James Hutchison Stirling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 a Sermon Preached Before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 A sermon preached before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26. of November, 1645 / by Jer.Burroughus. - London : printed for R.Dawlman, 1646. -[6],48p.; 4to, dedn. - Final leaf lacking. Bound with r the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S. SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 438 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons assembled in Parliament at their publique thanksgiving September 7 1641 for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. - [8],64p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : Gauden, J. The love of truth and peace. London, 1641. 1S.SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons, September 7.1641, for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. - London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. -[8],54p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S.SERMONS BURT, Edward, fl.1755 D 695-6 Letters from a gentleman in the north of Scotland to his friend in London : containing the description of a capital town in that northern country, likewise an account of the Highlands. - A new edition, with notes. - London : Gale, Curtis & Fenner, 1815. - 2v. (xxviii, 273p. : xii,321p.); 22cm. - Inscribed "Caledonian Literary Society." 2.A GENTLEMAN in the north of Scotland. 3S.SCOTLAND - Description and travel I BURTON, Henry, 1578-1648 K 140 The bateing of the Popes bull] / [by HenRy Burton], - [London?], [ 164-?]. -

Chapter One James Mylne: Early Life and Education

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. 2013 THESIS Rational Piety and Social Reform in Glasgow: The Life, Philosophy and Political Economy of James Mylne (1757-1839) By Stephen Cowley The University of Edinburgh For the degree of PhD © Stephen Cowley 2013 SOME QUOTES FROM JAMES MYLNE’S LECTURES “I have no objection to common sense, as long as it does not hinder investigation.” Lectures on Intellectual Philosophy “Hope never deserts the children of sorrow.” Lectures on the Existence and Attributes of God “The great mine from which all wealth is drawn is the intellect of man.” Lectures on Political Economy Page 2 Page 3 INFORMATION FOR EXAMINERS In addition to the thesis itself, I submit (a) transcriptions of four sets of student notes of Mylne’s lectures on moral philosophy; (b) one set of notes on political economy; and (c) collation of lectures on intellectual philosophy (i.e. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews STORY AND FAITH: IN TilE BmLICAL NARRATIVE. Ulrich Simon. SPCK, 1975. 126 pp. £3.95/£1.95. In a series of short chapters Ulrich Simon, Professor of Christian Literature at King's College, London, examines the forms of narrative in Biblical and later literature, to see how these narratives work and what convictions they express. Gradually there emerges a picture of 'the Christian pattern' (summarised in chapter 21), which characteristically holds together polarities such as God and man, heaven and earth, perfection and degradation, death and resurrection, time and eternity, defeat and victory, love and hatred. The loss of the biblical narrative and the loss of this coherence go together; Simon illustrates modem attempts at 'the conquest of meaningless fragmentation' (p. 111), particularly Kafka. There are points of connection here with tradition criticism (the biblical work is reminiscent of von Rad), structuralism (the concern with binary oppositions), recent exhortations from James Barr to study the Bible as literature, and the history of culture as many Evangelicals have come to look at it through the spectacles of Schaeffer and Rookmaaker. Rookmaaker has pointed out that whereas art was once concerned both to portray real events and to suggest ultimate meaning, modem art has abandoned this vision. Simon suggests that the Bible seeks the same combination. He thus reminds us that biblical narrative must not be read as positivist history; it is a picture with a meaning, not a mere photograph. On the other hand, it is a picture of real events, and when the blurb speaks of such narrative as an exposure of the human condition rather than a description of events, it falls into just the kind of false antithesis that Simon describes the biblical narrative as overcoming. -

James Huchison Stirling

Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism Working Paper Series Number 3 Bibliographies of Richard Lewis Nettleship (1846-1892), James Hutchison Stirling (1820-1909) & William Wallace (1844-1897) (2018 version) Compiled by Professor Colin Tyler Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism University of Hull Every Working Paper is peer reviewed prior to acceptance. Authors & compilers retain copyright in their own Working Papers. For further information on the Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism, and its activities, visit our website: http://www.hull.ac.uk/pas/ Or, contact the Centre Directors Colin Tyler: [email protected] James Connelly: [email protected] Centre for Idealism and the New Liberalism School of Lae and Politics University of Hull, Cottingham Road Hull, HU6 7RX, United Kingdom Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Richard Lewis Nettleship (1846-1892) I. Writings 4 II. Reviews and obituaries 5 III. Other discussions 5 James Hutchison Stirling (1820-1909) I. Writings 6 II. Reviews and obituaries 10 III. Other discussions 12 William Wallace (1844-1897) I. Writings 16 II. Reviews and obituaries 18 III. Other discussions 20 Notes on Henry Nettleship (1839-93) 21 2 Acknowledgments for the 2018 version Once again, I am pleased to thank those scholars who sent in references, and hope they will not mind my not mentioning them individually. Future references will continue to be received with thanks. Professor Colin Tyler University of Hull December 2017 Acknowledgments for the original, 2004 version The work on these bibliographies was supported by a Resource Enhancement Award (B/RE/AN3141/APN17357) from the Arts and Humanities Research Board. -

