Celebrity Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tῆς Πάσης Ναυτιλίης Φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea*

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 23 | 2010 Varia Tῆς πάσης ναυτιλίης φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea Denise Demetriou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/1567 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.1567 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2010 Number of pages: 67-89 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Denise Demetriou, « Tῆς πάσης ναυτιλίης φύλαξ: Aphrodite and the Sea », Kernos [Online], 23 | 2010, Online since 10 October 2013, connection on 30 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ kernos/1567 ; DOI : 10.4000/kernos.1567 Kernos Kernos 23 (2010), p. .7-A9. T=> ?@AB> CDEFGHIB> JKHDL5 Aphrodite a d the Seau AbstractS This paper offers a co ection of genera y neg ected He enistic epigrams and some iterary and epigraphic e2idence that attest to the worship of Aphrodite as a patron deity of na2igation. The goddess8 temp es were often coasta not 1ecause they were p aces where _sacred prostitution” was practiced, 1ut rather 1ecause of Aphrodite8s association with the sea and her ro e as a patron of seafaring. The protection she offered was to anyone who sai ed, inc uding the na2y and traders, and is attested throughout the Mediterranean, from the Archaic to the He enistic periods. Further, the teLts eLamined here re2ea a metaphorica ink 1etween Aphrodite8s ro e as patron of na2igation and her ro e as a goddess of seLua ity. Résumé S Cet artic e pr sente une s rie d8 pigrammes he nistiques g n ra ement peu tudi es et que ques t moignages itt raires et pigraphiques attestant e cu te d8Aphrodite en tant que protectrice de a na2igation. -

7227134.Pdf (14.36

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s|". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Seven Wonders Time: 30 Minutes Level: Beginner

Lesson Five: Seven Wonders Time: 30 minutes Level: Beginner Intro The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were architectural feats recorded by ancient historians, writers and scholars in the western world - the list is limited geographically to the mediterranean, the centre of ancient western civilization. The only remaining wonder in the present day is the Great Pyramid of Giza, which is also the oldest. The rest have all been destroyed by weather, war or nature. Today we’re going to learn a little bit about each one: The Great Pyramid of Giza The pyramids are, in many ways, the most famous ancient wonder of the world. Whether that’s attributed to their mystery, incredible feat of construction, or their sole survival (out of all of the ancient wonders) into the modern era, all marvel at their magnificence. The Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed around 2589-2566 B.C. during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu. It stood about 147 meters tall and its base was approximately 230 meters in length. The second pyramid was created for Khufu’s son, Pharaoh Khafre, in 2558-2532 B.C. Within the pyramid’s complex at Giza was the largest statue in the world at that time, known as the Great Sphinx (a man’s head on a lion’s body), standing 240 feet long and 66 feet tall. The last pyramid was built around 2532-2503 B.C. for Khafre’s son, Pharaoh Menkaure. It was the shortest of the three pyramids in this ancient wonder, standing at only 216 feet tall. It took over 2.3 million blocks of limestone, 100,000 men, and 20 years to construct the greatest architectural achievement in the ancient world. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Jerome on the Attack: Constructing a Polemical Persona Nicole Cleary Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2015 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is of my own composition, and that it contains no material previously submitted for the award of any other degree or professional qualification. Nicole Cleary Signed: ii CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ vii Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. -

THE ENDURING GODDESS: Artemis and Mary, Mother of Jesus”

“THE ENDURING GODDESS: Artemis and Mary, Mother of Jesus” Carla Ionescu A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HUMANITIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO May 2016 © Carla Ionescu, 2016 ii Abstract: Tradition states that the most popular Olympian deities are Apollo, Athena, Zeus and Dionysius. These divinities played key roles in the communal, political and ritual development of the Greco-Roman world. This work suggests that this deeply entrenched scholarly tradition is fissured with misunderstandings of Greek and Ephesian popular culture, and provides evidence that clearly suggests Artemis is the most prevalent and influential goddess of the Mediterranean, with roots embedded in the community and culture of this area that can be traced further back in time than even the arrival of the Greeks. In fact, Artemis’ reign is so fundamental to the cultural identity of her worshippers that even when facing the onslaught of early Christianity, she could not be deposed. Instead, she survived the conquering of this new religion under the guise of Mary, Mother of Jesus. Using methods of narrative analysis, as well as review of archeological findings, this work demonstrates that the customs devoted to the worship of Artemis were fundamental to the civic identity of her followers, particularly in the city of Ephesus in which Artemis reigned not only as Queen of Heaven, but also as Mother, Healer and Saviour. Reverence for her was as so deeply entrenched in the community of this city, that after her temple was destroyed, and Christian churches were built on top of her sacred places, her citizens brought forward the only female character in the new ruling religion of Christianity, the Virgin Mary, and re-named her Theotokos, Mother of God, within its city walls. -

![[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7259/pdf-the-myths-and-legends-of-ancient-greece-and-rome-4397259.webp)

[PDF]The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome

The Myths & Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome E. M. Berens p q xMetaLibriy Copyright c 2009 MetaLibri Text in public domain. Some rights reserved. Please note that although the text of this ebook is in the public domain, this pdf edition is a copyrighted publication. Downloading of this book for private use and official government purposes is permitted and encouraged. Commercial use is protected by international copyright. Reprinting and electronic or other means of reproduction of this ebook or any part thereof requires the authorization of the publisher. Please cite as: Berens, E.M. The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome. (Ed. S.M.Soares). MetaLibri, October 13, 2009, v1.0p. MetaLibri http://metalibri.wikidot.com [email protected] Amsterdam October 13, 2009 Contents List of Figures .................................... viii Preface .......................................... xi Part I. — MYTHS Introduction ....................................... 2 FIRST DYNASTY — ORIGIN OF THE WORLD Uranus and G (Clus and Terra)........................ 5 SECOND DYNASTY Cronus (Saturn).................................... 8 Rhea (Ops)....................................... 11 Division of the World ................................ 12 Theories as to the Origin of Man ......................... 13 THIRD DYNASTY — OLYMPIAN DIVINITIES ZEUS (Jupiter).................................... 17 Hera (Juno)...................................... 27 Pallas-Athene (Minerva).............................. 32 Themis .......................................... 37 Hestia -

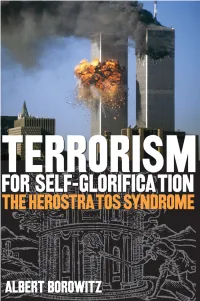

Terrorism for Self-Glorification

Terrorism for Self-Glorification introduction i This page intentionally left blank ii introduction Terrorism for Self-Glorification The Herostratos Syndrome Albert Borowitz The Kent State University Press Kent and London introduction iii © by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio all rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number isbn 0-87338-818-6 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Borowitz, Albert, – Terrorism for self-glorification : the herostratos syndrome / Albert Borowitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. --- (hardcover : alk. paper) ∞ . Terrorism. Violence—Psychological aspects. Aggressiveness. Herostratus. I. Title. .'—dc British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available. iv introduction In memory of Professor John Huston Finley, who, more than half a century ago, first told me about the crime of Herostratos. introduction v This page intentionally left blank vi introduction Contents Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note x Introduction xi The Birth of the Herostratos Tradition The Globalization of Herostratos The Destroyers The Killers Herostratos at the World Trade Center The Literature of Herostratos Since the Early Nineteenth Century Afterword Appendix: Herostratos in Art and Film Notes Index introduction vii This page intentionally left blank viii introduction Acknowledgments First and foremost my thanks go to my wife, Helen, who has contributed immeasurably to Terrorism for Self-Glorification, providing fresh insights into Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, guiding me through mountains of works on modern terrorism, and reviewing my manuscript at many stages. I am also grateful to Dr. Jeanne Somers, associate dean of the Kent State University Libraries, for her ingenuity and persistence in locating rare volumes from the four corners of the world. -

Seven Wonders of the World

Are We There Yet? Seven Wonders of the World Presentation The Seven Wonders of the world in Ancient Era 2 Great Pyramid of Giza ❖ Date of Construction: 2584-2561 BC ❖ Builders: Egyptians ❖ Modern Location: Giza Necropolis, Egypt ❖ It was built for the Pharaoh Khufu ❖ It was the tallest man-made structure in the world for thousands of years until the Lincoln Cathedral ➢ 481 feet tall ❖ It has shrunk about 25 feet due to erosion VIDEO https://youtu.be/TMzouTzim0o 3 Hanging Gardens of Babylon ❖ Date of Construction: 600 BC ❖ Builders: Babylonians/ Assyrians ❖ Modern Location: HIllah or Nineveh Iraq ❖ The gardens were up to 75 feet high and it is thought that the plants tumbled down over a kind of pyramid-shaped stone structure. ❖ Some say they were just a legend. ❖ Although archaeologists have looked, no one has yet found any Video archaeological proof that they really https://youtu.be/DmglKt did exist 4 om7YE Temple of Artemis at Ephesus ❖ Date of Construction: 550 BC and again at 323 BC ❖ Builders: Greeks/ Lydians ❖ Modern Location: Near Selçuk, Turkey ❖ Date of destruction: 356 BC( by Herostratus) and AD 262 (by the Goths) ❖ Some of the columns that were built in Hagia Sophia (a church in Istanbul, Turkey) are thought to have been originally part of the Temple of Artemis Video: ❖ The site where the temple once stood is https://youtu.be/lWbGt now a swamp yxgwbg 5 Statue of Zeus at Olympia ❖ Date of Construction: 435 BC (statue) ❖ Builder: Greeks ❖ Modern Location: Olympia, Greece ❖ Date of destruction:5/6th century AD ❖ It was destroyed by a fire ❖ The statue was constructed with a wooden frame and then was covered in ivory and gold panels. -

Artemis and Virginity in Ancient Greece

SAPIENZA UNIVERSITÀ DI ROMA FACOLTÀ DI LETTERE E FILOSOFIA DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN FILOLOGIA E STORIA DEL MONDO ANTICO XXVI CICLO ARTEMIS AND VIRGINITY IN ANCIENT GREECE TUTOR COTUTOR PROF. PIETRO VANNICELLI PROF. FRANCESCO GUIZZI 2 Dedication: To S & J with love and gratitude. Acknowledgements: I first and foremost wish to thank my tutor/advisor Professor Pietro Vannicelli and Co- Tutor Professor Francesco Guizzi for agreeing to serve in these capacities, for their invaluable advice and comments, and for their kind support and encouragement. I also wish to thank the following individuals who have lent intellectual and emotional support as well as provided invaluable comments on aspects of the thesis or offered advice and spirited discussion: Professor Maria Giovanna Biga, La Sapienza, and Professor Gilda Bartoloni, La Sapienza, for their invaluable support at crucial moments in my doctoral studies. Professor Emerita Larissa Bonfante, New York University, who proof-read my thesis as well as offered sound advice and thought-provoking and stimulating discussions. Dr. Massimo Blasi, La Sapienza, who proof-read my thesis and offered advice as well as practical support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies. Dr. Yang Wang, Princeton University, who proof-read my thesis and offered many helpful comments and practical support. Dr. Natalia Manzano Davidovich, La Sapienza, who has offered intellectual, emotional, and practical support this past year. Our e-mail conversations about various topics related to our respective theses have -

