A Nigerian Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tavistock Abbey

TAVISTOCK ABBEY Tavistock Abbey, also known as the Abbey of Saint Mary and Saint Rumon was originally constructed of timber in 974AD but 16 years later the Vikings looted the abbey then burned it to the ground, the later abbey which is depicted here, was then re-built in stone. On the left is a 19th century engraving of the Court Gate as seen at the top of the sketch above and which of course can still be seen today near Tavistock’s museum. In those early days Tavistock would have been just a small hamlet so the abbey situated beside the River Tavy is sure to have dominated the landscape with a few scattered farmsteads and open grassland all around, West Down, Whitchurch Down and even Roborough Down would have had no roads, railways or canals dividing the land, just rough packhorse routes. There would however have been rivers meandering through the countryside of West Devon such as the Tavy and the Walkham but the land belonging to Tavistock’s abbots stretched as far as the River Tamar; packhorse routes would then have carried the black-robed monks across the border into Cornwall. So for centuries, religious life went on in the abbey until the 16th century when Henry VIII decided he wanted a divorce which was against the teachings of the Catholic Church. We all know what happened next of course, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when along with all the other abbeys throughout the land, Tavistock Abbey was raised to the ground. Just a few ruined bits still remain into the 21st century. -

Hunston Convent and Its Reuse As Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North R North- at - Fastmail.Net 25 April 2017

Hunston Convent and its reuse as Chichester Free School, 2016 - Notes by Richard D North r_north- at - fastmail.net 25 April 2017 Contents Author’s “Read Me” Hunston Convent: Building, community and school Hunston Convent (or Chichester Carmel), in a nutshell The Hunston Convent: architecture and function The Hunston Convent’s layout and the Free School Hunston Convent and other monastery building types Hunston Convent and monastic purposes Hunston Convent: From monastery to school curriculum Hunston Convent and conservation (built environment) Hunston Convent and the history curriculum Hunston Convent and the sociology curriculum Hunston Convent and the politics curriculum Hunston Convent and business studies Hunston Convent: Monasticism and a wider pastoral context Carmelites and Englishwomen and feminism Carmelites and others, and the mendicant, spiritual tradition Christian monastics and multiculturalism Christian monastics and spirituality Christian monastics and attitudes toward the world Christian monastics and usefulness Christian monastics and well-being Christian monastics and green thinking Christian monastics and hospitality Christian monastics and learning Hunston Convent and monastic suppression Hunston Convent, the Gothic, and the aesthetics of dereliction Internet research leads Document begins Author’s “Read Me” This is the latest version of a work in progress. This draft has been peer-reviewed by two senior Carmelite nuns. Please challenge the document as to fact or opinion. It’s longish: the contents table may save frustration. -

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mullen High to Take Day Pupils Denvircatholic Work Halted on Ten Projects

Abbess-Elect Envisions Great U. S. Benedictine Convent Mother Augustina Returns to Germany Next Month But Her Heart Will Remain in Colorado A grgantic Benedioine convent, a St. Walburga’s of ser of Eichstaett. That day is the Feast of the Holy Name In 1949 when Mother Augustina visited the German as Abbess will be as custodian and distributor of the famed the West, is the W jo c h o p e envisioned by Mother M. of Mary, a name that Mother Augustina bears as'' a nun. mother-house and conferred with the late Lady Abbess Ben- St. Walburga oil. This oil exudes from the bones of the Augustina Weihermuellcrp^perior of St. Walbutga’s con The ceremony will be held in St. Walburga’s parish church edicta, whom she has succeeejed, among the subjects con saint, who founded the Benedictine community and lived vent in South Boulder, as she prepares to return to Ger and the cloistered nuns of the community will witness it sidered wJs the possibility of transferring the heart of the 710-780. Many remarkable cures have been attributed many to assume her position as, Lady Abbess at the mother- ffom their private choir. order to America if Russia should:overrun Europe! to its use while seeking the intercession o f St. Walburga. house of her community in Eidistaett, Bavaria. That day, just two months hence, will mark the first At the great St. Walburga’s mother-house in Eich 'Those who have heard Mother Augustina in one of her Mother Augustina’s departure for Europe is scheduled time that an American citizen ,has returned to Europe to staett, she will be superior of 130 sisters. -

Christian Monastic Communities Living in Harmony with the Environment: an Overview of Positive Trends and Best Practices 1

Christian monastic communities living in harmony with the environment: an overview of positive trends and best practices 1 Abstract This paper explores the relationship between Christian monastic communities and nature and the natural environment, a new field for this journal. After reviewing their historical origins and evolution, and discussing their key doctrinal principles regarding the environment, the paper provides an overview of the best practices developed by these communities of various sizes that live in natural surroundings, and reviews promising new trends. These monastic communities are the oldest self-organised communities in the Old World with a continuous history of land and environmental management, and have generally had a positive impact on nature and landscape conservation. Their experience in adapting to and overcoming environmental and economic crises is highly relevant in modern-day society as a whole and for environmental managers and policy makers in particular. This paper also argues that the efforts made by a number of monastic communities, based on the principles of their spiritual traditions, to become more environmentally coherent should be encouraged and publicized to stimulate more monastic communities to follow their example and thus to recapture the environmental and spiritual coherence of their ancestors. The paper concludes that the best practices in nature conservation developed by Christian 1 This paper is a substantial development, both in content and scope, of a previous paper written by one of us (JM) for the Proceedings of the Third workshop of The Delos Initiative, which took place in Lapland, Finland, in 2010. A certain number of the experiences discussed here comes from case studies prepared during the last nine years in the context of The Delos Initiative, jointly co-ordinated by two of us (TP, JM), within the IUCN World Commission of Protected Areas. -

NEWSLETTER September 2019

President: Secretary: Treasurer: David Illingworth Nigel Webb Malcolm Thorning 01305 848685 01929 553375 01202 659053 NEWSLETTER September 2019 FROM THE HON. SECRETARY Since the last Newsletter we have held some memorable meetings of which the visit, although it was a long and tiring day, to Buckfast Abbey must rank among the best we have had. Our visit took place on Thursday 16th May 2019 when some sixteen members assembled in the afternoon sunshine outside the Abbey to receive a very warm welcome from David Davies, the Abbey Organist. He gave us an introduction to the acquisition and building of the organ before we entered the Abbey. The new organ in the Abbey was built by the Italian firm of Ruffatti in 2017 and opened in April 2018. It has an elaborate specification of some 81 stops spread over 4 manuals and pedals. It is, in effect, two organs with a large west-end division and a second extensive division in the Choir. There is a full account of this organ in the Organist’s Review for March 2018 and on the Abbey website. After the demonstration we were invited to play. Our numbers were such that it was possible for everyone to take the opportunity. David was on hand to assist with registration on this complex instrument as the console resembled the flight deck of an airliner. Members had been asked to prepare their pieces before-hand and this worked well with David commenting on the excellent choice of pieces members had chosen to suit the organ. We are most grateful to David Davies for making us so welcome and help throughout the afternoon. -

The Network RSCM Events in Your Local Area June – October 2016

the network RSCM events in your local area June – October 2016 The Network June 2016.indd 1 16/05/2016 11:17:47 Welcome THE ROYAL SCHOOL OF You can travel the length and CHURCH MUSIC breadth of the British Isles this Registered Charity No. 312828 Company Registration No. summer, participate in and 00250031 learn about church music in 19 The Close, Salisbury SP1 2EB so many forms with the RSCM. T 01722 424848 I don’t think I’ve ever seen quite F 01722 424849 E [email protected] so varied and action-packed an W www.rscm.com edition of The Network. I am Front cover photograph: most grateful to the volunteers on the RSCM’s local Area RSCM Ireland award winners committees, and I hope you will feel able to take up this recording for an RTÉ broadcast, oering. November 2015 How to condense it? Awards, BBC broadcast, The Network editor: Contemporary worship music, Diocesan music day, Cathy Markall Evensongs, Food-based events, Gospel singing, Harvest Printed in Wales by Stephens & George Ltd anthems, Instrumental music, John Rutter, Knighton pilgrimage, Lift up your Voice, Music Sunday, National Please note that the deadline for submissions to the next courses, explore the Organ, converting Pianists, edition of The Network is celebrating the Queen’s birthday, Resources for small and 1 July 2016. rural churches, Singing breaks, Training organists, Using the voice well, Vespers, Workshops, events for Young ABOUT THE RSCM people. Excellence and zeal, I hope. The RSCM is a charity Don’t forget that there is also the triennial committed particularly to International Summer School in Liverpool in August promoting the study, practice and improvement of music at which you can experience many of these things in in Christian worship. -

