A Competitive Binding Model Predicts Nonlinear Responses of Olfactory Receptors to Complex Mixtures Vijay Singha,B, Nicolle R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Variation Across the Human Olfactory Receptor Repertoire Alters Odor Perception

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/212431; this version posted November 1, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Genetic variation across the human olfactory receptor repertoire alters odor perception Casey Trimmer1,*, Andreas Keller2, Nicolle R. Murphy1, Lindsey L. Snyder1, Jason R. Willer3, Maira Nagai4,5, Nicholas Katsanis3, Leslie B. Vosshall2,6,7, Hiroaki Matsunami4,8, and Joel D. Mainland1,9 1Monell Chemical Senses Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA 2Laboratory of Neurogenetics and Behavior, The Rockefeller University, New York, New York, USA 3Center for Human Disease Modeling, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 4Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 5Department of Biochemistry, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil 6Howard Hughes Medical Institute, New York, New York, USA 7Kavli Neural Systems Institute, New York, New York, USA 8Department of Neurobiology and Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA 9Department of Neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA *[email protected] ABSTRACT The human olfactory receptor repertoire is characterized by an abundance of genetic variation that affects receptor response, but the perceptual effects of this variation are unclear. To address this issue, we sequenced the OR repertoire in 332 individuals and examined the relationship between genetic variation and 276 olfactory phenotypes, including the perceived intensity and pleasantness of 68 odorants at two concentrations, detection thresholds of three odorants, and general olfactory acuity. -

OR2W1 (Human) Recombinant Protein

OR2W1 (Human) Recombinant Entrez GeneID: 26692 Protein Gene Symbol: OR2W1 Catalog Number: H00026692-G01 Gene Alias: MGC119162, MGC119163, MGC119165, hs6M1-15 Regulation Status: For research use only (RUO) Gene Summary: Olfactory receptors interact with Product Description: Human OR2W1 full-length ORF odorant molecules in the nose, to initiate a neuronal (NP_112165.1) recombinant protein without tag. response that triggers the perception of a smell. The olfactory receptor proteins are members of a large family Sequence: of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) arising from MDQSNYSSLHGFILLGFSNHPKMEMILSGVVAIFYLITL single coding-exon genes. Olfactory receptors share a VGNTAIILASLLDSQLHTPMYFFLRNLSFLDLCFTTSIIP 7-transmembrane domain structure with many QMLVNLWGPDKTISYVGCIIQLYVYMWLGSVECLLLAV neurotransmitter and hormone receptors and are MSYDRFTAICKPLHYFVVMNPHLCLKMIIMIWSISLANS responsible for the recognition and G protein-mediated VVLCTLTLNLPTCGNNILDHFLCELPALVKIACVDTTTV transduction of odorant signals. The olfactory receptor EMSVFALGIIIVLTPLILILISYGYIAKAVLRTKSKASQRKA gene family is the largest in the genome. The MNTCGSHLTVVSMFYGTIIYMYLQPGNRASKDQGKFL nomenclature assigned to the olfactory receptor genes TLFYTVITPSLNPLIYTLRNKDMKDALKKLMRFHHKSTK and proteins for this organism is independent of other IKRNCKS organisms. [provided by RefSeq] Host: Wheat Germ (in vitro) Theoretical MW (kDa): 36.1 Applications: AP (See our web site product page for detailed applications information) Protocols: See our web site at http://www.abnova.com/support/protocols.asp or product page for detailed protocols Form: Liquid Preparation Method: in vitro wheat germ expression system with proprietary liposome technology Purification: None Recommend Usage: Heating may cause protein aggregation. Please do not heat this product before electrophoresis. Storage Buffer: 25 mM Tris-HCl of pH8.0 containing 2% glycerol. Storage Instruction: Store at -80°C. Aliquot to avoid repeated freezing and thawing. Page 1/1 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