Philip Flynn Scottish Philosophers, Scotch Reviewers, and the Science of Mind in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries

Philip Flynn Scottish Philosophers, Scotch Reviewers, and the Science of Mind In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the study ofthe mind was in a transitional phase-no longer an official handmaid to theol ogy and not yet an official aspect of neurobiology. In Scotland several generations of philosophers found themselves inspired or perplexed by the hope expressed at the conclusion of Sir Isaac Newton's Opticks ( 1704), the hope that inductive reasoning might be applied in moral as well as natural philosophy .1 These Scottish thinkers did not have a sophisticated knowledge of the electrical and chemical aspects of man's cognitive life. That was a disadvantage that they shared with their age. But, in their desire to learn from Francis Bacon and to emulate Newton, they attempted to be scientific-to comprehend a wide range of phenomena under a few principles or laws, all the while aware of the danger of confusing speculation with the scientific state ment of observed phenomena. In exploring the proper role of hypothesis, the limits of induction, and the nature of causal relation ships, they were not only studying the mind (or phenomena called "mental") but also studying the study of the mind, clarifying the methods and assumptions of an introspective philosophy and of the physical sciences. This essay is concerned with one stage of that adventure, a public debate in the early nineteenth century that involved Scottish academic philosophers, Scottish periodical review ers, and reviewers who became academics. At the close of the eighteenth century, Dugald Stewart was the most influential philosopher active in Scotland, a teacher whose "gentle and persuasive eloquence" has been described by Henry Cockburn, James Mackintosh, and others among his students. -

German Political Thought and the Discourse of Platonism

German Political Thought and the Discourse of Platonism “Tis book is a genuine tour de force. Paul Bishop reads the tradition of German political thought through the prism of the allegory of the cave in Plato’s Republic. His aim is not merely to re-contextualise and re-interpret, but to reveal the continued relevance of the history of ideas to our own time. In a series of penetrating interpretations ranging from Plato and Aristotle via Rousseau, Kant, Hegel, Marx, and Nietzsche to Heidegger, Adorno, and Habermas, he addresses the central challenges of modernity—such as the rela- tion between the individual and society, the promises and pitfalls of economic development, and the role of the state. Tis is an original and engaging way into the intricacies of German thought. Supremely erudite yet invariably acces- sible, the book works on two levels: undergraduate students will be able to use it as a general introduction, while scholars will beneft from its interpretative subtleties and historical insights. German Political Tought and the Discourse of Platonism is one of the most fascinating philosophical studies I have read in a long time.” —Henk de Berg is Professor of German at the University of Shefeld, UK, and co-editor of Modern German Tought from Kant to Habermas (2012) “Paul Bishop ofers a stunning revision of political thinking via Plato and his continued presence in German philosophy. Plato’s Cave is the famous allegory that depicts humans as doomed to remain prisoners deluded by shadows on the cave wall when their only hope of freedom is to focus on the mystical fre itself. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. ASPECTS OF WILLIAM WHEWELL'S PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE by Dennis R. Murray. A thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Arts The Department of Philosophy (School of General Studies) The Australian National University June 1974. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Richard Campbell of the School of Philosophy (General Studies) in the Australian National University, and to the staff of the School of the History and Philosophy of Science in the University of New South Wales, for their advice and encouragement in the preparation of this study. "Between the idea And the reality Between the motion And the act Falls the shadow." from "The Hollow Men" by T.S. Eliot CONTENTS Abbreviations i Preface ii Chapter One THE GENERAL CHARACTER OF WHEWELL'S THOUGHT 7 1. Whewell's Life and Writings 7 2. General Outline of Whewell's Philosophical Views 16 Chapter Two NECESSARY TRUTH 23 Chapter Three INDUCTION 43 1. The Clarification of the Elements of Knowledge by Analysis 45 2. The Colligation of Facts by Means of a Conception 48 i) Colligation as the type of Induction 49 ii) Mill's Criticism 52 3. Verification of the Colligation 61 i) Three Criteria 61 ii) The11Logic of Induction" 65 Chapter Four "THE FUNDAMENTAL ANTITHESIS OF PHILOSOPHY" 75 1. -

