Author's Personal Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽabbāsid Art: Squinch Fragmentation As The

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽAbbāsid Art: squinch fragmentation as The structural origin of the muqarnas La tradición sasánida en el arte ʿabbāssí: la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina como origen estructural de la decoración de muqarnas A tradição sassânida na arte abássida: a fragmentação do arco de canto como origem estrutural da decoração das Muqarnas Alicia CARRILLO1 Abstract: Islamic architecture presents a three-dimensional decoration system known as muqarnas. An original system created in the Near East between the second/eighth and the fourth/tenth centuries due to the fragmentation of the squinche, but it was in the fourth/eleventh century when it turned into a basic element, not only all along the Islamic territory but also in the Islamic vocabulary. However, the origin and shape of muqarnas has not been thoroughly considered by Historiography. This research tries to prove the importance of Sasanian Art in the aesthetics creation of muqarnas. Keywords: Islamic architecture – Tripartite squinches – Muqarnas –Sasanian – Middle Ages – ʽAbbāsid Caliphate. Resumen: La arquitectura islámica presenta un mecanismo de decoración tridimensional conocido como decoración de muqarnas. Un sistema novedoso creado en el Próximo Oriente entre los siglos II/VIII y IV/X a partir de la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina, y que en el siglo XI se extendió por toda la geografía del Islam para formar parte del vocabulario del arte islámico. A pesar de su importancia y amplio desarrollo, la historiografía no se ha detenido especialmente en el origen formal de la decoración de muqarnas y por ello, este estudio pone de manifiesto la influencia del arte sasánida en su concepción estética durante el Califato ʿabbāssí. -

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner Islamic Geometric Patterns Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction with a chapter on the use of computer algorithms to generate Islamic geometric patterns by Craig Kaplan Jay Bonner Bonner Design Consultancy Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA With contributions by Craig Kaplan University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada ISBN 978-1-4419-0216-0 ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0217-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936979 # Jay Bonner 2017 Chapter 4 is published with kind permission of # Craig Kaplan 2017. All Rights Reserved. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

DTP102288.Pdf

Contents 1. SELECTED HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ................................................................... 2 2. PROJECT OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................ 4 3. PROJECT ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................... 4 3.1 ENABLING WORKS ................................................................................................ 5 3.1.1 Fencing: ............................................................................................................. 5 3.1.2 Scaffolding: ........................................................................................................ 5 3.1.3 Clearance Works: .............................................................................................. 5 3.1.4 Excavations: ...................................................................................................... 5 3.2 CONSOLIDATION WORKS: ................................................................................... 6 3.2.1 Dismantling of previous works and reconstruction of buttresses: ..................... 6 3.2.2 Structural Consolidation: ................................................................................... 6 3.2.3 Construction of timber cover: .......................................................................... 11 3.2.4 External Finishes: ............................................................................................ 11 4. PROJECT DATA .......................................................................................................... -

Geometric Analysis of Forumad Mosques' Ornaments

Proceedings of Bridges 2013: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Geometric Analysis of Forumad Mosques’ Ornaments Mahsa Kharazmi Reza Sarhangi Department of Art and Architecture Department of Mathematics Tarbiat Modares University Towson University Jalale Ale Ahmad Highway, Tehran, Iran Towson, Maryland, 21252 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This article analyzes the architectural designs and ornaments of a 12th century structure in Iran. Friday Mosque of Forumad, Masjid-i Jami' Forumad is a prototype mosque in Persian architecture using an application of ornaments. Architectural ornaments are important examples of practical geometry. The brilliant stucco ornaments, elaborate strapwork patterns with turquoise and cobalt blue, and floral motifs with underlying geometric patterns, made this mosque a worthwhile building in early Iranian-Islamic period. By introducing the mosque’s features, the ornaments that adorn some of the walls will be analyzed and geometric methods for constructing their underlying designs will be presented. 1 Introduction Early mosques were simple buildings with no decoration. After some decades and under the influence of advanced civilizations of conquered territories, architectural ornaments entered into their existence. Since Islamic thought prohibited artists and craftsmen of creating human figures, they turned their attention to abstract forms. They also benefited from mathematics, which flourished in early Islamic period in Baghdad. This resulted to a widespread movement in Islamic geometric art. Even though the designers of those structures had remarkable knowledge of applied geometry, there exist few written records to explain various methods that they employed for constructions of their designs [7]. Nevertheless, based on the detailed and sophisticated geometric designs in these documents we may suggest that some degree of mathematical literacy may have existed among the master builders, architects and master engineers [1]. -

Arh 362: Islamic Art

ARH 362: ISLAMIC ART CLUSTER REQUIREMENT: 4C, THE NATURE OF GLOBAL SOCIETY COURSE DESCRIPTION This course surveys the art and architecture of the Islamic world from the 7th through the 20th centuries. By looking at major themes and regional variations of Islamic art and architecture, the course examines how meanings in various socio-political and historical contexts have been encoded through forms, functions, as well as the aesthetic features of arts, crafts, and the built environment. The last portion of the course, spanning the 19th to the late 20th centuries, examines the West’s discovery of the Islamic arts as well as the integration of Western ideas into indigenous ones. This course can only briefly address some of the major themes. The topics (especially those pertinent to the modern period) are introduced through a number of key readings, but they should be merely seen as introductions, providing possible directions for future and more advanced studies. Discussions and questions are always encouraged. The readings, which have been selected to supplement the required textbooks, are particularly chosen to serve this purpose. COURSE-SPECIFIC OUTCOMES Gain valuable information about Islamic art and design as well as the cultures that gave shape to them Read critically and interpret and evaluate art historical issues in relation to socio-political conditions in non-Western contexts Develop a foundation for writing good critical essays about non-Western art and material culture Research non-Western art in a museum context Comparative studies of Western and Non-Western styles in a variety of media, including 2D and 3D art and design as well as architecture. -

Ijarset 13488

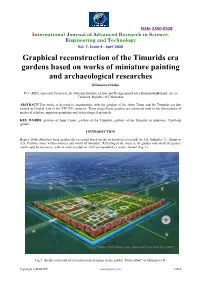

ISSN: 2350-0328 International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 4 , April 2020 Graphical reconstruction of the Timurids era gardens based on works of miniature painting and archaeological researches GilmanovaNafisa P.G. (PhD), Associate Professor, the National Institute of Arts and Design named after KamoliddinBehzad, city of Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan ABSTRACT:This article is devoted to acquaintance with the gardens of the Amir Timur and the Timurids era that existed in Central Asia in the XIV-XV centuries. These magnificent gardens are preserved only in the descriptions of medieval scholars, miniature paintings and archaeological materials. KEY WORDS: gardens of Amir Timur, gardens of the Timurids, gardens of the Timurids in miniature, Charbagh garden. I.INTRODUCTION Bagh-e Dolat-Abad has been graphically recreated based on the archaeological records by I.A. Sukharev, U. Alimova, A.S. Uralova, some written sources and works of miniature. Referring to the sources, the garden was small, the palace itself could be two-story, with an iwan, located on a hill surrounded by a water channel (Fig. 1). Fig 1. Architectural and art reconstruction of image of the garden “Dolat-Abad” of Gilmanova N. Copyright to IJARSET www.ijarset.com 13488 ISSN: 2350-0328 International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Engineering and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 4 , April 2020 Bagh-e Dolat-Abad Garden, located south of Samarkand, was built upon the return of Amir Timur from the Indian campaign in 1399. Describing the Dolat-Abad Garden, from which only architectural fragments of the foundation of the magnificent palace on a hill were preserved, Clavijo stated: “Clay rampart surrounded the garden. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

The Elements of Local and Non-Local Mosque Architecture for Analysis of Mosque Architecture Changes in Indonesia

The International Journal of Engineering and Science (IJES) || Volume || 7 || Issue || 12 Ver.I || Pages || PP 08-16 || 2018 || ISSN (e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN (p): 23-19 – 1805 The Elements of Local and Non-Local Mosque Architecture for Analysis of Mosque Architecture Changes in Indonesia Budiono Sutarjo1, Endang Titi Sunarti Darjosanjoto2, Muhammad Faqih2 1Student of Doctoral Program, Department of Architecture, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia 2Senior Lecturer, Department of Architecture, Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember (ITS), Surabaya, Indonesia Corresponding Author : Budiono Sutarjo --------------------------------------------------------ABSTRACT---------------------------------------------------------- The mosque architecture that deserves to use as a starting point in the analysis of architectural changes in Indonesian mosques is the Wali mosque as an early generation mosque in Indonesia. As a reference, the architectural element characteristic of Wali mosque (local mosque) needs to be known, so that this paper aims to find a description of a local mosque (Wali mosque), and also description of architectural elements of non- local mosques (mosques with foreign cultural context) because one of the causes of changes in mosque architecture is cultural factors. The findings of this paper are expected to be input for further studies on the details of physical changes in the architectural elements of mosques in Indonesia. The study subjects taken were 6 Wali mosques that were widely known by the Indonesian Muslim community as Wali mosques and 6 non-local mosques that were very well known and frequently visited by Indonesian Muslim communities. Data obtained from literature studies, interviews and observations. The analysis is done by sketching from visual data, critiquing data, making interpretations, making comparisons and compiling the chronology of the findings. -

Islamic Architecture Islam Arose in the Early Seventh Century Under the Leadership of the Prophet Muhammad

