298950V2.Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Identification of Key Pathways and Genes in Dementia Via Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440371; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of Key Pathways and Genes in Dementia via Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karnataka, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.18.440371; this version posted July 19, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract To provide a better understanding of dementia at the molecular level, this study aimed to identify the genes and key pathways associated with dementia by using integrated bioinformatics analysis. Based on the expression profiling by high throughput sequencing dataset GSE153960 derived from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between patients with dementia and healthy controls were identified. With DEGs, we performed a series of functional enrichment analyses. Then, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, modules, miRNA-hub gene regulatory network and TF-hub gene regulatory network was constructed, analyzed and visualized, with which the hub genes miRNAs and TFs nodes were screened out. Finally, validation of hub genes was performed by using receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis. -

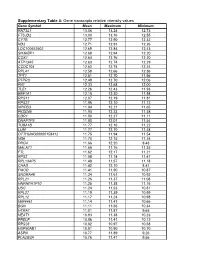

Gene Transcripts Relative Intensity Values

Supplementary Table 4: Gene transcripts relative intensity values Gene Symbol Mean Maximum Minimum RN7SL1 13.06 13.24 12.73 FTSJD2 13.00 13.16 12.55 CYTB 12.77 12.90 12.32 ND2 12.71 12.91 12.26 LOC100652902 12.69 12.84 12.43 SH3KBP1 12.68 12.94 12.20 COX1 12.64 12.76 12.20 ATP13A5 12.63 12.74 12.29 CCDC104 12.62 12.74 12.24 RPL41 12.58 12.66 12.36 TPT1 12.51 12.70 11.96 PTPRO 12.49 12.70 12.06 FN1 12.33 12.68 12.00 TLE1 12.26 12.43 11.93 EEF1A1 12.15 12.30 11.98 RPS11 12.07 12.19 11.81 RPS27 11.96 12.10 11.72 NPIPB3 11.94 12.21 11.65 FKSG49 11.94 12.23 11.58 CDR1 11.90 12.27 11.11 DNAPTP3 11.80 12.07 11.54 TUBA1B 11.77 12.16 11.22 LUM 11.77 12.10 11.48 OTTHUMG00000158412 11.75 11.94 11.54 ND6 11.70 12.15 11.24 PRG4 11.66 12.20 9.43 MALAT1 11.65 11.76 11.35 FTL 11.62 12.17 11.21 RPS2 11.58 11.74 11.47 RPL13AP5 11.48 11.57 11.18 CHAD 11.42 12.10 8.41 FMOD 11.41 11.90 10.87 SNORA48 11.34 11.61 10.92 RPL21 11.26 11.37 11.08 HNRNPA1P10 11.25 11.38 11.16 UBC 11.24 11.53 10.81 RPL27 11.19 11.39 10.99 RPL12 11.17 11.24 10.98 MIR4461 11.14 11.47 10.66 BGN 11.11 11.66 10.34 HTRA1 11.01 11.87 9.65 NEAT1 10.93 11.38 10.23 PRELP 10.86 11.41 10.12 RPS28 10.82 10.97 10.58 HSP90AB1 10.81 10.90 10.70 ASPN 10.77 11.89 9.26 PLA2G2A 10.76 11.47 9.56 H3F3A 10.69 10.86 10.41 EEF1G 10.69 10.94 10.11 C6orf48 10.64 11.02 10.35 UBA52 10.58 10.75 10.08 CTGF 10.57 11.33 9.66 MGP 10.57 11.22 10.09 YBX1 10.56 10.79 10.01 MT1X 10.56 11.89 9.88 NPC2 10.55 10.80 10.12 LAPTM4A 10.51 10.78 10.18 ITM2B 10.51 10.68 10.34 IBSP 10.50 11.50 7.17 NPIPB5 10.50 10.73 10.26 TUBA1A -

Comprehensive Analysis Reveals Novel Gene Signature in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Predicting Is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients

5892 Original Article Comprehensive analysis reveals novel gene signature in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: predicting is associated with poor prognosis in patients Yixin Sun1,2#, Quan Zhang1,2#, Lanlin Yao2#, Shuai Wang3, Zhiming Zhang1,2 1Department of Breast Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China; 2School of Medicine, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China; 3State Key Laboratory of Cellular Stress Biology, School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: Y Sun, Q Zhang; (II) Administrative support: Z Zhang; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Y Sun, Q Zhang; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Y Sun, L Yao; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Y Sun, S Wang; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. #These authors contributed equally to this work. Correspondence to: Zhiming Zhang. Department of Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xiamen University, Xiamen, China. Email: [email protected]. Background: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC) remains an important public health problem, with classic risk factors being smoking and excessive alcohol consumption and usually has a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is important to explore the underlying mechanisms of tumorigenesis and screen the genes and pathways identified from such studies and their role in pathogenesis. The purpose of this study was to identify genes or signal pathways associated with the development of HNSC. Methods: In this study, we downloaded gene expression profiles of GSE53819 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including 18 HNSC tissues and 18 normal tissues. -

Original Article LIN28B Suppresses Microrna Let-7B Expression to Promote CD44+/LIN28B+ Human Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cell Proliferation and Invasion

Am J Cancer Res 2015;5(9):2643-2659 www.ajcr.us /ISSN:2156-6976/ajcr0008500 Original Article LIN28B suppresses microRNA let-7b expression to promote CD44+/LIN28B+ human pancreatic cancer stem cell proliferation and invasion Yebo Shao1*, Lei Zhang1*, Lei Cui2*, Wenhui Lou1, Dansong Wang1, Weiqi Lu1, Dayong Jin1, Te Liu3 1Department of General Surgery, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China; 2Department of General Surgery, Jiangsu University Affiliated Hospital, Zhengjiang 212000, China; 3Shanghai Geriatric Institute of Chinese Medicine, Longhua Hospital, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200031, China. *Equal contributors. Received March 27, 2015; Accepted July 5, 2015; Epub August 15, 2015; Published September 1, 2015 Abstract: Although the highly proliferative, migratory, and multi-drug resistant phenotype of human pancreatic can- cer stem cells (PCSCs) is well characterized, knowledge of their biological mechanisms is limited. We used CD44 and LIN28B as markers to screen, isolate, and enrich CSCs from human primary pancreatic cancer. Using flow cytometry, we identified a human primary pancreatic cancer cell (PCC) subpopulation expressing high levels of both CD44 and LIN28B. CD44+/LIN28B+ PCSCs expressed high levels of stemness marker genes and possessed higher migratory and invasive ability than CD44-/LIN28B- PCCs. CD44+/LIN28B+ PCSCs were more resistant to growth inhibition induced by the chemotherapeutic drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine hydrochloride, and readily established tumors in vivo in a relatively short time. Moreover, microarray analysis revealed significant differences between the cDNA expression patterns of CD44+/LIN28B+ PCSCs and CD44-/LIN28B- PCCs. Following siRNA interference of endogenous LIN28B gene expression in CD44+/LIN28B+ PCSCs, not only was their proliferation decreased, there was also cell cycle arrest due to suppression of cyclin D1 expression following the stimulation of miRNA let-7b expression. -

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Retinoic Acid Mediates Visceral-Specific

