Christian Monastic Communities Living in Harmony with the Environment: an Overview of Positive Trends and Best Practices 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divinity School 2013–2014

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2013–2014 Divinity School Divinity 2013–2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 3 June 20, 2013 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849. -

Hunston Convent and Its Reuse As Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North R North- at - Fastmail.Net 25 April 2017

Hunston Convent and its reuse as Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North r_north- at - fastmail.net 25 April 2017 Contents Author’s “Read Me” Hunston Convent: Building, community and school Hunston Convent (or Chichester Carmel), in a nutshell The Hunston Convent: architecture and function The Hunston Convent’s layout and the Free School Hunston Convent and other monastery building types Hunston Convent and monastic purposes Hunston Convent: From monastery to school curriculum Hunston Convent and conservation (built environment) Hunston Convent and the history curriculum Hunston Convent and the sociology curriculum Hunston Convent and the politics curriculum Hunston Convent and business studies Hunston Convent: Monasticism and a wider pastoral context Carmelites and Englishwomen and feminism Carmelites and others, and the mendicant, spiritual tradition Christian monastics and multiculturalism Christian monastics and spirituality Christian monastics and attitudes toward the world Christian monastics and usefulness Christian monastics and well-being Christian monastics and green thinking Christian monastics and hospitality Christian monastics and learning Hunston Convent and monastic suppression Hunston Convent, the Gothic, and the aesthetics of dereliction Internet research leads Document begins Author’s “Read Me” This is the latest version of a work in progress. This draft has been peer-reviewed by two senior Carmelite nuns. Please challenge the document as to fact or opinion. It’s longish: the contents table may save frustration. -

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mullen High to Take Day Pupils Denvircatholic Work Halted on Ten Projects

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mother Augustina Returns to Germany Next Month But Her Heart Will Remain in Colorado A grgantic Benedioine convent, a St. Walburga’s of ser of Eichstaett. That day is the Feast of the Holy Name In 1949 when Mother Augustina visited the German as Abbess will be as custodian and distributor of the famed the West, is the W jo c h o p e envisioned by Mother M. of Mary, a name that Mother Augustina bears as'' a nun. mother-house and conferred with the late Lady Abbess Ben- St. Walburga oil. This oil exudes from the bones of the Augustina Weihermuellcrp^perior of St. Walbutga’s con The ceremony will be held in St. Walburga’s parish church edicta, whom she has succeeejed, among the subjects con saint, who founded the Benedictine community and lived vent in South Boulder, as she prepares to return to Ger and the cloistered nuns of the community will witness it sidered wJs the possibility of transferring the heart of the 710-780. Many remarkable cures have been attributed many to assume her position as, Lady Abbess at the mother- ffom their private choir. order to America if Russia should:overrun Europe! to its use while seeking the intercession o f St. Walburga. house of her community in Eidistaett, Bavaria. That day, just two months hence, will mark the first At the great St. Walburga’s mother-house in Eich 'Those who have heard Mother Augustina in one of her Mother Augustina’s departure for Europe is scheduled time that an American citizen ,has returned to Europe to staett, she will be superior of 130 sisters. -

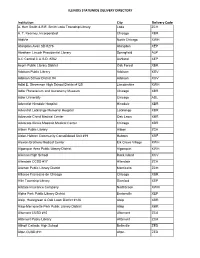

Illinois Statewide Delivery Directory

ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY Institution City Delivery Code A. Herr Smith & E.E. Smith Loda Township Library Loda ZCH A. T. Kearney, Incorporated Chicago XBR AbbVie North Chicago XWH Abingdon-Avon SD #276 Abingdon XEP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Springfield ALP A-C Central C.U.S.D. #262 Ashland XEP Acorn Public Library District Oak Forest XBR Addison Public Library Addison XGV Addison School District #4 Addison XGV Adlai E. Stevenson High School District #125 Lincolnshire XWH Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum Chicago XBR Adler University Chicago ADL Adventist Hinsdale Hospital Hinsdale XBR Adventist LaGrange Memorial Hospital LaGrange XBR Advocate Christ Medical Center Oak Lawn XBR Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago XBR Albion Public Library Albion ZCA Alden-Hebron Community Consolidated Unit #19 Hebron XRF Alexian Brothers Medical Center Elk Grove Village XWH Algonquin Area Public Library District Algonquin XWH Alleman High School Rock Island XCV Allendale CCSD #17 Allendale ZCA Allerton Public Library District Monticello ZCH Alliance Francaise de Chicago Chicago XBR Allin Township Library Stanford XEP Allstate Insurance Company Northbrook XWH Alpha Park Public Library District Bartonville XEP Alsip, Hazelgreen & Oak Lawn District #126 Alsip XBR Alsip-Merrionette Park Public Library District Alsip XBR Altamont CUSD #10 Altamont ZCA Altamont Public Library Altamont ZCA Althoff Catholic High School Belleville ZED Alton CUSD #11 Alton ZED ILLINOIS STATEWIDE DELIVERY DIRECTORY AlWood CUSD #225 Woodhull -

Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Media Center Bujanovac SPA Phone: +38164 5558581; +38161 6154768; [email protected]

Telenet Hotels Network | Serbia Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Media Center Bujanovac SPA Phone: +38164 5558581; +38161 6154768; www.booking-hotels.biz [email protected] Hotel Prohor Pcinjski, Spa Bujanovac Hotel has 100 beds, 40 rooms in 2 single rooms, 22 double rooms, 5 rooms with three beds, and 11 apartments. Hotel has restaurant, aperitif bar, and parking. Restaurant has 160 seats. All rooms have telephone, TV, and SATV. Bujanovac SPA Serbia Bujanovacka spa is located at the southernmost part of Serbia, 2,5 km away from Bijanovac and 360 km away from Belgrade, at 400 m above sea level. Natural curative factors are thermal mineral waters, curative mud [peloid] and carbon dioxide. Medical page 1 / 9 Indications: rheumatic diseases, recuperation states after injuries and surgery, some cardiovascular diseases, peripheral blood vessel diseases. Medical treatment is provided in the Institute for specialized rehabilitation "Vrelo" in Bujanovacka Spa. The "Vrelo" institute has a diagnostic-therapeutic ward and a hospital ward within its premises. The diagnostic-therapeutic ward is equipped with the most modern means for diagnostics and treatment. Exceptional treatment results are achieved by combining the most modern medical methods with the curative effect of the natural factors - thermal mineral waters, curative mud and natural gas. In the vicinity of Bujanovacka Spa there is Prohorovo, an area with exceptional natural characteristics. In its centre there is the St. Prohor Pcinjski monastery, dating from the 11th century, with a housing complex that was restored for the purpose of tourist accommodation. The Prohorovo area encompasses the valley of the river Pcinja and Mounts Kozjak and Rujan, and is an area exceptionally pleasant for excursions and hunting. -

Подкласс Exogenia Collin, 1912

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com Contribution to the knowledge of distribution of Colubrid snakes in Serbia LJILJANA TOMOVIĆ1,2,4*, ALEKSANDAR UROŠEVIĆ2,4, RASTKO AJTIĆ3,4, IMRE KRIZMANIĆ1, ALEKSANDAR SIMOVIĆ4, NENAD LABUS5, DANKO JOVIĆ6, MILIVOJ KRSTIĆ4, SONJA ĐORĐEVIĆ1,4, MARKO ANĐELKOVIĆ2,4, ANA GOLUBOVIĆ1,4 & GEORG DŽUKIĆ2 1 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Biology, Studentski trg 16, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 2 University of Belgrade, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stanković”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 3 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Dr Ivana Ribara 91, 11070 Belgrade, Serbia 4 Serbian Herpetological Society “Milutin Radovanović”, Bulevar despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia 5 University of Priština, Faculty of Science and Mathematics, Biology Department, Lole Ribara 29, 38220 Kosovska Mitrovica, Serbia 6 Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia, Vožda Karađorđa 14, 18000 Niš, Serbia *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Received 28 March 2015 │ Accepted 31 March 2015 │ Published online 6 April 2015. Abstract Detailed distribution pattern of colubrid snakes in Serbia is still inadequately described, despite the long historical study. In this paper, we provide accurate distribution of seven species, with previously published and newly accumulated faunistic records compiled. Comparative analysis of faunas among all Balkan countries showed that Serbian colubrid fauna is among the most distinct (together with faunas of Slovenia and Romania), due to small number of species. Zoogeographic analysis showed high chorotype diversity of Serbian colubrids: seven species belong to six chorotypes. South-eastern Serbia (Pčinja River valley) is characterized by the presence of all colubrid species inhabiting our country, and deserves the highest conservation status at the national level. -

