MBA698 Beyond Budgeting at UBS Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

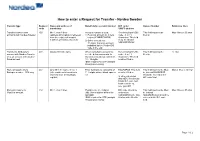

How to Enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden

How to enter a Request for Transfer - Nordea Sweden Transfer type Request Name and address of Beneficiary’s account number BIC code / Name of banker Reference lines code beneficiary SWIFT address Transfer between own 400 Min 1, max 4 lines Account number is used: Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be Max 4 lines x 35 char accounts with Nordea Sweden (address information is retrieved 1) Personal account no = pers code - 8 or 11 filled in from the register of account reg no (YYMMDDXXXX) characters. This field numbers of Nordea, Sweden) 2) Other account nos = must be filled in 11 digits. Currency account NDEASESSXXX indicated by the 3-letter ISO code in the end Transfer to third party’s 401 Always fill in the name When using bank account no., Receiving bank’s BIC This field must not be 12 char account with Nordea Sweden see the below comments. In code - 8 or 11 filled in or to an account with another Sweden account nos consist of characters. This field Swedish bank 10 - 15 digits. must be filled in IBAN required for STP (straight through processing) Domestic payments to 402 Only fill in the name in line 1 Enter bankgiro no consisting of BGABSESS. This field This field must not be filled Max 4 lines x 35 char Bankgiro number - SEK only (other address information is 7 - 8 digits without blank spaces must be filled in. in. Instead BGABSESS retrieved from the Bankgiro etc should be entered in the register) In other currencies BIC code field than SEK: Receivning banks BIC code and bank account no. -

Chronology, 1963–89

Chronology, 1963–89 This chronology covers key political and economic developments in the quarter century that saw the transformation of the Euromarkets into the world’s foremost financial markets. It also identifies milestones in the evolu- tion of Orion; transactions mentioned are those which were the first or the largest of their type or otherwise noteworthy. The tables and graphs present key financial and economic data of the era. Details of Orion’s financial his- tory are to be found in Appendix IV. Abbreviations: Chase (Chase Manhattan Bank), Royal (Royal Bank of Canada), NatPro (National Provincial Bank), Westminster (Westminster Bank), NatWest (National Westminster Bank), WestLB (Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale), Mitsubishi (Mitsubishi Bank) and Orion (for Orion Bank, Orion Termbank, Orion Royal Bank and subsidiaries). Under Orion financings: ‘loans’ are syndicated loans, NIFs, RUFs etc.; ‘bonds’ are public issues, private placements, FRNs, FRCDs and other secu- rities, lead managed, co-managed, managed or advised by Orion. New loan transactions and new bond transactions are intended to show the range of Orion’s client base and refer to clients not previously mentioned. The word ‘subsequently’ in brackets indicates subsequent transactions of the same type and for the same client. Transaction amounts expressed in US dollars some- times include non-dollar transactions, converted at the prevailing rates of exchange. 1963 Global events Feb Canadian Conservative government falls. Apr Lester Pearson Premier. Mar China and Pakistan settle border dispute. May Jomo Kenyatta Premier of Kenya. Organization of African Unity formed, after widespread decolonization. Jun Election of Pope Paul VI. Aug Test Ban Take Your Partners Treaty. -

Svenska Handelsbanken AB

OFFERING CIRCULAR Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (Incorporated as a public limited liability banking company in The Kingdom of Sweden) U.S.$50,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme for the issue of Notes with a minimum maturity of one month On 26th June, 1992 Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (the “Issuer” or the “Bank”) entered into a U.S.$1,500,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme (the “Programme”) and issued an offering circular on that date describing the Programme. This Offering Circular supersedes any previous offering circular and supplements therein prepared in connection with the Programme. Any Notes (as defined below) issued under the Programme on or after the date of this Offering Circular are issued subject to the provisions described herein. This does not affect any Notes already in issue. Under the Programme, the Bank may from time to time issue Notes (the “Notes”), which expression shall include Notes (i) issued on a senior preferred basis as described in Condition 3 (“Senior Preferred Notes”), (ii) issued on a senior non-preferred basis as described in Condition 4 (“Senior Non-Preferred Notes”), (iii) issued on a subordinated basis and which rank on any voluntary or involuntary liquidation (Sw. likvidation) or bankruptcy (Sw. konkurs) of the Bank as described in Condition 5 (“Subordinated Notes”) and (iv) issued on a subordinated basis with no fixed maturity and which rank on any voluntary or involuntary liquidation (Sw. likvidation) or bankruptcy (Sw. konkurs) of the Bank as described in Condition 6 (“Additional Tier 1 Notes”). The Outstanding Principal Amount (as defined in Condition 2) of each Series (as defined below) of Additional Tier 1 Notes will be subject to Write Down (as defined in Condition 2) if the Common Equity Tier 1 Capital Ratio (as defined in Condition 2) of the Bank and/or the Handelsbanken Group (as defined Condition 2) is less than the relevant Trigger Level (as defined in Condition 2). -

