingredients • Metric / Imperial Measurements - Remedies • Baking with Be-Ro • Other Useful Measures • Batch Baking • Oven Management • Cake Basics • Pastry Basics • Celebration Fruit Cakes • Pie Basics • Choux Pastry • Rolling Brandy Snaps - Recipes • Cooking in your Microwave • Rough Puff Pastry • Creaming Method • Rubbed in Method • Flaky Pastry • Shortcrust Pastry • Flan Basics • Steamed Puddings • Home Freezing • Suet Pastry • Lining a Pudding Basin • Whisking Method A Word about our Recipes… We have categorised our recipes in order to help you judge the level of expertise required for each one. -

Effect of Sugarcane Juice Pre-Treatment on the Quality and Crystallization of Sugarcane Syrup (Treacle)

cess Pro ing d & o o T F e c f h o n l o a l n o Journal of Food Processing & r g u y o J ISSN: 2157-7110 Technology Research Article Effect of Sugarcane Juice Pre-Treatment on the Quality and Crystallization of Sugarcane Syrup (Treacle) Waled M. Abdel-Aleem* Central Laboratory of Organic Agriculture, Agricultural Research Centre, Minia, Egypt ABSTRACT Treacle (black honey) is liquid syrup produced by heating and evaporation of sugarcane juice. It is rich in sugars including, sucrose, glucose, and fructose, which may crystallize during storage, especially at low temperatures. The crystallization of treacle was the main problem facing treacle producers in the Egyptian traditional food industry and affected negatively in the quality and consumer acceptability. Consequently, the aimed to investigate the effect of sugarcane juice pre-treatments, including the addition of citric acid at concentrations of (1, 2, and 3) g/l alone or in a combination with preheating at (60 or 70)°C for 1 h on physiochemical properties and crystallization of sugarcane syrup during storage for 60 days at room temperature. The results showed that these pre-treatments significantly affected the quality and properties of sugar cane syrup. The combination of the citric acid addition at a concentration of 1 g/l and preheat treatment at 70°C for 1 h resulted in syrup with the greatest overall acceptability. Also, these pre- treatments prevented the crystallization of the produced syrup during the storage for 60 days at room temperature (20 ± 5)°C. Therefore, pre-treatment of the sugar cane syrup with a combination of the citric acid addition and heating can be suggested as a promising method for producing a high-quality sugar can syrup and preventing syrup crystallization during storage and handling. -

A Key to the Field Identification of Sugar Cane Diseases, 571

Index A Key to the Field Identifi cation of Sugar Cane Clean Air Act (1963), 738 Diseases, 571 Clean Waters Act (1971), 735 Abbotsford Mill, 93 Crown Lands Alienation Act (1868), 44 Abergowrie, 292, 297 Discharged Soldiers’ Settlement Act (1917), 274 Abergowrie Scheme, 299, 300, 659 Diseases in Plants Act (1929), 575, 586 Aborigines: Imported Sugar Refi ners Act (1874), as canecutters, 630, 631, 633, 635, 637; as fi eld 232–233 labourers, 84, 88, 341; attacks on sugar Leasing Act (1866), 44 plantations, 1, 49; employed by Fairymead Local Government Act (1936), 408, 425 Sugar Co. Ltd., 630; gather seed from Plant Protection Act (1989), 602 legume crops on Palm Island, 354 Primary Producers’ Organisation and Marketing Acclimatisation Society, Queensland, 147, 148, Act (1926), 279 474; see also Q. 813 cane variety Queensland Harbours Act (1955), 794 A.C.F. and Shirleys Fertilisers Ltd., 357, 371, Regulation of Sugar Cane Prices Act (1915) 372, 373 (and subsequent amendments to), 272, acid sulphate soils, 440–441, 836 279, 281, 284, 289, 321, 575, 664, 689– Acts of Parliament: 690, 693, 695, 697 Australia: River Improvement Trust Act (1940), 409 Australian Industries Preservation Act (1906), Sugar Acquisition Act (1915), 770, 776 257 Sugar and Shearers’ Workers Accommodation Commercial Activities Act (1919), 773 Act (1905), 60, 614 Custom Tariff (Sugar Duties) Act (1922), 775 Sugar Cultivation Act (1913), 63, 108 Excise Tariff Act (1902), 58 Sugar Experiment Stations Act (1900) (and Excise Tariff Act (1905), 59 subsequent amendments to), 138, -

Mmm...Why Do We Love Sugar So Much?

