DIVERCITIES: Dealing with Urban Diversity: the Case of Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward City Charters in Canada

Journal of Law and Social Policy Volume 34 Toronto v Ontario: Implications for Canadian Local Democracy Guest Editors: Alexandra Flynn & Mariana Article 8 Valverde 2021 Toward City Charters in Canada John Sewell Chartercitytoronto.ca Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp Part of the Law Commons Citation Information Sewell, John. "Toward City Charters in Canada." Journal of Law and Social Policy 34. (2021): 134-164. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol34/iss1/8 This Voices and Perspectives is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Social Policy by an authorized editor of Osgoode Digital Commons. Sewell: Toward City Charters in Canada Toward City Charters in Canada JOHN SEWELL FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS, there has been discussion about how cities in Canada can gain more authority and the freedom, powers, and resources necessary to govern their own affairs. The problem goes back to the time of Confederation in 1867, when eighty per cent of Canadians lived in rural areas. Powerful provinces were needed to unite the large, sparsely populated countryside, to pool resources, and to provide good government. Toronto had already become a city in 1834 with a democratically elected government, but its 50,000 people were only around three per cent of Ontario’s 1.6 million. Confederation negotiations did not even consider the idea of conferring governmental power to Toronto or other municipalities, dividing it instead solely between the soon-to-be provinces and the new central government. -

Enhancing Safety At

Branching Out Fall 2019 Enhancing Safety at ESS Walking into our South Adult Day Program, you will be immediately greeted by friendly smiles and cheerful waves from staff, volunteers and seniors attending program. Located in a quiet residential area of South Etobicoke, this program provides a welcoming, inclusive and comfortable home-like space which supports the health and daily living needs of adults and seniors living with Alzheimer's and other dementias. Our program is a special place and a much-needed community resource. With the help of funding from the Central Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) and fundraising dollars from Home Instead Foundation of Canada's 2018 GIVE65 online giving campaign, we have been able to make safety improvements, as well as enhancements to the daily comfort and enjoyment of the individuals attending the program. Using funding received from the Central LHIN, we have: ■ Installed coded security systems to prevent seniors attending the program from wandering outside unattended and emergency call systems in the washrooms; ■ Replaced aging furniture with durable, senior-friendly chairs which are easy for staff to slide and provide assistance, and for seniors to safely move from a seated to standing position; ■ Hired a local artist “Murals by Marg” through Lakeshore Arts to paint a beautiful mural to camouflage door exits and divert seniors seeking an exit. Before After Continued on next page Continued from cover With the donations raised through the support of our local Home Instead Senior Care Chapter (Etobicoke & Mississauga) and GIVE65, we have begun the process of landscaping the back yard to create a safe and usable outdoor program space. -

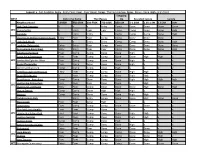

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Experiences of Socio-Spatial Exclusion Among Ghanaian Immigrant Youth in Toronto: a Case Study of the Jane-Finch Neighbourhood

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-28-2012 12:00 AM Experiences of Socio-Spatial Exclusion Among Ghanaian Immigrant Youth in Toronto: A Case Study of the Jane-Finch Neighbourhood Mariama Zaami The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Godwin Arku The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Joseph Mensah The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Geography A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Mariama Zaami 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation Zaami, Mariama, "Experiences of Socio-Spatial Exclusion Among Ghanaian Immigrant Youth in Toronto: A Case Study of the Jane-Finch Neighbourhood" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 604. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/604 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPERIENCES OF SOCIO-SPATIAL EXCLUSION AMONG GHANAIAN IMMIGRANT YOUTH IN TORONTO: A CASE STUDY OF THE JANE andFINCH NEIGHBOURHOOD (Spine Title: Socio-Spatial Exclusion among Ghanaian Immigrant Youth) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by Mariama Zaami Graduate Program in Geography A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies Western University London, Ontario, Canada © Mariam Zaami 2012 WESTERN UNIVERSITY School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Joint-Supervisor Examiners _____________________________________ _______________________________ Dr. -