Sister Maura Therese Power, RSM Sisters of Mercy of Auburn, California

SACRAMENTO DIOCESAN ARCHIVE Vol 7 Father John E Boll No 2 Sister Maura Therese Power, RSM Sisters of Mercy of Auburn, California Maura Therese Power was born on October 8, 1937, in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland. She and her twin brother John Joseph were born to Denis Power and Philomena Freeley. Two days later, Maura and John were baptized at the Cathedral in Killarney. In addition to her twin brother, she has an older brother Gerard and a younger sister Noreen. The last born child was Catherine “Riona” who died at the age of seven, having lived with Down syndrome. BEGINNING THE EDUCATION PROCESS All the children of the Power family began their education at age four at the Mercy Convent School in Killarney. After each child received First Holy Communion, the boys went to the Presentation Brothers School and the girls continued with the Mercy Sisters. FAMILY FORCED TO MOVE TO DUBLIN Maura’s father Denis worked in Hilliard’s Department Store. When labor disputes arose in the mid-1940s, Denis lost his job at the store and was forced to go to Dublin to look for another position. He secured a new job in Dublin and the family moved to Dublin in 1949. Since this was right after the end of World War II, life was difficult for everyone in Europe as well as the Power family in Ireland. After arriving in Dublin, the family settled in Clontarf along the coast in a new house that Maura’s father was able to purchase. She began secondary school with the Irish Sisters of Charity on King’s Inn Street. -

Celebrating 90 Years of Monastic Life. 1927-2017

LENSTAL ABBEY CHRONICLE Celebrating 90 years of GLENSTAL ABBEY monastic life. Murroe, Co Limerick www.glenstal.org 1927-2017 www.glenstal.com (061)621000 S T A Y I N TOUCH WITH G L E N S T A L ABBEY If you would like to receive emails from Glenstal about events and other goings on please join our email list on our website. You can decide what type of emails you will receive and can change this at any stage. Your data will not be used for any other purpose. 1 | P a g e CELEBRATING 90 YEARS OF MONASTIC LIFE 1 9 2 7 - 2 0 1 7 Welcome Contents On the 90th anniversary of our foundation it is our pleasure to share Where in the World…… page 3 with you, friends, benefactors, Oblates at Glenstal….. page 6 parents, students, colleagues and School Choir…………… page 8 visitors, something of the variety and richness of life here in Glenstal Out of Africa…………… page 10 Abbey. In the pages of this My Year in Glenstal Chronicle we hope to bring alive and UL…………………… page 13 the place which we are privileged Glenstal Abbey Farm… page 14 to call home. Thinking of Monastic Life……………………….. page 15 We have come a very long Life as a Novice……….. page 15 way from those early days when the first Belgian monks arrived here Malartú Daltaí le back in 1927. What has been Scoileanna thar Lear…. page 18 achieved is thanks in no small Guest House……………. page 19 measure to the kindness and Retreat Days……………. -

Missouri's Pioneer Nun “Canonization! That's Wonderful,” Said Virginia Robyn of St. Louis County, Who Is 91

06H Missouri's Pioneer Nun 1 [3261 words] Missouri’s Pioneer Nun Patricia J. Rice First published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Magazine, August 23, 1987 Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, copyright 1987 “Canonization! That’s wonderful,” said Virginia Robyn of St. Louis County, who is 91. Her grandmother, Mary Knott Dyer, who was a student of Mother Duchesne, told her the girls vied to thread their beloved teacher’s sewing needle when her sight was failing. Mother Duchesne, who was born in France, stepped off the steamboat, Franklin, at St. Louis in 1818. All but one of her remaining thirty-eight years were spent in St. Charles, Florissant, and St. Louis, teaching girls. In St. Charles she founded the first free school west of the Mississippi, and in Florissant, she began the first school for native Americans west of the river. She and the four nuns that came with her were the first nuns to settle here. She was a voluminous correspondent; her 528 surviving letters and a convent journal she kept are fascinating chronicles of a booming St. Louis. Mother Duchesne might well be called a patron of flexible, active older people. She arrived in America on the eve of her forty-ninth birthday; when she finally fulfilled her lifelong dream of living among the Indians in Kansas, she was seventy-two and infirm. She lived in a world that was changing dramatically. She could become the patron of feminists. Mother Duchesne pushed the limits of what was allowed to a woman in her times. -

