Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander It is a truth universally acknowledged that the plays of Menander owe a great debt to Classical Athenian drama: connections between plays such as Aristophanes’ Cocalus and Menander were noted in didascalia, and similarly the thematic and structural similarities between New Comedy and the works of Euripides were already recognized in Hellenistic scholarship (Arnott 1972; Csapo 2000; Hunter 2011). Sophocles, on the other hand, is rarely included in this discussion of dramatic influence, more often regarded solely for his role as the pinnacle of tragic poets. It is the purpose of this paper to reanalyze possible connections between the corpus of Sophocles and that of Menander by examining both the Antigone and the Dyscolus as plays employing one of the most familiar stock characters of ancient comedy: the “blocking” father figure. This father figure—whose earliest incarnation arguably belongs to Old Comedy, such as Strepsiades from Clouds—is perhaps best known for his characterization in the plays of Greek New Comedy and their later, Latin iterations. Generally an old and intransigent father, the “blocking” figure is generically defined by his interference in the life of his young offspring; in New Comedy, this interference takes the form of intervention in the budding romance of two young lovers, whose inconvenient marriage will inevitably bring about the typical finale. This character, at first glance, may appear to be a creature created solely for light-hearted drama. Creon of the Antigone, however, whose stubborn and belligerent character has been carefully surveyed for his role within the tragedy itself (see Roisman 1996), additionally shares many features with the father of Menander’s only intact play, Knemon of the Dyscolus. -

The Roles of Solon in Plato's Dialogues

The Roles of Solon in Plato’s Dialogues Dissertation Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Samuel Ortencio Flores, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Bruce Heiden, Advisor Anthony Kaldellis Richard Fletcher Greg Anderson Copyrighy by Samuel Ortencio Flores 2013 Abstract This dissertation is a study of Plato’s use and adaptation of an earlier model and tradition of wisdom based on the thought and legacy of the sixth-century archon, legislator, and poet Solon. Solon is cited and/or quoted thirty-four times in Plato’s dialogues, and alluded to many more times. My study shows that these references and allusions have deeper meaning when contextualized within the reception of Solon in the classical period. For Plato, Solon is a rhetorically powerful figure in advancing the relatively new practice of philosophy in Athens. While Solon himself did not adequately establish justice in the city, his legacy provided a model upon which Platonic philosophy could improve. Chapter One surveys the passing references to Solon in the dialogues as an introduction to my chapters on the dialogues in which Solon is a very prominent figure, Timaeus- Critias, Republic, and Laws. Chapter Two examines Critias’ use of his ancestor Solon to establish his own philosophic credentials. Chapter Three suggests that Socrates re- appropriates the aims and themes of Solon’s political poetry for Socratic philosophy. Chapter Four suggests that Solon provides a legislative model which Plato reconstructs in the Laws for the philosopher to supplant the role of legislator in Greek thought. -

The Ostensible Author of Ps.-Aeschines Letter 10 Reconsidered

Journal of Hellenic Studies 139 (2019) 210–221 doi:10.1017/S0075426919000703 © The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies 2019 THE OSTENSIBLE AUTHOR OF PS.-AESCHINES LETTER 10 RECONSIDERED ZILONG GUO Northeast Normal University* Abstract: This article examines the alleged author, or first-person narrator, of the tenth pseudonymous letter in the Corpus Aeschineum. It argues that the forger, in a short epistolary novel that describes the seduction of a certain Callirhoe in Troy, uses puns (αἰσχύνειν, ἀναισχυντία, etc.) on the name of the fourth-century BC orator Aeschines. It notes that αἰσχρός-words recur in ancient works and, as a rhetorical device, are attested in Demosthenes. The forger’s aims are, first, to serialize the ‘Aeschinean’ letters as a whole by relating them to the same author and, second, to create an ‘aischro- logic’ counterpart of the Callirhoe, which is attributed to Chariton (Χαρίτων/‘The Graceful’). Thus there is less likelihood of suggesting other figures such as the eponymous Aeschines Socraticus. Keywords: pseudonymous letters, authorship, Aeschines, Chariton, pun In the manuscript tradition of Aeschines we find a collection of 12 letters that purport to describe the orator’s exile from Athens after the ‘crown trial’ in 330 BC. These letters are called ‘pseudony- mous’ because of their questionable authenticity: Letters 2, 3, 7, 11 and 12 imitate the letters of Demosthenes and are reminiscent of the historical declamations and progymnasmata familiar from Hellenistic times onward; Letters 1, 5, 6, 8, 9 and 10 reconstruct a fictitious narrative of Aeschines’ exile, and have traditionally been accepted as products of the so-called Second Sophistic. -

