Scenes from a Crowded Classroom: Teaching Theatrical Blocking in English Language Arts Leah Zuidema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander

Blocking Fathers, Illicit Marriages: Continuity and Change from Sophocles to Menander It is a truth universally acknowledged that the plays of Menander owe a great debt to Classical Athenian drama: connections between plays such as Aristophanes’ Cocalus and Menander were noted in didascalia, and similarly the thematic and structural similarities between New Comedy and the works of Euripides were already recognized in Hellenistic scholarship (Arnott 1972; Csapo 2000; Hunter 2011). Sophocles, on the other hand, is rarely included in this discussion of dramatic influence, more often regarded solely for his role as the pinnacle of tragic poets. It is the purpose of this paper to reanalyze possible connections between the corpus of Sophocles and that of Menander by examining both the Antigone and the Dyscolus as plays employing one of the most familiar stock characters of ancient comedy: the “blocking” father figure. This father figure—whose earliest incarnation arguably belongs to Old Comedy, such as Strepsiades from Clouds—is perhaps best known for his characterization in the plays of Greek New Comedy and their later, Latin iterations. Generally an old and intransigent father, the “blocking” figure is generically defined by his interference in the life of his young offspring; in New Comedy, this interference takes the form of intervention in the budding romance of two young lovers, whose inconvenient marriage will inevitably bring about the typical finale. This character, at first glance, may appear to be a creature created solely for light-hearted drama. Creon of the Antigone, however, whose stubborn and belligerent character has been carefully surveyed for his role within the tragedy itself (see Roisman 1996), additionally shares many features with the father of Menander’s only intact play, Knemon of the Dyscolus. -

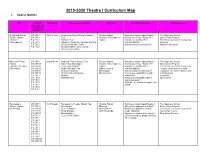

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I

2019-2020 Theatre I Curriculum Map I. Course Outline Unit Current Timeframe Assessments/Activities Big Idea Essential Questions Core Resources Arkansas SS Framework Alignment Greek and Roman CR.1.TH.1 1st 9 Weeks Greeks and Roman Theatre History Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School Theatre History P.4.THI.2 Test Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character P.4.THI.3 Antigone Test Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Development P.4.THI.5 Napoleon Dynamite Character Analysis characterization? Antigone P.5.THI.2 Life Size Character Poster How do characters affect plot? Napoleon Dynamite P.6.THI.2 Character Observation Journal Greek Theatre Mask Medieval Theatre CR.1.TH.1 2nd 9 Weeks Medieval Theatre History Test Theatre History How does history impact theatre? The Stage and School History CR.2.THI.1 Solo Acting Monologue Character Development How do you create characters? Basic Drama Projects Character Creation CR.2.THI.2 Theme Assessment Improv How does empathy affect The Drama Classroom Companion Solo Acting CR.1.THI.3 Modern Morality Play Acting Theories characterization? Veggies Tales used as modern CR.1.THI.4 Character Analysis Monologues How do characters affect plot? (examples of mystery, miracle, and CR.3.THI.1 Character Design Morgue Memorization How do you establish believable morality plays) P.5.THI.1 Audition characters? Everyman P.5.THI.2 Self Reflection How does memorization affect Monologues P.5.THI.4 characterization? P.5.THI.5 -

A GLOSSARY of THEATRE TERMS © Peter D

A GLOSSARY OF THEATRE TERMS © Peter D. Lathan 1996-1999 http://www.schoolshows.demon.co.uk/resources/technical/gloss1.htm Above the title In advertisements, when the performer's name appears before the title of the show or play. Reserved for the big stars! Amplifier Sound term. A piece of equipment which ampilifies or increases the sound captured by a microphone or replayed from record, CD or tape. Each loudspeaker needs a separate amplifier. Apron In a traditional theatre, the part of the stage which projects in front of the curtain. In many theatres this can be extended, sometimes by building out over the pit (qv). Assistant Director Assists the Director (qv) by taking notes on all moves and other decisions and keeping them together in one copy of the script (the Prompt Copy (qv)). In some companies this is done by the Stage Manager (qv), because there is no assistant. Assistant Stage Manager (ASM) Another name for stage crew (usually, in the professional theatre, also an understudy for one of the minor roles who is, in turn, also understudying a major role). The lowest rung on the professional theatre ladder. Auditorium The part of the theatre in which the audience sits. Also known as the House. Backing Flat A flat (qv) which stands behind a window or door in the set (qv). Banjo Not the musical instrument! A rail along which a curtain runs. Bar An aluminium pipe suspended over the stage on which lanterns are hung. Also the place where you will find actors after the show - the stage crew will still be working! Barn Door An arrangement of four metal leaves placed in front of the lenses of certain kinds of spotlight to control the shape of the light beam. -