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA Retinoic Acid Mediates Visceral-specific Adipogenic Defects of Human Adipose-derived Stem Cells Kosuke Takeda, Sandhya Sriram, Xin Hui Derryn Chan, Wee Kiat Ong, Chia Rou Yeo, Betty Tan, Seung-Ah Lee, Kien Voon Kong, Shawn Hoon, Hongfeng Jiang, Jason J. Yuen, Jayakumar Perumal, Madhur Agrawal, Candida Vaz, Jimmy So, Asim Shabbir, William S. Blaner, Malini Olivo, Weiping Han, Vivek Tanavde, Sue-Anne Toh, and Shigeki Sugii Supplementary Experimental Procedures RNA-Seq experiment and analysis Total RNA was extracted from SC and VS fat depots using Qiagen RNeasy plus kit. Poly-A mRNA was then enriched from ~5 µg of total RNA with oligo dT beads (Life Technologies). Approximately 100 ng of poly-A mRNA recovered was used to construct multiplexed strand-specific RNA-seq libraries as per manufacturer’s instruction (NEXTflexTM Rapid Directional RNA-SEQ Kit (dUTP-Based) v2). Individual library quality was assessed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and quantified with a QuBit 2.0 fluorometer before pooling for sequencing on Illumina HiSeq 2000 (1x101 bp read). The pooled libraries were quantified using the KAPA quantification kit (KAPA Biosystems) prior to cluster formation. Fastq formatted reads were processed with Trimmomatic to remove adapter sequences and trim low quality bases (LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:36). Reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19) using Tophat version 2 (settings --no-coverage-search --library- type=fr-firststrand). Feature read counts were generated using htseq-count (Python package HTSeq default union-counting mode, strand=reverse). Differential Expression analysis was performed using the edgeR package in both ‘classic’ and generalized linear model (glm) modes to contrast SC and VS adipose tissues from 8 non-diabetic patients. -

C21orf62 CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmid (H): Sc-406451

SANTA CRUZ BIOTECHNOLOGY, INC. C21orf62 CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmid (h): sc-406451 BACKGROUND APPLICATIONS The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and C21orf62 CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmid (h) is recommended for the disruption of CRISPR-associated protein (Cas9) system is an adaptive immune response gene expression in human cells. defense mechanism used by archea and bacteria for the degradation of foreign genetic material (4,6). This mechanism can be repurposed for other 20 nt non-coding RNA sequence: guides Cas9 functions, including genomic engineering for mammalian systems, such as to a specific target location in the genomic DNA gene knockout (KO) (1,2,3,5). CRISPR/Cas9 KO Plasmid products enable the U6 promoter: drives gRNA scaffold: helps Cas9 identification and cleavage of specific genes by utilizing guide RNA (gRNA) expression of gRNA bind to target DNA sequences derived from the Genome-scale CRISPR Knock-Out (GeCKO) v2 library developed in the Zhang Laboratory at the Broad Institute (3,5). Termination signal Green Fluorescent Protein: to visually REFERENCES verify transfection CRISPR/Cas9 Knockout Plasmid CBh (chicken β-Actin 1. Cong, L., et al. 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas hybrid) promoter: drives systems. Science 339: 819-823. 2A peptide: expression of Cas9 allows production of both Cas9 and GFP from the 2. Mali, P., et al. 2013. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. same CBh promoter Science 339: 823-826. Nuclear localization signal 3. Ran, F.A., et al. 2013. Genome enginee ring using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nuclear localization signal SpCas9 ribonuclease Nat. Protoc. 8: 2281-2308. -

Supplementary Table S2. List of Genes with Expression That Is Positively Correlated (Pearson Correlation Coefficient P>0.3)

Supplementary Table S2. List of genes with expression that is positively correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient p>0.3) with HOXA9 expression in the study by Sun et al (1). Most HOXA genes (indicated by bold face) show highly significant positive correlation with HOXA9 expression, except for HOXA6 and HOXA13, similar to our findings in the UCSF and MDA tumor sets. Note that HOXA11, which did not demonstrate a statistically significant positive correlation with HOXA9 expression in both the UCSF and MDA tumor sets, demonstrates a substantially lower correlation coefficient relative to the other HOXA genes that positively correlate with HOXA9 expression in the study by Sun et al. These data were obtained from the online ONCOMINE database (www.oncomine.org) (2) searching for transcripts positively correlated with HOXA9 expression. Gene Name Gene Symbol Reporter ID Correlation (p) homeobox A9 HOXA9 214651_s_at .7682 homeobox A9 HOXA9 209905_at .7682 homeobox A10 HOXA10 213150_at .6058 homeobox A7 HOXA7 235753_at .6058 homeobox A10 HOXA10 213147_at .6058 homeobox A7 HOXA7 206847_s_at .6058 homeobox A4 HOXA4 206289_at .5741 homeobox A2 HOXA2 1557051_s_at .5379 homeobox A1 HOXA1 214639_s_at .5379 homeobox A3 HOXA3 235521_at .5379 homeobox B2 HOXB2 205453_at .5379 homeobox B3 HOXB3 228904_at .5379 EST EST 1555907_at .5379 homeobox A4 HOXA4 230080_at .5379 homeobox A2 HOXA2 228642_at .5379 homeobox A2 HOXA2 1557050_at .5379 homeobox A5 HOXA5 213844_at .5379 homeobox A2 HOXA2 214457_at .5113 homeobox B7 HOXB7 204778_x_at .5042 homeobox C6 HOXC6 -

