Power and Globalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

Eighth Grade

Bibliography for Sheila Goeke 5/4/15 10:16 AM Bibliography Sorted by Author / Title. J F ALE Alexander, Kwame. The crossover. Fourteen-year-old twin basketball stars Josh and Jordan wrestle with highs and lows on and off the court as their father ignores his declining health. J 370.193 BEA Beals, Melba. Warriors don't cry : a searing memoir of the battle to integrate Little Rock's Central High. New York, N.Y. : Pocket Books, c1994. A memoir of the battle to integrate the Little Rock Central High School following the 1954 Supreme Court ruling. YA J F BEL Bell, Hilari. The last knight. 1st ed. New York, NY : Eos, c2007. In alternate chapters, eighteen-year-old Sir Michael Sevenson, an anachronistic knight errant, and seventeen-year-old Fisk, his street-wise squire, tell of their noble quest to bring Lady Ceciel to justice while trying to solve her husband's murder. J B JOBS Blumenthal, Karen. Steve Jobs : the man who thought different : a biography. 1st ed. New York : Feiwel & Friends, 2012. Chronicles the life and accomplishments of Apple mogul Steve Jobs, discussing his ideas, and describing how he has influenced life in the twenty-first century. J F BOD Bodeen, S. A. (Stephanie A.) , 1965-. The compound. 1st ed. New York : Feiwel and Friends, 2008. After his parents, two sisters, and he have spent six years in a vast underground compound built by his wealthy father to protect them from a nuclear holocaust, fifteen-year-old Eli, whose twin brother and grandmother were left behind, discovers that his father has perpetrated a monstrous hoax on them all. -

Contenidos 28 De Nov Al 04 De Diciembre De 2020 Boletín #379

CONTENIDOS 28 DE NOV AL 04 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2020 BOLETÍN #379 TEMA DE LA SEMANA: Iglesias, Feministas y activistas contra la violencia de género ................................ 4 1. Se insta a los líderes religiosos africanos a redoblar los esfuerzos contra la violencia de género ...................................... 4 2. Iglesias cubanas se mantienen en campaña por la No violencia hacia mujeres y niñas ..................................................... 5 3. Wikiclaves Violeta: activismo contra la violencia de género ................................................................................................. 5 4. La impunidad juega en contra en el combate a la violencia de género: ONU ...................................................................... 6 5. Crece la violencia de género: Sánchez Cordero .................................................................................................................. 6 6. Son ―insuficientes‖ las estrategias del Estado contra los feminicidios: CNDH ..................................................................... 7 7. Solicitud de día nacional de feminicidio divide las opiniones ............................................................................................... 7 8. ―La lucha feminista es una lucha por la sociedad‖ ................................................................................................................ 8 9. Reivindicaciones feministas: Gloria Muñoz Ramírez ........................................................................................................... -

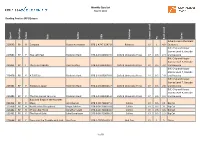

Qu Iz # Qu Iz Typ E Fictio N Title Auth O R ISBN Pu B Lish Er in Terest Level

Monthly Quiz List March 2016 Reading Practice (RP) Quizzes Quiz # Quiz Type Fiction Title Author ISBN Publisher Interest Level Pts Level Book Series Adventures in the Great 229693 RP N Camping Robyn Hardyman 978-1-4747-1547-8 Raintree LY 1 4.9 Outdoors Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 6, Decode 229583 RP F Two Left Feet Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830017-5 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.4 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229491 RP F The Time Capsule Paul Shipton 978-0-19-830028-1 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 3.2 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229478 RP F A Tall Tale Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830029-8 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.9 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 7, Decode 229481 RP F Holiday in Japan Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830026-7 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 2.8 and Develop Biff, Chip and Kipper Stories Level 9, Decode 229485 RP F The Fair-Haired Samurai Roderick Hunt 978-0-19-830041-0 Oxford University Press LY 0.5 3.3 and Develop Buzz and Bingo in the Monster 223452 RP F Maze Alan Durant 978-0-00-718617-4 Collins LY 0.5 3.1 Big Cat 223458 RP N Pacific Island Scrapbook Angie Belcher 978-0-00-718619-8 Collins LY 0.5 3.1 Big Cat 223442 RP N Africa's Big Three Jonathan Scott 978-0-00-718693-8 Collins LY 0.5 3.6 Big Cat 223461 RP F The Pot of Gold Julia Donaldson 978-0-00-718696-9 Collins LY 0.5 2.3 Big Cat 229648 RP F Daisy and the Trouble with Jack Kes Gray 978-1-78295-630-3 Red Fox LY 1 5 Daisy 1 of 9 The LEGO Movie: Calling All 229723 RP F Master Builders! David -

Capitalism Has Failed — What Next?