Interim Report January – September 2020 Q3

Interim Report January – September 2020 Q3 Financial summary Third quarter First nine months • Net sales amounted to EUR 27k (0) • Net sales amounted to EUR 126k (21k) • Operating loss (EBIT) increased to EUR 4,790k • Operating loss (EBIT) increased to EUR 7,291k (748k) driven by listing costs (3,490k) driven by listing costs • Loss after tax amounted to EUR 4,730k (815k) • Loss after tax amounted to EUR 7,127k (3,602k) • Basic and diluted loss per Class A share amounted to EUR 0.10 (0.02) • Basic and diluted loss per Class A share amounted to EUR 0.16 (0.08) • Liquid funds as at end of the period amounted to EUR 90.5m • Cash flow from operating activities amounted to EUR -1,824k (-3,014k) • No interest-bearing debt at end of the period Figures within parentheses refer to the preceding year. Significant events • Enlisted Inselspital Bern, the largest In the third quarter of 2020 university hospital in Switzerland, to be the lead hospital in our upcoming RefluxStop™ • Completed listing on Nasdaq First North Premier Growth Market raising SEK 1.1 Registry clinical trial to be focused primarily billion, with trading of Implantica's Swedish in Germany and Switzerland. Depository Receipts commencing on September 21, 2020. The offering was After the end of the period substantially oversubscribed. • Exercised overallotment option raising an additional SEK 165 million. • Increased our shareholder base with highly reputable shareholders such as Swedbank • Implantica’s RefluxStop™ trial showed Robur Ny Teknik, Handelsbanken Fonder, exceptional three-year follow-up results. TIN Fonder, Skandia and Nordea Investment None of the 47 patients in the study were in Management. -

Svenska Handelsbanken

Annual Report 2001 Svenska Handelsbanken THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF SVENSKA HANDELSBANKEN will be held at the Grand Hôtel, Vinterträdgården, Royal entrance, Stallgatan 4, Stockholm, at 10.00 a.m. on Tuesday, 23 April 2002. NOTICE OF ATTENDANCE AT ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Shareholders wishing to attend the Meeting must: • be entered in the Register of Shareholders kept by VPC AB (Swedish Central Securities Depository and Clearing Organisation), on or before Friday, 12 April 2002, and • give notice of attendance to the Chairman's Office at the Head Office of the Bank, Kungsträdgårdsgatan 2, SE-106 70 Stockholm, telephone +46 8 701 19 84, or via the Internet www.handelsbanken.se/bolagsstamma (Swedish only), by 3 p.m. on Wednesday, 17 April 2002. In order to be entitled to take part in the Meeting, any share- holders whose shares are nominee-registered must also request a temporary entry in the register of shareholders kept by the VPC. Shareholders must notify the nominee about this well before 12 April 2002, when this entry must have been effected. DIVIDEND The Board of Directors recommends that the record day for the dividend be Friday, 26 April 2002. If the Annual General Meeting votes in accordance with this recommendation, the VPC expects to be able to send the dividend to shareholders on Thursday, 2 May 2002. PUBLICATION DATES FOR INTERIM REPORTS January–March 22 April 2002 January–June 20 August 2002 January–September 22 October 2002 Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) Registered no. 502007-7862 www.handelsbanken.se Contents HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR 2 THE GROUP CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S COMMENTS.......... -

List of PRA-Regulated Banks

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 2nd December 2019 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 31st October 2019 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The ADIB (UK) Ltd EFG Private Bank Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC Europe Arab Bank plc AIB Group (UK) Plc Al Rayan Bank PLC FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Aldermore Bank Plc FCE Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Allica Bank Ltd Alpha Bank London Limited Gatehouse Bank Plc Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Ghana International Bank Plc Atom Bank PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Axis Bank UK Limited Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank and Clients PLC Bank Leumi (UK) plc Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Hampden & Co Plc Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Handelsbanken PLC Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Havin Bank Ltd Bank of China (UK) Ltd HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of London and The Middle East plc HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank of Scotland plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC Bank Saderat Plc ICBC (London) plc Bank Sepah International Plc ICBC Standard Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc ICICI Bank UK Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC Investec Bank PLC BFC Bank Limited Itau BBA International PLC Bira Bank Limited BMCE Bank International plc J.P. -