Goneis in Athenian Law (And Perception)

GONEIS IN ATHENIAN LAW (AND PERCEPTION) David Whitehead Queen’s University Belfast [email protected] Abstract: This paper aims to establish what the laws of classical Athens meant when they used the term goneis. A longstanding and widespread orthodoxy holds that, despite the simple and largely unproblematic “dictionary” definition of the noun goneus/goneis as parent/parents, Athenian law extended it beyond an individual’s father and mother, so as to include – if they were still alive – protection and respect for his or her grandparents, and even great-grandparents. While this is not a notion of self-evident absurdity, I challenge it on two associated counts, one broad and one narrow. On a general, contextual level, genre-by genre survey and analysis of the evidence for what goneus means (and implies) in everyday life and usage shows, in respect of the word itself, an irresistible thrust in favour of the literal ‘parent’ sense. Why then think otherwise? Because of confusion, in modern minds, engendered by Plato and by Isaeus. In Plato’s case, his legislation for Magnesia contemplates (I argue) legal protection for grandparents but does not, by that mere fact, extend the denotation of goneis to them. And crucially for a proper understanding of the law(s) of Athens itself, two much-cited passages in the lawcourt speeches of Isaeus, 1.39 and 8.32, turn out to be the sole foundation for the modern misunderstanding about the legal scope of goneis. They should be recognised for what they are: passages where law is secondary and rhetorical persuasion paramount. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Archaic Eretria

ARCHAIC ERETRIA This book presents for the first time a history of Eretria during the Archaic Era, the city’s most notable period of political importance. Keith Walker examines all the major elements of the city’s success. One of the key factors explored is Eretria’s role as a pioneer coloniser in both the Levant and the West— its early Aegean ‘island empire’ anticipates that of Athens by more than a century, and Eretrian shipping and trade was similarly widespread. We are shown how the strength of the navy conferred thalassocratic status on the city between 506 and 490 BC, and that the importance of its rowers (Eretria means ‘the rowing city’) probably explains the appearance of its democratic constitution. Walker dates this to the last decade of the sixth century; given the presence of Athenian political exiles there, this may well have provided a model for the later reforms of Kleisthenes in Athens. Eretria’s major, indeed dominant, role in the events of central Greece in the last half of the sixth century, and in the events of the Ionian Revolt to 490, is clearly demonstrated, and the tyranny of Diagoras (c. 538–509), perhaps the golden age of the city, is fully examined. Full documentation of literary, epigraphic and archaeological sources (most of which have previously been inaccessible to an English-speaking audience) is provided, creating a fascinating history and a valuable resource for the Greek historian. Keith Walker is a Research Associate in the Department of Classics, History and Religion at the University of New England, Armidale, Australia. -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

Menander: Personal Address and Addressing the Audience

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UTokyo Repository Menander: Personal Address and Addressing the Audience journal or 東京大学西洋古典学研究室紀要 publication title volume 8 page range 103-133 year 2013-12 URL http://doi.org/10.15083/00078898 Menander: Personal Address and Addressing the Audience*1 Adele C. Scafuro 1 Introduction Studies of personal address have become increasingly visible in the field of Classics as a part of the larger methodological camp of Discourse Anal- ysis. Classical scholars have long paid attention to personal address in Menander, even if, as we shall soon see, Menander is rather sparing in his use of it. Sandbach and Gomme, for example, were particularly sensitive to its nuanced appearances in their grand commentary published in 1973. This is evident, for example, in their comments on Act IV of Epitrepontes. At this point in the play (at lines 853-877), Pamphile is already onstage after a heart-rending discussion with her father; he wants her to divorce her husband Charisios. Unbeknownst to her father, Pamphile had been raped before she married (this happened before the play began); she had *1 I am grateful to Prof. Y. Kasai for arranging my visit and the occasion for the pre- sentation of this (now revised) paper at the University of Tokyo in March 2013; I am also grateful to the audience for its attentive responses, and especially to Profs. M. Kubo and M. Sakurai for their observations. Further thanks are due Oxford Univer- sity Press for permission to repeat and expand, in sections 3 and 4 of this essay, a portion of chapter 10 ‘Menander’ (pp.218-38) in The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Comedy, eds. -

