Feminist Revisionary Histories of Rhetoric: Aspasia's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Interpreter Zero: the Irony of Themistocles

Looking for Interpreter Zero: The Irony of Themistocles Themistocles and his historians reflect a range of attitudes to language, identity and loyalty, giving us a sense of attitudes towards interpreters far back in time and memory. Christine ADAMS. Published: March 1, 2019 Last updated: March 1, 2019 Themistocles was a rare example of a Greek who could speak a foreign language …[1] This sense of a common tongue was the decisive criterion for determining who were Greeks [2] Herodotus (484-425 BCE) tells the story of the cradle of western civilisation in The Histories of the Persian Wars, relating the stories of the Greeks and their neighbours - those they called Barbarians - and giving detailed information about the peoples of the Mediterranean as well as the lead up to the wars, before giving an account of the wars themselves. “By combining oral accounts of the past with his own observation of surviving monuments, natural phenomena and local customs, he produced a prose narrative of unprecedented length, intellectual depth and explanatory power.”[3] Histories shows an awareness of the need for language intermediaries, drawing a distinction between linguists and the ‘interpreters’ of dreams or oracular pronouncements and citing instances of interpreters at work. There were Greek-speaking communities in Egypt, for instance. The Pharaoh Psammetichus had allowed them to settle and had honoured all of his commitments to them. He had even “intrusted to their care certain Egyptian children whom they were to teach the language of the Greeks. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Katy Shannahan Edited

1 Katy Shannahan OUHJ 2013 Submission The Impact of Failed Lesbian Feminist Ideology and Rhetoric Lesbian feminism was a radical feminist separatist movement that developed during the early 1970s with the advent of the second wave of feminism. The politics of this movement called for feminist women to extract themselves from the oppressive system of male supremacy by means of severing all personal and economic relationships with men. Unlike other feminist separatist movements, the politics of lesbian feminism are unique in that their arguments for separatism are linked fundamentally to lesbian identification. Lesbian feminist theory intended to represent the most radical form of the idea that the personal is political by conceptualizing lesbianism as a political choice open to all women.1 At the heart of this solution was a fundamental critique of the institution of heterosexuality as a mechanism for maintaining masculine power. In choosing lesbianism, lesbian feminists asserted that a woman was able to both extricate herself entirely from the system of male supremacy and to fundamentally challenge the patriarchal organization of society.2 In this way they privileged lesbianism as the ultimate expression of feminist political identity because it served as a means of avoiding any personal collaboration with men, who were analyzed as solely male oppressors within the lesbian feminist framework. Political lesbianism as an organized movement within the larger history of mainstream feminism was somewhat short lived, although within its limited lifetime it did produce a large body of impassioned rhetoric to achieve a significant theoretical 1 Radicalesbians, “The Woman-Identified Woman,” (1971). 2 Charlotte Bunch, “Lesbians In Revolt,” The Furies (1972): 8. -

A Feminist Conversation

#1 Feminist Reflections NOV. 2018 his essay is the outcome of a conversation between two radical African feminists, TPatricia McFadden and Patricia Twasiima, who unapologetically and with sheer pleasure, think, live and share feminist ideas and imaginaries. Both are part of the African Feminist Refection and Action Group.They live in eastern and southern Africa, respectively, and whilst A FEMINIST CONVERSATION: they are ‘separated’ by distance and age in very conventional ways, their ideas and passions for freedom and being able to live lives of dignity Situating our radical ideas and through their own truths as Black women on their continent, and beyond, are the ties that bind them inseparably as Contemporary African energies in the contemporary Feminists in the 21st century. The conversation they are engaged with and African context in ranges over several core challenges and tasks that have faced feminists ever since the emergence of a public radical women’s politics of resistance against patriarchy. But it also refects Patricia McFadden on new faces of patriarchy and oppression we are confronted with today and on how women`s Patricia Twasiima struggles to counter them can be strengthened. A FEMINIST CONVERSATION: Situating our radical ideas and energies in the contemporary African context women generated a nationalist discourse that Contextualizing the Conversation legitimized their case. Nationalists and fem- omen have resisted oppression and ex- inists collaborated to pursue their common clusion for as long as humans have lived goal -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

Antifeminism Online. MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way)