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS and METHODS PBMC Transcriptomics

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS AND METHODS PBMC transcriptomics identifies immune-metabolism disorder during the development of HBV-ACLF Contents l Supplementary methods l Supplementary Figure 1 l Supplementary Figure 2 l Supplementary Figure 3 l Supplementary Figure 4 l Supplementary Figure 5 l Supplementary Table 1 l Supplementary Table 2 l Supplementary Table 3 l Supplementary Table 4 l Supplementary Tables 5-14 l Supplementary Table 15 l Supplementary Table 16 l Supplementary Table 17 Li J, et al. Gut 2021;0:1–13. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323395 BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS Test for HBV DNA The levels of HBV DNA were detected using real-time PCR with a COBAS® AmpliPrep/COBAS® TaqMan 48 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and HBV Test v2.0. Criteria for diagnosing cirrhosis Pathology The gold standard for the diagnosis of cirrhosis is a liver biopsy obtained through a percutaneous or transjugular approach.1 Ultrasonography was performed 2-4 hours before biopsy. Liver biopsy specimens were obtained by experienced physicians. Percutaneous transthoracic puncture of the liver was performed according to the standard criteria. After biopsy, patients were monitored in the hospital with periodic analyses of haematocrit and other vital signs for 24 hours. Cirrhosis was diagnosed according to the globally agreed upon criteria.2 Cirrhosis is defined based on its pathological features under a microscope: (a) the presence of parenchymal nodules, (b) differences in liver cell size and appearance, (c) fragmentation of the biopsy specimen, (d) fibrous septa, and (d) an altered architecture and vascular relationships. -

PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Prest Antigen C21orf62 Product Datasheet

PrEST Antigen C21orf62 Product Datasheet PrEST Antigen PRODUCT SPECIFICATION Product Name PrEST Antigen C21orf62 Product Number APrEST73914 Gene Description chromosome 21 open reading frame 62 Alternative Gene B37, C21orf120, PRED81 Names Corresponding Anti-C21orf62 (HPA016899) Antibodies Description Recombinant protein fragment of Human C21orf62 Amino Acid Sequence Recombinant Protein Epitope Signature Tag (PrEST) antigen sequence: TLVQDLKLSLCSTNTLPTEYLAICGLKRLRINMEAKHPFPEQSLLIHSGG DSDSREKPMWLHKGWQPCMYISFLD Fusion Tag N-terminal His6ABP (ABP = Albumin Binding Protein derived from Streptococcal Protein G) Expression Host E. coli Purification IMAC purification Predicted MW 26 kDa including tags Usage Suitable as control in WB and preadsorption assays using indicated corresponding antibodies. Purity >80% by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining Buffer PBS and 1M Urea, pH 7.4. Unit Size 100 µl Concentration Lot dependent Storage Upon delivery store at -20°C. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. Notes Gently mix before use. Optimal concentrations and conditions for each application should be determined by the user. Product of Sweden. For research use only. Not intended for pharmaceutical development, diagnostic, therapeutic or any in vivo use. No products from Atlas Antibodies may be resold, modified for resale or used to manufacture commercial products without prior written approval from Atlas Antibodies AB. Warranty: The products supplied by Atlas Antibodies are warranted to meet stated product specifications and to conform to label descriptions when used and stored properly. Unless otherwise stated, this warranty is limited to one year from date of sales for products used, handled and stored according to Atlas Antibodies AB's instructions. Atlas Antibodies AB's sole liability is limited to replacement of the product or refund of the purchase price. -