The Seals of Reading Abbey

The Seals of Reading Abbey Brian Kemp, University of Reading The splendid fourteenth-century common seal of Reading Abbey is justifiably well known, but it is only one among several seals of various kinds to have survived from the abbey. The others include the first common seal, dating from the twelfth century, a series of personal seals of individual abbots beginning in the later twelfth century. at least two counterseals from the thirteenth century and a small seal used by the abbot and convent when acting as clerical tax collectors in the fourteenth century. All these seals had, of course, a primarily legal function. They were used to authenticate and enhance the legal force of the documents to which they were affixed. Equally, however, they can be regarded as miniature works of art which not only exemplify the stylistic fashions of their times, but also throw light on other matters not directly connected with their legal function. In particular, the evolving iconography of the Reading seals between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries provides an interesting commentary on the growth of the cult of St James the Great in the abbey, based on its principal relic, a hand of the apostle. Though not present on the earliest seals, depictions of the hand and other references to St James begin to occur in the first half of the thirteenth century and become quite prominent by the end of it. This paper is concerned with examining these developments, but it must be admitted at the outset that there are some important gaps in the account, since no Reading seals have been found for certain key periods. -

Transforming Our World in Harmony with Nature

TRANSFORMING OUR WORLD IN HARMONY WITH NATURE Integrating Nature while Implementing the UN's 2019 Sustainable Development Goals TRANSFORMING OUR WORLD IN HARMONY WITH NATURE Integrating Nature while Implementing the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals CHIEF AUTHORS OF THE ENCLOSED REPORTS Marilyn Fowler, MA, PhD., Department of Consciousness and Sustainable Development John F. Kennedy University Joan Kehoe, MSC Maia Kincaid, PhD. Founder of the Sedona International School for Nature and Animal Communication Consultant and International Lecturer Jill Lauri, MBA, MSW Lee Samatowic, ND Lisinka Ulatowska, MA, PhD. UN Representative, AWN, AWC, IPS Coordinator, Commons Cluster of the UN NGO Major Group Rob Wheeler Main UN Representative, Global Ecovillage Network Produced by the Commons Cluster of the UN NGO Major Group for the Partnership on the Right of Nature. Integrating Nature into the Implementation of the SDGs. LAYOUT AND FORMATTING Tonny van Knotsenburg COVER AND CHAPTER DESIGN Devin Lafferty, CreativSense CONTACT Lisinka Ulatowska, Coordinator [email protected] CONTENTS Introduction 5 Executive Summary: Transforming our World in Harmony with Nature, Integrating Nature while Implementing the SDGs 6 Part I: Integrating Nature with the UN’s 2019 Sustainable Development Goals 37 SDG 4: Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All...............................................................38 Introduction Targets SDG 8: Promote Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic -

A Nigerian Experiment

6 A MONASTIC SECOND SPRING The Re-establishment of Benedictine life in Britain HE DISSOLUTION of the English Monasteries and other great Religious Houses by King Henry VIII virtually destroyed monastic life in Britain and Ireland in the five short years T between 1535 and 1540. So dominant had been the monks' con- tribution to the English 'thing' in the sphere of religious practice, so forceful its social, economic and political impact, that the spiritual and topographical shape of the country was entirely changed. Only gaunt and empty buildings remained as witnesses of a noble past that reached back for close on a thousand years. The visible absence of monasteries was to haunt the countryside and townships of these islands for nearly three centuries. If men and women from Great Britain and Ireland, who had remained loyal to the ancient faith of Columba and Aidan, Gregory and Augustine, felt the call to follow Christ along the monastic path, they had to leave home for the continent of Europe. At the outset, its men joined monasteries in Italy and Spain. But later, they became numerous enough to band together. With the approval of Rome, they reshaped an English Congregation of Monasteries in the Netherlands, France and Germany. There they waited patiently, until God's time should come for them to return and to re-found their monasteries in the homeland. The english monks settled at Douai (St Gregory's), at Dieuleward, Lorraine (St Laurence's) and at Paris (St Edmund's); the Scots established monasteries at Ratisbon and Wurzburg. The nuns settled earlier at Brussels, Cambrai and Ghent, at Dunkirk and Paris.