In the Soviet-Turkish Relations (1919-1921)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Araovacik-Danişment (Çanakkale-Balikesir) Çevresinin Jeomorfolofisi

ARAOVACIK-DANIŞMENT (ÇANAKKALE-BALIKESIR) ÇEVRESİNİN JEOMORFOLOFİSİ Doç. Dr. Talat KOÇ* ÖZET Koca Çay Madra Dağı'ndan kaynaklanmakta, Manyas Gölü ve Karadere aracılığıyla Susurluk Çayı'na ulaşmaktadır. Koca Çay batıdan, Balya ve Danışment çevresinden kollar almaktadır. Araovacık-Danışment çevresinden katılan kolların bulunduğu saha, havza özelliğine sahiptir. Bu araştırmada Araovacık-Danışment Havzası ile Koca Çay'ın bu kesiminin jeomorfolojisi incelenmiştir. Araştırma sahasında Alt Miyosenden itibaren oluşan şekiller yaygındır. Araovacık-Danışment çevresi jeolojik, jeomorfolojik ve hidrografik yapısıyla havza özelliğine sahiptir. Araştırma sahası genel hatlarıyla su bölümü çizgisi tarafından sınırlandırılmaktadır. Dağlık alanlarda Alt-Orta ve Üst Miyosen aşınım yüzeyleri yaygındır. Sırtlardan havza tabanına doğru Üst Miyosen aşınım ve birikim yüzeyleri ile geçilmektedir. Üst Miyosen plato yüzeyleri arasına Pliyosen aşınım ve birikim alanları sokulmaktadır. Araovacık-Danışment Havzası genç tektonik (neotektonik) olaylardan fazla etkilenmiştir. Araovacık-Danışment Havzası, tabanı fazla gelişmemiş bir grabendir. Graben tabanında birbirine antesedant boğazlar ile bağlanmış küçük düzlükler bulunmaktadır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Güney Marmara, graben, horst, antesedant boğaz. Çanakkale 18 Mart Üniversitesi, Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi, Coğrafya Bölümü Öğretim Üyesi Talat KOÇ 2 GEOMORPHOLOGY OF ENVIRONMENT OF ARAOVACIK-DANIŞMENT(ÇANAKKALE-BALIKESİR) ABSTRACT Koca stream arises from Madra Mountain and reaches Susurluk stream with by the help of Manyas Lake and Karadere. Koca stream takes branches from environment of Balya and Danışment from west. The area, which the branches were added from environment of Araovacik-Danisment has a basin characteristic. Geomorphology of Araovacik-Danisment basin and this part of Koca stream were studied in this research. Landforms, which existed from Lover Miosen are widespread in research area. Environment of Araovacik-Danisment have a basin characteristic structure of geology, geomorphology and hydrology. -

Information, Mining Investment Guide 2019

Summary With its developing economy, Turkey is becoming one of the major centers of world economy. Global enterprises prioritize Turkey in their investment decisions and gain advantages thanks to elements such as Turkey’s geographical location, natural resources, and trained labor force. Trained labor force; land-sea-air transport with multiple alternatives; proximity to metropoles and many such advantages underline Balıkesir in hosting sustainable investments. This work aims to promote current investment environment in order to enable Balıkesir to take a bigger role in Turkey, which is becoming a center of attraction with new investments. This guide promotes the investment environment for mining sector in Balıkesir and lists the advantages investors will benefit by investing in Balıkesir. From the potential of Balıkesir in mining sector to its logistics opportunities, from regional incentives provided by the Ministry of Industry and Technology to services provided by South Marmara Development Agency, a wide range of pre-investment information is given in detail in the guide. Apart from this Mining Investment Guide, investment guides on other sectors such as Agriculture, Tourism, Industry, and Energy were prepared and presented into potential investors’ service. In addition to these, South Marmara Development Agency also provides support services with its technical infrastructure and its expert staff, and supports all investments in Balıkesir as a solution partner. While we hope that this Guide proves useful to you; we would like to inform you that you can always benefit from the extensive support services our Investment Support Office gladly provides in order to help you realize your investments. SOUTH MARMARA DEVELOPMENT AGENCY Balıkesir in Mining Investments Balıkesir province has a great potential in mining investments. -

