Overcoming Polarized Modernities: Counter-Modern Art Education: Santiniketan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 5 Article 2 Issue 2 South - South Axes of Global Art 2016 Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond YIN KER School of Art, Design & Media, Nanyang Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Art Education Commons, Art Practice Commons, Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Other International and Area Studies Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation KER, YIN. "Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond." Artl@s Bulletin 5, no. 2 (2016): Article 2. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. South-South Śāntiniketan and Modern Southeast Asian Art: From Rabindranath Tagore to Bagyi Aung Soe and Beyond Yin Ker * Nanyang Technological University Abstract Through the example of Bagyi Aung Soe, Myanmar’s leader of modern art in the twentieth century, this essay examines the potential of Śāntiniketan’s pentatonic pedagogical program embodying Rabindranath Tagore’s universalist and humanist vision of an autonomous modernity in revitalizing the prevailing unilateral and nation- centric narrative of modern Southeast Asian art. -

Kala Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Under Graduate Syllabus, Objectives and Outcomes (Cbcs)

DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN (CERAMIC & GLASS) KALA BHAVANA, VISVA-BHARATI UNDER GRADUATE SYLLABUS, OBJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES (CBCS) The four years Undergraduate BFA programme at Kala Bhavana begins with a 1-year Foundation Course. In the foundation course, the students get introduced with all discipline of visual art. Foundation course is followed by three years of specialization in Department of Design (Ceramic & Glass) I. Department of Design (Ceramic & Glass) component in the 1 year BFA Foundation programme Programme & Course Name Course Content Objective Expected Outcome Semester and Credits 1st. Year BFA – BFA/CG-F 1 It enhances /helps students to understand their In outdoor studies, students use very many Foundation 2 credits 1. Nature study on paper and immediate surroundings in the context of different traditional mediums and methods (Integrated basic understanding of observations of certain images and experiences which also help them to execute or approach Course) Ceramics ‘pottery/images they are gaining, more closely. They learn to images in multiple manners. articulate the use of lines, colours, shapes and Finally and most importantly they observe ST in coiling technique 1 . Semester forms of different given images around them. Also certain images around them and try to execute Course Name: (earthen ware). grows an understanding of different things from in different mediums, get attached to their BFA/CG-F 1, 2 Study of traditional daily observations, which gradually used in present situations and understand their own Course Credit: 2 terracotta forms and compositions. presence. Duration 90 Days copying in clay (earthen Learns multiple shapes, quality of objects, To develop their observation power/quality, (July to ware). -

National Gallery of Modern Art New Delhi Government of India Vol 1 Issue 1 Jan 2012 Enews NGMA’S Newsletter Editorial Team From

Newsletter JAN 2012 National Gallery of Modern Art New Delhi Government of India Vol 1 Issue 1 Jan 2012 enews NGMA’s Newsletter Editorial Team FroM Ella Datta the DIrector’s Tagore National Fellow for Cultural Research Desk Pranamita Borgohain Deputy Curator (Exhibition) Vintee Sain Update on the year’s activities Assistant Curator (Documentation) The NGMA, New Delhi has been awhirl with activities since the beginning of the year 2011. Kanika Kuthiala We decided to launch a quarterly newsletter to track the events for the friends of NGMA, Assistant Curator New Delhi, our well-wishers and patrons. The first issue however, will give an update of all the major events that took place over the year 2011. The year began with a bang with the th Monika Khanna Gulati, Sky Blue Design huge success of renowned sculptor Anish Kapoor’s exhibition. The 150 Birth Anniversary of Design Rabindranath Tagore, an outstanding creative genius, has acted as a trigger in accelerating our pace. NGMA is coordinating a major exhibition of close to hundred paintings and drawings Our very special thanks to Prof. Rajeev from the collection of NGMA as well as works from Kala Bhavana and Rabindra Bhavana of Lochan, Director NGMA without whose Visva Bharati in Santiniketan, West Bengal. The Exhibition ‘The Last Harvest: Rabindranath generous support this Newsletter would not Tagore’ is the first time that such a major exhibition of Rabindranath’s works is travelling to have been possible. Our Grateful thanks to all so many art centers in Europe and the USA as well as Seoul, Korea. -