Handelsbanken Ulf Riese, CFO

Handelsbanken Ulf Riese, CFO Morgan Stanley European Financials Conference 2 April 2009 Handelsbanken Financial target – focus on profitability Handelsbanken’s financial goal is to have a higher return on equity than a weighted average of comparable listed Nordic and British banks This should be achieved through: More satisfied clients Lower costs than peers The financial goal has been reached for 37 consecutive years 2 Handelsbanken Higher profitability than the average for comparable banks Return on shareholder’s equity, 1973 - 2008 % Handelsbanken Other Comparable banks* 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 -5 1973 1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 2008 Return on shareholder's equity after standard tax. * Since 2003 the comparable banks are: SEB, Nordea, Swedbank, Danske Bank samt DnB NOR. 3 Handelsbanken Business model Decentralisation Nonnegotiable Credit policy No central No bonus Business control system marketing Responsibility and Accountability Customer The branch No budget is the bank 4 Handelsbanken We have more satisfied customers Customer satisfaction – private customers Handelsbanken Sector average, weighted Index Sweden Index Denmark 80 85 75 80 70 75 70 65 65 60 60 55 55 50 50 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Index Finland Index Norway 85 75 80 70 75 70 65 65 60 60 55 55 50 50 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2002 / 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Source: SKI, Dansk KundeIndex, EPSI Rating and EPSI Norway. 2003 5 In Sweden, the sector average comprises SEB, Nordea and Swedbank. Handelsbanken We are the most cost-effective bank Cost/income-ratio before loan losses, Jan – Dec 2008 Weighted average % excl. -

Day One: March 24Th

Day One: March 24th 09:00 FinTech Network Welcome: Hannah Kitchen, Conference Organiser 09:15 Chairperson’s Introduction & Welcome: Graham Cressey, Open Data Stream Lead, FinTech Innovation Lab, Accenture 09:30 Open Banking and Digital Ecosystems: BBVA's key learnings. • Explore digital ecosystems as one of the key points for the connection and relationship between consumers and service providers today • Discuss if the need for financial services is efficiently met and how to improve current inefficiencies • Analyse how Open banking is an enabler of these relationships and the new opportunities it brings for innovation and growth Ana Climente, Head of Open Banking Spain, BBVA 10:00 Leveraging the Core Values of your Business Model in an Open Banking Environment • Gain insight on the methods Handelsbanken is employing to integrate an open value chain into their existing unique business model • Learn why Handelbanken’s branches are a key component of creating an open value chain and how they ensure synergy between branches and corporate strategies • Hear Handlesbanken’s case study on how collaboration is a key element for creating a business model fit for the 2020 open banking landscape Malin Lignell, Digitalisation and Innovation, Handelsbanken 10:30 Panel Discussion: Driving Open Banking Forward – Regulatory Guidance • Review recent regulatory activity relating to open banking and hear an overview of expected future developments to ensure your compliance strategies align • Discuss collaboration between banks and regulators to understand -

Scandic Publishes a Supplement to the Prospectus Regarding the Rights Issue

Not for release, publication or distribution in Australia, Canada, Japan or the United States. These materials are not an offer for sale of securities in the United States. Securities may not be sold in the United States absent registration with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or an exemption from registration under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended. The issuer of the securities does not intend to register any part of the offering in the United States or to conduct a public offering of the rights or the shares in the United States. PRESS RELEASE June 10, 2020 Scandic publishes a supplement to the prospectus regarding the rights issue Scandic Hotels Group AB (publ) (“Scandic” or the “Company”) today publish a supplement (the “Supplement”) to the prospectus regarding Scandic’s rights issue (the “Rights Issue”) that was approved by the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority (the “SFSA”) and published on 1 June, 2020 (the “Prospectus”). The Supplement forms a part of, and must be read together with, the Prospectus. The Supplement has been prepared by reason of Scandic on 8 June, 2020, through a press release, publishing information concerning Scandic’s occupancy and booking levels. The Supplement has been prepared in accordance with article 23 of regulation (EU) 2017/1129 (the “Prospectus Regulation”) and was approved and registered by the SFSA on 10 June, 2020 (SFSA’s registration number 20-13770). The Supplement and all other information relating to the Rights Issue is available on the Company’s website www.scandichotelsgroup.com. The Supplement is also available on Handelsbanken’s website, www.handelsbanken.se/prospekt, DNB’s website www.dnb.no/emisjoner and Nordea’s website www.nordea.se/prospekt. -