Antifeminism Online MGTOW (Men Going Their Own Way) Jie Liang Lin INTRODUCTION Reactionary politics encompass various ideological strands within the online antifeminist community. In the mass media, events such as the 2014 Isla Vista killings1 or #gamergate,2 have brought more visibility to the phenomenon. Although antifeminism online is most commonly associated with middle- class white males, the community extends as far as female students and professionals. It is associated with terms such as: “Men’s Rights Movement” (MRM),3 “Meninism,”4 the “Red Pill,”5 the “Pick-Up Artist” (PUA),6 #gamergate, and “Men Going Their Own Way” (MGTOW)—the group on which I focused my study. I was interested in how MGTOW, an exclusively male, antifeminist group related to past feminist movements in theory, activism and community structure. I sought to understand how the internet affects “antifeminist” identity formation and articulation of views. Like many other antifeminist 1 | On May 23, 2014 Elliot Rodger, a 22-year old, killed six and injured 14 people in Isla Vista—near the University of California, Santa Barbara campus—as an act of retribution toward women who didn’t give him attention, and men who took those women away from him. Rodger kept a diary for three years in anticipation of his “endgame,” and subscribed to antifeminist “Pick-Up Artist” videos. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/05/26/justice/ california-elliot-rodger-timeline/ Accessed: March 28, 2016. 2 | #gamergate refers to a campaign of intimidation of female game programmers: Zoë Quinn, Brianna Wu and feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian, from 2014 to 2015. -

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar Ve Yorumlar

Thales of Miletus Sources and Interpretations Miletli Thales Kaynaklar ve Yorumlar David Pierce October , Matematics Department Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul http://mat.msgsu.edu.tr/~dpierce/ Preface Here are notes of what I have been able to find or figure out about Thales of Miletus. They may be useful for anybody interested in Thales. They are not an essay, though they may lead to one. I focus mainly on the ancient sources that we have, and on the mathematics of Thales. I began this work in preparation to give one of several - minute talks at the Thales Meeting (Thales Buluşması) at the ruins of Miletus, now Milet, September , . The talks were in Turkish; the audience were from the general popu- lation. I chose for my title “Thales as the originator of the concept of proof” (Kanıt kavramının öncüsü olarak Thales). An English draft is in an appendix. The Thales Meeting was arranged by the Tourism Research Society (Turizm Araştırmaları Derneği, TURAD) and the office of the mayor of Didim. Part of Aydın province, the district of Didim encompasses the ancient cities of Priene and Miletus, along with the temple of Didyma. The temple was linked to Miletus, and Herodotus refers to it under the name of the family of priests, the Branchidae. I first visited Priene, Didyma, and Miletus in , when teaching at the Nesin Mathematics Village in Şirince, Selçuk, İzmir. The district of Selçuk contains also the ruins of Eph- esus, home town of Heraclitus. In , I drafted my Miletus talk in the Math Village. Since then, I have edited and added to these notes. -

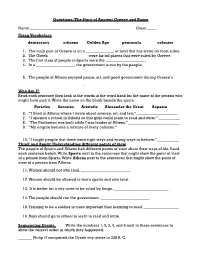

Questions: the Story of Ancient Greece and Rome

Questions: The Story of Ancient Greece and Rome Name ______________________________________________ Class _____ Using Vocabulary democracy citizens Golden Age peninsula colonies 1. The main part of Greece is on a ______________, or land that has water on most sides. 2. The Greek ____________________ were far-off places that were ruled by Greece. 3. The first class of people in Sparta were the ____________________. 4. In a ____________________ the government is run by the people. 5. The people of Athens enjoyed peace, art, and good government during Greece’s ____________________________. Who Am I? Read each sentence then look at the words in the word bank for the name of the person who might have said it. Write the name on the blank beside the quote. Pericles Socrates Aristotle Alexander the Great Aspasia 6. “I lived in Athens where I wrote about science, art, and law.” _____________________ 7. “I opened a school in Athens so that girls could learn to read and write.” ___________ 8. “The Parthenon was built while I was leader of Athens.” __________________________ 9. “My empire became a mixture of many cultures.” _______________________________ 10.“I taught people that there were right ways and wrong ways to behave.” ___________ Think and Apply: Understanding different points of view The people of Sparta and Athens had different points of view about their ways of life. Read each sentence below. Write Sparta next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Sparta. Write Athens next to the sentences that might show the point of view of a person from Athens. -

1 Foreigners As Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato's

1 Foreigners as Liberators: Education and Cultural Diversity in Plato’s Menexenus Rebecca LeMoine Assistant Professor of Political Science Florida Atlantic University NOTE: Use of this document is for private research and study only; the document may not be distributed further. The final manuscript has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form in The American Political Science Review 111.3 (August 2017). It is available for a FirstView online here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000016 Abstract: Though recent scholarship challenges the traditional interpretation of Plato as anti- democratic, his antipathy to cultural diversity is still generally assumed. The Menexenus appears to offer some of the most striking evidence of Platonic xenophobia, as it features Socrates delivering a mock funeral oration that glorifies Athens’ exclusion of foreigners. Yet when readers play along with Socrates’ exhortation to imagine the oration through the voice of its alleged author Aspasia, Pericles’ foreign mistress, the oration becomes ironic or dissonant. Through this, Plato shows that foreigners can act as gadflies, liberating citizens from the intellectual hubris that occasions democracy’s fall into tyranny. In reminding readers of Socrates’ death, the dialogue warns, however, that fear of education may prevent democratic citizens from appreciating the role of cultural diversity in cultivating the virtue of Socratic wisdom. Keywords: Menexenus; Aspasia; cultural diversity; Socratic wisdom; Platonic irony Acknowledgments: An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 annual meeting of the Association for Political Theory, where it benefitted greatly from Susan Bickford’s insightful commentary. Thanks to Ethan Alexander-Davey, Andreas Avgousti, Richard Avramenko, Brendan Irons, Daniel Kapust, Michelle Schwarze, the APSR editorial team (both present and former), and four anonymous referees for their invaluable feedback on earlier drafts. -

8 Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer What Might Philosophy Say At

��8 Book Reviews Nickolas Pappas and Mark Zelcer Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s Menexenus: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History (London; New York: Routledge, 2015), vii + 236 pp. $140.00. ISBN 9781844658206 (hbk). What might philosophy say at the burial of citizens who died in war? No sooner is this timely question raised that we must acknowledge that it is far from obvious what the philosopher would say. Civic funerals are moments in political life where the philosopher is confronted by contingency, by a blow to the body politic of which she is part, where she must either speak or keep silent. The confrontation is the subject of Pappas and Zelcer’s book, Politics and Philosophy in Plato’s ‘Menexenus’. The couplings in its subtitle reveal the main ingredients of philosophic speech: Education and Rhetoric, Myth and History. The Menexenus, the authors write, ‘show[s] philosophy bringing a pedagogical impulse to funeral rhetoric that the Republic says philosophical rulers would bring to all aspects of governing a city’ (p. 99). Plato acknowledges the ‘magic of rhetoric’ (p. 136), and the relationship between philosophy and rhetoric is analogous to the relationship between philosophy and politics: in both cases philosophy is the superior partner and the driving force. For Plato, Pappas and Zelcer conclude, the dead are to be ‘buried in philosophy’ (p. 220). Since one cannot assume a ready familiarity with the Menexenus, here is a brief summary. Plato raises Socrates from the dead to converse with the young Menexenus, as the city is poised to commemorate those who died in Athens’ defeat at the end of the Corinthian War in 386 BC. -

Isocrates' Encomium of Helen and the Cult of Helen and Menelaus At

Isocrates’ Encomium of Helen and the Cult of Helen and Menelaus at Therapnē Lowell Edmunds Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey [email protected] The main sources in Greek literature for the cult of Helen and/or Menelaus at Therapnē are Herodotus (6.61.3), Isocrates 10 (Encomium of Helen), and Pausanias (3.19.9-10). Isocrates is the one who speaks of joint-worship of Helen and Menelaus (10.63). He suggests, furthermore, that Helen was a goddess at Therapnē, and his Encomium is routinely cited for her divine status in this cult, and not only by scholars of myth and literature. Archaeologists, too, have appealed to the Encomium as a documentary source for their interpretation of the site, the so-called Menelaion (first by Polybius 5.18.4). Much disagreement prevails, within the two fields of classical studies just mentioned, and also between them.1 The present article does not attempt to adjudicate. It 1 Accounts of Helen in the history of Greek religion differ in the weight assigned Isoc. 10. Harder 2006, in the New Pauly, s.v. “Helena,” begins: “Goddess who was worshipped at various cult sites in and around Sparta, especially in the Menelaion in Therapnē,” citing Hdt., Paus., and Hsch. but not Isoc. Similarly, for the Therapnē cult Calame 1997 196-99 (also 194, 200-201, 232) builds his interpretation on Hdt., citing Isoc. 10 only in a n., for the joint worship of Helen and Menelaus (196 n. 331). Others, like Nilsson (cf. Edmunds 2007: 16, 20-24, which the present article amplifies), who see in Helen the avatar of a Minoan or “Old European” vegetation goddess, routinely cite Isoc. -

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: a Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis

Women and Property in Ancient Athens: A Discussion of the Private Orations and Menander Cheryl Cox University of Memphis There has been a great deal of discussion in the past two decades or so among social historians and anthropologists of the proposition that women in European societies, both in the past and in the present, have informal power at the private level of the household. Women’s interests were reflected and expressed in succession practices and in the management of the household economy. Central to the status of women was the dowry because of its place in the conjugal household and the negotiations over its use and transmission. A large dowry ensured the woman’s important role in the decisions of the marital household and thus helped to stabilize the marriage. Because the dowry, as the property of the woman’s natal kin, would ideally be transmitted to the man’s children, the man could become involved in the property interests of his wife’s family of origin.1 In a material sense, in classical Athens the wife’s dowry allowed for the cohesion of two households (oikoi): the oikos of her marriage and that of her natal family. The dowry in legal terms belonged to the woman’s natal family, as it had to be returned to her family of origin either on divorce or on the death of her husband and her remarriage. Much of the information we have for dowries pertains to elite families. Because the woman’s dowry could be inherited by the children, it was worth fighting for, especially if she had not received her full share (Dem.