Kras, Braf, Erbb2, Tp53

Supplementary Table 1. SBT-EOC cases used for molecular analyses Fresh Frozen Tissue FFPE Tissue Tumour HRM Case ID PCR-Seq HRM component Oncomap (KRAS, BRAF, CNV GE CNV IHC (NRAS) (TP53 Only) ERBB2, TP53) Paired Cases 15043 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ √ 65662 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ 65661 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ √ 9128 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ 2044 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ 3960 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ 5899 SBT & INV √ √ √ √ √ 65663 SBT & INV √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ 65666 SBT √ Inv √ √ √ √ √ 65664 SBT √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ √ √ 15060 SBT √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ √ √ 65665 SBT √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ √ √ 65668 SBT √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ √ 65667 SBT √ √ √ Inv √ √ √ √ 15018 SBT √ Inv √ √ √ √ 15071 SBT √ Inv √ √ √ √ 65670 SBT √ Inv √ √ √ 8982 SBT √ Unpaired Cases 15046 Inv √ √ √ 15014 Inv √ √ √ 65671 Inv √ √ √ 65672 SBT √ √ √ 65673 Inv √ √ √ 65674 Inv √ √ √ 65675 Inv √ √ √ 65676 Inv √ √ √ 65677 Inv √ √ √ 65678 Inv √ √ √ 65679 Inv √ √ √ Fresh Frozen Tissue FFPE Tissue Tumour HRM Case ID PCR-Seq HRM component Oncomap (KRAS, BRAF, CNV GE CNV IHC (NRAS) (TP53 Only) ERBB2, TP53) 65680 Inv √ √ √ 5349 Inv √ √ √ 7957 Inv √ √ √ 8395 Inv √ √ √ 8390 Inv √ √ 2110 Inv √ √ 6328 Inv √ √ 9125 Inv √ √ 9221 Inv √ √ 10701 Inv √ √ 1072 Inv √ √ 11266 Inv √ √ 11368 Inv √ √ √ 12237 Inv √ √ 2064 Inv √ √ 3539 Inv √ √ 2189 Inv √ √ √ 5711 Inv √ √ 6251 Inv √ √ 6582 Inv √ √ 7200 SBT √ √ √ 8633 Inv √ √ √ 9579 Inv √ √ 10740 Inv √ √ 11766 Inv √ √ 3958 Inv √ √ 4723 Inv √ √ 6244 Inv √ √ √ 7716 Inv √ √ SBT-EOC, serous carcinoma with adjacent borderline regions; SBT, serous borderline component of SBT- EOC; Inv, invasive component of SBT-EOC; -

Olfactory Receptors in Non-Chemosensory Organs: the Nervous System in Health and Disease

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sissa Digital Library REVIEW published: 05 July 2016 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00163 Olfactory Receptors in Non-Chemosensory Organs: The Nervous System in Health and Disease Isidro Ferrer 1,2,3*, Paula Garcia-Esparcia 1,2,3, Margarita Carmona 1,2,3, Eva Carro 2,4, Eleonora Aronica 5, Gabor G. Kovacs 6, Alice Grison 7 and Stefano Gustincich 7 1 Institute of Neuropathology, Bellvitge University Hospital, Hospitalet de Llobregat, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2 Center for Biomedical Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases (CIBERNED), Madrid, Spain, 3 Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBELL), Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain, 4 Neuroscience Group, Research Institute Hospital, Madrid, Spain, 5 Department of Neuropathology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 6 Institute of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria, 7 Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA), Area of Neuroscience, Trieste, Italy Olfactory receptors (ORs) and down-stream functional signaling molecules adenylyl cyclase 3 (AC3), olfactory G protein a subunit (Gaolf), OR transporters receptor transporter proteins 1 and 2 (RTP1 and RTP2), receptor expression enhancing protein 1 (REEP1), and UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) are expressed in neurons of the human and murine central nervous system (CNS). In vitro studies have shown that these receptors react to external stimuli and therefore are equipped to be functional. However, ORs are not directly related to the detection of odors. Several molecules delivered from the blood, cerebrospinal fluid, neighboring local neurons and glial cells, distant cells through the extracellular space, and the cells’ own self-regulating internal homeostasis Edited by: Filippo Tempia, can be postulated as possible ligands. -

Predicting Human Olfactory Perception from Activities of Odorant Receptors

iScience ll OPEN ACCESS Article Predicting Human Olfactory Perception from Activities of Odorant Receptors Joel Kowalewski, Anandasankar Ray [email protected] odor perception HIGHLIGHTS Machine learning predicted activity of 34 human ORs for ~0.5 million chemicals chemical structure Activities of human ORs predicts OR activity could predict odor character using machine learning Few OR activities were needed to optimize r predictions of each odor e t c percept a AI r a odorant activates mul- h Behavior predictions in c Drosophila also need few r tiple ORs o olfactory receptor d o activities ts ic ed pr ity tiv ac OR Kowalewski & Ray, iScience 23, 101361 August 21, 2020 ª 2020 The Author(s). https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.isci.2020.101361 iScience ll OPEN ACCESS Article Predicting Human Olfactory Perception from Activities of Odorant Receptors Joel Kowalewski1 and Anandasankar Ray1,2,3,* SUMMARY Odor perception in humans is initiated by activation of odorant receptors (ORs) in the nose. However, the ORs linked to specific olfactory percepts are unknown, unlike in vision or taste where receptors are linked to perception of different colors and tastes. The large family of ORs (~400) and multiple receptors activated by an odorant present serious challenges. Here, we first use machine learning to screen ~0.5 million compounds for new ligands and identify enriched structural motifs for ligands of 34 human ORs. We next demonstrate that the activity of ORs successfully predicts many of the 146 different perceptual qualities of chem- icals. Although chemical features have been used to model odor percepts, we show that biologically relevant OR activity is often superior. -

Sean Raspet – Molecules

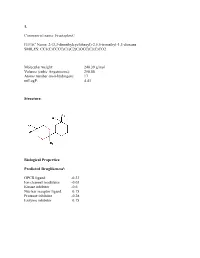

1. Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Molecular weight: 240.39 g/mol Volume (cubic Angstroems): 258.88 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.43 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikenessi: GPCR ligand -0.23 Ion channel modulator -0.03 Kinase inhibitor -0.6 Nuclear receptor ligand 0.15 Protease inhibitor -0.28 Enzyme inhibitor 0.15 Commercial name: Fructaplex© IUPAC Name: 2-(3,3-dimethylcyclohexyl)-2,5,5-trimethyl-1,3-dioxane SMILES: CC1(C)CCCC(C1)C2(C)OCC(C)(C)CO2 Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activityii: OR2L13 83.715% OR1G1 82.761% OR10J5 80.569% OR2W1 78.180% OR7A2 77.696% 2. Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Molecular weight: 239.36 Volume (cubic Angstroems): 252.83 Atoms number (non-hydrogen): 17 miLogP: 4.33 Structure: Biological Properties: Predicted Druglikeness: GPCR ligand -0.6 Ion channel modulator -0.41 Kinase inhibitor -0.93 Nuclear receptor ligand -0.17 Protease inhibitor -0.39 Enzyme inhibitor 0.01 Commercial name: Sylvoxime© IUPAC Name: N-[4-(1-ethoxyethenyl)-3,3,5,5tetramethylcyclohexylidene]hydroxylamine SMILES: CCOC(=C)C1C(C)(C)CC(CC1(C)C)=NO Predicted Olfactory Receptor Activity: OR52D1 71.900% OR1G1 70.394% 0R52I2 70.392% OR52I1 70.390% OR2Y1 70.378% 3. Commercial name: Hyperflor© IUPAC Name: 2-benzyl-1,3-dioxan-5-one SMILES: O=C1COC(CC2=CC=CC=C2)OC1 Molecular weight: 192.21 g/mol Volume -

Functional Variability in the Human Odorant Receptor Repertoire

ART ic LE s The missense of smell: functional variability in the human odorant receptor repertoire Joel D Mainland1–3, Andreas Keller4, Yun R Li2,6, Ting Zhou2, Casey Trimmer1, Lindsey L Snyder1, Andrew H Moberly1,3, Kaylin A Adipietro2, Wen Ling L Liu2, Hanyi Zhuang2,6, Senmiao Zhan2, Somin S Lee2,6, Abigail Lin2 & Hiroaki Matsunami2,5 Humans have ~400 intact odorant receptors, but each individual has a unique set of genetic variations that lead to variation in olfactory perception. We used a heterologous assay to determine how often genetic polymorphisms in odorant receptors alter receptor function. We identified agonists for 18 odorant receptors and found that 63% of the odorant receptors we examined had polymorphisms that altered in vitro function. On average, two individuals have functional differences at over 30% of their odorant receptor alleles. To show that these in vitro results are relevant to olfactory perception, we verified that variations in OR10G4 genotype explain over 15% of the observed variation in perceived intensity and over 10% of the observed variation in perceived valence for the high-affinity in vitro agonist guaiacol but do not explain phenotype variation for the lower-affinity agonists vanillin and ethyl vanillin. The human genome contains ~800 odorant receptor genes that have RESULTS been shown to exhibit high genetic variability1–3. In addition, humans High-throughput screening of human odorant receptors exhibit considerable variation in the perception of odorants4,5, and To identify agonists for a variety of odorant receptors, we cloned a variation in an odorant receptor predicts perception in four cases: library of 511 human odorant receptor genes for a high-throughput loss of function in OR11H7P, OR2J3, OR5A1 and OR7D4 leads to heterologous screen. -

Screening of Ancestral Polymorphisms for Immune Response Genes

Screening of Ancestral Polymorphisms for Immune Response Genes vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Sven M. Dillenburger aus Berlin von der Fakultät III - Prozesswissenschaften der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften - Dr.-Ing. - genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsauschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. R. Lauster Berichter: Prof. Dipl-Ing. Dr. U. Stahl Berichter: Dr. T. D. Taylor Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 20. Dezember 2007 Berlin 2008 D 83 1 Abbreviations and Glossary Allele Allele is used for two or more alternative forms of a gene resulting in different gene products and thus different phenotypes. An organism is homozygous for a gene if the alleles are identical, and heterozygous if they are different. Adenine (A) A purine base (nitrogenous base) and constituent of nucleotides and as such one member of the base pair A-T (adenine-thymine) in DNA and A-U (adenine-uracil) in RNA. Annotation The process of attaching biological information to DNA sequences. It consists of two procedures: 1. identifying elements in a genome, and 2. attaching biological information (ORFs and their localization, gene structure, coding regions, location of regulatory motifs, etc) to these elements. Automatic annotation tools (e.g. Ensembl) try to perform every step of this by computer analysis, as opposed to manual annotation, which involves human expertise. Alignment The process of lining up two or more sequences to achieve maximal levels of identity (and conservation, in the case of amino acid sequences) for the purpose of assessing the degree of similarity and the presence of homology. 2 BAC clone Bacterial artificial chromosome vector which carries a genomic DNA insert. -