Handelsbanken UK Risks Low Costs

Low credit Handelsbanken UK risks Low costs Local Satisfied Investor Presentation responsibility customers Nomura Conference SHB’s 21 November 2013 market Anders Bouvin, CEO UK Martin Blåvarg, Head of UK & US IR Handelsbanken’ s strengths . For the ppyast 41 years, the bank has had higgpher profitability than the average of its competitors . Since the first indeppyendent survey was made in 1989, Handelsbanken has had the highest level of customer satisfaction of the four largest banks in Sweden . For manyyy years, Handelsbanken has been one of the most cost-efficient universal banks in Europe with . lower administrative costs . lower loan losses . lower funding cost 2 Handelsbanken has six home markets Sweden 461 branches Norway 49 branches Finland 45 branches Denmark 55 branches Great Britain 166 branches * The Netherlands 16 branches * Per 6 November 2013, including recruited branch managers. Outside its home markets, the bank has operations in 28 locations in 18 countries : Branches: Representative offices: USA (New York) Poland (Warsaw) Beijing Sydney Singgpapore Austria (()Vienna) Kuala Lumpur Taipei Germany Estonia (Tallinn) Marbella Zürich France (Paris, Nice) Latvia (Riga) Moscow Greater China (Hong Kong, Shanghai) Lithuania (Vilnius) Mumbai Luxembourg São Paolo 3 Unchanged business model for 41 years Financial goal – focus on profitability To have a higher return on equity than a weighted average of comparable peers This goal has been reached for the last 41 consecutive years Decentralisation Non-negotiable . Credit policy The branch is the bank No bonus . Business control system . Responsibility and Accountability Customer Other key features . Focus on profitability – not volumes . Organic growth No central No budget marketing . -

CREDIT RESEARCH June 4, 2021, 11:31 CET Real Estate | Sweden

[3,533 CREDIT RESEARCH June 4, 2021, 11:31 CET Real Estate | Sweden Diös No recommendation Heading for the Northern Lights MARKETING COMMUNICATION . A leader in stable and growing cities of northern Sweden . Strengthening credit profile . Handelsbanken has a mandate to issue bonds for Diös Leading market position in a growing, dynamic region Diös Fastigheter AB (Diös) has a market-leading position in 10 larger, growing cities in northern Sweden, as well as in Gävleborg County and Dalarna County. In our view, its property portfolio is well-diversified in terms of regional presence, property types and tenants, of which around 31% are related to government and municipalities, and 8% are residential rental properties. Based on data from Statistics Sweden and the regional municipalities, we expect the markets where Diös is active to continue to show healthy population and economic growth, which should in turn support the local property markets. About the company Strengthening credit profile We expect Diös to continue to strengthen its credit profile, including a sustained Profile: LTV of less than 55%, a lengthening of the debt maturity profile and an increased Diös Fastigheter AB, owns, manages and develops share of unsecured capital markets funding. Thanks to its cash-generative property commercial and residential properties, primarily in the larger cities of northern Sweden. The company was portfolio, we find that Diös’ credit metrics, such as debt-to-EBITDA and interest founded in 2005 and is headquartered in Östersund. coverage, are typically stronger than many of its Swedish real estate peers’. Total assets amounted to SEK 25bn as of March 31, 2021. -

Supplementary Offering Circular Dated 27Th April, 2018

SUPPLEMENTARY OFFERING CIRCULAR DATED 27TH APRIL, 2018 Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (Incorporated as a public limited liability banking company in The Kingdom of Sweden) U.S.$50,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme This Supplementary Offering Circular (the Supplement) to the Offering Circular (the Offering Circular) dated 19th June, 2017, which, together with the Supplementary Offering Circular dated 20th July, 2017 (the First Supplement), the Supplementary Offering Circular dated 23rd October, 2017 (the Second Supplement), the Supplementary Offering Circular dated 12th February, 2018 (the Third Supplement) and the Supplementary Offering Circular dated 19th February, 2018 (the Fourth Supplement), comprises a base prospectus and is prepared in connection with the Euro Medium Term Note Programme established by Svenska Handelsbanken AB (publ) (the Issuer). This Supplement constitutes a supplementary prospectus for the purposes of Article 16 of Directive 2003/71/EC as amended (the Prospectus Directive) as implemented in Ireland by the Prospectus (Directive 2003/71/EC) Regulations 2005 and is prepared in order to update the Offering Circular. Terms defined in the Offering Circular have the same meaning when used in this Supplement. This Supplement is supplemental to, and should be read in conjunction with, the Offering Circular and any other supplements to the Offering Circular issued by the Issuer. This Supplement has been approved by the Central Bank of Ireland, as competent authority under the Prospectus Directive. The Central Bank of Ireland only approves this Supplement as meeting the requirements imposed under Irish and EU law pursuant to the Prospectus Directive. The Issuer accepts responsibility for the information contained in this Supplement.