Menander: Personal Address and Addressing the Audience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem. -

Aristotle and Menander on the Ethics of Understanding

Aristotle and Menander on the Ethics of Understanding Submitted by Valeria Cinaglia to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics In January 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: 1 ABSTRACT This doctoral thesis explores a subject falling in the interface between ancient Greek philosophy and literature. Specifically, I am concerned with common ground between the New Comedy of Menander and aspects of Aristotle’s philosophy. The thesis does not argue that the resemblance identified between the two writers shows the direct influence of Aristotle on Menander but rather thay they share a common thought-world. The thesis is structured around a series of parallel readings of Menander and Aristotle; key relevant texts are Menander’s Epitrepontes , Samia , Aspis , Perikeiromene and Dyscolos and Aristotle’s Posterior Analytics , Nicomachean and Eudemian Ethics , De Anima and Poetics . My claim is that Menander’s construction of characters and plots and Aristotle’s philosophical analyses express analogous approaches on the subject of the relationship between knowledge and ethics. Central for my argument is the consideration that in Aristotle’s writings on ethics, logic, and psychology, we can identify a specific set of ideas about the interconnection between knowledge-formation and character or emotion, which shows, for instance, how ethical failings typically depend on a combination of cognitive mistakes and emotional lapses. -

Loeb Classical Library

LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY 2015 Founded by JAMES LOEB 1911 Edited by JEFFREY HENDERSON DIGITAL LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY For information about digital Loeb Classical Library access plans or to register for an institutional free trial, visit www.loebclassics.com Winner, PROSE Award for Best Humanities eProduct, Association of American Publishers “For the last couple of decades, the Loeb Library has been undergoing a renaissance. There are new or revised translations of many authors, and, a month or two back, the entire library was brought online at loebclassics.com. There are other searchable classics databases … Yet there is still something glorious about having all 500-plus Loebs online … It’s an extraordinary resource.” —ROGER KIMBALL, NEW CRITERION “The Loeb Library … remains to this day the Anglophone world’s most readily accessible collection of classical masterpieces … Now, with their digitization, [the translations] have crossed yet another frontier.” —WALL STREET JOURNAL The mission of the Loeb Classical Library, founded by James Loeb in 1911, has always been to make Classical Greek and Latin literature accessible to the broadest range of readers. The digital Loeb Classical Library extends this mission into the twenty-first century. Harvard University Press is honored to renew James Loeb’s vision of accessibility and to present an interconnected, fully searchable, perpetually growing, virtual library of all that is important in Greek and Latin literature. e Single- and dual-language reading modes e Sophisticated Bookmarking and Annotation features e Tools for sharing Bookmarks and Annotations e User account and My Loeb content saved in perpetuity e Greek keyboard e Intuitive Search and Browse e Includes every Loeb volume in print e New volumes uploaded regularly www.loebclassics.com also available in theNEW i tatti TITLES renaissance library THEOCRITUS. -

Menander's Characters in the Fourth Century BC and Their Reception in Modern Greek Theatre

Menandrean Characters in Context: Menander’s Characters in the fourth century BC and their reception in Modern Greek Theatre. Stavroula Kiritsi Royal Holloway, University of London PhD in Classics 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Stavroula Kiritsi, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______Stavroula Kiritsi________________ Date: _________27/06/2017_______________ 2 Abstract The thesis explores the way in which character is represented in Menander’s comedies and in the revival, translation, and reception of Menandrean comedy in the modern Greek theatre. Although modern translators and directors may have sought to reproduce the ancient dramas faithfully, they inevitably reshaped and reinterpreted them to conform to audience expectations and the new cultural context. Comparing aspects of character in the ancient and modern plays sheds light on both traditions. In assessing how character was conceived in the Hellenistic period, I make use of ethical works by Aristotle and other philosophers, which provide an appropriate vocabulary for identifying the assumptions of Menander and his audience. For the modern adaptations, I have made extensive use of a variety of archival materials as well as interviews with artists engaged at every stage of the production. The thesis comprises an Introduction, two Parts (I-II), and Conclusion. Part I examines Menandrean characters in the context of the Hellenistic Greek audience and society, with special reference to Aristotle’s and Theophrastus’ accounts of character and emotion. In the first chapter of Part II I survey the ‘loss and survival’ of Menander from antiquity and Hellenistic times, through Byzantium and the post-Byzantine period, to nineteenth-century Greece. -

Gendered Recognitions in Menander's Sikyonioi

Gendered Recognitions in Menander’s Sikyonioi New Comedy’s “recognition plot” is its most common: children lost or exposed are iden- tified by tokens revealing their parentage. The recognition, anagnorisis, restores the child to citizen society (Lape 2010, Munteanu 2002). In Menander’s plays, recognition reunites the fami- ly, the dramatic goal. Furley (2014: 107) suggests that the recognition plot symbolized the self- development and recognition of inner character. But character development and self-understanding in Menander are reserved for male characters: female characters show resolve, but remain largely invisible and do not experience development or maturity. Reconciliations too occur largely between men: husbands and wives find peace after crisis (Epitrepontes, Heros), but emotional union occurs between men (Samia, Perikeiromene, Misoumenos, Dsykolos; Heap 1998). The recognition plot is thus gendered— most observably, I argue, in Sikyonioi. Male recognitions occur in Epitrepontes and Hiereia, female in Misomenos and Phasma, Heros, Georgos, and Perikeiromene feature double recogni- tions of brother and sister. Sikyonioi is the only play that shows recognitions of an unrelated man and woman in the same play. Scholars (Arnott 2000; Belardinelli 1994; Kassel 1965) have pieced the plot together. Two unrelated children were lost: Stratophanes given away by his Athenian parents for unknown reasons, Philoumene kidnapped and sold to Stratophanes’ adoptive family. Grown up, Stratopha- nes brings Philoumene to Athens. Neighbor boy Moschion, an Athenian, hopes to possess Philoumene. Stratophanes discovers he is an Athenian citizen (Moschion’s older brother), and when Philoumene’s father is found, they may marry. Philoumene’s status creates tension in the men around her and provides the impetus for the play’s action (Traill 2008). -

The Good, the Bad, and the Grouch a Comparison of Characterization in Menander and Ancient Philosophers by Matthew W. Mcdonald

The Good, the Bad, and the Grouch A Comparison of Characterization in Menander and Ancient Philosophers By Matthew W. McDonald ἁλωτα γίνετ’ ἐπιμελείᾳ καὶ πόνῳ ἅπαντ’ “All is attainable through care and work” -Sostratos, Dyskolos 862-3 Thanks to my father and mother, Dr. William Owens, Dr. Ruth Palmer, Dean Webster, Cary Frith, and all the faculty and staff members of the Department of Classics and World Religions and of the Honors Tutorial College ii Table of Contents: Forward: My History with the Texts iv Chapter 1: Introduction The Background of Menander 1 The Study of Characterization 7 Characterization in Philosophy 16 Chapter 2: Character through Solitude and Friendship: An Analysis of the Dyskolos The Dyskolos in History and Scholarship 30 The Characters of Knemon, Kallippides, Sostratos, and Gorgias 40 Chapter 3: Character through Father and Son: An Analysis of the Samia The Samia in History and Scholarship 61 The Characters of Moschion and Demeas 69 Chapter 4: Conclusion 100 Bibliography 106 iii Forward: My History with the Texts I was first introduced to Menander in the tenth grade, when I played Sostratos in my school’s production of the Dyskolos. It is difficult to explain why exactly I became so fond of that play, I think most of my classmates found it boring; it was by no means gut-bustingly hilarious, nor was the plot particularly interesting. Yet, the characters had a certain undeniable charm; the lover was endearingly naïve; the country-boy was unexpectedly profound; the slaves were deviously clever; and the titular grumpy old man embodied the sympathetic villain. -

Menander's Sikyonioi

Gendered Differences in the Recognition Plot: Menander’s Sikyonioi SERENA S. WITZKE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [email protected] Introduction Since its rediscovery in 1901, with additional fragments found and then published in the 1960s1, Sikyonioi has intrigued New Comedy scholars2. Despite frustrating lacunae, the plot of this double recognition comedy has been painstakingly pieced together: a young woman (kidnap- ped at an early age) finds her father, while a mercenary soldier also dis- covers his natal family and new role as an Athenian citizen; they marry3. This widely accepted reconstruction has prompted questions about the way Menander develops his recognition plot; the implications of gender in his identity plays; and the use of the surface-level recognition plot to symbolize internal character development. 1 — See Gomme and Sandbach (1973: 632) and Arnott (2000: 193-195) on discovery of the Sikyonioi manuscripts and Handley (2011) and Blanchard (2014) on the rediscovery of Menander in general. 2 — On title Sikyonioi vs. Sikionios, see Arnott (1997a: 1-3; 2000: 196-97), Gomme and Sandbach (1973: 632-33), and R. Kassel (1965). I follow Arnott in the use of Sikyonioi. 3 — Arnott (1997abc, 2000); Belardinelli (1994); Blanchard & Bataille (1965); Gomme & Sandbach (1973); Handley (1965); Kassel (1965); Lloyd-Jones (1966); Merkelbach (1966). EuGeStA - n°6 - 2016 42 SERENA S. WITZKE I argue here that the design of the plot of Sikyonioi reveals the gen- dering of anagnorisis through the play’s unique man-woman double recognition. Menander’s surface-level recognitions (the literal discovery of natal identity) are symbolic of the inner development of the recognized characters4, but I suggest that while the recognition plot allows men to discover natal identity and pushes them toward character development, the recognition of a woman puts an end to her dramatic journey imme- diately. -

