Steering the Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eighth Grade

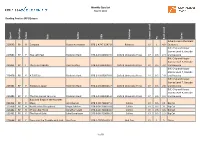

Bibliography for Sheila Goeke 5/4/15 10:16 AM Bibliography Sorted by Author / Title. J F ALE Alexander, Kwame. The crossover. Fourteen-year-old twin basketball stars Josh and Jordan wrestle with highs and lows on and off the court as their father ignores his declining health. J 370.193 BEA Beals, Melba. Warriors don't cry : a searing memoir of the battle to integrate Little Rock's Central High. New York, N.Y. : Pocket Books, c1994. A memoir of the battle to integrate the Little Rock Central High School following the 1954 Supreme Court ruling. YA J F BEL Bell, Hilari. The last knight. 1st ed. New York, NY : Eos, c2007. In alternate chapters, eighteen-year-old Sir Michael Sevenson, an anachronistic knight errant, and seventeen-year-old Fisk, his street-wise squire, tell of their noble quest to bring Lady Ceciel to justice while trying to solve her husband's murder. J B JOBS Blumenthal, Karen. Steve Jobs : the man who thought different : a biography. 1st ed. New York : Feiwel & Friends, 2012. Chronicles the life and accomplishments of Apple mogul Steve Jobs, discussing his ideas, and describing how he has influenced life in the twenty-first century. J F BOD Bodeen, S. A. (Stephanie A.) , 1965-. The compound. 1st ed. New York : Feiwel and Friends, 2008. After his parents, two sisters, and he have spent six years in a vast underground compound built by his wealthy father to protect them from a nuclear holocaust, fifteen-year-old Eli, whose twin brother and grandmother were left behind, discovers that his father has perpetrated a monstrous hoax on them all. -

Contenidos 28 De Nov Al 04 De Diciembre De 2020 Boletín #379

CONTENIDOS 28 DE NOV AL 04 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2020 BOLETÍN #379 TEMA DE LA SEMANA: Iglesias, Feministas y activistas contra la violencia de género ................................ 4 1. Se insta a los líderes religiosos africanos a redoblar los esfuerzos contra la violencia de género ...................................... 4 2. Iglesias cubanas se mantienen en campaña por la No violencia hacia mujeres y niñas ..................................................... 5 3. Wikiclaves Violeta: activismo contra la violencia de género ................................................................................................. 5 4. La impunidad juega en contra en el combate a la violencia de género: ONU ...................................................................... 6 5. Crece la violencia de género: Sánchez Cordero .................................................................................................................. 6 6. Son ―insuficientes‖ las estrategias del Estado contra los feminicidios: CNDH ..................................................................... 7 7. Solicitud de día nacional de feminicidio divide las opiniones ............................................................................................... 7 8. ―La lucha feminista es una lucha por la sociedad‖ ................................................................................................................ 8 9. Reivindicaciones feministas: Gloria Muñoz Ramírez ........................................................................................................... -

Qu Iz # Qu Iz Typ E Fictio N Title Auth O R ISBN Pu B Lish Er in Terest Level

Monthly Quiz List March 2016 Reading Practice (RP) Quizzes Quiz # Quiz Type Fiction Title Author ISBN Publisher Interest Level Pts Level Book Series Adventures in the Great 229693 RP N Camping Robyn Hardyman 978-1-4747-1547-8 Raintree LY 1 4.9 Outdoors Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 6, Decode 229583 RP F Two Left Feet Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830017-5 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.4 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229491 RP F The Time Capsule Paul Shipton 978-0-19-830028-1 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 3.2 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229478 RP F A Tall Tale Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830029-8 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.9 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229481 RP F Holiday in Japan Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830026-7 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.8 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 9, Decode 229485 RP F The Fair-Haired Samurai Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830041-0 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 3.3 and Develop Buzz and Bingo in the Monster 223452 RP F Maze Alan Durant 978-0-00-718617-4 Collins LY 0.5 3.1 Big Cat 223458 RP N Pacific Island Scrapbook Angie Belcher 978-0-00-718619-8 Collins LY 0.5 3.1 Big Cat 223442 RP N Africa's Big Three Jonathan Scott 978-0-00-718693-8 Collins LY 0.5 3.6 Big Cat 223461 RP F The Pot of Gold Julia Donaldson 978-0-00-718696-9 Collins LY 0.5 2.3 Big Cat 229648 RP F Daisy and the Trouble with Jack Kes Gray 978-1-78295-630-3 Red Fox LY 1 5 Daisy 1 of 9 The LEGO Movie: Calling All 229723 RP F Master Builders! David -

Cosmopolitan Ethics and the Limits of Tolerance: Representing the Holocaust in Young Adult Literature

COSMOPOLITAN ETHICS AND THE LIMITS OF TOLERANCE: REPRESENTING THE HOLOCAUST IN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE Rachel L. Dean-Ruzicka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Beth Greich-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Nancy W. Fordham Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Kimberly Coates Dr. Vivian Patraka © 2011 Rachel L. Dean-Ruzicka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Beth Greich-Polelle, Advisor This dissertation critically evaluates the concepts of tolerance and toleration and how these two ideas are often deployed as the appropriate response to any perceived difference in American culture. Using young adult literature about the Holocaust as a case study, this project illustrates how idealizing tolerance merely serves to maintain existing systems of power and privilege. Instead of using adolescent Holocaust literature to promote tolerance in educational institutions, I argue that a more effective goal is to encourage readers’ engagement and acceptance of difference. The dissertation examines approximately forty young adult novels and memoirs on the subject of the Holocaust. Through close readings of the texts, I illustrate how they succeed or fail at presenting characters that young adults can recognize as different from themselves in ways that will help to destabilize existing systems of power and privilege. I argue this sort of destabilization takes place through imaginative investment with a literary “Other” in order to develop a more cosmopolitan worldview. Using the theories of Judith Butler, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Gerard Delanty I contended that engagement with and appreciation of difference is possible when reading young adult Holocaust literature. -

Sachbuch Literatur

AUFBAU A HERBST 2021 LITERATUR U SACHBUCH F B A U Unsere SPIEGEL- Bothor Mathias © Bestseller – wir danken Ihnen für Ihre Liebe Kolleginnen und Unsere Unterstützung! Kollegen im Handel, BESTSELLER bevor wir Ihnen unsere neuen Bücher vorstellen, »›Kindheit‹, ›Jugend‹ und möchte ich mich bedanken für ein Frühjahr, in dem ›Abhängigkeit‹ sind von atem- Sie trotz widriger Umstände – geschlossene Buch- handlungen, Lockdown und die Sorge darum, wie »Mit Diskriminierung beraubender Intensität und und vor allem wann eine Art von Normalität wieder und Unterdrückung Schönheit. Aus dem Staub ihres möglich sein wird – so viele unserer Bücher zu großen Lebens leuchtet dieses Werk: Erfolgen gemacht haben. beschäftigt sich die Jour- Die dänische Autorin Tove Ditlevsen, deren außeror- »Wer sich von Roig über nalistin und ARD-Tages- Tove Ditlevsen gilt es unbedingt dentliche Kopenhagen-Trilogie Sie mit uns zusammen die Wirklichkeit aufklären themen-Kommentatorin wiederzuentdecken.« entdeckt haben, schreibt im dritten Band »Abhängig- lässt, findet sich in Natalie Amiri, die zu den SPIEGEL ONLINE keit«: »Aber für mich ist das Leben nur ein Genuss, wenn ich schreiben kann.« So unverstellt und direkt, den künftigen Debatten »Osang kann einfach intimen Kennerinnen des so kompromisslos und zärtlich zugleich war selten ein besser zurecht.« fantastisch schreiben.« heutigen Iran gehört.« Blick auf das eigene Leben, und die Radikalität und DER SPIEGEL DIE ZEIT SÜDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG Intensität ihrer Schilderungen hat durch Sie und mit Ihnen ein großes Publikum begeistert. Die Macht der Literatur haben viele von uns in diesen Monaten erlebt, in denen Bücher zu Brücken wurden und uns befreit haben aus der Enge einer plötzlich begrenzten Welt. Wir brauchen Geschichten, wir leben in den eigenen Erzählungen ebenso wie in denen der anderen. -

Download 2020 Iread Resource Guide Home Edition

iREADiREAD HOMEHOME EDITIONEDITION 20202020 2021iREAD Summer Reading The theme for iREAD’s 2021 summer reading program is Reading Colors Your World. The broad motif of “colors” provides a context for exploring humanity, nature, culture, and science, as well as developing programming that demonstrates how libraries and reading can expand your world through kindness, growth, and community. Readers will be encouraged to be creative, try new things, explore art, and find beauty in diversity. Illustrations and posters tell the story: Read a book and color your world! Artwork ©2019 Hervé Tullet [www.sayzoop.com] for iREAD®. iREAD® (Illinois Reading Enrichment and Development) is an annual project of the Illinois Library Association, the voice for Illinois libraries and the millions who depend on them. It provides leadership for the development, promotion, and improvement of library services in Illinois and for the library community in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all. The goal of this reading program is to instill the enjoyment of reading and to promote reading as a lifelong pastime. Dig Deeper: Read, Investigate, Discover; Reading Colors Your World and all associated materials ©2019 Illinois Library Association. DIG DEEPER: READ, INVESTIGATE, DISCOVER 2020 iREAD® Resource Guide Portia Latalladi 2020 iREAD® Chair Alexandra Annen 2021 iREAD® Chair Becca Boland 2022 iREAD® Chair Brandi Smits 2020 iREAD® Ambassador Sarah Rice Resource Guide Coordinator David Roberts Pre-K Program Illustrator Rafael López Children’s Program Illustrator Alleanna Harris Young Adult Program Illustrator Jingo de la Rosa Adult Program Program Illustrator Diane Foote Executive Director, Illinois Library Association A PRODUCTION OF THE ILLINOIS LIBRARY ASSOCIATION Table of Contents Table of Contents 1. -

Comics and Graphic Novels for Young People

27 SPRING 2010 Going Graphic: Comics and Graphic Novels for Young People CONTENTS Editorial 2 ‘Remember Me’: An Afrocentric Reading of CONFERENCE ARTICLES Pitch Black 14 Kimberley Black The State of the (Sequential) Art?: Signs of Changing Perceptions of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels and the Holocaust 15 Graphic Novels in Britain 3 Rebecca R. Butler Mel Gibson Copulating, Coming Out and Comics: The High From Tintin to Titeuf: Is the Anglophone Market School Comic Chronicles of Ariel Schragg 16 too Tough for French Comics for Children? 4 Erica Gillingham Paul Gravett Is Henty’s History Lost in Graphic Translation? The Short but Continuing Life of The DFC 5 Won by the Sword in 45 pages 17 David Fickling Rachel Johnson Out of the Box 6 Sequences of Frames by Young Creators: The Marcia Williams Impact of Comics in Children’s Artistic Development 18 Raymond Briggs: Blurring the Boundaries Vasiliki Labitsi among Comics, Graphic Novels, Picture Books and Illustrated Books 7 ‘To Entertain and Educate Young Minds’: Janet Evans Graphic Novels for Children in Indian Publishing 19 Graphic Novels in the High-School Malini Roy Classroom 8 Bill Boerman-Cornell Strangely Familiar: Shaun Tan’s The Arrival and the Universalised Immigrant Experience 20 Britain’s Comics Explosion 9 Lara Saguisag Sarah McIntyre Journeys in Time in Graphic Novels from Reading between the Lines: The Subversion of Greece 21 Authority in Comics and Graphic Novels Mariana Spanaki Written for Young Adults 10 Ariel Kahn Crossing Boundaries 22 Emma Vieceli Richard Felton Outcault and The Yellow Kid 10 Dora Oronti Superhero Comics and Graphic Novels 22 Jessica Yates As Old as Clay 11 Daniel Moreira de Sousa Pinna Composing and Performing Masculinities: Of Reading Boys’ Comics c. -

Literary Plastination: from Body’S Objectification to the Ontological Representation of Death, Differences Between Sick-Literature and Tales by Amateur Writers

LITERARY PLASTINATION: FROM BODY’S OBJECTIFICATION TO THE ONTOLOGICAL REPRESENTATION OF DEATH, DIFFERENCES BETWEEN SICK-LITERATURE AND TALES BY AMATEUR WRITERS INES TESTONI GIULIA PARISE UNIVERSITY OF PADOVA EMILIO PAOLO VISINTIN UNIVERSITY OF LAUSANNE ADRIANO ZAMPERINI LUCIA RONCONI UNIVERSITY OF PADOVA This article presents a qualitative analysis of published and unpublished texts, aimed to understand a new narrative phenomenon named “sick-lit.” This is a genre of stories, written by professional novel- ists, rooted in disease, self-harm, suicide, sufferance from violence, death, and dying. In the Internet it has been considered as a trivialization of serious issues and even potentially encouraging readers to harm themselves. Our hypothesis is that this negative judgment is based on the ontological representa- tion of death and the objectification of the body depicted in these stories. In order to inquire into this possibility and to compare this anomalous form of story-telling with another kind of narration reflect- ing the wider common sensibility, a qualitative analysis was realized on six sick-lit novels (SLNs) and 21 unpublished tales written by amateur writers (AWTs). The results confirm the hypothesis: the SLNs represent death also as an absolute annihilation and the body is always reified through medical lan- guage, while the AWTs represent death only as a passage or reincarnation and the description of the de- teriorated body is minimal. Key words: Sick-lit; Ontological representation of death; Plastination; Death education; Grounded Theory Model. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ines Testoni, Department FISPPA – Section of Ap- plied Psychology, University of Padova, Via Venezia 8, 35131 Padova, Italy. -

2021 Texas Topaz Youth Nonfiction Reading List

2021 Texas Topaz Youth Nonfiction Reading List The purpose of the Texas Topaz Reading List is to provide children and adults with recommended nonfiction titles that stimulate reading for pleasure and personal learning. It is intended for recreational reading and is not designed to support any particular curriculum. Due to the diversity in age range and topics, Texas librarians should consider titles on this list in accordance with their own local collection development policies. (*) denotes a unanimous vote by the committee. K – 2nd *A Garden in Your Belly: Meet the Microbes in Your Gut by Masha D'Yans (Millbrook Press, 2020) A fascinating look at an essential part of our physiology, the human microbiome. Written in an accessible style for younger readers and illustrated with charming watercolors, this title also includes a glossary and a slew of gut-related facts. All the Way to the Top by Annette Bay Pimentel, illustrated by Nabi Ali (Sourcebooks Explore, 2020) Social justice is also a fight for kids, as demonstrated in this book by its fearless protagonist, Jennifer Keelen, who knew her voice would represent the thousands of handicapped kids like herself. Sure, it was an obstacle, but her wheelchair didn’t define her enthusiasm to accomplish the many goals on her list. This story of determination introduces kids to the history of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Brave Ballerina: The Story of Janet Collins by Annette Bay Pimentel, illustrated by Nabi Ali (Sourcebooks Explore, 2019) This picture book biography introduces Janet Collins, a Black dancer in the 1930s and 40s who ultimately, through hard work, determination, and encouragement from others, became the first Black prima ballerina to perform at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1951. -

Hullabaloo15

Welcome... ...to this autumn‐inspired issue of Hullabaloo! With the nights drawing in it’s the perfect time to catch up on some reading. Why not try one of the books featured inside? We’ve got Anthony Browne, the shortlisted titles for two Lincolnshire book awards, Neil Gaiman, The Gruffalo, and all the usual recent prizewinners. Or maybe you’ll be inspired by our nipper to go out and buy a comic! If all else fails you’re bound to find something on one of the chronologies mentioned in the article below. Happy Reading! Emma & Janice A Helping Hand In her role as a children’s literature librarian Janice is frequently asked for advice on finding particular types of books, like ones on specific themes, ones published in particular decades, ones for boys or teenagers, or just really good reads. We know it can be a bit of a challenge to know which books to choose so over the past couple of years we’ve put together several booklists to help you make more informed choices. For advice on the classics check out our two chronologies: the Chronology of Classic Picture Books and the Chronology of Classic Children’s Literature. Both feature books published over many decades and all of the books can be found in our library. For books featuring disability or family diversity try the two reading resources we produced in conjunction with Dr Richard Woolley and his BA Primary Education with QTS students: the Disability Reading Resource (new this year) and the Family Diversity Reading Resource (which was featured in our January 2008 issue). -

The Impact of Guns on Women' S Lives

The impact of guns on women’s lives [Back cover text] Countless women and girls have been shot and killed or injured in every region of the world. Millions more live in fear of armed violence against women. Two key factors lie at the heart of these abuses: the proliferation and misuse of small arms and deep-rooted discrimination against women. Armed violence against women is not inevitable. In many countries women have become powerful forces for peace and human rights in their communities. Their actions show how real change can be effected and women's lives made safer. Each of us can help put an end to the abuses highlighted in this report by joining the international campaigns to Stop Violence Against Women and to Control Arms. This report spells out the key steps you can take to help stop armed violence against women. [end text] [Inside front cover boxes] Violence against women Article 1 of the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women states that: “The term ‘violence against women’ means any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.”1 Gender-based violence According to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, gender-based violence against women is violence “directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately.”2 Such violence takes many forms, among them murder; stabbing; beating; rape; torture; sexual abuse; sexual harassment; threats and humiliation; forced prostitution and trafficking. -

Recommended Reading Original Source: JCSP Demonstration Library Project Updated Format: Ruby Crocker-Dunne, Student in Lucan Community College

Recommended Reading Original source: JCSP Demonstration Library Project Updated format: Ruby Crocker-Dunne, student in Lucan Community College Graphic Novels Author Title Publisher Comment Arakawa, Hiromu Fullmetal Alchemist Viz Media 27 book series Briggs, Raymond Fungus the Bogeyman Penguin Humorous Busiek, Kurt Avengers Assemble Marvel Popular title Colfer, Eoin Artemis Fowl Puffin Graphic version. This is easier to read Foreman, Micheal War Game Pavilion Factual, emotional WW1 story Hunt, Gerry Blood Upon the Rose O’Brien Press Engaging and popular way of presenting the 1916 Rising Isayama, Hajime Attack on Tital Kodansha Comics Manga series Kirkman, Robert The Walking Dead Image Hugely popular zombie apocalypse. Suitable for seniors Kishimoto, Masashi Naruto Viz Media Popular manga Mochizuki, Jun Pandora Hearts Yen Press Exciting manga story Muchamore, Robert The Recruit Hodder Graphic novel version of the original Spiegelman, Art The Complete Maus Penguin Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel-set in WW2 Various Bleach VIZ Media Popular manga series Various Ultimate X Men Marvel Slick, updated classic X- Men stories Venditti, Robert Percy Jackson and the Great adventure story Lightening Thief- th graphic novel Willingham, Bill Fables DC Comics Fairy tales in modern Mew York Young, Kim Twilight-The Graphic Atom A romance fantasy with Novel vampires Sports Author Title Publisher Comment Apps, Roy Dreams to Win Series Franklin Watts Bios of sporting heroes Croft, Andy Steven Gerrard (etc.) Barrington Stoke Sporting bios Freedman, Dan Jamie Johnstone Series Scholastic Soccer drama. Gripping Watt, Tom The Jags Series Rising Stars Football stories Historic Fiction Author Title Publisher Comment Boyne, John The Boy in the Transworld Poignant and dark.