Oxford Liberalism and the Return of Patriarchy

CHAPTER ONE Oxford Liberalism and the Return of Patriarchy IN 1938, GILBERT MURRAY ARGUED IN Liberality and Civilization that liberalism was “not a doctrine; it is a spirit or attitude of mind . an effort to get rid of prejudice so as to see the truth, to get rid of selfish passions so as to do the right.”1 Murray had suggested something similar fifty years earlier, while a young fellow at Oxford in 1888. In an unpub- lished speech to the Russell Club, he suggested that the foundational logic of what he described as the “new liberalism” was an emerging consensus that something other than self-interest—something other than what Mur- ray then called “that negative way the old Liberals got their enthusi- asm”—must motivate liberal social theory.2 Murray’s consistency on this matter demonstrates the profundity of his belief that liberalism ought to be understood as an essentially spiritual and deeply selfless approach to politics and to life, an antidote, in fact, to almost all the problems of modernity. In the final analysis, it was this faith in liberalism as essentially transformative (a faith shared by Zimmern) that would map out the con- tours of Murray’s political theory and shape his approach to internation- alism. It would also lead to future charges of utopianism. And yet Murray’s particular formulation of liberalism was hardly par- ticular. It was, rather, conditioned by a reformist tradition within British liberalism, associated most directly with T. H. Green and his students and colleagues at Oxford, a tradition that arose out of what these earlier thinkers perceived as a deep crisis within liberal theory. -

A Bibliography of Scottish Common Sense Philosophy

SCOTTISH COMMON SENSE PHILOSOPHY Sources and Origins Volume 5 Edited and Introduced by James Fieser University of Tennessee at Martin THOEMMES Scottish Common Sense Philosophy: Sources and Origins A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF SCOTTISH Edited and Introduced by James Fieser University of Tennessee at Martin, USA COMMON SENSE PHILOSOPHY Volume 1 James Oswald, An Appeal to Common Sense in Behalf of Religion (1766–1772) Volume 2 James Beattie, An Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth (1770) Volumes 3 and 4 Early Responses to Reid, Oswald, Beattie and Stewart Volume 5 A Bibliography of Scottish Common Sense Philosophy Edited with a Preface by James Fieser University of Tennessee at Martin THOEMMES PRESS First published by Thoemmes Press, 2000 Thoemmes Press 11 Great George Street Bristol BS1 5RR, England Thoemmes Press US Office CONTENTS 22883 Quicksilver Drive Sterling, Virginia 20166, USA Editor’s Preface vii http://www.thoemmes.com 1. John Abercrombie (1780–1844) 1 2. James Beattie (1735–1803) 10 Scottish Common Sense Philosophy: Sources and Origins 5 Volumes : ISBN 1 85506 825 7 3. Thomas Brown (1778–1820) 34 4. George Campbell (1719–1796) 41 © James Fieser, 2000 5. James Dunbar (1742–1798) 56 6. David Fordyce (1711–1751) 58 7. Alexander Gerard (1728–1795) 62 8. William Hamilton (1788–1856) 66 9. Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696–1782) 78 10. James Oswald (1703–1793) 97 11. Thomas Reid (1710–1796) 102 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data 12. Dugald Stewart (1753–1828) 123 A CIP record of this title is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any way or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright holder. -

