Fusionist E-Mag Dec Issue Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Under Graduate Syllabus, Objectives and Outcomes (Cbcs)

DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN (CERAMIC & GLASS) KALA BHAVANA, VISVA-BHARATI UNDER GRADUATE SYLLABUS, OBJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES (CBCS) The four years Undergraduate BFA programme at Kala Bhavana begins with a 1-year Foundation Course. In the foundation course, the students get introduced with all discipline of visual art. Foundation course is followed by three years of specialization in Department of Design (Ceramic & Glass) I. Department of Design (Ceramic & Glass) component in the 1 year BFA Foundation programme Programme & Course Name Course Content Objective Expected Outcome Semester and Credits 1st. Year BFA – BFA/CG-F 1 It enhances /helps students to understand their In outdoor studies, students use very many Foundation 2 credits 1. Nature study on paper and immediate surroundings in the context of different traditional mediums and methods (Integrated basic understanding of observations of certain images and experiences which also help them to execute or approach Course) Ceramics ‘pottery/images they are gaining, more closely. They learn to images in multiple manners. articulate the use of lines, colours, shapes and Finally and most importantly they observe ST in coiling technique 1 . Semester forms of different given images around them. Also certain images around them and try to execute Course Name: (earthen ware). grows an understanding of different things from in different mediums, get attached to their BFA/CG-F 1, 2 Study of traditional daily observations, which gradually used in present situations and understand their own Course Credit: 2 terracotta forms and compositions. presence. Duration 90 Days copying in clay (earthen Learns multiple shapes, quality of objects, To develop their observation power/quality, (July to ware). -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli Islands 046908 Icelandic Col Social Pedagogy 001042 Kennarahaskoli Islands 002521 Taekniskoli Islands 002521 Technical College Iceland 001042 Univ Col Education Iceland 001041 Univ Iceland INDIA 000702 A Loyola Col 000678 Abhyuday Skt Col 000705 Ac Col 000705 Ac Col Commerce 000705 Ac Training Col 000629 Academy Of Architecture 000651 Acharatlal Girdharlal Teachers 000705 Acharya Brajendra Nath Seal Co 000701 Acharya Thulasi Na Col Commerc 000715 Adarsh Degree Col 000707 Adarsh Hindi Col 000715 Adarsh Vidya Mandir Shikshak 000710 Adarsha Col Ed 000698 Adarsha Ed Societys Arts Sci C 000710 Adhyapak Col 000701 Adichunchanagiri Col Ed 000701 Adichunchanagiri Inst Tech 000678 Adinath Madhusudan Parashamani 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Bhil 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Sant 000732 Adoni Arts Sci Col 000710 Ae Societys Col Ed 000715 Agarwal Col 000715 Agarwal Evening Col 000603 Agra University 000647 Agrasen Balika Col 000647 Agrasen Mahila Col 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Coimbat 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Killiku 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Madurai 000710 Agro Industries Foundation 000651 Ahmedabad Arts Commerce Col 000651 Ahmedabad Sci Col 000651 Ahmedabad Textile Industries R 000710 Ahmednagar Col 000706 Aizwal Col 000726 Aja Col 000698 Ajantha Ed Societys Arts Comme 000726 Ajra Col 000724 Ak Doshi Mahila Arts Commerce 000712 Akal Degree Col International Schools 000712 Akal Degree Col Women 000678 Akhil Bhartiya Hindi Skt Vidya 000611 Alagappa College Tech, Guindy 002385 -

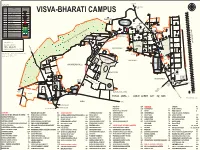

Updated Campus Map in PDF Format

KOPAI RIVER N NE LEGEND : NW E PRANTIK STATION W 1.5 KM SL. NO. NAME SYMBOL SE WS 1. HERITAGE BUILDING S 2. ADMIN. BUILDING VISVA-BHARATI CAMPUS 3. ACADEMIC BUILDING 42 4. GUEST HOUSE G 5. AUDITORIUM / HALL 101 6. HOSTEL BUILDING DEER PARK 44 7. CANTEEN C G RATAN PALLI 8. HOSPITAL LAL BANDH 01 41 SHYAMBATI 43 40 9. WATER BODY G 39 KALOR DOKAN 10. SWIMMING POOL 45 11. PLAY GROUND 38 93 91 90 UTTARAYANA/ 48 12. AGRICULTURE FARM RABINDRA BHAVANA 34 OLD MELA GROUND 94 POND (JAGADISH KANAN) 37 35 02 13. VILLAGE 33 47 T 98 92 46 G C T A T 14. WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 96 89 52 53 54 36 PM HOSPI AL 97 SIKSHA BHAVANA COMPLEX 50 51 04 E S A U R Y 100 03 15. ROAD 58 55 G SEVA PALLI 32 99 95 31 G 16. V.B.PROPERTY LINE D L F N PRATI ICH SRIPALLI SANGIT 60 KALA BHAVANA 57 LIPIKA I L I BHAVANA 56 30 N R LW E KALIGUNJE PEARSON PALLI 49 59 AMRAKUNJA 141 66 61 64 63 C 29 65 27 28 76 77 62 PATHA BHAVANA AREA NT LCERA L A 74 AY 68 75 LI RBR 103 67 EASTER AILIN AY PREPARED BY:- B A L V P U R W 25 78 102 F E PURVA PALLI C CENTRAL O FIC POUS MELA GROUND ESTATE OFFICE, SU 3 79 ASRAMA 80 26 73 81 RI 0 KM PLAY GROUND 24 VISVA - BHARATI 69 23 05 SIMANTAPALLI 83 22 SANTINIKETAN, PIN-731235 72 88 82 PLAY HATIPUKUR GROUND 85 84 SBI AUROSRI MARKET 21 86 71 LEGAL DISCLAIMER : THIS IS AN INDICATIVE MAP ONLY, 20 HATIPUKUR 70 16 FOR THE AID OF GENERAL PUBLIC. -

In Satyajit Ray's Documentary Films

i i i i DOI: 10.20287/doc.d21.ar5 Reading the ‘Facts’ in Satyajit Ray’s documentary films: a critical overview Shyamasri Maji* Resumo: Este artigo é sobre os filmes documentários de Satyajit Ray (1921-1992). Os seus documentários apresentam uma tapeçaria rica em criatividade, uma cinema- tografia requintada, uma música expressiva e, acima de tudo, uma maneira extraordi- nária de contar histórias. Em todos eles, Ray escreve o roteiro, compõe a música e realiza. Neste artigo, tentei analisar o seu estilo de representar os factos em filmes de não-ficção. Palavras-chave: biografias, filosofia tagoreana, narração, "verdade mais profunda". Resumen: Este artículo trata sobre las películas documentales de Satyajit Ray (1921- 1992). Los documentales de Ray presentan un rico tapiz de guión pensativo, cinema- tografía exquisita, música expresiva y sobre todo una forma extraordinaria de contar historias. En todos ellos, Ray ha escrito el guión, compuesto la música y dado la di- rección. En este trabajo, he tratado de analizar su estilo de representar los hechos en películas de no ficción. Palabras clave: biografías; filosofía tagoreana; voz en off ; "verdad más profunda". Abstract: This paper is about the documentary films of Satyajit Ray (1921-1992). Ray’s documentaries present a rich tapestry of thoughtful script, exquisite cinemato- graphy, expressive music and above all an extraordinary way of story-telling. In all of them, Ray has written the script, composed the music and given the direction. In this article, I have tried to analyse his style of representing the facts in non-fiction films. Keywords: biographies; tagorean philosophy; voiceover; “deeper truth.” Résumé: Cet article traite des films documentaires de Satyajit Ray (1921-1992). -

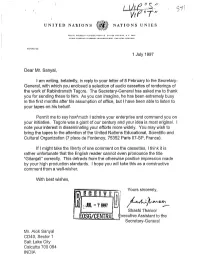

M R // Vvt/ Ffi*R~F~'R 7 F UNITED Natiions ||W NATIONS UNIES

M r // VVt/ ffi*R~f~'r 7 f UNITED NATiIONS ||W NATIONS UNIES s. N.V. loot? REFERENCE: 1 July 1997 Dear Mr. Sanyal, I am writing, belatedly, in reply to your letter of 8 February to the Secretary- General, with which you enclosed a selection of audio cassettes of renderings of the work of Rabindranath Tagore. The Secretary-General has asked me to thank you for sending these to him. As you can imagine, he has been extremely busy in the first months after his assumption of office, but I have been able to listen to your tapes on his behalf. Permit me to say how'much I admire your enterprise and commend you on your initiative. Tagore was a giant of our century and your idea is most original. I note your interest in disseminating your efforts more widely. You may wish to bring the tapes to the attention of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07-SP, France). If I might take the liberty of one comment on the cassettes, I think it is rather unfortunate that the English reader cannot even pronounce the title "Gitanjali" correctly. This detracts from the otherwise positive impression made by your high production standards. I hope you will take this as a constructive comment from a well-wisher. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, Shashi Tharoor xecutive Assistant to the Secretary-General Mr. Alok Sanyal CD40, Sector 1 Salt Lake City Calcutta 700 064 INDIA M1BHH Alok Sanyal ph. D. Mailing Address : Department of Physics, Jadavpur University CD 40, SECTOR I SALT LAKE CITY W] CALCUTTA-700064 INDIA Telephone +91 33 337 5037/337 59U8 +91 33 U40 8656 UNITED N-ew Y*vK MY 10017 Indian poets especially the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lead the list of Asian writers who'have been most translated into the languages of the world. -

The Silver Series - 3

DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 6 - 10 JULY 2020 10% SALE PROCEEDS TO 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 THE SILVER SERIES EDITION 3 100 ARTISTS ² 100 WORKS Modern and Contemporary Indian Art 6 - 10 JULY 2020 FIXED-PRICE ONLINE SALE The Silver Series is DAG’s initiative towards raising funds for charity through its fixed-price online sales For further information please contact us at [email protected] 1 DAG : THE SILVER SERIES - 3 FROM ASHISH ANAND’S DESK Hundreds of great artists have marked every decade of the twentieth century, which is why I have always been surprised at the invisibility of so many of our masters. Painters, sculptors, printmakers, teachers, they have made a name for themselves, but in the absence of their work being shown nationally—rather than regionally, as has been the norm—many have remained outside mainstream discourse. At DAG, it has been our effort to ensure their rediscovery and recognition, something we continue to do with our Silver Series, fixed-price online sales. The outstanding success of the first two editions is an indicator that art-lovers also have an appreciation for lesser-known names, as well as those whose works do not appear frequently in the market. Our endeavour with every edition will be to continue to surprise you with the mix of artists and the quality of their work. I hope the additions in this edition will bring you joy. If you miss any favourites, I assure you that you will find them in subsequent editions. -

Overcoming Polarized Modernities: Counter-Modern Art Education: Santiniketan

Overcoming Polarized Modernities: Counter-Modern Art Education: Santiniketan, The Legacy of a Poet's School ABSTRACT Paul Gilroy identified counter cultures of modernity emerging in new-world African Diaspora communities in resistance, but not simply reactionary, to imperial modernity. This paper argues that Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University, founded in 1922 during the escalating struggle for Indian Independence, is similarly an example of counter-modernity. Tagore recognized that race, nationalism, materialism and an over- reliance on and abuse of science and technology, were central problems of European modernity’s notion of civilization and progress. In the new experiment in art education in Santiniketan Nandalal Bose and his fellow artist teachers incorporated an understanding of cultural distinctiveness, hybridity, selective disjunctures from, and continuities with, traditions into their pedagogy and art practice. The subtle persistence of modernist presumptions in postmodernity, make Tagore’s art education experiment, with its shortcomings, an important source of insight for overcoming imperial modernity’s subtle legacies. Art educators tend to focus on elementary and high school issues, yet a substantial portion of teacher training is in professional art classes. Art and teaching philosophies are intuitively learnt in the process. They are frequently tenacious and difficult to change, whether wrong or right. Yet they are not often the object of investigation by art educators, hence this essay. The model of university level art education developed in 1 Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University during the period 1919 – 1951 was in many ways unique for its time. That period coincides with Nandalal Bose’s tenure as Principal of Kala Bhavana (the Art Department), during which time the institution developed its aesthetic and pedagogy. -

Paula Sengupta

PAULA SENGUPTA (B. 1967, London) Lives and works in Kolkata EDUCATION 1993-2000 PhD in Printmaking, Department of Graphic Art, Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati, Santini-ketan 1990-92 MFA in Printmaking, Kala Bhavana, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan 1985-89 BFA in Painting, College of Art, New Delhi SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2013-14 Into Exile, Apparao Galleries, Chennai 2011 Lv, Pony, Gallery Espace, New Delhi 2010 Rivers of Blood, Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai 2009 Trousseau Tuck, Gallery Open-eyed Dreams, Kochi 2007 No.8 Shorts Bazaar/#8 Short Street? – The Nuptial Chamber, Akarprakar, Kolkata 2006 No.8 Shorts Bazaar/#8 Short Street?, Project 88, Mumbai 2004 Real & Constructed Memories, Right Lines Gallery, Bangalore 2001 Exhibition of Prints, Atelier 2221, New Delhi 2000 Exhibition of Prints, Nehru Centre, London 1999 Exhibition of Prints, Right Lines Gallery, Bangalore 1997 Exhibition of Prints and Collages, Russi Mody Centre for Excellence, Jamshedpur Exhibition of Drawings, Prints and Paintings, Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai 1995 Exhibition of Drawings, Prints and Paintings, Emerald Isle Gallery, Kolkata 1992 Exhibition of Prints, Triveni Kala Sangam, New Delhi 1990 Exhibition of Paintings, Alliance Francaise, Kolkata DUO 2018-19 Of herbariums, hortoriums and home by Nandini Bagla Chirimar & Paula Sengupta at Gallery Espace, New Delhi 2017 Himalayan Diaries by Sujoy Das & Paula Sengupta at The Z’s Precinct, Kolkata 2012 Exhibition design of Panchvastra by Ritu Kumar, Ritu Kumar, Kolkata 1999 Exhibition of Prints, Jamshedpur School of Art, Jamshedpur -

Press Release

Press Release www.akarprakar.com | [email protected]|Tel 011- 41315348 Preview: Tuesday, 23rd July 2019 l 6:00 pm-9:00 pm The Exhibition will be on view: 24thJuly - 16th August 2019, 11:00 am-7:00pm (Sunday and Public Holidays Closed) Venue: Akar Prakar, D 43, Defence Colony, First Floor, New Delhi-110024 Participating Artists: DHARMENDRA PRASAD I GOPA ROY I KOMPIRIBA I SISIRTHAPAITHLANA BAZIK I TREIBOR MAWLONG I VICTOR HAZRA I WAHIDA AHMED Curated by Zero Gravity Collective Akar Prakar Contemporary is pleased to showcase the exhibition A-PART: Stories of Lands and Lines a group show comprising the works of eight artists from the North East India including Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Sikkim and Tripura. Concept Note India’s North-East is immensely diverse in many ways, and the prime source of local identity is derived from tribal affiliation, and ethno-linguistic factors. The region is known for a multitude of conflicts and the geopolitical problems having both internal and external context. Border areas have their own peculiarities and intricacies; often vulnerable to some issues like indigenous identity, sovereignty, and in recent years a huge influx of illegal infiltration of population. These add up the pressure on their social, economic and environmental resources. What does it mean when we talk about “territory” today? The term does not simply refer to a geographical or spatial area; it carries an extensive horizon including social and cultural belongings and encompasses the personal, psychological and mental sphere. The works in the exhibition reflect different approaches, lifestyles and ways of perceiving the unstable relationship within the borders. -