I Sugar by Elizabeth Preston art by Amanda Shepherd Mmm....Why do we love sugar so much? rom chocolate Building Sweet the simple sugars can cookies to crisp, “Sugar” is the name for be found in plants. Fjuicy apples, we many different sweet- Fructose is what makes humans are sweet on tasting molecules. fruits taste sweet, for sugar. And that’s only They’re all made of example. natural. All plants and carbon, hydrogen, and Combining these I need fuel. animals need sugar to oxygen atoms. simple sugars makes live. It’s the fuel that There are three other kinds of sugar. powers our cells. So it’s basic sugar building The most common is not surprising we’re blocks, or “simple sucrose, also called hard-wired to crave the sugars.” These are table sugar. The sugar sweet stuff. called fructose, glucose, your family keeps in and galactose. All of the kitchen for baking, fructose glucose Three simple sugars— galactose fructose, glucose, and galactose—snap together in different ways to form many other kinds of sugar, a little like Legos. H ? ow ar M uc h Sug sucrose lactose art © 2016 by Amanda Shepherd © 2016 by Elizabeth Preston, text 12 a s k I Sugar or in the sugar bowl? in their milk as babies. That’s sucrose. Brown But some people grow sugar, powdered sugar, up to be “lactose intol- and molasses are erant,” which means sucrose too. Most of the their bodies can’t digest sucrose we eat comes this sugar anymore. 3 teaspoons from sugar beets and High-fructose corn natural sugar H sugarcane. -

Paul's Treacle Tart

Treacle Tart Paul Clerehugh recipes as featured on the Nicki Whiteman Show Paul Clerehugh is BBC Radio Berkshire’s guest chef. He is chef proprietor of the Crooked Billet, one of England’s most famous foodie pubs. Some cooks and restaurants get awfully fancy with treacle tarts – pecan nuts in it, pointless pastry lattice on top. All you need is fresh breadcrumbs made from slightly stale bread, more golden syrup than you thought possible and a generous squeeze of lemon juice, a tang of acidity from the lemon provides the perfect counterbalance to all this sweetness. It is wonderful served warm with clotted cream but for those with a very sweet tooth – custard sauce has got to be the ultimate sleeping partner. Paul Clerehugh Serves 6 200g plain flour A pinch of salt 50g cold butter, cut into pieces 50g lard, cut into pieces 2-3 tbsp cold water 175g white breadcrumbs 7-8 tbsp golden syrup juice of ½ a lemon Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/Gas 6. Stand the tin of golden syrup in a pan of boiling water (this just makes it easier to pour). 1. Sift the flour into a large mixing bowl with the salt. Add the butter and lard and quickly rub it into the flour until the mixture resembles heavy breadcrumbs. 2. Add the water, a little at a time and use a knife to stir it up into a clump. Knead it a couple of times, pat into a ball, cover and set aside for 30 minutes. bbc.co.uk/berkshire 3. -

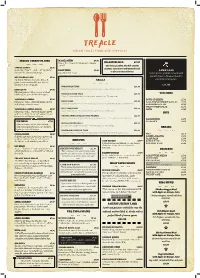

76046 TREACLE MENU a .Pdf

INDIAN STREET PLATES MASALA CHIPS £4.90 Crispy thin fries with Indian style masala KOLHAPURI ALOO £7.90 garnish. Our Chefs speciality, this dish contains PAPPAD KICHDI £5.90 peanuts, curry leaves and mustard seeds Colourful crispy rice and flour papadums PLAIN FRIES £3.90 to give you a nutty flavour. LAMB SAAG served with assorted chutneys. Just plain thin fries! Select pieces of lamb stewed with spinach leaves. Flavoured with a MIX PAKORA PLATE £5.90 Authentic Indian street style broccoli, GRILLS warm blend of spices. potato, onion and cauliflower fritters, served with a chilli sauce. £11.90 MURGH MALAI TIKKA £10.90 CHICKEN 69 £6.90 Yoghurt and spices marinated boneless chicken pieces cooked in our Indian oven. Chicken pakora with a twist of crushed VEG SIDES black pepper served with chilli sauce. TREACLE CHICKEN TIKKA £10.90 Chargrill flavoured boneless chicken pieces cooked in our Tandoor oven. VEGETABLE SAMOSA £5.90 BOWL OF GREENS £5.90 Filo pastry with a vegetable filling served SEEKH KEBAB £11.90 KALA CHANA (CHICKPEA) SALAD £5.90 with a tangy chutney sauce. Seasoned mixed minced chicken and lamb put on skewers and cooked in our Tandoor oven. KACHUMBER SALAD £5.90 INDIAN GREEN SALAD £5.90 VEGETABLE SAMOSA CHAAT £6.90 SPICY LAMB CHOPS £11.90 RAITA £3.90 Lamb chops marinated in spices and then grilled in our Indian open. Filo pastry with a vegetable filling topped RICE with curried chickpeas and yoghurt sauce, mint sauce and tamarind sauce. SARSOKA JHINGA (GRILLED TIGER PRAWNS) £11.90 Tiger prawns marinated in a delicate blend of Indian spices then grilled in our Indian oven. -

Tate & Lyle Black Treacle

Tate & Lyle Black Treacle (454g) Additional Information Product Code 406396 LYLES BLACK TREACLE 12X454G CAN - A thick black invert formed of a combination of sucrose, glucose and fructose found naturally in sugar Product Description cane. Also commonly described as a ‘molasses’. It has a powerful and slightly bitter flavour. Height (mm) 88.0000 Length (mm) 244.0000 Width (mm) 334.0000 Outer EAN 1 5010115902064 Storage Type Ambient Brand Tate and Lyle Ingredients Ingredients Cane Molasses. Contains Naturally Occuring Sulphites. Dietary Information Approved for a Halal Diet Yes Approved for a Kosher Diet Yes Suitable for Coeliacs Yes Suitable for Lactose-Free Diet Yes Suitable for a Vegan Diet Yes Suitable for a Vegetarian Diet Yes 26/09/2021 1 https://www.henderson-foodservice.com/tate-lyle-black-treacle-12-x-454gm.html Allergens Celery No Gluten No Crustacea No Eggs No Fish No Lupin No Milk No Molluscs No Mustard No Nuts No Peanuts No Sesame No SOYA No Sulphites >10mg Nutritional Information Carbohydrate Per 100g (g) 64 g Carbohydrate of which Sugars per 100g (g) 64 g Energy per 100g (kcal) 290 kcal Energy per 100g (kJ) 1230 kJ Protein per 100g (g) 1.7 g Salt per 100g (g) 0.13 g Disclaimer: While we endeavour to ensure the accuracy of all product, pricing and nutritional data at all times, and that information is provided in good faith, we are not the manufacturers of these products and any such information we provide is therefore reliant on the accuracy and completeness of information provided to us by our suppliers. -

Your Complete Usage Guide for CSR Sugars and Syrups

Your complete usage guide for CSR Sugars and Syrups CSR YOUR SUGAR EXPERTS For more than 160 years, CSR Sugar has been producing sugar of all varieties for Australians to cook with. Established in 1855 out of the need for a local source of sugar, today CSR Sugar still produces sugar at multiple sites around Australia. Sugar is a truly multi-tasking and flexible food service ingredient. It’s an important addition in so many pre-prepared foods. It not only makes food taste good, but it has unique properties that aid in food production. These include: • A bulking agent – contributing • A flavour enhancer – enhancing to the bulk or body of products the taste of sour fruits. in baked goods such as meringues. • A unique colour and flavour – • In fermentation – providing food on heating, sugar caramelises for yeast in breads and buns in to produce a desirable colour order to produce carbon dioxide and flavour (browning). to raise the dough. • Lowering freezing point – helps • A preservative – helping to produce fine crystal structure reduce the growth of bacteria, and product smoothness in ice- moulds and yeast to extend shelf cream and other frozen desserts. life such as in jams. • Raising boiling point – enables • An aid to body and viscosity a more concentrated sugar – in liquid and semi-liquid solution which is important products such as syrups and in candy manufacture. sweet sauces. A RANGE OF SUGARS AND SYRUPS TO SUIT YOUR NEEDS CSR PRODUCT DESCRIPTION IDEAL FOR CSR White Sugar Its subtle sweetness lets Cakes, sweetening fruit other flavours shine through. -

Stages of Sugar Cookery Quadrant

Code and Title of the Paper: F01FS Food Science Code and Title of the Module: F01FS37 Stages of Sugars Name of the Content Writer: Dr. Munira Husain Stages of Sugar Cookery Quadrant - I Making Sugar Syrups and caramel always begins with heating and melting ordinary granulated sugar and recrystallizing it according to need. During the heating process the sugar first dissolves into syrup. As the temperature gets higher the syrup begins to thicken. As the temperature continues to rise and the water evaporates, the sugar begins to caramelize and turn a darker color. As long as there is a lot of water in the syrup mixture the temperature will not raise much above the boiling point. As the water begins to evaporate the temperature of the mixture also begins to rise. As the water continues to evaporate, the temperature continues to rise. When most of the water has evaporated the temperature of the syrup will begin to rise rapidly. At 320oF there is no water left, the sugar is melted and begins to caramelize, and the sweetness starts to decrease. The hotter the caramel gets the darker it becomes, and the deeper and less sweet the flavor becomes. Basically, temperature and the chemical interaction between a given component and the water molecule determine the component’s solubility in water. Sucrose can be kept in solution in pure water at temperatures between 0 and 140°C. At temperatures above 100°C, pressurisation is necessary to achieve the solubility. The relatively high solubility of sucrose is an important parameter for its bulking Code and Title of the Paper: F01FS Food Science Code and Title of the Module: F01FS37 Stages of Sugars Name of the Content Writer: Dr.