Fixer Upper, Comp

Legend: x - Not Available, Entry - Entry Point, Fixer - Fixer Upper, Comp - The Compromise, Done - Done + Done, High - High Point Stepping WEST Get in the Game The Masses Up So-called Luxury Luxury Neighbourhood <$550K 550-650K 650-750K 750-850K 850-1M 1-1.25M 1.25-1.5M 1.5-2M 2M+ High Park-Swansea x x x Entry Comp Done Done Done Done W1 Roncesvalles x Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High Parkdale x Entry Entry x Comp Comp Comp Done High Dovercourt Wallace Junction South Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done x High Park North x x Entry Entry Comp Comp Done Done High W2 Lambton-Baby point Entry Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done Done Done Done Runnymede-Bloor West Entry Entry Fixer Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Caledonia-Fairbank Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Corso Italia-Davenport Fixer Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High High x W3 Keelesdale-Eglinton West Fixer Comp Comp Done Done High x x x Rockcliffe-Smythe Fixer Comp Done Done Done High x x x Weston-Pellam Park Comp Comp Comp Done High x x x x Beechborough-Greenbrook Entry Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x BriarHill-Belgravia x Fixer Comp Comp Done High High x x Brookhaven--Amesbury Comp Comp Done Done Done High High High high Humberlea-Pelmo Park Fixer Fixer Fixer Done Done x High x x W4 Maple Leaf and Rustic Entry Fixer Comp Done Done Done High Done High Mount Dennis Comp Comp Done High High High x x x Weston Comp Comp Done Done Done High High x x Yorkdale-Glen Park x Entry Entry Comp Done Done High Done Done Black Creek Fixer Fixer Done High x x x x x Downsview Fixer Comp -

Jane Finch Mission Centre

JANE FINCH MISSION CENTRE Feasibility Study & Business Case Report For the University Presbyterian Church unit a architecture inc. / February 05, 2014 PG TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Tables & Figures 6 0.0 Introduction 0.1 The Need for a Feasibility Study and Business Case 0.2 Objectives 0.3 Vision 10 1.0 Site Description 1.1 Development Characteristics 1.2 Environmental Analysis 1.3 Traffic Analysis 1.4 Regulations and Environmental Issues 1.5 Site Analysis 1.6 Zoning Code Analysis 1.7 Building Code Analysis 20 2.0 Case Studies 2.1 Urban Arts 2.2 Evangel Hall Mission 2.3 Pathways to Education 2.4 Regent Park School of Music 28 3.0 Environment 3.1 Priority Investment Neighbourhood 3.2 Housing 3.3 Conflict 36 4.0 Service Infrastructure 4.1 Access to Service Providers 4.2 Music Services 42 5.0 Investment Options 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Existing Facilities Review 5.3 Existing Church Building Use 5.4 New Investment 5.5 Schematic Design 60 6.0 Business Models 6.1 UPC Designs-Finances-Builds-Operates Facility 6.2 UPC Designs-Finances-Builds New Facility and Operates Church, Third Party Operates Nutritional, Homework and Music Services 6.3 New Jane Finch Mission Board Designs-Finances-Builds and Operates Facility 6.4 Sponsorships 6.5 Conclusion 2 66 7.0 Financial Projections 7.1 LEED Cost-Benefit Analysis 7.2 Capital Costs 7.3 Revenue Centres 7.4 Operating Expenses 7.5 Five-Year Pro-forma Projections 7.6 Project Costs Breakdown 78 8.0 Implementation 8.1 Implementation of the Project 82 9.0 Recommendations 9.1 Alternative 1: Do not proceed with construction of the Jane Finch Mission Centre. -

Tree Canopy Study 201

IE11.1 - Attachment 2 Tree Canopy Study 201 Prepared by: KBM Resources Group Lallemand Inc./BioForest Dillon Consulting Limited 8 With Special Advisors Peter Duinker and James Steenberg, Dalhousie University 2018 Tree Canopy Study Consulting Team Lallemand Inc./BioForest Allison Craig, MFC John Barker, MFC KBM Resources Group Rike Burkhardt, MFC, RPF Ben Kuttner, PhD, RPF Arnold Rudy, MScF Dillon Consulting Limited David Restivo, HBSc, EP John Fairs, HBA Sarah Galloway, HBES Merrilees Willemse, HBA, MCIP, RPP Dalhousie University (Special Advisors) Peter Duinker, PhD James Steenberg, PhD Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the field crews, who recorded the i-Tree data used to generate many of the findings in this report: Lallemand Inc./BioForest: Ahmad Alamad, Laura Brodey, George Chen, Jessica Corrigan, Aurora Lavender, Julia Reale Dillon Consulting Ltd: Trevor Goulet Our thanks go to the City of Toronto Steering Committee members who provided valuable insight and expertise. Daniel Boven, Acting Manager Beth McEwen, Manager Forestry Policy and Planning Forest & Natural Area Management Connie Pinto, Program Standards & Carol Walker, Manager Development Officer Urban Forestry – EWMS Project Forestry Policy and Planning Raymond Vendrig, Manager Ryan Garnett, Manager Urban Forestry Renewal Geospatial Data Integration & Access Page i of 270 2018 Tree Canopy Study Our thanks go also to the key experts who provided input on the draft key findings. Amory Ngan, Project Manager, Tree Planting Strategy, Urban Forestry Andrew Pickett, Urban Forestry Coordinator (A), Urban Forestry Christine Speelman, Sr. Project Coordinator (A), Urban Forestry David Kellershohn, Manager, Stormwater Manager, Toronto Water Jane Welsh, Project Manager, Zoning Bylaw & Environmental Planning, City Planning Jane Weninger, Sr. -

Orking Rough, Living Poor

Working Rough, Living Poor Employment and Income Insecurities faced by Racialized Groups and their Impacts on Health Published by Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services, 2011 Study funded by: To be cited as: Wilson, R.M., P. Landolt, Y.B. Shakya, G. Galabuzi, Z. Zahoorunissa, D. Pham, F. Cabrera, S. Dahy, and M-P. Joly. (2011). Working Rough, Living Poor: Employment and Income Insecurities Faced by Racialized Groups in the Black Creek Area and their Impacts on Health. Toronto: Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services. The content for this report was collaboratively analyzed and written by the core team of the Income Security, Race and Health research working group. The research was designed and implemented with valuable feedback from all our Advisory Committee members and other community partners (see list in Acknowledgement section) The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of The Wellesley Institute or the Metcalf Foundation. Requests for permission and copies of this report should be addressed to: Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services 500-340 College Street Toronto, ON M5S 3G3 Telephone: (416) 324-8677 Fax: (416) 324-9074 www.accessalliance.ca © 2011 Access Alliance Multicultural Health and Community Services About the Income Security, Race and Health Research Working Group The Income Security, Race and Health (ISRH) Research Working Group is a interdisciplinary research group comprising of academics, service providers, and peer researchers interested in examining racialized economic and health inequalities. The group was established in Toronto in 2006 under the leadership of Access Alliance. The key goals of the ISRH team are to investigate the systemic causes of growing racialized inequalities in employment and income, and to document the health impacts of these inequalities. -

Community Conversations: North York West Sub-Region

Central LHIN System Transformation Sub-region Planning Community Conversations: North York West Sub-region April 5, 2017 Setting the Stage for Today’s Discussions Kick off sub-region planning & share the Central LHIN strategy; Bring sub-region communities together to strengthen relationships through collaborative networking; Listen and reflect upon experiences of patients and providers as they move through the system; Create a common understanding of sub-regional attributes related to their communities and populations; Generate greater context of sub-region needs and attributes through collaborative discussion; Set the stage to co-create the system collectively to identify gaps in care continuity during transitions 2 Central LHIN Community Conversation North York West Sub-region Agenda Time Item Presenters 7:45 to 8:30 am Registration & Light Refreshments Sub Region Community Wall 8:30 am Overview of the Day Welcome & Kick Off Kim Baker Central LHIN Sub-region Strategy: Transitions Chantell Tunney 9:50 am Sharing Experiences in Care Guest Speaker: Central LHIN Resident Cottean Lyttle Guest Speaker: Care Provider Dr. Jerome Liu 9:50 pm BREAK 10:00 am Building a Foundation: Information Eugene Wong 11:00 am Filling in the Gaps Group Work 11:25 am Wrap Up & Next Steps Chantell Tunney 3 Integrated Health Service Plan 2016 - 2019 4 Sub-region Strategy Building momentum, leveraging local strengths and co-designing innovative approaches to care continuity 5 Population Health – What does it mean to take a Population Health approach? Population health allows us to address the needs of the entire population, while reminding us that special attention needs to be paid to existing disparities in health. -

The New Geography of Office Location and The

Prepared by: Canadian Urban Institute The New Geography of Office Location 555 Richmond St. W., Suite 402, PO Box 612 and the Consequences of Toronto, ON M5V 3B1 Canada Business as Usual in the GTA 416-365-0816 416-365-0650 [email protected] This reportMarch has 2011 been prepared for the Toronto Office Coalition, March 18, 2011. http://www.canurb.org Research Team: Canadian Urban Institute Glenn R. Miller, Vice President, Education & Research, FCIP, RPP Iain Myrans, Senior Planner, MCIP, RPP Juan Carlos Molina, Geospatial Analyst, MSA Thomas Sullivan, GIS & Policy Analyst, B Sc Danielle Berger, GIS Research Assistant Mike Dror, GIS Research Assistant Real Estate Search Corporation Iain Dobson, Principal & Senior Associate, Canadian Urban Institute Hammersmith Communications Philippa Campsie, Principal & Senior Associate, Canadian Urban Institute All photography in this document by Iain Myrans. This report has been prepared for the Toronto Office Coalition, March 18, 2011. Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Summary of Recommendations.............................................................................................................. 7 1. Business Competitiveness in the GTA, Five Years On............................................................................. 9 2. Changes and trends since 2005 ............................................................................................................. -

Humber Summit Middle School ADDRESS: 60 Pearldale Ave, North York, on M9L 2G9 PHONE NUMBER: (416) 395-2570 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] GRADE RANGE: 6 to 8

Humber Summit Middle School ADDRESS: 60 Pearldale Ave, North York, ON M9L 2G9 PHONE NUMBER: (416) 395-2570 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] GRADE RANGE: 6 to 8 Humber Summit Middle School is located near Finch and Islington. It draws students from a large attendance area, reaching from near Islington and Steeles to Weston and Wilson. Extra Curricular The 540 students Humber Summit serves represent diverse Happenings cultural, racial, and faith backgrounds. Our vision is based on Staff and members of three priorities: Student Achievement, Parent and Community the community offer a Engagement and Financial Stability. We will use the School wide variety of extra Effectiveness Framework as a tool to develop, implement and curricular activities. monitor our progress, based on an analysis of data (EQAO, CASI, Students at Humber DRA and Math Assessment). By using this framework we will be Summit can participate able to implement a more strategic approach, an intentional in athletic, technology, allocation of resources and equity of outcome for all students. leadership and arts based programs: Art Club, Philanthropy Club, Newcomers Homework Club, Student Council, Boy’s Volleyball, Girl’s Partnerships at Work Volleyball, Library Club To build a safe learning environment After School Literacy for all students we have engaged in a and Numeracy, Math partnership with Osgoode Hall Law Club, Sisterhood, Young students who are providing peer Lions Floor Hockey, mediation training to grade 8 Table Tennis Boys and students. We will be having Girls, Entrepreneurial assemblies that focus on the issues Club Choir, School of Adolescent Development, Band, Intramural Cyberbullying and Bullying with Basketball, Boys performances from Miche Mee, Earl LaPierre, Toronto Police Basketball, School Services,Quincy Mac and MADD. -

Appendix D: Violence Reduction Program Update

Item 7 - Chief Operating Officer's Report on Tenant Services and Initiatives TSC Public Meeting - November 24, 2020 Item Report:TSC:2020-43 Page 1 of 9 7 - TSC:2020-43 Appendix D: Violence Reduction Program Update At its meeting of June 27, 2019, the TCHC Board of Directors directed staff - to operationalize the VRP. The last update was provided at the December 5, Appendix 2019 TSC meeting. The VRP is focused on improving safety and security for tenants. It is in response to the disproportionate frequency of violence that occurs on TCHC D property, which is rooted in the levels of poverty, addiction, mental health needs and street-involvement present in the TCHC tenant population. Due to the complex nature of the ten identified high needs communities, the VRP includes enhanced enforcement activity through a dedicated and on- site Community Safety Unit (“CSU”) presence, in collaboration with Toronto Police Service (“TPS”), as well economic development and community and social supports in collaboration with the City of Toronto. The program will be implemented through the regions under the Community Safety and Support Pillar and work with integrated hub teams to support local community safety initiatives. Implementation Status Economic Development and Social Supports The Operations Team, led by the Manager of Community Safety and Support in the Central Region, has worked closely with Social Development, Finance and Administration (“SDFA”) to design a fulsome approach to providing economic development and social support related to community safety. The following actions are underway: • Three Memorandums of Understanding (“MOUs”) were developed and signed by TCHC and SDFA.