Stage Manager & Assistant Stage Manager Handbook

SM & ASM HANDBOOK Victoria Theatre Guild and Dramatic School at Langham Court Theatre STAGE MANAGER & ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER HANDBOOK December 12, 2008 Proposed changes and updates to the Producer Handbook can be submitted in writing or by email to the General Manager. The General Manager and Active Production Chair will enter all approved changes. VTG SM HANDBOOK: December 12, 2008 1 SM & ASM HANDBOOK Stage Manager & Assistant SM Handbook CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. AUDITIONS a) Pre-Audition b) Auditions and Callbacks c) Post Auditions / Pre First Rehearsal 3. REHEARSALS a) Read Through / First Rehearsal b) Subsequent Rehearsals c) Moving to the Mainstage 4. TECH WEEK AND WEEKEND 5. PERFORMANCES a) The Run b) Closing and Strike 6. SM TOOLS & TEMPLATES 1. Scene Breakdown Chart 2. Rehearsal Schedule 3. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Guidelines for Stage Management 4. The Prompt Book VTG SM HB: December 12, 2008 2 SM & ASM HANDBOOK 5. Production Technical Requirements 6. Rehearsals in the Rehearsal Hall – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 7. Rehearsal Attendance Sheet 8. Stage Management Kit 9. Sample Blocking Notes 10. Rehearsal Report 11. Sample SM Production bulletins 12. Use of Theatre during Rehearsals on Mainstage – SM Guidelines 13. Rehearsals on the Mainstage – Information sheet for Cast & Crew 14. Sample Preset & Scene Change Schedule 15. Performance Attendance Sheet 16. Stage Crew Guidelines and Information Sheet 17. Sample Prompt Book Cues 18. Use of Theatre during Performances – SM Guidelines 19. Sample Production Information Sheet for FOH & Bar 20. Sample SM Preshow Checklist 21. Sample SM Intermission Checklist 22. SM Post Show Checklist 23. -

New Directions for Kabuki Performances in America in the 21St Century

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 4-2-2019 New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21st Century Narumi Iwasaki Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Iwasaki, Narumi, "New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21st Century" (2019). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4942. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6818 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. New Directions For Kabuki Performances in America in the 21 st Century by Narumi Iwasaki A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Japanese Thesis Committee: Laurence Kominz, Chair Suwako Watanabe Jon Holt Portland State University 2019 ©2019 Narumi Iwasaki i Abstract Transitions from the first kabuki performance abroad in Russia in 1928 to the recent performances around the world show various changes in the purpose and production of kabuki performances overseas. Kabuki has been performed as a Japanese traditional art in the U.S. for about 60 years, and the United States has seen more kabuki than any other country outside of Japan. Those tours were closely tied to national cultural policy of both Japan and the USA in the early years (Thornbury 2–3). -

An Introduction to Theatre

STAGE DIRECTIONS TYPES, AND POSITIONS VOCABULARY •Proscenium Stage- A traditional stage that includes a proscenium arch. The audience sits on one side. • Arena Stage- A theatre in the round. The stage is in the center with the audience sitting on all sides. •Thrust Stage- A theatre where the front part of the stage juts out into the audience, similar to a runway. Audience sits on three sides. •Flexible Staging- A theatre that can be changed to meet your needs, typically a black box theatre, but could include theatre in unconventional places. •Stage Directions- Directions of where to be and go onstage. Always given from the point of view of the actor. •Stage Positions- The position of the actors body in relation to the Audience LESSON OBJECTIVES: The Student will: •Be able to identify all types of stages. •Respond to stage directions appropriately. •Choose and execute all body positions for the appropriate effect. PROSCENIUM STAGE A proscenium stage is what most of us think of when we think of a stage. It includes a proscenium arch which creates the 4th wall. This is the invisible boundary that separates the performers from the audience. The audience only sits on one side of the stage. ARENA STAGE Arena stages have people sitting on all sides of the stage. It creates an intimate space but creates problems for actors and the creative team because it is hard to control the sight lines, or what the audience can see. Why do you think this would this be a problem? THRUST STAGE With a thrust stage the audience is seated on three sides of the stage, kind of like a runway. -