The Motif of Love in Euripides' Works Helen and Medea

THE MOTIF OF LOVE IN THE HELEN AND THE ALCESTIS OF EURIPIDES by Eleftheria N. Athanasopoulou DOCTORAL DISSERTATION submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR LITTERARUM ET PHILOSOPHIAE in GREEK in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR J. L. P. WOLMARANS JANUARY 2008 For my family, and especially for my children… «Αν κάποιος προηγείται απλώς του καιρού του, κάποια μέρα ο καιρός θα τον προλάβει». (Wittgenstein, L. 1986). «Η θάλασσα που μας πίκρανε είναι βαθιά κι ανεξερεύνητη και ξεδιπλώνει μιαν απέραντη γαλήνη». (Seferis, G. 1967). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is hereby made to Prof. J. L. P. Wolmarans for his advice, patience and assistance. This work would not have been completed without his encouragement. Indeed, his criticism was beneficial to the development of my ideas. It is of special significance to acknowledge the support given to me by some friends. I am particularly indebted to them for various favours. I also thank my husband for his advice, so that I could look afresh at a large number of questions. I wish to thank the anonymous reader for the improvements (s)he suggested. Johannesburg 2008 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABSTRACT xiii ΠΕΡΙΛΗΨΗ xi I. INTRODUCTION The Helen and the Alcestis 1 Rationale 3 Problem Statement 5 Methodology 6 Layout and Structure 8 Overview of Literature 12 Note to the Reader 14 II. THE PHILOSOPHY OF EURIPIDES AND WITTGENSTEIN Euripides’ Profile: Life and Works 15 Wittgenstein’s Profile: Life and Works 23 Euripides and Wittgenstein: Parallel Patterns of Thought 33 The Motif of Love, Language and Gloss analysis 37 III. -

Thalheim's Isaeus Itaei Orationes Cum Deperditarum Fragmentis Post Carolum Scheibe Iterum Edidit Th

The Classical Review http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR Additional services for The Classical Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Thalheim's Isaeus Itaei orationes cum deperditarum fragmentis post Carolum Scheibe iterum edidit Th. Thalheim. Leipzig: Teubner. Mk. 2. 40. W. Wyse The Classical Review / Volume 18 / Issue 02 / March 1904, pp 115 - 120 DOI: 10.1017/S0009840X0020944X, Published online: 27 October 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009840X0020944X How to cite this article: W. Wyse (1904). The Classical Review, 18, pp 115-120 doi:10.1017/S0009840X0020944X Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAR, IP address: 130.132.123.28 on 13 Jul 2015 THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. 115 O.P.5 with the variant diuitum (-is O), and word ' emendare' which is used invariably is given as a variant in P.2'7: militum is the in the subscriptiones, is to be construed in reading of Rat.2 and a variant in P.10. 313 its most literal sense; and that view is, I furens: with Or. Boul. W. M. Rh. D.1 P.5 think, fully borne out by this MS. The (uel fremens) P,7: it is also given as a changes of the original text amount to variant in P.10 Lo.2 Z. 314 et: I noted this nothing more than insertions of omitted also from 0. Or. H. Trin. P.8 328 lines or words, and corrections of slips of retudit; so too O. and Or. (uel retundit). -

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece

Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Ancient Greek Philosophy but didn’t Know Who to Ask Edited by Patricia F. O’Grady MEET THE PHILOSOPHERS OF ANCIENT GREECE Dedicated to the memory of Panagiotis, a humble man, who found pleasure when reading about the philosophers of Ancient Greece Meet the Philosophers of Ancient Greece Everything you always wanted to know about Ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask Edited by PATRICIA F. O’GRADY Flinders University of South Australia © Patricia F. O’Grady 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Patricia F. O’Grady has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi.ed as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Suite 420 Union Road 101 Cherry Street Farnham Burlington Surrey, GU9 7PT VT 05401-4405 England USA Ashgate website: http://www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask 1. Philosophy, Ancient 2. Philosophers – Greece 3. Greece – Intellectual life – To 146 B.C. I. O’Grady, Patricia F. 180 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Meet the philosophers of ancient Greece: everything you always wanted to know about ancient Greek philosophy but didn’t know who to ask / Patricia F. -

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

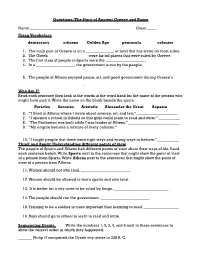

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens.