The Spatial Eld of Plots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Corel Ventura

Anthropology / Middle East / World Music Goodman BERBER “Sure to interest a number of different audiences, BERBER from language and music scholars to specialists on North Africa. [A] superb book, clearly written, CULTURE analytically incisive, about very important issues that have not been described elsewhere.” ON THE —John Bowen, Washington University CULTURE WORLD STAGE In this nuanced study of the performance of cultural identity, Jane E. Goodman travels from contemporary Kabyle Berber communities in Algeria and France to the colonial archives, identifying the products, performances, and media through which Berber identity has developed. ON In the 1990s, with a major Islamist insurgency underway in Algeria, Berber cultural associations created performance forms that challenged THE Islamist premises while critiquing their own village practices. Goodman describes the phenomenon of new Kabyle song, a form of world music that transformed village songs for global audiences. WORLD She follows new songs as they move from their producers to the copyright agency to the Parisian stage, highlighting the networks of circulation and exchange through which Berbers have achieved From Village global visibility. to Video STAGE JANE E. GOODMAN is Associate Professor of Communication and Culture at Indiana University. While training to become a cultural anthropologist, she performed with the women’s world music group Libana. Cover photographs: Yamina Djouadou, Algeria, 1993, by Jane E. Goodman. Textile photograph by Michael Cavanagh. The textile is from a Berber women’s fuda, or outer-skirt. Jane E. Goodman http://iupress.indiana.edu 1-800-842-6796 INDIANA Berber Culture on the World Stage JANE E. GOODMAN Berber Culture on the World Stage From Village to Video indiana university press Bloomington and Indianapolis This book is a publication of Indiana University Press 601 North Morton Street Bloomington, IN 47404-3797 USA http://iupress.indiana.edu Telephone orders 800-842-6796 Fax orders 812-855-7931 Orders by e-mail [email protected] © 2005 by Jane E. -

Felucca Letter-CC - Google Docs

1/14/2019 Felucca Letter-CC - Google Docs January 14, 2019 Dear Blank, I just got back from an amazing trip to Egypt. I took sixty students along with me. Man, what a nightmare getting everyone a passport and the proper shots. We took a 747 out of SFO, that’s San Francisco International Airport, and the flight took over TWENTY hours, twelve to London, a four hour lay over, then another four hours to Cairo. When we finally got to our hotel we were so tired we didn’t notice how nice it actually was. We spent three nights in the Four Season Cairo at the Nile. What a spectacular hotel! The pool is amazing with four hot tubs and a swim up bar. Of course, Mrs. M and I couldn’t enjoy the bar, except for a soda, as we were traveling with 60 rambunctious sixth graders, but...maybe next time. Most incredible though was finally visiting all the sites I been teaching my students about for the past 28 years. Finally, I got to see Khufu’s Great Pyramid at Giza and the impressive monument to Ramses II at Abu Simbel. But, my two favorite sites are actually less wellknown. Both Hatshepsut’s temple at DayralBahri and Senusret’s White Chapel have amazing stories behind their construction. My favorite site was Hatshepsut's temple at DayralBahri. Hatshepsut was the first really powerful female pharaoh. She loved to be viewed as a man, and often wore a false beard, the symbol of divine kingship. -

Nile Serenity Felucca Sailing on the Nile

Nile Serenity Sunset Canapés Felucca Felucca Sailing on the Nile $37/person English Cheddar Cheese & Pickles, Baguette Smoked Chicken Breast & Sweet Mango Relish Smoked Salmon & Capers, Whole Wheat Bread Smoked Beef & Oriental Pickles Smoked Turkey, Sun Dry Tomato On Rye Bread Feta Cheese, Olives & Cucumber, Shammi Inclusive of one soft drink and water Beverages Bellini Cocktail LE 280 / Drink Champagne & Sparkling Moet & Chandon, 0.75l LE 5345 Valmont Cuvée Aida White 0.75l LE 760 Experience Felucca sailing from the Hilton promenade. Valmont Cuvée Aida Rose 0.75l LE 760 Choice of timings available, with a selection of catering options Omar Khayyam, Egypt 0.75l LE 677 White/Red wine Sailings* Cape Bay, Okay , 0.75l LE 933 7 am to 5 pm South Africa. * Sailing timing may change as per local regulations White/Red wine Price is inclusive of Vat & Service chare Price is inclusive of Vat & Service chare Minimum charge of 2 persons per felucca Minimum charge of 2 persons per felucca Breakfast Felucca Lunch Felucca Continental Breakfast Felucca Continental Menu Felucca $25 /person $40 /person Fresh Orange Juice Hand Picked Local Rocket Leaves Fresh Seasonal Fruit Salad Roast Vegetables, Feta Cheese & Balsamic Dressing Baker’s Basket Fresh Baked Breads and Arabic Bread Butter Butter & Preserves *** Coffee Family Style Herb Roast Chicken Herb Mash Potates, Seasonal Vegetables **************************** Full Breakfast Felucca Porcini Mushroom Sauce $35 /person *** Orange Juice Walnut Brownies Yoghurt Seasonal Fruits Cheese and Cold Cut Platter -

Make a Boat for the Nile

Make a boat for the Nile The Nile was Egypt’s highway. There weren’t any roads or bridges in Egypt so boats were used for transport. Everything including mummies could be carried in them. The first boats were made from reeds or papyrus and these were commonly used in the shallow marshy water. They were called feluccas. Here’s how to make a felucca just like the ancient Egyptians. Materials you need • One bunch of straw cut to 30 cm • Bamboo skewers lengths • Optional square of linen or canvas • String • Plasticine or modelling clay • Glue Method Step 1 Make up three bundles of straw to two centimetres thickness each. Tie each bundle separately at both ends. Cut one bundle in half so you have two 15 centimetre lengths. Tie the loose ends together. Place the shorter bundles firmly together and tie at the top and the bottom again. This will become the base of the boat. Step 2 Take the two long bundles and tie them together at one end. Wedge the shorter bundles between the longer ones, pushing them firmly together. Put ties across the boat at two centimetre intervals all the way to the end to hold securely. Step 3 Attach a string to one end of the boat, thread it through the middle tie and loop it around the other end. Pull the string to make your boat curve. Secure the other end when you have the shape you want. Make an oar by cutting a bamboo skewer in half and decorating with a blob of plasticine or modelling clay. -

Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~

2 Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~/. MODEL SHIPWAYS Marine Model Co. YOUNG AMERICA #1079 SEA WITCH Marine Model Co. Extreme Clipper Ship (Clipper Ship) New York, 1853 #1 084 SWORDFISH First of the famous Clippers, built in (Medium Clipper Ship) LENGTH 21"-HEIGHT 13\4" 1846, she had an exciting career and OUR MODEL DEPARTMENT • • • Designed and built in 1851, her rec SCALE f."= I Ft. holds a unique place in the history Stocked from keel to topmast with ship model kits. Hulls of sailing vessels. ord passage from New York to San of finest carved wood, of plastic, of moulded wood. Plans and instructions -··········-·············· $ 1.00 Francisco in 91 days was eclipsed Scale 1/8" = I ft. Models for youthful builders as well as experienced mplete kit --·----- $10o25 only once. She also engaged in professionals. Length & height 36" x 24 " Mahogany hull optional. Plan only, $4.QO China Sea trade and made many Price complete as illustrated with mahogany Come a:r:1d see us if you can - or send your orders and passages to Canton. be assured of our genuine personal interest in your Add $1.00 to above price. hull and baseboard . Brass pedestals . $49,95 selection. Scale 3/32" = I ft. Hull only, on 3"t" scale, $11.50 Length & height 23" x 15" ~LISS Plan only, $1.50 & CO., INC. Price complete as illustrated with mahogany hull and baseboard. Brass pedestals. POSTAL INSTRUCTIONS $27.95 7. Returns for exchange or refund must be made within 1. Add :Jrt postage to all orders under $1 .00 for Boston 10 days. -