James Hutchison Stirling : His Life and Work

CHAPTER XVIII 1886-1890 Financial worries Law-suit The Gifford Lectures Stirling s Religious Position As far as literary or philosophical work was concerned, the year 1886 was almost a blank in Stirling s life. During the year, nothing whatever appeared from his pen save a short letter in the the " Italian Athenceum on Hegelians," suggested by the publication of an important work on political philosophy by Professor Levi La Dottrina dello Stato. No doubt, he would have given more than a mere passing mention to a book of such importance but that, at the time it appeared, he was undergoing all the worry and anxiety connected with a law-suit, loss of a which involved the (if unsuccessful) large sum of money. The limits of space preclude the possibility of giving here even an outline of what was at the time somewhat of a cause celebre, the decision in which came as a surprise to all impartial outsiders, and seemed to make startlingly apparent the distinction between equity and legality. Stirling s friends and admirers showed their sympathy with him in a substantial form a to the ; subscription defray legal expenses of the case was set on foot by a group of friends, among the more active of whom were Professors Laurie and Masson, Mr. Archibald Constable, and the Rev. James Wood a man of literary tastes, and mild, gentle character, for whom Stirling had a warm friendship. From all over Great Britain, and from America, contributions were received. One of the largest came from 308 HIS LIFE AND WORK 309 India, where Stirling had an earnest disciple in Ras bihari Mukharji, a high-caste Hindu, and author of a translation into excellent English of Kenan s Dialogues et Fragments Philosophiqiies. -

Unit I David Hume

Unit I David Hume ―Hume is our Politics, Hume is our Trade, Hume is our Philosophy, Hume is our Religion.‖ This statement by nineteenth century philosopher James Hutchison Stirling reflects the unique position in intellectual thought held by Scottish philosopher David Hume. Part of Hume‘s fame and importance owes to his boldly skeptical approach to a range of philosophical subjects. In epistemology, he questioned common notions of personal identity, and argued that there is no permanent ―self‖ that continues over time. He dismissed standard accounts of causality and argued that our conceptions of cause-effect relations are grounded in habits of thinking, rather than in the perception of causal forces in the external world itself. He defended the skeptical position that human reason is inherently contradictory, and it is only through naturally-instilled beliefs that we can navigate our way through common life. In the philosophy of religion, he argued that it is unreasonable to believe testimonies of alleged miraculous events, and he hints, accordingly, that we should reject religions that are founded on miracle testimonies. Against the common belief of the time that God‘s existence could be proven through a design or causal argument, Hume offered compelling criticisms of standard theistic proofs. He also advanced theories on the origin of popular religious beliefs, grounding such notions in human psychology rather than in rational argument or divine revelation. The larger aim of his critique was to disentangle philosophy from religion and thus allow philosophy to pursue its own ends without rational over-extension or psychological corruption. In moral theory, against the common view that God plays an important role in the creation and reinforcement of moral values, he offered one of the first purely secular moral theories, which grounded morality in the pleasing and useful consequences that result from our actions. -

1 Introduction

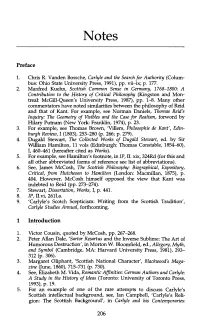

Notes Preface 1. Chris R. Vanden Bossche, Carlyle and the Search for Authority (Colum bus: Ohio State University Press, 1991), pp. vii-ix; p. 177. 2. Manfred Kuehn, Scottish Common Sense in Germany, 1768-1800: A Contribution to the History of Critical Philosophy (Kingston and Mon treal: MeGill-Queen's University Press, 1987), pp. 1-8. Many other commentators have noted similarities between the philosophy of Reid and that of Kant. For example, see Norman Daniels, Thomas Reid's Inquiry: The Geometry of Visibles and the Case for Realism, forword by Hilary Putnam (New York: Franklin, 1974), p. 23. 3. For example, see Thomas Brown, 'Villers, Philosophie de Kant', Edin burgh Review, I (1803), 253-280 (p. 266; p. 279). 4. Dugald Stewart, The Collected Works of Dugald Stewart, ed. by Sir William Hamilton, 11 vols (Edinburgh: Thomas Constable, 1854-60), I, 460-461 (hereafter cited as Works). 5. For example, see Hamilton's footnote, in IP, II. xix, 324Rd (for this and all other abbreviated forms of reference see list of abbreviations). 6. See, James McCosh, The Scottish Philosophy: Biographical, Expository, Critical, from Hutcheson to Hamilton (London: Macmillan, 1875), p. 404. However, McCosh himself opposed the view that Kant was indebted to Reid (pp. 273-274). 7. Stewart, Dissertation, Works, I, p. 441. 8. IP, Il.vi, 261La. 9. 'Carlyle's Scotch Scepticism: Writing from the Scottish Tradition', Carlyle Studies Annual, forthcoming. 1 Introduction 1. Victor Cousin, quoted by McCosh, pp. 267-268. 2. Peter Allan Dale, 'Sartor Resartus and the Inverse Sublime: The Art of Humorous Destruction', in Morton W.