A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression

Supplementary Materials A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of High-LET Ionizing Radiations in Human Gene Expression Table S1. Statistically significant DEGs (Adj. p-value < 0.01) derived from meta-analysis for samples irradiated with high doses of HZE particles, collected 6-24 h post-IR not common with any other meta- analysis group. This meta-analysis group consists of 3 DEG lists obtained from DGEA, using a total of 11 control and 11 irradiated samples [Data Series: E-MTAB-5761 and E-MTAB-5754]. Ensembl ID Gene Symbol Gene Description Up-Regulated Genes ↑ (2425) ENSG00000000938 FGR FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase ENSG00000001036 FUCA2 alpha-L-fucosidase 2 ENSG00000001084 GCLC glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit ENSG00000001631 KRIT1 KRIT1 ankyrin repeat containing ENSG00000002079 MYH16 myosin heavy chain 16 pseudogene ENSG00000002587 HS3ST1 heparan sulfate-glucosamine 3-sulfotransferase 1 ENSG00000003056 M6PR mannose-6-phosphate receptor, cation dependent ENSG00000004059 ARF5 ADP ribosylation factor 5 ENSG00000004777 ARHGAP33 Rho GTPase activating protein 33 ENSG00000004799 PDK4 pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 ENSG00000004848 ARX aristaless related homeobox ENSG00000005022 SLC25A5 solute carrier family 25 member 5 ENSG00000005108 THSD7A thrombospondin type 1 domain containing 7A ENSG00000005194 CIAPIN1 cytokine induced apoptosis inhibitor 1 ENSG00000005381 MPO myeloperoxidase ENSG00000005486 RHBDD2 rhomboid domain containing 2 ENSG00000005884 ITGA3 integrin subunit alpha 3 ENSG00000006016 CRLF1 cytokine receptor like -

Table S1. 103 Ferroptosis-Related Genes Retrieved from the Genecards

Table S1. 103 ferroptosis-related genes retrieved from the GeneCards. Gene Symbol Description Category GPX4 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Protein Coding AIFM2 Apoptosis Inducing Factor Mitochondria Associated 2 Protein Coding TP53 Tumor Protein P53 Protein Coding ACSL4 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 4 Protein Coding SLC7A11 Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 Protein Coding VDAC2 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 2 Protein Coding VDAC3 Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 3 Protein Coding ATG5 Autophagy Related 5 Protein Coding ATG7 Autophagy Related 7 Protein Coding NCOA4 Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 4 Protein Coding HMOX1 Heme Oxygenase 1 Protein Coding SLC3A2 Solute Carrier Family 3 Member 2 Protein Coding ALOX15 Arachidonate 15-Lipoxygenase Protein Coding BECN1 Beclin 1 Protein Coding PRKAA1 Protein Kinase AMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha 1 Protein Coding SAT1 Spermidine/Spermine N1-Acetyltransferase 1 Protein Coding NF2 Neurofibromin 2 Protein Coding YAP1 Yes1 Associated Transcriptional Regulator Protein Coding FTH1 Ferritin Heavy Chain 1 Protein Coding TF Transferrin Protein Coding TFRC Transferrin Receptor Protein Coding FTL Ferritin Light Chain Protein Coding CYBB Cytochrome B-245 Beta Chain Protein Coding GSS Glutathione Synthetase Protein Coding CP Ceruloplasmin Protein Coding PRNP Prion Protein Protein Coding SLC11A2 Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2 Protein Coding SLC40A1 Solute Carrier Family 40 Member 1 Protein Coding STEAP3 STEAP3 Metalloreductase Protein Coding ACSL1 Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long Chain Family Member 1 Protein