Assignment 1: Theatre Blocking Assignment Handout

CSC301 Winter 2020 Assignment 1: Theatre Blocking Assignment Handout Due date: Friday, Jan 31st by 11:59pm. This assignment is done Pairs. Overview In this assignment, you will be combining Product Management skills with some web programming to create a small web app. Although you will be doing some coding and using web technologies, the focus is not on how well you can code, or on how fancy you can make your project look. It will be on how you define your users, work out a plan with them in mind, and then develop a solution based on your well-thought out assumptions. In the sections that follow, we will give you a specification of a particular app. Most of your grade (80%) will come from following our specifications. However, to potentially receive full marks, you will have to add some enhancements on top of the work you do. These must also follow some rules we give you and should tie in to the course material. This is in line with the Arts and Science guidelines for A+: "Strong evidence of original thinking; good organization; capacity to analyze and synthesize; superior grasp of subject matter with sound critical evaluations; evidence of extensive knowledge base." Starter Files/GitHub Repo First Steps You must create your pair on Quercus by navigating to the ‘People’ tab, and clicking ‘Assignment 1 Pairs’. Only one team member should do this. Your partner can simply join the pair on Quercus once you have created it. Please use the following team name and git repo name structure: utorid1_utorid2_a1. -

Theatre Promptbook

Theatre Promptbook A promptbook is an essential tool used in building a theatre production. A promptbook contains copies of the script and records the thinking, interpreting, staging, costumes, props etc. of the play. A critical aspect of the prompt book is CHOICE-- supported by the text and your vision. YOU make choices about how lines might be delivered, how the actors move; as well as experiment with ways to stage your play—including the props, set, makeup, lights, sound, and costumes. Required Materials A. You need a 3 ringed binder B. Single-sided photo copies of the pages in the play; *play should have your final blocking and directing notes on it C. Given Circumstances WS D. Character Analysis WS (1 copy for each character: protagonist and antagonist) Set Up 1. Cover Page (Title of Play, Playwright’s Name, Director’s Name) Title of Play By: ______ Director: ______ 2. Given Circumstances WS 3. Character Analysis WS 4. Prompt Book entries: Set Design; Costume List; Prop List; Paraphrasing of play, Design element and rendering, Copy of scene (not double sided) with blocking, and final directing notes (also cues may go on this if that’s the design element you chose to do). Prompt Book Procedures: I. Read through and study your play (NO MUSICALS!) then select one scene you’d like to stage. A. Circle any unfamiliar words; define them in the margin 1. Use a dictionary or footnotes 2. Use the playwright’s notes, if there are any 3. Use an on-line source B. Write a Concept Paper: The Concept Paper is an analysis of a play and must consist of the following: 1. -

CHAPTER 9: Taking the Stage ■ 149 Ow It Is Time to Think About Taking Your Scene Or Play to the Stage for Re- N Hearsal and Production

9 Taking the Stage LESSON 1 ◆ Types of Stages 150 LESSON 2 ◆ Stage Terminology 154 LESSON 3 ◆ Acting Technique 157 ◆ acting areas ◆ level ◆ apron ◆ planes ◆ arena stage ◆ proscenium stage ◆ blocking ◆ stage ◆ body positions ◆ stage picture ◆ flexible staging ◆ thrust stage ◆ grand drape ◆ wings ◆ house ■ CHAPTER 9: Taking the Stage ■ 149 ow it is time to think about taking your scene or play to the stage for re- N hearsal and production. In this chapter, you will be introduced to dif- ferent types of stages and to the specialized language used in directing and staging a play. You will begin to see why acting requires a great deal of hard work, intense discipline, and years of training. Types of Stages LESSON OBJECTIVES ◆ Understand performance space. 1 ◆ Recognize basic types of stages. A play must have a performance space. This space should provide a stage , or area where the players perform, and a separate area where the audience watches. The stage in your school might be in a theatre ith your acting company, or auditorium, or it might be part of the classroom. A performance W discuss how the stages at your school differ from the space can be any area designated for acting that is set apart from the stages illustrated in this audience. textbook. Where are the stages located in your school? What The Proscenium Stage other events take place in those spaces? The most common stage in educational theatre is the proscenium stage. A proscenium stage is usually a raised picture-frame stage, or box stage (see Figure 9–1). -