The Coins of Ephesus Part 1

The road to the harbour at Ephesus. (Wikimedia Commons: detail of a photograph taken by Ad Meskens) PHESUS is an ancient ruined city in He was told that a fish and a wild boar Roman Emperor Macrinus minted at ETurkey. It is a few miles from the would show him the place. After landing Ephesus in 217 AD we see Andoklos shore of the Aegean Sea. ( Figure 1 ) It on the coast he fried some fish that he pointing his spear at a very nasty-looking was probably founded by Greeks in about caught, but one of the fish jumped out of boar. ( Figure 2 ) Originally Ephesus had 1000 BC and according to a legend the the pan and started a fire in the dry founder was Androklos, the son of the grass. A boar in the bushes nearby ran king of Athens. He wanted to migrate to from the fire, but Androklos chased it and the coast of Asia Minor and he consulted killed it near mount Koressos, which is an oracle about where he should settle. where he built the city. On a coin of the Figure 2 – Bronze coin of Macrinus (217-218) showing Androklos and a boar. On the reverse the words mean “[a coin] of the Ephesians. Figure 1 – Map of the Aegean Sea showing Ephesus on the west coast Androklos.” (Helios Numismatik GmbH, Auction of Asia Minor. (Wikimedia Commons) 5, Lot 710) Figure 3 – The Temple of Artemis as St Paul would have seen it in the 1 st century AD. (Wikimedia Commons: image created by Cafeennui) a harbour, but with the passage of time ΕΦΕΣΟΣ , is of part icular importance to tourists, especially Christians, and it is the harbour silted up and by about 500 Christians because Saint Paul lived amazing that many of the coins that AD the city could no longer function as there for two years (53 and 54 AD) and circulated there still exist and can be a seaport and trading centre. -

Asia Minor, Modern Turkey

1/11/2015 Dr. Keith Lloyd Associate Professor of English Kent State University © January 4, 2014 A center of pluralistic beliefs and tolerance becomes the center of two significant Christian controversies related to its history. “Ephesus/ Selҫuk” Biblical Sites in Turkey http://www.tourguideinturkey.com/index.php/ephesusselcuk.html Asia Minor, Modern Turkey Ephesus 1 1/11/2015 Oldest places of settlement in the area 5th-3rd millennia Ἔφεσος around Ephesus. King Mursilis II. of the Hittites beat Apasa, 2nd half of 14th century Myceanaean findings on the Ayasuluk Hill. Greeks came to Anatolia and called 11th century themselves Ionian. Androclus settled in Ephesus where the local peple Carian lived. Certain existence of the Sanctuary of 9th century Artemis. 8th century Cimmerian invasion. 7th century Lydians captured Ephesus. Lydian Croesus gained influence in Ephesus : building of the archaic shrine of around 560 Artemis, new layout of the city in the surrounding area. Democracy introduced to Ephesians by around 550 Aristarchus of Athens. The Median general Harpagus took the 546 conrol of this region and Persian supremacy Ephesus joined the Attaic sea alliance. Herostratus burned the Artemis Temple on 466 the very night when Alexander the Great was born. Ephesus Ancient City, House of Virgin Mary, Artemis Temple Basilica of St John and around http://www.ephesus.us/ephesus/ephesus_chronology.htm Έφεσο Alexander the Great liberated all Greek cities and gave privileges to 334 Ephesians building the new temple Ephesus changed its rulers several times during the Diadochian wars. 319-281 The city was renamed as Arsinoeia by King Lysimachus and moved its new side between two mountains. -

1599 the Yom Kippur War and The

#1599 The Yom Kippur War and the Abomination of Desolation – The series of 4’s (fours) from Alexander the Great to Antiochus IV Epiphanes, part 5w, Antiochus IV: Alexander the Great and the destruction of the Temple of Diana at Ephesus, and Antiochus IV and the desecration of the Temple at Jerusalem Key Understanding #1: The destruction of the temple of Diana. According to historical legend, the Temple of Artemis (Diana) at Ephesus was deliberately set aflame by Herostratus, who, setting fire to the wooden frame of the roof, was motivated by the hope of immortalizing his name. This was said to have occurred on the night of July 20-21, 356 B.C., the night that Alexander the Great was born. The Temple of Diana at Ephesus Here is an account from just one of a multitude of sources repeating the story about the historical coincidence of the destruction of the Temple of Artemis (Diana) and the birth of Alexander the Great occurring the same night: The temple of Artemis at Ephesus was destroyed on July 21, 356 B.C., in [an] act of arson committed by Herostratus. According to the story, his motivation was fame at any cost, thus the term herostratic fame. A man was found to plan the burning of the temple of Ephesian Diana so that through the destruction of this most beautiful building his name might be spread through the whole world. The Ephesians, outraged, announced that Herostratus’ name never be recorded. Strabo later noted the name, which is how we know [it] today.