Clinical, Molecular, and Immune Analysis of Dabrafenib-Trametinib

Supplementary Online Content Chen G, McQuade JL, Panka DJ, et al. Clinical, molecular and immune analysis of dabrafenib-trametinib combination treatment for metastatic melanoma that progressed during BRAF inhibitor monotherapy: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. Published online April 28, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0509. eMethods. eReferences. eTable 1. Clinical efficacy eTable 2. Adverse events eTable 3. Correlation of baseline patient characteristics with treatment outcomes eTable 4. Patient responses and baseline IHC results eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival eFigure 2. Correlation between IHC and RNAseq results eFigure 3. pPRAS40 expression and PFS eFigure 4. Baseline and treatment-induced changes in immune infiltrates eFigure 5. PD-L1 expression eTable 5. Nonsynonymous mutations detected by WES in baseline tumors This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/30/2021 eMethods Whole exome sequencing Whole exome capture libraries for both tumor and normal samples were constructed using 100ng genomic DNA input and following the protocol as described by Fisher et al.,3 with the following adapter modification: Illumina paired end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8 base index sequences embedded within the adapter. In-solution hybrid selection was performed using the Illumina Rapid Capture Exome enrichment kit with 38Mb target territory (29Mb baited). The targeted region includes 98.3% of the intervals in the Refseq exome database. Dual-indexed libraries were pooled into groups of up to 96 samples prior to hybridization. -

A Study of the Differential Expression Profiles of Keshan Disease Lncrna/Mrna Genes Based on RNA-Seq

421 Original Article A study of the differential expression profiles of Keshan disease lncRNA/mRNA genes based on RNA-seq Guangyong Huang1, Jingwen Liu2, Yuehai Wang1, Youzhang Xiang3 1Department of Cardiology, Liaocheng People’s Hospital of Shandong University, Liaocheng, China; 2School of Nursing, Liaocheng Vocational & Technical College, Liaocheng, China; 3Shandong Institute for Endemic Disease Control, Jinan, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: G Huang, Y Xiang; (II) Administrative support: G Huang, Y Wang; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: G Huang, J Liu, Y Xiang; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: G Huang, J Liu; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: J Liu, Y Wang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Guangyong Huang, MD, PhD. Department of Cardiology, Liaocheng People’s Hospital of Shandong University, No. 67 of Dongchang Street, Liaocheng 252000, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: This study aims to analyze the differential expression profiles of lncRNA in Keshan disease (KSD) and to explore the molecular mechanism of the disease occurrence and development. Methods: RNA-seq technology was used to construct the lncRNA/mRNA expression library of a KSD group (n=10) and a control group (n=10), and then Cuffdiff software was used to obtain the gene lncRNA/ mRNA FPKM value as the expression profile of lncRNA/mRNA. The fold changes between the two sets of samples were calculated to obtain differential lncRNA/mRNA expression profiles, and a bioinformatics analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed. Results: A total of 89,905 lncRNAs and 20,315 mRNAs were detected. -

The Hypothalamus As a Hub for SARS-Cov-2 Brain Infection and Pathogenesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The hypothalamus as a hub for SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and pathogenesis Sreekala Nampoothiri1,2#, Florent Sauve1,2#, Gaëtan Ternier1,2ƒ, Daniela Fernandois1,2 ƒ, Caio Coelho1,2, Monica ImBernon1,2, Eleonora Deligia1,2, Romain PerBet1, Vincent Florent1,2,3, Marc Baroncini1,2, Florence Pasquier1,4, François Trottein5, Claude-Alain Maurage1,2, Virginie Mattot1,2‡, Paolo GiacoBini1,2‡, S. Rasika1,2‡*, Vincent Prevot1,2‡* 1 Univ. Lille, Inserm, CHU Lille, Lille Neuroscience & Cognition, DistAlz, UMR-S 1172, Lille, France 2 LaBoratorY of Development and PlasticitY of the Neuroendocrine Brain, FHU 1000 daYs for health, EGID, School of Medicine, Lille, France 3 Nutrition, Arras General Hospital, Arras, France 4 Centre mémoire ressources et recherche, CHU Lille, LiCEND, Lille, France 5 Univ. Lille, CNRS, INSERM, CHU Lille, Institut Pasteur de Lille, U1019 - UMR 8204 - CIIL - Center for Infection and ImmunitY of Lille (CIIL), Lille, France. # and ƒ These authors contriButed equallY to this work. ‡ These authors directed this work *Correspondence to: [email protected] and [email protected] Short title: Covid-19: the hypothalamic hypothesis 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.08.139329; this version posted June 19, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity.