Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

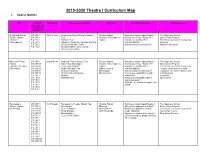

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I. Course Outline Unit Current Timeframe Assessments/Activities Big Idea Essential Questions Core Resources Arkansas SS Framework Alignment Greek and Roman CR.1.TH.1 1st 9 Weeks Greeks and Roman Theatre History Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School Theatre History P.4.THI.2 Test Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character P.4.THI.3 Antigone Test Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Development P.4.THI.5 Napoleon Dynamite Character Analysis characterization? Antigone P.5.THI.2 Life Size Character Poster How do characters affect plot? Napoleon Dynamite P.6.THI.2 Character Observation Journal Greek Theatre Mask Medieval Theatre CR.1.TH.1 2nd 9 Weeks Medieval Theatre History Test Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School History CR.2.THI.1 Solo Acting Monologue Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character Creation CR.2.THI.2 Theme Assessment Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Solo Acting CR.1.THI.3 Modern Morality Play Acting Theories characterization? Veggies Tales used as modern CR.1.THI.4 Character Analysis Monologues How do characters affect plot? (examples of mystery, miracle, and CR.3.THI.1 Character Design Morgue Memorization How do you establish believable morality plays) P.5.THI.1 Audition characters? Everyman P.5.THI.2 Self Reflection How does memorization affect Monologues P.5.THI.4 characterization? P.5.THI.5 -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

Social Welfare in the Greco-Roman World As a Background for Early Christian Practice

Acta Theologica 2016 Suppl 23: 1-28 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v23i1S.1 ISSN 1015-8758 (Print) / ISSN 2309-9089 (Online) © UV/UFS P. Lampe SOCIAL WELFARE IN THE GRECO-ROMAN WORLD AS A BACKGROUND FOR EARLY CHRISTIAN PRACTICE ABSTRACT The essay investigates if and how Greco-Roman theorists attempted to motivate altruistic behaviour and devise a social-welfare ethics. In comparison, it studies actual social-welfare practices on both the private and the state level. Various social-welfare tasks are touched upon – health care; care for the elderly, widows, orphans and invalids; the patron-client system as countermeasure to unemployment; distribution of land, grain, meals and money; alms, donations, foundations as well as education – with hardly any one of them being especially tailored to the poor. The enormous role of civil society – private persons, their households and associations – in holding up social-welfare functions is shown. By contrast, the state was comparatively less involved, the commonwealth of the Romans, especially in Republican times, even less than the Greek city-states. The Greek poleis often invested income such as wealthy citizens’ donations in social welfare, thus brokering between wealthy private donors and less well-to-do persons. The church, living in private household structures during the first centuries, took over the social-welfare tasks of the Greco-Roman household and reviewed them in the light of Hebrew and Hellenistic-Jewish moral traditions. Prof. Peter Lampe, Professor of New Testament Studies, University of Heidelberg, Germany, and Honorary Professor of New Testament, Faculty of Theology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. -

Narcissus the Hunter in the Mosaics of Antioch

Narcissus the Hunter in the Mosaics of Antioch Elizabeth M. Molacek Among the hundreds of mosaic pavements discovered at as the capital of the Hellenistic Seleucid kingdom in 300 BCE Antioch-on-the-Orontes, a total of five represent Narcissus, and remained a thriving city until the Romans took power in the beautiful youth doomed to fall in love with his own 64 BCE. Antioch became the capital of the Roman province reflection. The predominance of this subject is not entirely of Syria; however, it was captured by the Arabs in 637 CE, surprising since it is one of the most popular subjects in bringing an end to almost a thousand years of occupation.2 Roman visual culture. In his catalogue of the mosaics of While its political history is simple to trace from the Hellenis- ancient Antioch, Doro Levi suggests that Narcissus’ frequent tic founding to the Arab sacking, Antioch’s cultural identity appearance should be attributed to his watery reflection due is less transparent. The city was part of the Roman Empire to the fact that Antioch was a “town so proud of its wealth for over five hundred years, but the inhabitants of Antioch of waters, springs, and baths.”1 The youth’s association with did not immediately consider themselves Roman, identifying water may account for his repeated appearance, but the instead with their Hellenistic heritage. As was standard in the present assessment recognizes a Narcissus that is unique to Greek East, the spoken language remained Greek even after Antioch. In art of the Latin West from the first century BCE Rome established control, and many traditions and social onwards, Narcissus has a highly standardized iconography norms were deeply rooted in the Hellenistic culture.3 Antioch that emphasizes his youthful appearance, the act of seeing was a hybrid of both eastern and western influences due to his reflection, and his fate for eternity. -

Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts Leah Zuidema

Language Arts Journal of Michigan Volume 29 Article 9 Issue 2 Location, Location, Location 4-2014 Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts Leah Zuidema Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/lajm Recommended Citation Zuidema, Leah (2014) "Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts," Language Arts Journal of Michigan: Vol. 29: Iss. 2, Article 9. Available at: https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.2013 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Language Arts Journal of Michigan by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRACTICE Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts LEAH A. ZUIDEMA ne of the greatest challenges that could help them in visualizing the taken place in somewhat crowded class- of teaching plays in English action of the play. This is problematic, rooms, typically with about 35 students Olanguage arts courses is the as the cognitive work of visualization per section and little room to move fact that scripts are intended for the is a stepping stone to comprehension: about. The lesson sequence continues stage, not the page. While the plots, practiced readers use visualization to to evolve each year with small changes themes, and dialogue of the best scripts help them understand, make connec- and additions, often inspired by stu- are ripe for intensive literary study, care- tions with, and interpret literary texts dents’ suggestions about “what else” we ful attention to dramatic elements— (Wilhelm, 2008). -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

Greek Dramatic Monuments from the Athenian Agora and Pnyx

GREEK DRAMATIC MONUMENTS FROM THE ATHENIAN AGORA AND PNYX (PLATES 65-68) T HE excavations of the Athenian Agora and of the Pnyx have produced objects dating from the early fifth century B.C. to the fifth century after Christ which can be termed dramatic monuments because they represent actors, chorusmen, and masks of tragedy, satyr play and comedy. The purpose of the present article is to interpret the earlier part of this series from the point of view of the history of Greek drama and to compare the pieces with other monuments, particularly those which can be satisfactorily dated.' The importance of this Agora material lies in two facts: first, the vast majority of it is Athenian; second, much of it is dated by the context in which it was found. Classical tragedy and satyr play, Hellenistic tragedy and satyr play, Old, Middle and New Comedy will be treated separately. The transition from Classical to Hellenistic in tragedy or comedy is of particular interest, and the lower limit has been set in the second century B.C. by which time the transition has been completed. The monuments are listed in a catalogue at the end. TRAGEDY AND SATYR PLAY CLASSICAL: A 1-A5 HELLENISTIC: A6-A12 One of the earliest, if not the earliest, representations of Greek tragedy is found on the fragmentary Attic oinochoe (A 1; P1. 65) dated about 470 and painted by an artist closely related to Hermonax. Little can be added to Miss Talcott's interpre- tation. The order of the fragments is A, B, C as given in Figure 1 of Miss T'alcott's article. -

Stage Manager & Assistant Stage Manager Handbook

SM & ASM HANDBOOK Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre STAGE MANAGER & ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER HANDBOOK December 12, 2008 Proposed changes and updates to the Producer Handbook can be submitted in writing or by email to the General Manager. The General Manager and Active Production Chair will enter all approved changes. VTG SM HANDBOOK: December 12, 2008 1 SM & ASM HANDBOOK Stage Manager & Assistant SM Handbook CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. AUDITIONS a) Pre-Audition b) Auditions and Callbacks c) Post Auditions / Pre First Rehearsal 3. REHEARSALS a) Read Through / First Rehearsal b) Subsequent Rehearsals c) Moving to the Mainstage 4. TECH WEEK AND WEEKEND 5. PERFORMANCES a) The Run b) Closing and Strike 6. SM TOOLS & TEMPLATES 1. Scene Breakdown Chart 2. Rehearsal Schedule 3. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Guidelines for Stage Management 4. The Prompt Book VTG SM HB: December 12, 2008 2 SM & ASM HANDBOOK 5. Production Technical Requirements 6. Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 7. Rehearsal Attendance Sheet 8. Stage Management Kit 9. Sample Blocking Notes 10. Rehearsal Report 11. Sample SM Production bulletins 12. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals on Mainstage – SM Guidelines 13. Rehearsals on the Mainstage – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 14. Sample Preset & Scene Change Schedule 15. Performance Attendance Sheet 16. Stage Crew Guidelines and Information Sheet 17. Sample Prompt Book Cues 18. Use of Theatre during Performances – SM Guidelines 19. Sample Production Information Sheet for FOH & Bar 20. Sample SM Preshow Checklist 21. Sample SM Intermission Checklist 22. SM Post Show Checklist 23. -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