8Th National Summit on Coastal & Estuarine Restoration and 25Th

8th National Summit on Coastal & Estuarine Restoration and 25th Biennial Meeting of The Coastal Society Hilton New Orleans Riverside December 12, 2016 11:00 – 12:30 THE PISCINE GEOGRAPHY OF COASTAL AND ESTUARINE HABITATS – Don Davis, Louisiana Sea Grant College Program A Working Coast is a landscape of “Invisible” People, particularly from a historical perspective. The Human Mosaic English Vietnamese Portuguese Lebanese Norwegians Danes Swedes Americans Scots Poles Malays French Filipinos Spanish Laotian Chinese Austrians/ Italians Yugoslavians Germans Cajuns Greeks Isleños Irish African Latin American Americans Native Americans Tri-Racial Jews Groups THE LABOR FORCE “I enclose the receipts for advances to the oyster shuckers. I understand that advances to tenants come back out of the crops which the tenants make, and the advances to boats come back out of the oysters which the boats catch, and that this means that although we pay 40¢ or 45¢ or even 50¢ for oysters delivered at the factory, we take out of this money which we pay for the oysters the amounts due from the several boats respectively. .” Joseph S. Clark, Sr., Philadelphia, Pa., to E. A. McIlhenny, Avery Island, La., 26 December 1908, TLS. Bohemians from Baltimore Image courtesy of the McIlhenny Company Archives, Avery Island, La. WOMEN WERE THE BACKBONE OF THE FISHERY’S LABOR FORCE CHILD LABOR LEWIS HINES Bluffton, SC, ca. 1913 Bayou LaBatre, AL, ca. 1912 Biloxi, MS, ca. 1911 Dunbar & Dukate, New Orleans, LA, Alabama Canning Co., ca 1910 ca. 1911 Work in canneries was originally -

MEREKEELE NÕUKOJA Koosoleku Teokiri Nr 80 09.04.2013 Veeteede

MEREKEELE NÕUKOJA Koosoleku teokiri nr 80 09.04.2013 Veeteede Amet Tallinn, Valge tn 4 Algus kell 14.00, lõpp 16.00 Osavõtjad: Malle Hunt, Peedu Kass, Uno Laur, Taidus Linikoja, Aado Luksepp, Ants Raud, Rein Raudsalu, Tauri Roosipuu, Madli Vitismann, Peeter Veegen, Ants Ärsis. Juhataja: Peedu Kass Kirjutaja: Malle Hunt 1. Mälestasime leinaseisakuga meie seast lahkunud nõukoja liiget Ain Eidastit. 2. Vastasime terminoloogi küsimustele. Pikem selgitus terminitele port ja harbour Peeter Veegen: Meil Tallinnas on "Port of Tallinn" administratiiv-juriidiline ettevõte, mille koosseisus mitu väiksemat sadamat, mida võime tõlkida "harbour" (Paljassaare Harbour, Old Harbour, Paldiski Harbour). Ajalooliselt on pigemini kujunenud nii, et Harbour on varjumis- ja seismise koht laevadele, millel võib olla erinevaid funktsioone (nt. Miinisadam, Lennusadam, Hüdrograafiasadam jne.) Ehk ka "Last harbour" - viimne varjupaik. Port on seevastu kauba käitlemise, lastimise-lossimise, reisijate teenendamise koht- teiste sõnadega ühendus maa ja mere vahel (ka arvutil on mitu "porti" ühenduseks maailmaga). Merekaubavedudel kasutame mõisted "Port of call", "Port of destination" Vene keelest leiame analoogiana gavanj = harbour, port = port Eesti keeles on meil mõlemal juhul sadam, nii et neid kattuvaid mõisteid võime kasutada nii ja naa, aga kontekstist lähtuvalt võiks siiski tõlkes ajaloolist tausta arvestada. Madli Vitismann: - "port" on enam ettevõte, terminalide kogum ja muu lastimisega seotu - sadamaettevõtted Port of Tallinn ja Ports of Stockholm (samuti mitut sadamat koondav ettevõte). Või Paldiski Northern Port kui omaette sadamaettevõte. - "harbour" on pigem sadam kui konkreetne sadamabassein, sildumiskoht jm, nt Old City harbour Tallinna Sadama koosseisus ja Kapellskär Stockholmi Sadamate koosseisus - nende kodulehel on rubriik "Ship in harbour" http://www.stockholmshamnar.se/en/ . Ka rootsi keeles on üks vaste sõnale "sadam" - "hamn". -

5030 Roosevelt Way NE, Seattle WA 98105 (206) 524-8554 * BLOG.SCARECROW.COM Page 1 of 8

Films referenced in JOURNEYS THROUGH FRENCH CINEMA which you can rent from Scarecrow Video EPISODE 1 AU GRAND BALCON - Henri Decoin, 1949 In section: Foreign - France BATTEMENT DE COEUR (BEATING HEART) - Henri Decoin, 1940 In section: Foreign - France DAINAH LA METISSE - Jean Gremillon, 1932 In section: Foreign - France EARRINGS OF MADAME DE… - Max Ophuls, 1953 In section: Directors - Max Ophuls LA RONDE - Max Ophuls, 1950 In section: Directors - Max Ophuls LA VERITE SUR BEBE DONGE (THE TRUTH ABOUT BEBE DONGE) - Henri Decoin, 1952 In section: Foreign - France L'AMOUR D'UNE FEMME (THE LOVE OF A WOMAN) - Jean Gremillon, 1953 In section: Foreign - France LE CIEL EST A VOUS - Jean Gremillon, 1944 In section: Foreign - France LE PLAISIR - Max Ophuls, 1952 In section: Directors - Max Ophuls LES AMOREUX SONT SEULS AU MONDE (MONELLE) - Henri Decoin, 1948 In section: Foreign - France LES INCONNUS DANS LA MAISON (STRANGERS IN THE HOUSE) - Henri Decoin, 1942 In section: Foreign - France LOLA MONTES - Max Ophuls, 1955 In section: Directors - Max Ophuls LUMIERE D'ETE - Jean Gremillon, 1943 In section: Foreign - France PATTES BLANCHES (WHITE PAWS) - Jean Gremillon, 1949 In section: Foreign - France RAZZIA SUR LA CHNOUF - Henri Decoin, 1955 In section: Foreign - France REMORQUES (STORMY WATERS) - Jean Gremillon, 1941 In section: Foreign - France EPISODE 2 ANGELE - Marcel Pagnol, 1934 In section: Literature - Marcel Pagnol 5030 Roosevelt Way NE, Seattle WA 98105 (206) 524-8554 * BLOG.SCARECROW.COM Page 1 of 8 Films referenced in JOURNEYS THROUGH FRENCH CINEMA which you can rent from Scarecrow Video ANTOINE ET ANTOINETTE - Jacques Becker, 1947 In section: Directors - Jacques Becker AU HASARD BALTHAZAR - Robert Bresson, 1966 In section: Directors - Robert Bresson DESIRE - Sacha Guitry, 1937 In section: Foreign - France FAISONS UN RĘVE.. -

Sailing Alone Around the World by Joshua Slocum

Project Gutenberg's Sailing Alone Around The World, by Joshua Slocum This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Sailing Alone Around The World Author: Joshua Slocum Illustrator: Thomas Fogarty George Varian Posting Date: October 12, 2010 Release Date: August, 2004 [EBook #6317] [This file was first posted on November 25, 2002] [Last updated: August 16, 2012] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD *** Produced by D Garcia, Juliet Sutherland, Charles Franks HTML version produced by Chuck Greif. SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD The "Spray" from a photograph taken in Australian waters. SAILING ALONE AROUND THE WORLD By Captain Joshua Slocum Illustrated by THOMAS FOGARTY AND GEORGE VARIAN TO THE ONE WHO SAID: "THE 'SPRAY' WILL COME BACK." CONTENTS CHAPTER I A blue-nose ancestry with Yankee proclivities—Youthful fondness for the sea—Master of the ship Northern Light—Loss of the Aquidneck—Return home from Brazil in the canoe Liberdade—The gift of a "ship"—The rebuilding of the Spray—Conundrums in regard to finance and calking—The launching of the Spray. CHAPTER II Failure as a fisherman—A voyage around the world projected—From Boston to Gloucester—Fitting out for the ocean voyage—Half of a dory for a ship's boat—The run from Gloucester to Nova Scotia—A shaking up in home waters—Among old friends. -

Legends of the Nile Featuring Abu Simbel

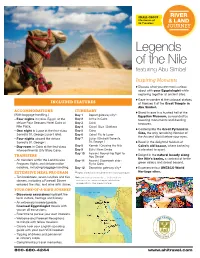

SMALL GROUP RIVER Ma xi mum of 28 Travele rs & LAND JO URNEY Legends of the Nile featuring Abu Simbel Inspiring Moments >Discuss what you are most curious about with your Egyptologist while exploring together at ancient sites. >Gaze in wonder at the colossal statues INCLUDED FEATURES of Ramses II at the Great Temple in Abu Simbel. ACCOMMODATIONS ITINERARY > A Stand in awe in a hushed hall of the (With baggage handling.) Day 1 Depart gateway city Egyptian Museum, surrounded by – Four nights in Cairo, Egypt, at the Day 2 Arrive in Cairo towering monuments and dazzling deluxe Four Seasons Hotel Cairo at Day 3 Cairo treasures. Nile Plaza. Day 4 Cairo | Giza | Sakkara >Contemplate the Great Pyramid in – One night in Luxor at the first-class Day 5 Cairo Giza, the only remaining Wonder of Sonesta St. George Luxor Hotel. Day 6 Cairo | Fly to Luxor the Ancient World before your eyes. – Four nights aboard the deluxe Day 7 Luxor | Embark Sonesta Sonesta St. George I. St. George I >Revel in the delightful hubbub of – Day room in Cairo at the first-class Day 8 Karnak | Cruising the Nile Cairo’s old bazaar, where bartering Intercontinental City Stars Cairo. Day 9 Edfu | Kom Ombo is elevated to sport. Day 10 Aswan | Round-trip flight to >Delight in the natural beauty along TRANSFERS Abu Simbel the Nile’s banks, a contrast of fertile – All transfers within the Land/Cruise Day 11 Aswan | Disembark ship | Program: flights and deluxe motor Fly to Cairo green valleys and desert beyond. coaches, including baggage handling. -

Cairo Layover Tours Visit Pyramid of Giza and Felucca Ride on the Nile

Cairo Layover Tours Visit Pyramid of Giza And Felucca Ride on The Nile From Cairo Airport Starts as per requested time Pickup from Cairo airport by our Local Tour guide who will be Holding a sign shows your name on it then Transfer in Private A/C Limousine to Giza City to to Giza area where you Visit the Famous Pyramid of Egypt which is Known as Giza PyramidsVisit the Great Pyramid of King Cheops,Visit the Middle Pyramid of King Chephern also there is Possibilities to enter any of the Pyramids from inside But this Requires additional Tickets can be Bought on Spot and our guide will assist you in that matter .Then Visit the Sphinx Statue one of the Oldest and Biggest Sphinx in ancient Egypt Then Drive from Giza to Cairo City Center where you can Enjoy the Nile Trip on the Nile in Cairo and getting on one of the traditional Egyptian Boat that Known as the Felucca Ride Enjoy an hour sailing on the Nile and after the ride you will be transferred Back to Cairo airport Private Guided Tour includes all transfers,Entry Fees,Tour guide Water and Snacks Excludes entry inside the Pyramid or Camel Ride but can be arranged on Spot HIGHLIGHTS Visit the Great Pyramids at Giza Professional Photos will be taken by our guide Visit the great Sphinx at Giza Entry Fees Expert Tour guide All Taxes Services Bottle of Water All Transfers by Private A/C Latest Model Vehicle Tipping Insid the pyramids .