1768-1830S a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate

A PLAGUE ON BOTH HOUSES?: POPULATION MOVEMENTS AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE ACROSS THE OTTOMAN-RUSSIAN BLACK SEA FRONTIER, 1768-1830S A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrew Robarts, M.S.F.S. Washington, DC December 17, 2010 Copyright 2010 by Andrew Robarts All Rights Reserved ii A PLAGUE ON BOTH HOUSES?: POPULATION MOVEMENTS AND THE SPREAD OF DISEASE ACROSS THE OTTOMAN-RUSSIAN BLACK SEA FRONTIER, 1768-1830S Andrew Robarts, M.S.F.S. Dissertation Advisor: Catherine Evtuhov, Ph. D. ABSTRACT Based upon a reading of Ottoman, Russian, and Bulgarian archival documents, this dissertation examines the response by the Ottoman and Russian states to the accelerated pace of migration and spread of disease in the Black Sea region from the outbreak of the Russo-Ottoman War of 1768-1774 to the signing of the Treaty of Hünkar Iskelesi in 1833. Building upon introductory chapters on the Russian-Ottoman Black Sea frontier and a case study of Bulgarian population movements between the Russian and Ottoman Empires, this dissertation analyzes Russian and Ottoman migration and settlement policies, the spread of epidemic diseases (plague and cholera) in the Black Sea region, the construction of quarantines and the implementation of travel document regimes. The role and position of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia as the “middle ground” between the Ottoman and Russian Empires -

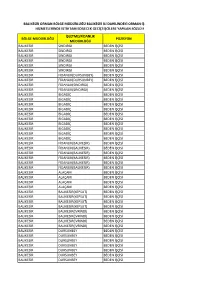

Ad Soyad Hizmet Puanı Eski Görev İlçesi Görev Yeri Branşı Atandığı

BALIKESİR İL MİLLÎ EĞİTİM MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ ÖĞRETMENLERİN 2021 YILI İL İÇİ İSTEĞE BAĞLI YER DEĞİŞTİRME SONUÇ LİSTESİ (Yer Değiştirme Sonuç Listesi bilgilendirme amaçlıdır. Gerekli kontroller yapıldıktan ve Valilik Oluru alındıktan sonra sonuçlar kesinlik kazanacaktır.) Hizmet Eski Görev Ad Soyad Görev Yeri Branşı Atandığı İlçe Atandığı Kurum Sıra No Puanı İlçesi 1 ASLI KOÇ 121 SAVAŞTEPE Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Anadolu Lisesi Almanca ALTIEYLÜL Balıkesir Cumhuriyet Anadolu Lisesi 2 TUĞBA GÜLER 87 ERDEK Erdek Anadolu Lisesi Almanca BANDIRMA Kemal Pireci Anadolu Lisesi 3 SEMRA YÜCEL 462 MARMARA Marmara Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi Beden Eğitimi MARMARA Marmara Halk Eğitimi Merkezi Burhaniye Ticaret Odası Özel Eğitim Uygulama Okulu 4 MURAT AKTEPE 416 BURHANİYE Beden Eğitimi BURHANİYE Burhaniye Atatürk Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi III. Kademe 5 MEHMET TUNCAY DEMİRCAN 267 BANDIRMA Edincik Recep Gencer Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi Beden Eğitimi BANDIRMA Fatih Ortaokulu 6 RAMAZAN YAZGAN 267 İVRİNDİ Şehit Turan Kurt Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi DURSUNBEY Akbaşlar Ortaokulu 7 GÜLŞAH ERTAN 241 BANDIRMA Bandırma Atatürk Özel Eğitim Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi BANDIRMA Aksakal Umut Akkaya Ortaokulu 8 SEMİH ÖZKARAL 185 SINDIRGI Yüreğil Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi İVRİNDİ Soğanbükü Müdafa-i Hukuk Ortaokulu 9 AHMET BİRGÜN 121 MARMARA Avşa Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi ERDEK Karşıyaka Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 10 BÜŞRA İLDAN 87 EDREMİT Yolören Esin Akpınar Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi İVRİNDİ KAYAPA ORTAOKULU 11 AYKUT ÖZKAN 82 SINDIRGI Gölcük Ortaokulu Beden Eğitimi SINDIRGI Sındırgı Makbule Efe Anadolu Lisesi 12 SİNAN ÖNAL 177 GÖNEN Buğdaylı Ortaokulu Bilişim Teknolojileri BURHANİYE Şehit Mustafa Serin Ortaokulu 13 NURETTİN YORULMAZ 138 SINDIRGI Sındırgı Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi Bilişim Teknolojileri SINDIRGI Cumhuriyet Ortaokulu 14 EYLÜL ESİNBAY 113 SAVAŞTEPE Necip Fazıl Kısakürek Anadolu Lisesi Bilişim Teknolojileri SUSURLUK Susurluk Anadolu Lisesi 15 HAKAN ERDEMLİ 397 MANYAS Manyas Anadolu Lisesi Biyoloji BANDIRMA Bandırma Anadolu Lisesi 16 İBRAHİM COŞKUN 395 ALTIEYLÜL 100. -