From Start to Strike: a Lesson Plan for the Whole Theatre Experience Kelly Crotty University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Outstanding Honors Theses Honors College 4-1-2011 From Start to Strike: A Lesson Plan for the Whole Theatre Experience Kelly Crotty University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/honors_et Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Crotty, Kelly, "From Start to Strike: A Lesson Plan for the Whole Theatre Experience" (2011). Outstanding Honors Theses. Paper 10. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/honors_et/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Outstanding Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Theatre Experience Lesson Plans for a High School Theatre Class Kelly Crotty April 2011 College of the Arts School of Theatre & Dance Theatre Arts Mentor: Dr. Patrick Finelli Contents Interviews………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………………………….….….3-5 Sunshine State Standards for Drama………………………………..………………………………………………………….…..….6-7 FLDOE Comprehensive Theatre Course Description…………….………….……………………………………….…….….8-11 Syllabus……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………..12 Lesson Plans…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……...14-89 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….90-91 Interviews What field is your degree in? James Thompson: I have a BA in Theatre and a BS in English Teaching Edwin Velazquez: B.A. in English Language Arts with a minor in theater arts and another in Education. Master's in Interdisciplinary Studies When did you first become interested in drama/theatre? JT: I first became interested in acting and the theatre in the 3rd grade when my class was chosen to write the St. Patrick’s Day play for our school. -

Glossary: Theatre Terms

GLOSSARY: THEATRE TERMS Created by Betsy Anne Huggins, Director of Education and Community Engagement Theatre/Theater: these words are interchangeable for many, but in the business, most practitioners spell theatre with an “re” when referring to the art form or a business that creates live performing arts. Theater with an “er” refers to the physical space where we perform the art. Before the Show: Once a director or producer decides to perform a show, the work begins! Casting: the process of selecting actors to play specific roles in a performance. Breakdown: a list of the roles that need to be filled by actors. It may also contain information about gender, age, race, and any behavioral characteristics that need to be taken into account when casting. Side: a short selection of the script that can be used to cast a play. Actors can try out various roles and are often coached on their performance by the director or casting agent. Callback: a smaller audition when actors are invited back to further audition for a play. Rehearsal Hall with Rick Dildine Rehearsal Process: Actors join the director in a rehearsal space to begin crafting the performance. Blocking: the method of choreographing the movement of actors, sets, and props onstage. During the rehearsal process, the stage manager tracks this information using blocking notation. Most stage managers work from a standard blocking diagram: Cross: blocking where an actor moves across the stage; it’s typically marked as an “X” in a stage manager’s script. Blocking Diagram Off Book: when actors are expected to have learned their lines and blocking so that they can perform without a script in hand. -

Keep Moving Forward Saturday, May 13

KEEP MOVING FORWARD SATURDAY, MAY 13 Show #1 Show #2 Show #3 9:30 AM 11:30 AM 2:30 PM BISHOP MCGUINNESS HIGH SCHOOL The recital offers our students a professionally directed performance that allows them a chance to shine onstage and share what they have learned over the year! One redit Costu et C me ick & A 0 T lte $4 ra tio ns O s n k e c P a a n i S r o & f s T r i g e t h t i t s S y D t i V r D u c e S 5 X t r 7 i h G S r - o T u l p a t P i c h e o t R o THE INVESTMENT VDC’s recital package includes everything you need for a successful performance! It includes: 1 costume and 1 pair tights for one class, alterations on all costumes (as needed), 1 DVD, 1 5X7 group photo, recital T-Shirt, backstage security, backstage sitters, snacks during the performances and $40 recital ticket credit. DANCER FEE DANCER IN A FAMILY ADDITIONAL COSTUMES $280.00 $240.00 $75.00 All accounts must be up to date and be paid in full before the dance recital. Students will NOT be able to participate in the dance recital if the account balance has not been paid in full by May 6th. Each student will be assigned a student ID number. Student ID numbers are used to help us easily and efficiently organize costumes, manage the backstage, and efficiently check students in and out.