Raja Ravi Varma 145

viii PREFACE Preface i When Was Modernism ii PREFACE Preface iii When Was Modernism Essays on Contemporary Cultural Practice in India Geeta Kapur iv PREFACE Published by Tulika 35 A/1 (third floor), Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110 049, India © Geeta Kapur First published in India (hardback) 2000 First reprint (paperback) 2001 Second reprint 2007 ISBN: 81-89487-24-8 Designed by Alpana Khare, typeset in Sabon and Univers Condensed at Tulika Print Communication Services, processed at Cirrus Repro, and printed at Pauls Press Preface v For Vivan vi PREFACE Preface vii Contents Preface ix Artists and ArtWork 1 Body as Gesture: Women Artists at Work 3 Elegy for an Unclaimed Beloved: Nasreen Mohamedi 1937–1990 61 Mid-Century Ironies: K.G. Subramanyan 87 Representational Dilemmas of a Nineteenth-Century Painter: Raja Ravi Varma 145 Film/Narratives 179 Articulating the Self in History: Ghatak’s Jukti Takko ar Gappo 181 Sovereign Subject: Ray’s Apu 201 Revelation and Doubt in Sant Tukaram and Devi 233 Frames of Reference 265 Detours from the Contemporary 267 National/Modern: Preliminaries 283 When Was Modernism in Indian Art? 297 New Internationalism 325 Globalization: Navigating the Void 339 Dismantled Norms: Apropos an Indian/Asian Avantgarde 365 List of Illustrations 415 Index 430 viii PREFACE Preface ix Preface The core of this book of essays was formed while I held a fellowship at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library at Teen Murti, New Delhi. The project for the fellowship began with a set of essays on Indian cinema that marked a depar- ture in my own interpretative work on contemporary art. -

Contextual Modernism’ in the Silk Paintings of Maniklal Banerjee

The Chitrolekha Journal on Art and Design (E-ISSN 2456-978X), Vol. 1, No. 2, 2017 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/cjad.12.v1n205 PDF URL: www.chitrolekha.com/ns/v1n2/v1n205.pdf The ‘Contextual Modernism’ in the Silk Paintings of Maniklal Banerjee Ashmita Mukherjee Research Scholar, Jadavpur University. Email: [email protected] Abstract The paper tries to analyze the silk paintings of Maniklal Banerjee (1917-2002) who was greatly influenced by the artists of the so-called Bengal school of art. The school started by Abanindranath Tagore did not remain confined to its own time and space, but grew into dynamic new modernisms over a span of nearly a century. Art historian Sivakumar invoked a number of artists of Santiniketan and called it a “contextual modernism”. The paper tries to re-read the spirit of Santiniketan artists on the more recent and un- researched art of Maniklal Banerjee- who contextualized in his own way the Bengal ‘school’ that had by now turned into a ‘movement’. The spirit of freedom runs at the core of this movement and finds a new language in the late twentieth century artist’s renderings of daily life and Puranic narrations. Keywords: Bengal School, Maniklal Banerjee, Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Indian art, Puranic art, aesthetics Introduction: Maniklal Banerjee (1917-2002) Barely remembered beyond textbooks of art schools, Maniklal Banerjee was one of the first innovators of the technique of using water-color on silk in India. In order to engage in any critical discussion on his works, it is ironical that this painter- a recipient of the prestigious Abanindra Puraskar in 1999- needs an introduction (Plate 1 and 2). -

Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 ANNUAL Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 © Gandhi and People Gathering by Shri Upendra Maharathi Mahatma Gandhi by Shri K.V. Vaidyanath (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) (Courtesy: http://ngmaindia.gov.in/virtual-tour-of-bapu.asp) ANNUAL REPORT 2019-2020 Gandhi Smriti and Darshan Samiti ANNUAL REPORT - 2019-2020 Contents 1. Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 03 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 05 3. Structure of the Samiti.................................................................................................. 13 4. Time Line of Programmes............................................................................................. 14 5. Tributes to Mahatma Gandhi......................................................................................... 31 6. Significant Initiatives as part of Gandhi:150.................................................................. 36 7. International Programmes............................................................................................ 50 8. Cultural Exchange Programmes with Embassies as part of Gandhi:150......................... 60 9. Special Programmes..................................................................................................... 67 10. Programmes for Children............................................................................................. -

The Nandalal—Gandhi—Rabindranath Connection

The Nandalal—Gandhi—Rabindranath Connection Nandalal Bose’s ideas on art and art education were influenced to a large extent by the ideas of two of his distinguished contemporaries—Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore. Gandhi is known in India today as the father of the nation as he managed to awaken almost single-handedly, the aspirations of the Indian people on a wide scale and organize them into a formidable political force. He had captured their attention even before he entered the country’s political scene by his successful use of satyagraha (non-violent political action) in South Africa to secure for its coloured people some measure of social justice from its white rulers. This was so unprecedented that it became the talk of the whole world. Gandhi moved to India in 1915; and in the next three decades used the same agitational strategy to emancipate the country from colonial rule. Nandalal was an involved witness of this process and soon became one of his great admirers. He became particularly so when Gandhi’s action programme widened its purview to include the economic independence of India and the strengthening of its wide-spread artisan traditions to achieve this. This focus on the artisan traditions had a special appeal for Nandalal. Even in his childhood years the artisan’s workshops in his home town had a great attraction for him; he often went there to watch the workers—potters, woodworkers, metal smiths, scroll-painters—ply their trades with seemingly effortless skill with open-eyed fascination. It was this fascination that fed his desire to become an artist when he grew up. -

Download Excerpt

the art of the art of CONTENTS January – March 2012 Director’s Note 5 © 2012 Delhi Art Gallery Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi Editor’s Note 7 White, Black And Grey: 10 The Colonial Interface Paula Sengupta ‘Revivalism’ And The 32 11 Hauz Khas Village, New Delhi 110016, India ‘Bengal School’ Tel: 91 11 46005300 Sanjoy Mallik DLF Emporio, Second Floor, Vasant Kunj New Delhi 110070, India History And Utopia 44 Tel: 91 11 41004150 Ina Puri Email: [email protected] www.delhiartgallery.com Late 18th Century -1910 62 PROJECT EDITOR: Kishore Singh 1911-1920 103 EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Shruti Parthasarathy PROJECT COORDINATOR: Nishant and Neha Berlia 1921-1930 120 RESEARCH: Aditya Jha, Puja Kaushik, Poonam Baid, Sukriti Datt 1931-1940 140 PHOTOGRAPHY OF ARTWORKS: Durga Pada Chowdhury 1941-1950 164 RESTORATION: Priya Khanna 1951-1960 208 DESIGN: Madhav Tankha, Vivek Sahni – Vivek Sahni Design 1961-1970 252 PRINT: Archana Printers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi 1971-1980 298 All rights are reserved under international copyright conventions. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, 1981-1990 340 electronic and mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing 1991-2010 368 from the publisher. 2000-2010 400 ISBN: 978-93-81217-23-8 Artist Profiles 415 Front cover: Author Profiles 452 Back cover: Artist Groups in Bengal 453 Bibliography 454 Artist Index 461 DIRECTOR’S NOTE engal – the association with its art (and literature, and cinema, and food) is instinctive, almost as if it’s DNA-coded into its people. -

Download PDF « Kapila Vatsyayan : a Cognitive Biography: a Float A

Q1FFTQGILORF # Kindle // Kapila Vatsyayan : A Cognitive Biography: A Float a Lotus Leaf Kapila Vatsyayan : A Cognitive Biography: A Float a Lotus Leaf Filesize: 5.23 MB Reviews These sorts of book is the greatest book offered. This can be for all those who statte that there had not been a really worth reading. I am just quickly could get a pleasure of reading a written ebook. (Verner Goyette DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GILPORKS6UEM « Kindle ~ Kapila Vatsyayan : A Cognitive Biography: A Float a Lotus Leaf KAPILA VATSYAYAN : A COGNITIVE BIOGRAPHY: A FLOAT A LOTUS LEAF Stellar Publishers, 2015. Hardcover. Book Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Contents: 1. Rock salt of character. 2. An era of eclectic minds. 3. Not a generation of midnights children. 4. Intellectual validity came from foreign shores. 5. Southern sojourn and other paradoxical journeys. 6. Dance became her Talisman. 7. Banaras a boat ride of relearning. 8. In the corridors of bureaucracy. 9. Maulana Sahabs Deep commitment to heritage. 10. The arts as pedagogical tool. 11. Almora was a primordial call. 12. Intra-cultural dialogues. 13. Maiden oriental discourse in the orient. 14. Gita Govinda-a fathomless discovery. 15. Revival of Buddhist and Sanskrit studies. 16. Institutions outlast the individuals. A life beyond categories perhaps thats the quintessence of Dr. Kapila Vatsyayans trajectory both as a sensitive artist and profound scholar. She has not only questioned, but also defied the mindsets that create those categories, with her multidisciplinary approach. Given her proximity to the stalwarts of the intellectual and cultural arena, i.e. Aruna Asaf Ali, Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, Rukmini Devi Arundale, Dr. -

India Pavilion Opening Release Final

India Pavilion 58th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia SHAKUNTALA KULKARNI Photo Performance: Asiatic Library, 2010 –2012 Digital print on rag paper 28 x 42 inches Collection: Chemould Prescott, Mumbai Image courtesy: Artist Our Time for a Future Caring Exhibition: 11 May to 24 November 2019 Pre-opening: 8-10 May 2019 (opening India Pavilion: 8 May, 12:30pm) Organisers: Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India and Confederation of Indian Industry Commissioner: National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi Principal Partner & Curator: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art The India Pavilion presentation Our Time for a Future Caring at the 58th International Art Exhibition – La biennale di Venezia opens to the public on 11 May 2019. Our Time for a Future Caring, a group exhibition curated by Roobina Karode, Director and Chief Curator at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, critically engages with the figure and philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi, reflecting on his enduring impact and the contemporary relevance of his ideals. Gandhi acts as focal point for different artistic interpretations, delving into broader issues of India’s history and nationhood, as well more conceptual investigations into notions of freedom, nonviolence, action and agency. The exhibition forms part of India’s celebrations of ‘150 years of Gandhi’ and showcases artworks spanning from the twentieth century to the present day by Nandalal Bose, MF Husain, Atul Dodiya, Jitish Kallat, Ashim Purkayastha, Shakuntala Kulkarni, Rummana Hussain and GR Iranna. A landmark partnership between India’s public and private sectors has enabled India’s second national participation at the Biennale Arte 2019. The Pavilion was organized by the India Ministry of Culture with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools ICELAND 001041 Haskoli Islands 046908 Icelandic Col Social Pedagogy 001042 Kennarahaskoli Islands 002521 Taekniskoli Islands 002521 Technical College Iceland 001042 Univ Col Education Iceland 001041 Univ Iceland INDIA 000702 A Loyola Col 000678 Abhyuday Skt Col 000705 Ac Col 000705 Ac Col Commerce 000705 Ac Training Col 000629 Academy Of Architecture 000651 Acharatlal Girdharlal Teachers 000705 Acharya Brajendra Nath Seal Co 000701 Acharya Thulasi Na Col Commerc 000715 Adarsh Degree Col 000707 Adarsh Hindi Col 000715 Adarsh Vidya Mandir Shikshak 000710 Adarsha Col Ed 000698 Adarsha Ed Societys Arts Sci C 000710 Adhyapak Col 000701 Adichunchanagiri Col Ed 000701 Adichunchanagiri Inst Tech 000678 Adinath Madhusudan Parashamani 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Bhil 000651 Adivasi Arts Commerce Col Sant 000732 Adoni Arts Sci Col 000710 Ae Societys Col Ed 000715 Agarwal Col 000715 Agarwal Evening Col 000603 Agra University 000647 Agrasen Balika Col 000647 Agrasen Mahila Col 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Coimbat 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Killiku 000734 Agri Col Research Inst Madurai 000710 Agro Industries Foundation 000651 Ahmedabad Arts Commerce Col 000651 Ahmedabad Sci Col 000651 Ahmedabad Textile Industries R 000710 Ahmednagar Col 000706 Aizwal Col 000726 Aja Col 000698 Ajantha Ed Societys Arts Comme 000726 Ajra Col 000724 Ak Doshi Mahila Arts Commerce 000712 Akal Degree Col International Schools 000712 Akal Degree Col Women 000678 Akhil Bhartiya Hindi Skt Vidya 000611 Alagappa College Tech, Guindy 002385 -

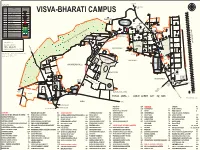

Updated Campus Map in PDF Format

KOPAI RIVER N NE LEGEND : NW E PRANTIK STATION W 1.5 KM SL. NO. NAME SYMBOL SE WS 1. HERITAGE BUILDING S 2. ADMIN. BUILDING VISVA-BHARATI CAMPUS 3. ACADEMIC BUILDING 42 4. GUEST HOUSE G 5. AUDITORIUM / HALL 101 6. HOSTEL BUILDING DEER PARK 44 7. CANTEEN C G RATAN PALLI 8. HOSPITAL LAL BANDH 01 41 SHYAMBATI 43 40 9. WATER BODY G 39 KALOR DOKAN 10. SWIMMING POOL 45 11. PLAY GROUND 38 93 91 90 UTTARAYANA/ 48 12. AGRICULTURE FARM RABINDRA BHAVANA 34 OLD MELA GROUND 94 POND (JAGADISH KANAN) 37 35 02 13. VILLAGE 33 47 T 98 92 46 G C T A T 14. WILDLIFE SANCTUARY 96 89 52 53 54 36 PM HOSPI AL 97 SIKSHA BHAVANA COMPLEX 50 51 04 E S A U R Y 100 03 15. ROAD 58 55 G SEVA PALLI 32 99 95 31 G 16. V.B.PROPERTY LINE D L F N PRATI ICH SRIPALLI SANGIT 60 KALA BHAVANA 57 LIPIKA I L I BHAVANA 56 30 N R LW E KALIGUNJE PEARSON PALLI 49 59 AMRAKUNJA 141 66 61 64 63 C 29 65 27 28 76 77 62 PATHA BHAVANA AREA NT LCERA L A 74 AY 68 75 LI RBR 103 67 EASTER AILIN AY PREPARED BY:- B A L V P U R W 25 78 102 F E PURVA PALLI C CENTRAL O FIC POUS MELA GROUND ESTATE OFFICE, SU 3 79 ASRAMA 80 26 73 81 RI 0 KM PLAY GROUND 24 VISVA - BHARATI 69 23 05 SIMANTAPALLI 83 22 SANTINIKETAN, PIN-731235 72 88 82 PLAY HATIPUKUR GROUND 85 84 SBI AUROSRI MARKET 21 86 71 LEGAL DISCLAIMER : THIS IS AN INDICATIVE MAP ONLY, 20 HATIPUKUR 70 16 FOR THE AID OF GENERAL PUBLIC.