Balikesir Orman Bölge Müdürlüğü Balikesir Ili Dahilindeki Orman Iş Hizmetlerinde Istihtam Edilecek Geciçi Işcilere Yapilan Sözlü M

BALIKESİR ORMAN BÖLGE MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ BALIKESİR İLİ DAHİLİNDEKİ ORMAN İŞ HİZMETLERİNDE İSTİHTAM EDİLECEK GECİÇİ İŞCİLERE YAPILAN SÖZLÜ M İŞLETME/FİDANLIK BÖLGE MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ POZİSYON MÜDÜRLÜĞÜ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR SINDIRGI BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(DURSUNBEY) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(DURSUNBEY) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(SINDIRGI) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(SINDIRGI) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRBİGADİÇ BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİRFİDANLIK(BALIKESİR) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR ALAÇAM BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR ALAÇAM BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR ALAÇAM BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR ALAÇAM BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(KEPSUT) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(KEPSUT) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(KEPSUT) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(KEPSUT) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(İVRİNDİ) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(İVRİNDİ) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(İVRİNDİ) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR BALIKESİR(İVRİNDİ) BEDEN İŞÇİSİ BALIKESİR DURSUNBEY -

Geochemical and Isotopic Characteristics of the Balikesir

Proceedings World Geothermal Congress 2010 Bali, Indonesia, 25-29 April 2010 Geochemical and Isotopic Characteristics of the Balıkesir Thermal Waters, Turkey Halim Mutlu and Ahmet Kılıç Eskisehir Osmangazi University, Department of Geological Engineering, Eskisehir, 26480, Turkey [email protected] Keywords: Water-rock interaction, stable isotope, In this study geochemical characteristics of the Balıkesir geothermometry, Balikesir thermal waters, Turkey. thermal waters are investigated on the basis of various water-rock interaction models and the equilibrium states of ABSTRACT geothermal minerals and reservoir temperatures of thermal waters are examined. Moreover, the source of water and its The Balıkesir geothermal waters in northwestern Turkey are dissolved constituents are discussed. represented by discharge temperatures in the range of 32- 99ºC and TDS contents between 327 and 2578 mg/l. The 2. WATER CHEMISTRY waters in the region are of Na-SO4, Na-HCO3 and Ca-HCO3 type character. It was determined that the solubility of silica A total of 21 thermal water samples were collected from the in most of waters is controlled by the chalcedony phase. geothermal wells and springs in the Balıkesir region in Equilibrium states of the Balıkesir thermal waters studied by August 2005. Locations of the water samples are shown in means of the Na-K-Mg-Ca diagram, mineral saturation Figure 1. Waters of the Gönen, Manyas, Pamukçu, Bigadiç calculations and activity diagrams approximate a reservoir and Edremit areas are collected from wells while those of temperature of about 120ºC. Most waters are found to be the Ekşidere, Sındırgı, Balya and Susurluk fields are equilibrated with calcite, chalcedony±quartz and muscovite sampled from hot springs. -

Yaklaşık, Balıkesir'e 50 Km Uzaklıkta Olan Balya Madeni İlçenin Belediye

GİRİŞ ÖNCEKİ ÇALİŞMALAR Yaklaşık, Balıkesir'e 50 Km uzaklıkta olan Balya madenine birçok yabancı ve yerli uz- Balya madeni İlçenin Belediye sınırlan içinde manların geldiği, çevrenin jeolojisi ve maden ve yakınında bulunmaktadır (Şekil 1), Eski çağ- yatağı hakkında yazılar yazıldığı bilinir. Madenin lardan bu yana varlığı bilinen maden Orta çağda modern işletmeciliğe geçiş yılları ile birlikte Periklea zamanından beri işletilmektedir. Bu ma- çevre jeolojisine de ilginin arttığı görülür. Baş- dende modern işletmeciliğe 1880 yılında «Soci- langıçtaki çalışmalar genellikle yörenin stratig- été desmines de Balya-'Karaaydın» adında bir refik sorunlarına yöneliktir. Fransız şirketi başlamıştır. Bu işletme 1939 yı- lına dek sürmüştür. 1913 yılında en yüksek üre- P. de TchPhatcheff (1886) daha ziyade vol- tim düzeyine erişmiş olup 140.300 ton ham cev- kanik kayaçlar İle ilgilenmiş; Neumayr (1886) bu her ve 13,980 ton kurşun üretilmiştir. Şirketin civardan toplanan ve kendisine götürülen fosil- modern İşletmeciliğe geçmesinden sonra 4 mil- ler İle İlgilenmiş ve ilk defa Balya civarmda Üst yon ton civarında cevher İşlediği ve bundan da Trigas'dan bahsetmiştir. 400,000 ton metal kurşun ürettiği tahmin edil- Weiss ve Berg (1901), "Maden yatağının, mektedir. ojitli andezitler İle Kanbonifer yaşlı düşündük- leri kireotaşları arasında «metamorflk bir doka- nak» ile ilişkili olduğunu düşünmüşlerdir. Enderle (1900), Balya civarındaki kireçtaş- iarımn ilk ayrıntılı incelemesini yapmıştır. Per- mo - Karbonifer yaşı vermiştir, Phllipson (1915), Paleozoyik yaşlı kayaçlar ile, civarda bulunan, volkanik kayaçlar arasında ilişki kurmaya çalışmıştır, Koverîko (1940) cevher yatağını «porflrik cevher, kireçtaşı içindeki cevher, çökel kayaç» lann tabakaları arasındaki cevher ve dokanak damarlar» diye dört tipe ayırmıştır. Aygen (1956), dokanak tipi cevherleşmenin Balya'da önemli olmadığını Permiyenin, kumta- şj ve kireçtaşı fasiyeslnde olduğunu, Triyas for- masyonlarını da şist, kumtaşı, çakıltaşı diye ayı- rır. -

Muhtarlarimiz No Ilçe Mahalle Adi Soyadi 1

MUHTARLARIMIZ NO İLÇE MAHALLE ADI SOYADI 1 ALTIEYLÜL Altıeylül Emine ÇETİNASLAN 2 ALTIEYLÜL Bağalan Rabiye SAĞLAM 3 ALTIEYLÜL Kabaklı Cemile ALKAN 4 ALTIEYLÜL Kasaplar Gönül BAŞÇİVİ 5 ALTIEYLÜL Pilevne Neslihan ATLI 6 ALTIEYLÜL Sütlüce Sema SAÇAKLI 7 ALTIEYLÜL 1.Gündoğan Kadir YEŞİL 8 ALTIEYLÜL 2.Gündoğan Nihat EMER 9 ALTIEYLÜL Akarsu Musa DOĞAÇ 10 ALTIEYLÜL Akçaköy Şerafettin DEMİRCİ 11 ALTIEYLÜL Aliağa Vedat AKAY 12 ALTIEYLÜL Aslıhan Erdoğan ATALAY 13 ALTIEYLÜL Aslıhan tepeciği Ahmet KARAGÖZ 14 ALTIEYLÜL Ataköy Ahmet ALTAY 15 ALTIEYLÜL Atköy Celal TURKAN 16 ALTIEYLÜL Aynaoğlu Gencer POYRAZ 17 ALTIEYLÜL Ayşebacı Recep KORKMAZ 18 ALTIEYLÜL Ayvacık Orhan DÜÇER 19 ALTIEYLÜL Ayvatlar Kerim TEHLİ 20 ALTIEYLÜL Bahçedere Mücahit YÜKSEL 21 ALTIEYLÜL Bahçelievler Hidayet ERSÖZGİL 22 ALTIEYLÜL Balıklı Halil TIĞLI 23 ALTIEYLÜL Bayat Hüseyin ÖZTÜRK 24 ALTIEYLÜL Bereketli Mustafa BALCAN 25 ALTIEYLÜL Beşpınar Sezayi ERKAN 26 ALTIEYLÜL Boğatepe Erdem BOZCA 27 ALTIEYLÜL Bozen Kadri TEKİN 28 ALTIEYLÜL Büyükbostancı Kurban CEYLAN 29 ALTIEYLÜL Çakıllık Günay YILDIZ 30 ALTIEYLÜL Çamköy Cüneyt ÇAM 31 ALTIEYLÜL Çandır Yusuf PARLAK 32 ALTIEYLÜL Çayırhisar Mustafa SÜREN 33 ALTIEYLÜL Çınarlıdere Davut TUNA 34 ALTIEYLÜL Çiftçidere Süleyman GÖKÇE 35 ALTIEYLÜL Çiftlikköy Ali YILDIRIM 36 ALTIEYLÜL Çinge Ali KILINÇ 37 ALTIEYLÜL Çukurhüseyin Hasan SOLAK 38 ALTIEYLÜL Dallımandıra Ali ŞAHİN 39 ALTIEYLÜL Dedeburnu Eyüp BAYGÜL 40 ALTIEYLÜL Dereçiftlik Emin EFE 41 ALTIEYLÜL Dereköy Mehmet SON 42 ALTIEYLÜL Dinkçiler Mustafa SANGÜL 43 ALTIEYLÜL Dişbudak Sezai ÇAKICI 44 ALTIEYLÜL -

Academic Studies in Engineering - Ii

ACADEMIC STUDIES IN ENGINEERING - II Edtor : PROF. DR. REYHAN İRKİN İmtiyaz Sahibi / Publisher • Yaşar Hız Genel Yayın Yönetmeni / Editor in Chief • Eda Altunel Editör / Edıtor • Prof. Dr. Reyhan İrkin Kapak & İç Tasarım / Cover & Interior Design • Karaf Ajans Birinci Basım / First Edition • © Haziran 2020 ISBN • 978-625-7884-57-0 © copyright Bu kitabın yayın hakkı Gece Kitaplığı’na aittir. Kaynak gösterilmeden alıntı yapılamaz, izin almadan hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. The right to publish this book belongs to Gece Kitaplığı. Citation can not be shown without the source, reproduced in any way without permission. Gece Kitaplığı / Gece Publishing Türkiye Adres / Turkey Address: Kızılay Mah. Fevzi Çakmak 1. Sokak Ümit Apt. No: 22/A Çankaya / Ankara / TR Telefon / Phone: +90 312 384 80 40 web: www.gecekitapligi.com e-mail: [email protected] Baskı & Cilt / Printing & Volume Sertifika / Certificate No: 47083 Academic Studies in Engineering - II Edıtor Prof. Dr. Reyhan İrkin TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE ON SOIL-STRUCTURE INTERACTION: ARTIFICIAL NEURAL NETWORKS AND SUPPORT VECTOR MACHINES Ahmet Emin KURTOĞLU .............................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 CODE GENERATOR MODEL FOCUSED ON RELATIONAL DATA MODEL AND USER MOVEMENT Çağla EDİZ ...................................................................................................... 15 Chapter 3 EMBEDDED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATIC LICENSE PLATE RECOGNITION Ercan BULUŞ ................................................................................................. -

Balikesir'in Sosyo-Ekonomik Yapisi

T.C. SAKARYA ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ BALIKES İR’İN SOSYO-EKONOM İK YAPISI YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Hüdaverdi ÖZ ŞEN Enstitü Ana Bilim Dalı: Sosyoloji Tez Danı şmanı: Yard. Doç. Dr. Fikri OKUT EYLÜL 2008 T.C. SAKARYA ÜN İVERS İTES İ SOSYAL B İLİMLER ENST İTÜSÜ BALIKES İR’İN SOSYO-EKONOM İK YAPISI YÜKSEK L İSANS TEZ İ Hüdaverdi ÖZ ŞEN Enstitü Ana Bilim Dalı: Sosyoloji Tez Danı şmanı: Yard. Doç. Dr. Fikri OKUT Bu tez 10/09/2008 tarihinde a şağıdaki jüri tarafından oyçoklu ğu ile kabul edilmi ştir. _____________ ____________ ____________ Jüri Ba şkanı Jüri Üyesi Jüri Üyesi Kabul Kabul Kabul Red Red Red Düzeltme Düzeltme Düzeltme BEYAN Bu tezin yazılmasında bilimsel ahlak kurallarına uyuldu ğu, ba şkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel normlara uygun olarak atıfta bulunulduğunu, kullanılan verilerde herhangi bir tahrifat yapılmadı ğını, tezin herhangi bir kısmının bu üniversite veya ba şka bir üniversitedeki ba şka bir tez çalı şması olarak sunulmadı ğını beyan ederim. Hüdaverdi ÖZ ŞEN ÖNSÖZ Sakarya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü‟nde, Sosyoloji Anabilim Dalında Yüksek Lisans tezi olarak yaptığım çalıĢmada Balıkesir‟in Sosyo-Ekonomik Durumu üzerinde durulmuĢtur. Tez konusunun seçiminde ve çalıĢmalarım esnasında bana yardımcı olan, tezimin düzenlenmesinde yardımlarını esirgemeyen Sayın Hocam Yard.Doç.Dr.Fikri OKUT‟a teĢekkür ederim. AraĢtırmada ele aldığım konular arasında Balıkesir‟in kurulması, Ģehrin tarihi, Ģehrin nüfus özellikleri, Ģehrin baĢlıca ekonomik fonksiyonları ve bunların dağılıĢ sahalarıyla Ģehrin önemli sorunları yer almaktadır. Bana hazırlamıĢ olduğum bu tez çalıĢmamda yardımcı olan herkese yakın alaka ve yardımlarından dolayı teĢekkür ederim. Hüdaverdi ÖZġEN 10.09.2008 ĠÇĠNDEKĠLER TABLO LĠSTESĠ ........................................................................................................... -

Ilbank-2018-Faaliyet-Raporu-Eng.Pdf

The Finance Bank should be established for the public services of the municipalities in the construction and installation of the cities. ILLER BANK2018 Contents SECTION ONE SECTION TWO SECTION THREE SECTION FOUR Presentation Bank’s Annual Activities Management and Corporate Financial Information 7 Agenda of the Ordinary General 22 2018 Investment and Financing Program Governance Practices and Risk Management Assembly Meeting 23 Works carried out with 100% Credits Financed by Bank Equity. 8 Corporate Profile 24 Bank’s 2018 Annual Activities 54 Board of Directors 69 Audit Board Report 11 Message From the Minister of 26 Project to Support the Infrastructure of Municipalities (BELDES) 56 Audit Committee 70 Audit Committee’s Assessment Of The Operation Of The Environment and Urbanization 26 Water and Sewer Systems Infrastructure Project (SUKAP) 57 Information On Audit Committee Internal Control, Internal Audit, And Risk Management 13 Message from the Chairman 27 Works Being Conducted With Appropriations Made From the Bank’s Profits 58 Information on General Manager Systems and Its Statement Concerning Activities in Year 2018 15 Message from the General Manager 30 Ministry of Environment and Urbanization Ministry with 60 Information On Internal Systems Unit Directors 74 Independent Audit Report 16 Our Corporate Message Works made under the Protocols 61 Organizational Chart Of Iller Bank 78 Iller Bank Non-Consolidated Financial Report for the Year 18 Summary Financial Results 32 Resource Development Activities and Urban Transformation Projects -

Balıkesir Üniversitesi

T.C. BALIKESİR ÜNİVERSİTESİ TURİZM ENVANTERİ VE STRATEJİ ÇALIŞMASI HAZIRLAYANLAR DOÇ. DR. SEBAHATTİN KARAMAN DOÇ. DR. BURHAN AYDEMİR ARŞ. GÖR. SULTAN NAZMİYE KILIÇ TURİZM FAKÜLTESİ GÜNEY MARMARA KALKINMA AJANSI VE BALIKESİR ÜNİVERSİTESİ KURUMSAL İŞ BİRLİĞİ PROTOKOLÜ KAPSAMINA GÖRE HAZIRLANMIŞTIR. KATKILARINDAN DOLAYI BALIKESİR İL KÜLTÜR VE TURİZM MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE TEŞEKKÜR EDERİZ. 1 EYLÜL-2019 İÇİNDEKİLER 1. BALIKESİR KENT MERKEZİ (ALTIEYLÜL VE KARESİ İLÇELERİ) .................. 6 1.1. ALTIEYLÜL ................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. Doğal Çekim Unsurları .......................................................................................... 6 1.1.2. Kültür Varlıkları ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1.3. Ulaşım .................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.4. Arz Verileri ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2. KARESİ ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1. Doğal Çekim Unsurları .......................................................................................... 7 1.2.2. Kültür Varlıkları ..................................................................................................... 7 1.2.3. Ulaşım .................................................................................................................