Sugar Refining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adsorption of Cd (II) and Pb (II) Using Physically Pretreated Camel Bone Biochar

Advanced Journal of Chemistry-Section A, 2019, 2(4), 347-364 http://ajchem-a.com Research Article Adsorption of Cd (II) and Pb (II) Using Physically Pretreated Camel Bone Biochar Mohamed Nageeb Rashed* , Allia Abd-Elmenaim Gad, Nada Magdy Fathy Faculty of Science, Aswan University, 81528 Aswan, Egypt A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Received: 15 April 2019 In this study, low-cost biochar adsorbent originated from camel Revised: 06 May 2019 bone was prepared by physical treatment, and the prepared camel Accepted: 05 June bone biochar for the removal of Cd2+ and Pb2+ from aqueous Available online: 10 June solutions was examined. The characterization of the prepared biochar adsorbent before and after the treatment with the metal DOI: 10.33945/SAMI/AJCA.2019.4.8 solutions was done by using XRD, SEM, FT-IR, and BET surface isotherm. The bone sample was pyrolyzed at temperature 500, 600, 800, and 900 °C. Adsorption efficiency of Pb and Cd were optimized K E Y W O R D S by varying different parameters viz., pH, pHz, contact time, initial Wastewater metal concentration, adsorbent dosage, and temperature. Nature of Lead the adsorption process is predicted by using adsorption kinetic, Cadmium isotherms, and thermodynamic models. The results revealed that the Camel Bone effective pyrolysis of camel bone achieved at 800 °C which possess Biochar high removal capacity. The maximum adsorption removal percentage for Cd and Pb were 99.4 and 99.89%, respectively at contact time of 1 h, adsorbent dosage of 1 g, pH=5, and initial metal concentration 10 mg/L of both metal salts. -

Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Ashes for Greener Concrete Master’S Project for the Master Program of Structural

Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Master’s Thesis ACEX30-19-97 Gothenburg, Sweden 2019 MASTER’S THESIS ACEX30-19-97 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Göteborg, Sweden 2019 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ © ARNAUD GLIKSON, SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ, 2019 Examensarbete ACEX30-19-97 Institutionen för arkitektur och samhällsbyggnadsteknik Chalmers tekniska högskola, 2019 Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Göteborg Sweden Telephone: + 46 (0)31-772 1000 Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Göteborg, Sweden, 2019 Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes for greener concrete Master’s project for the Master Program of Structural Engineering and Building Technology ARNAUD GLIKSON SARA LÓPEZ MENÉNDEZ Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering Division of Building Technology Building Materials Chalmers University of Technology ABSTRACT Owing to the varying characteristics of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) ashes and the lack of harmonized standards and regulations, a substantial portion of MSWI ashes are simply used as landfilling cover at the present, which can be better utilized in the viewpoint of sustainability. -

Activated Carbon, Biochar and Charcoal: Linkages and Synergies Across Pyrogenic Carbon’S Abcs

water Review Activated Carbon, Biochar and Charcoal: Linkages and Synergies across Pyrogenic Carbon’s ABCs Nikolas Hagemann 1,* ID , Kurt Spokas 2 ID , Hans-Peter Schmidt 3 ID , Ralf Kägi 4, Marc Anton Böhler 5 and Thomas D. Bucheli 1 1 Agroscope, Environmental Analytics, Reckenholzstrasse 191, CH-8046 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Soil and Water Management Unit, St. Paul, MN 55108, USA; [email protected] 3 Ithaka Institute, Ancienne Eglise 9, CH-1974 Arbaz, Switzerland; [email protected] 4 Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Department Process Engineering, Überlandstrasse 133, CH-8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland; [email protected] 5 Eawag, Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, Application and Development, Department Process Engineering, Überlandstrasse 133, CH-8600 Dübendorf, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-58-462-1074 Received: 11 January 2018; Accepted: 1 February 2018; Published: 9 February 2018 Abstract: Biochar and activated carbon, both carbonaceous pyrogenic materials, are important products for environmental technology and intensively studied for a multitude of purposes. A strict distinction between these materials is not always possible, and also a generally accepted terminology is lacking. However, research on both materials is increasingly overlapping: sorption and remediation are the domain of activated carbon, which nowadays is also addressed by studies on biochar. Thus, awareness of both fields of research and knowledge about the distinction of biochar and activated carbon is necessary for designing novel research on pyrogenic carbonaceous materials. Here, we describe the dividing ranges and common grounds of biochar, activated carbon and other pyrogenic carbonaceous materials such as charcoal based on their history, definition and production technologies. -

Concept Papers for Changes to Rule 9-1 -- Refinery Fuel Gas Sulfur

Draft: 05‐14‐15 Appendix C: Concept Paper for Changes to Rule 9‐1: Refinery Fuel Gas Sulfur Limits Rules to Be Amended or Drafted Regulation of refinery fuel gas (RFG) requires amendments to Air District Regulation 9, Rule 1, Sulfur Dioxide. Goals The goal of this rulemaking is to achieve technically feasible and cost‐effective sulfur dioxide (SO2) emission reductions from RFG systems at Bay Area refineries. Background The lightest components of crude oil separated by a refinery’s atmospheric fractionator are methane and ethane, which are also the primary components of natural gas. At petroleum refineries, these products are not produced in marketable quantities, but are used as fuel in the numerous onsite steam generators and process heaters. When produced at a refinery, this product is called refinery fuel gas (RFG). Pipeline natural gas may be used as a supplemental fuel when needed to enhance the quality of RFG or when there is not enough RFG available. Unlike, pipeline natural gas, refinery fuel gas often contains significant quantities of sulfur that occur naturally in crude oil. When burned, these sulfur compounds are converted to SO2. Process and Source Description RFG can contain between a few hundred and a few thousand parts per million‐volume (ppmv) sulfur in the form of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), carbonyl sulfide (COS), and organic sulfur compounds, such as mercaptans. During combustion, the sulfur in all of these compounds will oxidize to form SO2, which is a criteria air pollutant and a precursor to particulate matter. Scrubbing with an amine or caustic solution can be effective at removing H2S and some acidic sulfur containing compounds, but is generally ineffective at removing nonacidic sulfur compounds. -

Opportunities for Geologic Carbon Sequestration in Washington State

Opportunities for Geologic Carbon Sequestration in Washington State Contributors: Jacob R. Childers, Ryan W. Daniels, Leo F. MacLeod, Jonathan D. Rowe, and Chrisopher R. Walker Faculty Advisor: Juliet G. Crider Department of Earth and Space Sciences University of Washington, Seattle May 2020 ESS Special Topics Task Force Report 001 Preface and Acknowledgment This report is the product of reading, conversation, writing and revision by a group of undergraduate student authors during 10 weeks of March, April and May 2020. Our intent is to review the basic processes and state of current scientific understanding of geologic carbon sequestration relevant to Washington State. We would like to thank Dr. Thomas L. Doe (Golder Associates) for reading the final report and asking us challenging questions. i I. Introduction Anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gasses like CO2 are raising global temperatures at an unprecedented rate. According to the most recent United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, global emissions have caused ~1°C global warming above pre-industrial levels, with impacts such as rising sea level and changing weather patterns (IPCC 2018). The IPCC states that the current rate of emissions will lead to global warming of 1.5°C sometime between 2030 to 2052, and that temperature will continue to rise above that if emissions are not halted. They state that impacts of global warming, such as drought or extreme precipitation, will increase with a 1.5°C temperature increase. However, these effects will be less than the impacts of global temperature increase of beyond 2°C. The IPCC also projects that global sea level rise will be 0.1 m lower at 1.5°C warming than at 2°C warming, exposing 10 million fewer people to risks related to sea level rise. -

Sugar: the Many Names Used in Processed Foods

Sugar: the Many Names Used in Processed Foods Both glucose and fructose are common, but they affect the body very differently. Glucose can be metabolized by nearly every cell in the body. Fructose is metabolized almost entirely in the liver. Fructose has harmful effects on the body, including insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver, and type 2 diabetes. It is especially important to minimize the intake of high fructose sugars. Many processed foods will have a combination of sugars. Because the ingredient are listed in order of quantities, using several different sugar names presents the illusion that sugars are less prominent in the ratio of ingredients. Sugar / Sucrose Agave Nectar Sugar with Glucose & Fructose Also knows as table, granulated, or Produced from the agave plant in Various Amounts white sugar, occurring naturally in 79-90% fructose, 10-30% glucose Beet Sugar fruits and plants, added to many Blackstrap Molasses processed foods. Sugar with Fructose Only Brown Sugar, Dark or Light Brown 50% glucose, 50% fructose Crystalline Sugar Fructose Buttered Syrup High Fructose Corn Syrup, HFCS Cane Juice Crystals Sugar without Glucose or HFCS 55 – the most common type Fructose Cane Syrup of HRCS. 55% fructose, 45% D-Ribose, Ribose Cane Sugar glucose, composition is similar to Galactose Caramel sucrose Caramel Color HFCS90 – 90% fructose, 10% Names for Hidden Sugars Carob Syrup glucose Aguamiel Castor Sugar All-natural sweetener Coconut Sugar Names Used to Denote Hight Barbados Molasses Confectioner’s Sugar (Powdered Fructose -

Papers of Beatrice Mary Blackwood (1889–1975) Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford

PAPERS OF BEATRICE MARY BLACKWOOD (1889–1975) PITT RIVERS MUSEUM, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Compiled by B. Asbury and M. Peckett, 2013-15 Box 1 Correspondence A-D Envelope A (Box 1) 1. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 May 1955. Summary: Acknowledging receipt of the Pitt Rivers Report for 1954. “The Museum as an institution seems beset with more difficulties than any other.” Giving details of the developing organisation of the Vancouver Museum and its index card system. Asking for a copy of Mr Bradford’s BBC talk on the “Lost Continent of Atlantis”. Notification that Mr Menzies’ health has meant he cannot return to work at the Museum. 2pp. 2. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 20 July 1955. Summary: Thanks for the “Lost Continent of Atlantis” information. The two Museums have similar indexing problems. Excavations have been resumed at the Great Fraser Midden at Marpole under Dr Borden, who has dated the site to 50 AD using Carbon-14 samples. 2pp. 3. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 12 June 1957. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Mr Menzies and his health. The Vancouver Museum is expanding into enlarged premises. “Until now, the City Museum has truly been a cultural orphan.” 1pp. 4. Letter from TH Ainsworth of the City Museum, Vancouver, Canada, to Beatrice Blackwood, 16 June 1959. Summary: Acknowledging the Pitt Rivers Museum Annual Report. News of Vancouver Museum developments. -

Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG)

Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Demand, Supply and Future Perspectives for Sudan Synthesis report of a workshop held in Khartoum, 12-13 December 2010 The workshop was funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development Cover image: © UNAMID / Albert Gonzalez Farran This report is available online at: www.unep.org/sudan Disclaimer The material in this report does not necessarily represent the views of any of the organisations involved in the preparation and hosting of the workshop. It must be noted that some time has passed between the workshop and the dissemination of this report, during which some important changes have taken place, not least of which is the independence of South Sudan, a fact which greatly affects the national energy context. Critically, following the independence, the rate of deforestation in the Republic of Sudan has risen from 0.7% per year to 2.2% per year, making many of the discussions within this document all the more relevant. Whilst not directly affecting the production of LPG, which is largely derived from oil supplies north of the border with South Sudan, the wider context of the economics of the energy sector, and the economy as a whole, have changed. These changes are not reflected in this document. This being said, it is strongly asserted that this document still represents a useful contribution to the energy sector, particularly given its contribution to charting the breadth of perspectives on LPG in the Republic of Sudan. Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG) Demand, Supply and Future Perspectives for Sudan Synthesis report of a workshop held in Khartoum, 12-13 December 2010 A joint publication by: Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Physical Development – Sudan, Ministry of Petroleum – Sudan, United Kingdom Department for International Development, United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Table of contents Acronyms and abbreviations . -

BOOK of ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 13/Dja/P-23

BOOK OF ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 13/Dja/P-23 3rd International Workshop Mechanisms and modelling of waste/cement interactions Ghent, 06-08 May 2013 SCK•CEN Boeretang 200 BE-2400 MOL Belgium http://www.sckcen.be BOOK OF ABSTRACTS SCK•CEN-BA-53 3rd International Workshop Mechanisms and modelling of waste/cement interactions Ghent, 06-08 May 2013 SCK•CEN, Boeretang 200, BE-2400 MOL, Belgium Contact: Diederik Jacques Tel: +32 14 33 32 09 E-mail: [email protected] Organising committee Workshop convenors Geert De Schutter, UGent, B Diederik Jacques, SCK•CEN, B Hans Meeussen, NRG, NL Hans van der Sloot, ECN, NL Tom van Gerven, KU Leuven, B Lian Wang, SCK•CEN, B International Steering Committee Urs Berner, PSI, CH Céline Cau Dit Coumes, CEA, F Frederic Glasser, Aberdeen University, UK Bernd Grambow, SUBATECH, F James Kirkpatrick, Michigan State University, USA Barbara Lothenbach, Empa, CH André Nonat, Univ. Bourgogne, F © SCK•CEN Studiecentrum voor Kernenergie Centre d’Etude de l’Energie Nucléaire Boeretang 200 BE-2400 MOL Belgium http://www.sckcen.be Status: Unclassified RESTRICTED All property rights and copyright are reserved. Any communication or reproduction of this document, and any communication or use of its content without explicit authorization is prohibited. Any infringement to this rule is illegal and entitles to claim damages from the infringer, without prejudice to any other right in case of granting a patent or registration in the field of intellectual property. Copyright of the individual abstracts and papers rests with the authors and the SCK•CEN takes no responsability on behalf of their content and their further use. -

CCS: Applications and Opportunities for the Oil and Gas Industry

Brief CCS: Applications and Opportunities for the Oil and Gas Industry Guloren Turan, General Manager, Advocacy and Communications May 2020 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Applications of CCS in the oil and gas industry ............................................................................. 2 3. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Page | 1 1. Introduction Production and consumption of oil and gas currently account for over half of global greenhouse gas emissions associated with energy use1 and so it is imperative that the oil and gas industry reduces its emissions to meet the net-zero ambition. At the same time, the industry has also been the source and catalyst of the leading innovations in clean energy, which includes carbon capture and storage (CCS). Indeed, as oil and gas companies are evolving their business models in the context of the energy transition, CCS has started to feature more prominently in their strategies and investments. CCS is versatile technology that can support the oil and gas industry’s low-carbon transition in several ways. Firstly, CCS is a key enabler of emission reductions in the industries’ operations, whether for compliance reasons, to meet self-imposed performance targets or to benefit from CO2 markets. Secondly, spurred by investor and ESG community sentiment, the industry is looking to reduce the carbon footprint of its products when used in industry, since about 90% of emissions associated with oil and gas come from the ultimate combustion of hydrocarbons – their scope 3 emissions. Finally, CCS can be a driver of new business lines, such as clean power generation and clean hydrogen production. From the perspective of the Paris Agreement, however, the deployment of CCS globally remains off track. -

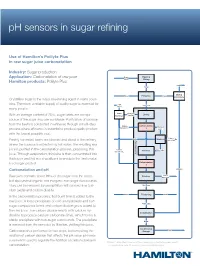

Ph Sensors in Sugar Refining

pH sensors in sugar refining Use of Hamilton’s Polilyte Plus in raw sugar juice carbonatation Industry: Sugar production Application: Carbonatation of raw juice Sugar Washing Beets Slicing Hamilton products: Polilyte Plus Pellets Slices Drying Water Extraction Scraps Pelletation Crystalline sugar is the major sweetening agent in many coun- Lime tries. Therefore, a reliable supply of quality sugar is essential for Raw Juice CaCO3 many people. Lime Lime milk Ca(OH) Liming With an average content of 20%, sugar beets are a major burning 2 source of the sugar sucrose worldwide. Purification of sucrose from the beets is conducted in refineries through a multi-step Carbon Carbonatation Washing dioxide CO process where efficiency is essential to produce quality product 2 1 water with the lowest possible cost. Lime + Water Washing Freshly harvested beets are cleaned and sliced at the refinery, impurities g where the sucrose is extracted by hot water. The resulting raw Cleanin juice is purified in the carbonatation process, producing thin Carbon Filtration Filter cake dioxide CO2 juice. Through evaporation, thin juice is then concentrated into Juice thick juice and fed into crystallizers to produce the final crystal- Carbonatation lized sugar product. 2 Carbonatation and pH Melasse Lime + Raw juice contains about 99% of the sugar from the beets, Filtration impurities but also several organic and inorganic non-sugar compounds. They can be removed by precipitation with burned lime (cal- Thin Juice cium oxide) and carbon dioxide. Steam Thickening Steam In the carbonatation process, first burnt lime is added to the raw juice. A loose precipitate of calcium hydroxide and non- Thick Juice sugar compounds forms and carbon dioxide gas is added to the raw juice. -

Effect of Agronomic and Storage Practices on Raffinose, Reducing Sugar, and Amino Acid Content of Sugarbeet Varieties1

Effect of Agronomic and Storage Practices on Raffinose, Reducing Sugar, and Amino Acid Content of Sugarbeet Varieties1 R. E. WYSE AND S. T. DEXTER2 Received fo,- /Jub lication July IO. 1970 Introduction The decrease in bagged sucrose per ton of beets during stor age results primarily from two factors. Sucrose is respired, evolv ing CO2 , The transformation of sucrose and other beet con stituents into raffinose, reducing sugars, amino acids, etc., re sults in an accumulation of non-sucrose solutes in the thin juice and corresponding increased sucrose losses into the molasses. Reducing sugars, raffinose and amino acids account for a major portion of the fluctuation in impurities during storage (Wyse et al.) 1970). The purpose of this study was to determine the in fluence of harvest date, nitrogen fertilization and storage tem perature on the content of these three impurities in several sugarbeet varieties. Reducing Sugars The predominant reducing sugars in the beet are glucose and fructose. Free galactose and arabinose are found only in trace amounts (Silin, 1964). Reducing sugars are presumably destroy ed during lime defecation and occur in very small amounts in beet molasses (McGinnis, 1951; Silin, 1964). In this process the reducing sugars are degTaded to acids (lactic, formic, acetic, sac charinic) (Carruthers et al.) 1959) which must be neutralized by the addition of sodium carbonate before evaporation to re duce soluble lime salts and to prevent sucrose inversiop (Silin, 1964; McGinnis, 1951). As a result of the addition of sodium carbonate, molasses quantity and purity are increased resulting in increased sucrose losses (Si Jin, 1%4).