Stage 1-Route-Guide-V3.Cdr

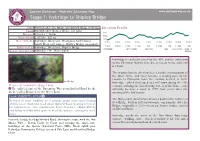

O MO R T W R A A Y D w w k u w . o .d c ar y. tmoorwa Start SX 6366 5627 Ivy Bridge on Harford Road, Ivybridge Elevation Profile Finish SX 6808 6289 Shipley Bridge car park 300m Distance 10 miles / 16 km 200m 2,037 ft / 621 m Total ascent 100m Refreshments Ivybridge, Bittaford, Wrangaton Golf Course, 0.0km 2.0km 4.0km 6.0km 8.0km 10.0km 12.0km 14.0km 16.0km South Brent (off route), Shipley Bridge (seasonal) 0.0mi 1.25mi 2.5mi 3.75mi 5mi 6.25mi 7.5mi 8.75mi 10mi Public toilets Ivybridge, Bittaford, Shipley Bridge IVYBRIDGE BITTAFORD CHESTON AISH BALL GATE SHIPLEY Tourist information Ivybridge (The Watermark) BRIDGE Ivybridge is easily accessed via the A38, and the only town on the Dartmoor Way to have direct access to the main rail network. The original hamlet developed at a handy crossing point of the River Erme, and later became a staging post on the London to Plymouth road; the railway arrived in 1848. Ivy Bridge Ivybridge - which developed as a mill town during the 19th Please refer also to the Stage 1 map. century, utilising the fast-flowing waters of the Erme - only S The official start of the Dartmoor Way is on Harford Road by the officially became a town in 1977, four years after the medieval Ivy Bridge over the River Erme. opening of the A38 bypass. POOR VISIBILITY OPTION a The Watermark (local information) is down in the town near In times of poor visibility or if anxious about your route-finding New Bridge, built in 1823 just downstream from the older Ivy abilities over moorland head down Harford Road, bearing left near Bridge, originally a 13th-century packhorse bridge, passed the bottom to meet the roundabout. -

Sister Maura Therese Power, RSM Sisters of Mercy of Auburn, California

SACRAMENTO DIOCESAN ARCHIVE Vol 7 Father John E Boll No 2 Sister Maura Therese Power, RSM Sisters of Mercy of Auburn, California Maura Therese Power was born on October 8, 1937, in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland. She and her twin brother John Joseph were born to Denis Power and Philomena Freeley. Two days later, Maura and John were baptized at the Cathedral in Killarney. In addition to her twin brother, she has an older brother Gerard and a younger sister Noreen. The last born child was Catherine “Riona” who died at the age of seven, having lived with Down syndrome. BEGINNING THE EDUCATION PROCESS All the children of the Power family began their education at age four at the Mercy Convent School in Killarney. After each child received First Holy Communion, the boys went to the Presentation Brothers School and the girls continued with the Mercy Sisters. FAMILY FORCED TO MOVE TO DUBLIN Maura’s father Denis worked in Hilliard’s Department Store. When labor disputes arose in the mid-1940s, Denis lost his job at the store and was forced to go to Dublin to look for another position. He secured a new job in Dublin and the family moved to Dublin in 1949. Since this was right after the end of World War II, life was difficult for everyone in Europe as well as the Power family in Ireland. After arriving in Dublin, the family settled in Clontarf along the coast in a new house that Maura’s father was able to purchase. She began secondary school with the Irish Sisters of Charity on King’s Inn Street. -

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: a Book and a Film

Advent 2015 Two Recent Publications: A Book and a Film Monks have long been known for their diverse tal- on the afternoon of Sunday, September 13, attended ents and interests: teachers, farmers, writers, artists. by a number of Fr Stephen’s former students and Among the last-named was Fr Stephen Reid of our other friends of the abbey. It is available in our gift community, who at the time of his death in 1989 had shop for $20, and can be ordered by mail for an produced a remarkable number of sculptures and additional four dollars to cover shipping costs. paintings. In the past few years, an art critic named We think our readers would also like to know Bruce Nixon has been working on a publication that of a documentary about Benedictine life that has offers a thoughtful, carefully researched interpretive been produced for the Catholic French television text that considers Fr Stephen’s art in the context channel KTO, founded in 1999 by the late cardinal- of his life as a monk. Titled A Communion of Saints, archbishop of Paris, Jean-Marie Lustiger. Titled Le this forty-page illus- Temps et la règle bénédictine, this 52-minute film was trated catalog includes first telecast in December, 2014. The director, Patrice photographs made in Cros, has twice visited St Anselm’s and hopes accordance with the to produce English-language documentaries on archival standards of this and similar Benedictine topics, such as work, museum documenta- community, authority, and poverty. If any of our tion and so serves to readers have suggestions of sponsors who could preserve the legacy finance such a project, please let Abbot James know. -

Missouri's Pioneer Nun “Canonization! That's Wonderful,” Said Virginia Robyn of St. Louis County, Who Is 91

06H Missouri's Pioneer Nun 1 [3261 words] Missouri’s Pioneer Nun Patricia J. Rice First published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Magazine, August 23, 1987 Reprinted with permission of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, copyright 1987 “Canonization! That’s wonderful,” said Virginia Robyn of St. Louis County, who is 91. Her grandmother, Mary Knott Dyer, who was a student of Mother Duchesne, told her the girls vied to thread their beloved teacher’s sewing needle when her sight was failing. Mother Duchesne, who was born in France, stepped off the steamboat, Franklin, at St. Louis in 1818. All but one of her remaining thirty-eight years were spent in St. Charles, Florissant, and St. Louis, teaching girls. In St. Charles she founded the first free school west of the Mississippi, and in Florissant, she began the first school for native Americans west of the river. She and the four nuns that came with her were the first nuns to settle here. She was a voluminous correspondent; her 528 surviving letters and a convent journal she kept are fascinating chronicles of a booming St. Louis. Mother Duchesne might well be called a patron of flexible, active older people. She arrived in America on the eve of her forty-ninth birthday; when she finally fulfilled her lifelong dream of living among the Indians in Kansas, she was seventy-two and infirm. She lived in a world that was changing dramatically. She could become the patron of feminists. Mother Duchesne pushed the limits of what was allowed to a woman in her times. -

The Seals of Reading Abbey

The Seals of Reading Abbey Brian Kemp, University of Reading The splendid fourteenth-century common seal of Reading Abbey is justifiably well known, but it is only one among several seals of various kinds to have survived from the abbey. The others include the first common seal, dating from the twelfth century, a series of personal seals of individual abbots beginning in the later twelfth century. at least two counterseals from the thirteenth century and a small seal used by the abbot and convent when acting as clerical tax collectors in the fourteenth century. All these seals had, of course, a primarily legal function. They were used to authenticate and enhance the legal force of the documents to which they were affixed. Equally, however, they can be regarded as miniature works of art which not only exemplify the stylistic fashions of their times, but also throw light on other matters not directly connected with their legal function. In particular, the evolving iconography of the Reading seals between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries provides an interesting commentary on the growth of the cult of St James the Great in the abbey, based on its principal relic, a hand of the apostle. Though not present on the earliest seals, depictions of the hand and other references to St James begin to occur in the first half of the thirteenth century and become quite prominent by the end of it. This paper is concerned with examining these developments, but it must be admitted at the outset that there are some important gaps in the account, since no Reading seals have been found for certain key periods. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'.