'Techné' and 'Paideia'

Acta Scientiarum http://www.uem.br/acta ISSN printed: 2178-5198 ISSN on-line: 2178-5201 Doi: 10.4025/actascieduc.v38i3.28713 The rapports between ‘techné’ and ‘paideia’ in the Roman Empire: reading the Antiochene mosaics Gilvan Ventura da Silva Departamento de História, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Av. Fernando Ferrari, 514, 29075-910, Vitória, Espírito Santo, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Discussion on the Roman mosaic as techné or as ars, is provided, or rather, a decoration technique for interiors made at high specialization levels. When the main procedures adopted in mosaic art are established, we will show how a certain technique, a particular way in handling unsophisticated materials learnt by semi-illiterate people, lost throughout the ages, was used to express themes and motifs connected with paideia, the superior education of the Greco-Roman elite. As a case study, two mid-3rd century CE mosaics found in the so-called House of Menander, a villa located in the suburb of Daphne, in southern Antioch, will be investigated. Keywords: late antiquity, paideia, image. Artes do fazer e usos do saber no império romano: ‘lendo’ os mosaicos de Antioquia RESUMO. Neste artigo, pretendemos desenvolver algumas reflexões acerca do mosaico romano como techné ou ars, ou seja, como uma técnica de decoração de interiores que comportava um alto nível de especialização. Uma vez estabelecidos, em linhas gerais, os procedimentos empregados na confecção dos mosaicos, buscaremos, em seguida, demonstrar como determinada técnica, uma maneira particular de manipulação de materiais rústicos dominada por indivíduos semiletrados cuja memória praticamente se perdeu, é mobilizada com a finalidade de exprimir temas e motivos conectados com a paideia, a formação cultural superior concedida aos membros da elite greco-romana. -

Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity: a Sourcebook/Wendy Cotter

MIRACLES IN GRECO-ROMAN ANTIQUITY Miracles in Greco-Roman Antiquity is a sourcebook which presents a concise selection of key miracle stories from the Greco- Roman world, together with contextualizing texts from ancient authors as well as footnotes and commentary by the author herself. The sourcebook is organized into four parts that deal with the main miracle story types and magic: Gods and Heroes who Heal and Raise the Dead, Exorcists and Exorcisms, Gods and Heroes who Control Nature, and Magic and Miracle. Two appendixes add richness to the contextualization of the collection: Diseases and Doctors features ancient authors’ medical diagnoses, prognoses and treatments for the most common diseases cured in healing miracles; Jesus, Torah and Miracles selects pertinent texts from the Old Testament and Mishnah necessary for the understanding of certain Jesus miracles. This collection of texts not only provides evidence of the types of miracle stories most popular in the Greco-Roman world, but even more importantly assists in their interpretation. The contextualizing texts enable the student to reconstruct a set of meanings available to the ordinary Greco-Roman, and to study and compare the forms of miracle narrative across the whole spectrum of antique culture. Wendy Cotter C.S.J. is Associate Professor of Scripture at Loyola University, Chicago. MIRACLES IN GRECO-ROMAN ANTIQUITY A sourcebook Wendy Cotter, C.S.J. First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

New Directions for Kabuki Performances in America in the 21St Century

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 4-2-2019 New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21st Century Narumi Iwasaki Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Iwasaki, Narumi, "New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21st Century" (2019). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4942. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6818 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21 st Century by Narumi Iwasaki A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Japanese Thesis Committee: Laurence Kominz, Chair Suwako Watanabe Jon Holt Portland State University 2019 ©2019 Narumi Iwasaki i Abstract Transitions from the first kabuki performance abroad in Russia in 1928 to the recent performances around the world show various changes in the purpose and production of kabuki performances overseas. Kabuki has been performed as a Japanese traditional art in the U.S. for about 60 years, and the United States has seen more kabuki than any other country outside of Japan. Those tours were closely tied to national cultural policy of both Japan and the USA in the early years (Thornbury 2–3).