The Jus Semper Global Alliance In Pursuit of the People and Planet Paradigm Sustainable Human Development November 2020 ESSAYS ON TRUE DEMOCRACY AND CAPITALISM Capitalism Has Failed — What Next? John Bellamy Foster ess than two decades into the twenty-first century, it is evident that capitalism has L failed as a social system. The world is mired in economic stagnation, financialisation, and the most extreme inequality in human history, accompanied by mass unemployment and underemployment, precariousness, poverty, hunger, wasted output and lives, and what at this point can only be called a planetary ecological “death spiral.”1 The digital revolution, the greatest technological advance of our time, has rapidly mutated from a promise of free communication and liberated production into new means of surveillance, control, and displacement of the working population. The institutions of liberal democracy are at the point of collapse, while fascism, the rear guard of the capitalist system, is again on the march, along with patriarchy, racism, imperialism, and war. To say that capitalism is a failed system is not, of course, to suggest that its breakdown and disintegration is imminent.2 It does, however, mean that it has passed from being a historically necessary and creative system at its inception to being a historically unnecessary and destructive one in the present century. Today, more than ever, the world is faced with the epochal choice between “the revolutionary reconstitution of society at large and the common ruin of the contending classes.”3 1 ↩ George Monbiot, “The Earth Is in a Death Spiral. It will Take Radical Action to Save Us,” Guardian, November 14, 2018; Leonid Bershidsky, “Underemployment is the New Unemployment,” Bloomberg, September 26, 2018. -

Political Systems, Economics of Organization, and the Information Revolution (The Supply Side of Public Choice)

Political Systems, Economics of organization, and the Information Revolution (The Supply Side of Public Choice) Jean-Jacques Rosa Independent Institute Working Paper Number 27 April 2001 100 Swan Way, Oakland, CA 94621-1428 • 510-632-1366 • Fax: 510-568-6040 • Email: [email protected] • http://www.independent.org European Public Choice Society Meeting Paris, April 18-21, 2001 Political Systems, Economics of organization, and the Information Revolution (The Supply Side of Public Choice) Jean-Jacques Rosa Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Paris March 2001 Abstract: The political history of the twentieth century was characterised by great variability in the social and political systems in both time and space. The initial trend was one of general growth in the size of hierarchical organizations (giant firms, internal and external growth of States) then reversed in the last third of the century with the universal return to the market mechanism, break-up of conglomerates, re-specialisation and downsizing of large firms, the privatization of the public sector, the lightening of the tax burden in a number of countries, the atomization of several States (U.S.S.R., Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia) and the triumph of democracy. This paper extends the Coase analysis to the field of Public Choice. It shows how the cost of information is the basic determinant of the choice between markets and hierarchies. The relative scarcity of information thus explains the great cycle of political organization which lead decentralized and democratic societies at the end of the XIXth century to the totalitarian regimes of the first part of the XXth century, and then brought back most countries towards democratic regimes and market economies by the end of the “second XXth century”. -

Cosmopolitan Ethics and the Limits of Tolerance: Representing the Holocaust in Young Adult Literature

COSMOPOLITAN ETHICS AND THE LIMITS OF TOLERANCE: REPRESENTING THE HOLOCAUST IN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE Rachel L. Dean-Ruzicka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2011 Committee: Dr. Beth Greich-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Nancy W. Fordham Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Kimberly Coates Dr. Vivian Patraka © 2011 Rachel L. Dean-Ruzicka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Beth Greich-Polelle, Advisor This dissertation critically evaluates the concepts of tolerance and toleration and how these two ideas are often deployed as the appropriate response to any perceived difference in American culture. Using young adult literature about the Holocaust as a case study, this project illustrates how idealizing tolerance merely serves to maintain existing systems of power and privilege. Instead of using adolescent Holocaust literature to promote tolerance in educational institutions, I argue that a more effective goal is to encourage readers’ engagement and acceptance of difference. The dissertation examines approximately forty young adult novels and memoirs on the subject of the Holocaust. Through close readings of the texts, I illustrate how they succeed or fail at presenting characters that young adults can recognize as different from themselves in ways that will help to destabilize existing systems of power and privilege. I argue this sort of destabilization takes place through imaginative investment with a literary “Other” in order to develop a more cosmopolitan worldview. Using the theories of Judith Butler, Kwame Anthony Appiah, and Gerard Delanty I contended that engagement with and appreciation of difference is possible when reading young adult Holocaust literature. -

Inequality and the Top 10% in Europe Inequality and the Top 10% in Europe Inequality and the Top 10% in Europe Inequality and the Top 10% in Europe