Islamic Architecture Islam arose in the early seventh century under the leadership of the prophet Muhammad. (In Arabic the word Islam means "submission" [to God].) It is the youngest of the world’s three great monotheistic religions and follows in the prophetic tradition of Judaism and Christianity. Muhammad leads Abraham, Moses and Jesus in prayer. From medieval Persian manuscript Muhammad (ca. 572-632) prophet and founder of Islam. Born in Mecca (Saudi Arabia) into a noble Quraysh clan, he was orphaned at an early age. He grew up to be a successful merchant, then according to tradition, he was visited by the angel Gabriel, who informed him that he was the messenger of God. His revelations and teachings, recorded in the Qur'an, are the basis of Islam. Muhammad (with vailed face) at the Ka'ba from Siyer-i Nebi, a 16th-century Ottoman manuscript. Illustration by Nakkaş Osman Five pillars of Islam: 1. The profession of faith in the one God and in Muhammad as his Prophet 2. Prayer five times a day 3. The giving of alms to the poor 4. Fasting during the month of Ramadan 5. The hajj, or pilgrimage to Mecca Kaaba - the shrine in Mecca that Muslims face when they pray. It is built around the famous Black Stone, and it is said to have been built by Abraham and his son, Ishmael. It is the focus and goal of all Muslim pilgrims when they make their way to Mecca during their pilgrimage – the Hajj. Muslims believe that the "black stone” is a special divine meteorite, that fell at the foot of Adam and Eve. -

Nano Particles and Nano Composites for Preservation of Historic Marble

Open Journal of Geology, 2019, 9, 957-973 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ojg ISSN Online: 2161-7589 ISSN Print: 2161-7570 Nano Particles and Nano Composites for Preservation of Historic Marble Minbars with Application on the Minber of Soliman Pasha Al-Khadim Mosque in Salah El-Din Citadel in Cairo, Egypt Mohamed Abd El Hady, Sayed Hemada* , Mahmoud Algohary Conservation Department, Faculty of Archaeology, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt How to cite this paper: El Hady, M.A., Abstract Hemada, S. and Algohary, M. (2019) Nano Particles and Nano Composites for Preser- Minbar, in Islam, the pulpit from which the sermon (khutbah) is delivered. In vation of Historic Marble Minbars with its simplest form, the minbar is a platform with three steps. Often it is con- Application on the Minber of Soliman structed as a domed box at the top of a staircase and is reached through a Pasha Al-Khadim Mosque in Salah El-Din Citadel in Cairo, Egypt. Open Journal of doorway that can be closed. Soliman pasha Al-Khadim mosque in Salah Geology, 9, 957-973. El-Din citadel in Cairo is considered the first mosque with ottoman architec- https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2019.913099 tural style. This Minbar exposed to aggressive human intervention by mosque workers and archaeological crafts unity-ministry of antiquities in Egypt, to Received: November 24, 2019 Accepted: December 16, 2019 lose more of its historical and architectural values. Now this Minbar under- Published: December 19, 2019 goes restoration process, they are removing all modern pigments and remains of last reconstruction in 2014 so we proposed some Nano particles and Nano Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. -

Muslim Architecture Under Ottoman Patronage (1326-1924)

Muslim Architecture under Ottoman Patronage (1326-1924) IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Rabah Saoud BA MPhil PhD Chief Editor: Lamaan Ball All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Production: Faaiza Bashir accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: July 2004 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 4064 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2003 2004 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

The Monumental Iwan: a Symbolic Space Or a Functional Device ?

METUJFA 1991 (11:1-2) 5-19 THE MONUMENTAL IWAN: A SYMBOLIC SPACE OR A FUNCTIONAL DEVICE ? Ali Uzay PEKER INTRODUCTION Received : 27.1.1993 The architectural unit iwan consists of an empty vaulted space enclosed on three KeyWords: History of Architecture, Iwan, Courtyard with Four Cross-Axial Iwans, sides and open to a courtyard or central space on the fourth (Figure 1). Even Cosmology and Architecture. though the history of its application on a monumental scale is characterized by modifications that appear subtle and mainly related to periodic changes in taste, 1. This article is based on a lecture given the iwan was subject to continuous variation and interpretation in innumerable by the author on 14th April 1992, at METU small-scaled buildings. This article concerns the monumental iwan, whose persist Faculty of Architecture, with the title of 'Cosmoiogicai Images in the Seijukid ent application seems to have been governed by a definite cosmoiogicai scheme that Monumental Architecture'. The author dictated its orientation and function in the composition of an edifice (1). thanks Bruce Silverberg for reviewing the text. In Persian, iwan means 'portico, open gallery, porch or palace' and the word liwan in Arabic covers the Persian concept (Reuther, 1967,428). In Sassanid architec ture, the monumental iwan was used as an 'audience hair for the receptions of the kings. Its function in the Islamic period has always been a source of discus sion. It is unknown whether iwan served an official function or even whether these spaces were called iwan. Some written sources define the word iwan as a room or hall opening, on the one side, directly or by means of a portico towards outside.