NANDALAL BOSE the Doyen of Indian Art DINKAR KOWSHIK

NANDALAL BOSE The doyen of Indian art DINKAR KOWSHIK Contents Forebears and Parents School and College Education Nandalal enters the Magic Circle Early Laurels Discovery of Indian Art At Ajanta Okakura The Poet and the Painter Nandalal and Coomaraswamy Interim Ethical Moorings Far Eastern Voyage Wall Paintings Architecture & Museum Notes on His Paintings Art for the Community Depression Artist of the Indian National Congress A Humane and Kindly Being Nandalal and His Students Nandalal’s Views on Art Gandhiji’s Visit —1945 Admirers and Critics Evening Years I am indebted to the following scholars, authors, colleagues and relatives of Acharya Nandalal Bose for their assistance in assembling material for this book. Their writings and information given during personal interviews have been most helpful: Sri Banabehari Gosh, Sri Biswarup Bose, Sm. Gouri Bhanja, Sm. Jamuna Sen, Sri Kanai Samanta, Sri K.G. Subramanyan, Sri Panchanan Mandal, Sri Rabi Paul, Sri Sanat Bagchi, Sm. Uma Das Gupta, Sm. Arnita Sen. I am grateful to Sri Sumitendranath Tagore for his permission to reproduce Acharya Nandalal’s portrait by Abanindranath Tagore on the cover. I thank Dr. L.P. Sihare, Director, National Gallery of Modern Art, for allowing me to use photographs of Acharya Nandalal’s paintings from the collections in the National Gallery. I record my special gratitude to Sm. Jaya Appasamy, who went through the script, edited it and brought it to its present shape. Santiniketan 28 November 1983 DINKAR KOWSHIK Forebears and Parents Madho, Basavan, Govardhan, Bishandas, Mansur, Mukund and Manohar are some of the artists who worked in the imperial ateliers of Akbar and Jehangir. -

Estimates Committee ( 1 9 6 4 - 6 5 )

B .C . N o. 4x 4 ESTIMATES COMMITTEE ( 1 9 6 4 - 6 5 ) EIGHTY -THIRD REPORT (THIRD LOK SABHA') MINISTRY OF EDUCATION VISVA-BHARATI UNIVERSITY I. OK SABHA SECRETARIAT N EW D E L H I AxtriU 1965 VaimaMha, 1&87 (SaMa) P rice : Rs. X * xo Pais* LIST OF AUTHORISED AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT PUBLICATIONS SI. Name of Agent Agency Si. Name of Agent Agency No* No. No. No. ANDHRA PRADESH 11. Charles Lambert and Company, io i, Mahatma i. Andhra University Gene Gandhi Road, ral Cooperative Stores Opp. Clock Tower, Ltd., Waltair (Visakha- Fort, Bombay . 30 patnam) . 8 12. The Current Book House, 2. G. R. Lakshmipathy Maruti Lane, Raghu- Chetty & Sons, General nath Dadaji Street, Merchants & News Bombay-i . 60 Agents, Newpet, Chandragiri, Chittoor 13. Deccan Book Stall, Fergu District . 94 son College Road, Poona-4 . 65 ASSAM RAJASTHAN 3. Western Book Depot, Pan 14. Information Centre, Bazar, Gauhati. 7 Govt, of Rajasthan, Tripolia, Jaipur City. 38 BIHAR UTTAR PRADESH 4. Amar Kitab Ghar, Post i$. Swastik Industrial Works, Box 78, Diagonal Road, <>9, Holi Street, Meerut Jamshedpur. 37 City . * 16. Law Book Company, GUJARAT Sardar Patel Marg, Allahabad-1 48 j. Vijay Stores, Station Road, Anand* . 35 WEST BENGAL 6. The New Order Book 17. Granthaloka, 5/1, Ambica Company, Ellis Bridge, Mookherjee Road, Ahmedabad-6. 63 Belgharia, 24 Paragnas. 10 MADHYA PRADESH 18. W. Newman & Company Limited, 3, Old Court House Street, Calcutta. 44 7. Modem Book House, Shiv Vilas Palace, Indore city. 19. Firma K. L. Mukho- 13 padhyay, 6/1A, Ban- chharam Akrur Lane, Calcutta-12 82 MAHARASHTRA 8.