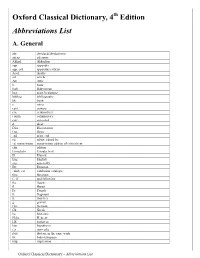

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

New Perspectives on Postclassical Comedy

New Perspectives on Postclassical Comedy Pierides Studies in Greek and Latin Literature Series Editors: Philip Hardie and Stratis Kyriakidis Volume I: S. Kyriakidis, Catalogues of Proper Names in Latin Epic Poetry: Lucretius - Virgil - Ovid Pierides Studies in Greek and Latin Literature Volume II: New Perspectives on Postclassical Comedy Edited by Antonis K. Petrides and Sophia Papaioannou New Perspectives on Postclassical Comedy, Edited by Antonis K. Petrides and Sophia Papaioannou This book first published 2010 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2010 by Antonis K. Petrides and Sophia Papaioannou and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2411-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2411-8 In grateful memory of Colin François Lloyd Austin (1941-2010) The great use of life is to spend it for something that will outlast it (William James) TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................... ix CONTRIBUTORS ........................................................................................... xi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ -

Menander's Samia: a New Translation

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2006 Menander's Samia: A New Translation Seth A. Jeppesen Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the History Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jeppesen, Seth A., "Menander's Samia: A New Translation" (2006). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 709. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/709 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MENANDER'S SAMIA: A NEW TRANSLATION by Seth A. Jeppesen Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DEPARTMENT HONORS in History Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Department Honors Advisor Dr. Mark L. Damen Dr. Susan 0 . Shapiro Director of Honors Program Dr. Christie Fox UT AH ST A TE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT 2006 Menander's Samia .9L9'.[f,w 'Translation 69 Setli.9L Jeppesen Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................... i Introduction ................................................... .. .................... ii Menader's Samia ................................................................... 1 Notes ... .... .... ..... ............ .................................................... -

Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy

Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy The Hellenistic Age • general chaos and confusion after Sparta’s victory in the Peloponnesian War • led to a civil war of sorts inside Greece • the rise of Thebes • the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE): “the graveyard of the Spartan aristocracy” Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy The Hellenistic Age • the rise of Macedon • especially, Philip II • defeated the combined forces of the southern Greeks at Chaeronea (338 BCE) • but Philip was assassinated (336 BCE) • and Alexander assumed Philip’s throne, saddled up and rode east Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy The Hellenistic Age • Alexander’s conquests opened up the East to Greek cultural colonization • the Greek language began to evolve into a vernacular dialect called koine • the Greeks were, in general, richer than ever before – but depressed – and disoriented (get it?) Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy Philosophy in the Hellenistic Age • rise of many new philosophies • Stoicism: be unemotional and trust that the universe has a plan • Epicureanism: retreat behind garden walls and avoid pain Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy Art in the Hellenistic Age • all this led to drastic changes in art • e.g. statuary focuses on violence/pain • technically brilliant but hollow Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy Post-Classical Drama • tragedy faltered, collapsed and died – though revivals of “old” tragedies from the Classical Age still had a huge following • comedy survived by inventing the sit-com • also, mime thrived but did not peak — yet! – still too bawdy and low-brow for most viewers – drama would not sink as low as mime— at least, for a while Chapter 10: Later Greek Comedy Post-Classical Drama • according to Platonius, funding for drama was undercut, leading to cost-cutting measures – e.g. -

Constructing Aischunē in Menander's Samia And

STAGING SHAME: CONSTRUCTING AISCHUNĒ IN MENANDER’S SAMIA AND DYSKOLOS by Daniel M Ruprecht ____________________________ Copyright © Daniel M Ruprecht 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND CLASSICS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS WITH A MAJOR IN CLASSICS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 Ruprecht 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: How Do We Feel? ................................................................................................. 8 Emotion Theory ........................................................................................................................ 8 Modern Shame, Guilt, and Embarrassment ........................................................................ 13 aischunē and aidōs................................................................................................................... 21 CHAPTER 2: aischunē in Samia ............................................................................................... 23 CHAPTER 3: aischunē in Dyskolos .......................................................................................... 44 CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................................................