? ? Inequality and the top 10% in Europe Inequality and the top 10% in Europe Inequality and the top 10% in Europe Inequality and the top 10% in Europe Published by: FEPS Foundation for European Progressive Studies Avenue des Arts, 46 1000 - Brussels T: +32 2 234 69 00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.feps-europe.eu/en/ Twitter @FEPS_Europe TASC 28 Merrion Square North Dublin 2 Ireland Tel: +353 1 616 9050 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.tasc.ie Twitter: @TASCblog © FEPS, TASC 2020 The present report does not represent the collective views of FEPS and TASC, but only of the respective authors. The responsibility of FEPS and TASC is limited to approving its publication as worthy of consideration of the global progressive movement. Disclaimer The present report does not represent the European Parliament’s views but only of the respective authors. 978-1-9993099-8-5 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents Methodology 18 Why care about the views of the top 10%? 19 Who are the top 10%? 21 Country comparison 24 Identifying the top 10% 28 How the top 10% has changed 36 Conclusion: so far away yet so close 43 Contextual and policy background 46 Who are the top 10% in the UK? 55 Perceptions of meritocracy and social mobility 56 The top 10% and belief in their own agency 58 Insecurity and the top 10% 63 Giving back: the top 10% 65 Public services and the top 10% 67 Politics and the top 10% 68 Inequality: what do the top 10% think about it? 71 Inequality: do the top 10% see a role for the state in addressing it? 76 The -

An Interpretive Case Study of a Leader's Effectual Power

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Dissertations Graduate School Spring 2018 Winning on and off Theour C t: An Interpretive Case Study of a Leader’s Effectual Power and Influence Eugene Smith Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss Part of the Educational Leadership Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Eugene, "Winning on and off Theour C t: An Interpretive Case Study of a Leader’s Effectual Power and Influence" (2018). Dissertations. Paper 142. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/diss/142 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WINNING ON AND OFF THE COURT: AN INTERPRETIVE CASE STUDY OF A LEADER’S EFFECTUAL POWER AND INFLUENCE A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Educational Leadership Doctoral Program Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Eugene Smith May 2018 “As a leader, I want to help others be better. I believe good leaders give others the opportunity to be better. Good leaders know their shortcomings and rely on others to contribute in the areas of the leader’s shortcomings.” Steve Moore, Head Basketball Coach at The College of Wooster, 2018 It is with great honor that I dedicate this dissertation to Steve Moore and his family. This research endeavor has been an incredible journey and immense learning experience. -

Sachbuch Literatur

AUFBAU A HERBST 2021 LITERATUR U SACHBUCH F B A U Unsere SPIEGEL- Bothor Mathias © Bestseller – wir danken Ihnen für Ihre Liebe Kolleginnen und Unsere Unterstützung! Kollegen im Handel, BESTSELLER bevor wir Ihnen unsere neuen Bücher vorstellen, »›Kindheit‹, ›Jugend‹ und möchte ich mich bedanken für ein Frühjahr, in dem ›Abhängigkeit‹ sind von atem- Sie trotz widriger Umstände – geschlossene Buch- handlungen, Lockdown und die Sorge darum, wie »Mit Diskriminierung beraubender Intensität und und vor allem wann eine Art von Normalität wieder und Unterdrückung Schönheit. Aus dem Staub ihres möglich sein wird – so viele unserer Bücher zu großen Lebens leuchtet dieses Werk: Erfolgen gemacht haben. beschäftigt sich die Jour- Die dänische Autorin Tove Ditlevsen, deren außeror- »Wer sich von Roig über nalistin und ARD-Tages- Tove Ditlevsen gilt es unbedingt dentliche Kopenhagen-Trilogie Sie mit uns zusammen die Wirklichkeit aufklären themen-Kommentatorin wiederzuentdecken.« entdeckt haben, schreibt im dritten Band »Abhängig- lässt, findet sich in Natalie Amiri, die zu den SPIEGEL ONLINE keit«: »Aber für mich ist das Leben nur ein Genuss, wenn ich schreiben kann.« So unverstellt und direkt, den künftigen Debatten »Osang kann einfach intimen Kennerinnen des so kompromisslos und zärtlich zugleich war selten ein besser zurecht.« fantastisch schreiben.« heutigen Iran gehört.« Blick auf das eigene Leben, und die Radikalität und DER SPIEGEL DIE ZEIT SÜDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG Intensität ihrer Schilderungen hat durch Sie und mit Ihnen ein großes Publikum begeistert. Die Macht der Literatur haben viele von uns in diesen Monaten erlebt, in denen Bücher zu Brücken wurden und uns befreit haben aus der Enge einer plötzlich begrenzten Welt. Wir brauchen Geschichten, wir leben in den eigenen Erzählungen ebenso wie in denen der anderen.