(Gcc): a Kuwaiti Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0.30560 0.30570 Daily Treasury Market Commentary KUWAITI DINAR

KUWAITI DINAR 0.30560 0.30570 Daily Treasury Market Commentary October 28, 2020 Foreign Exchange Developments: Economic Updates: The euro fell against the dollar on Wednesday following a New orders for key US-made capital goods increased Currency Price MTD % 3M% YTD% media report that France's government was leaning to six-year high in September, wrapping up a quarter EUR/USD 1.1779 0.51 0.55 5.07 toward reinstating a national lockdown to curb a of potentially record growth in business spending and GBP/USD 1.3043 0.98 0.87 -1.64 resurgence in coronavirus cases. the economy. AUD/USD 0.7145 -0.24 -0.18 1.75 The dollar, however, gave up early gains against other Britain must spell out how far it wants to diverge from USD/CHF 0.909 -1.28 -0.98 -6.09 major currencies as sentiment turned bearish due to European Union rules if it wants access to the bloc's USD/JPY 104.26 -1.16 -0.81 -4.25 uncertainty about the outcome of the U.S. presidential financial market from January, a top European USD/CAD 1.3191 -0.97 -1.39 1.57 election next week. The euro fell 0.14% to $1.1780 in Asia Commission official said on Tuesday. on Wednesday, down for a third consecutive session. Sterling held steady at $1.3035, supported by hopes for a Local & GCC news: last-minute trade deal between Britain and the European Kuwait's central bank announced on Tuesday it was Index Price Change MTD% YTD% Union. -

Countries Codes and Currencies 2020.Xlsx

World Bank Country Code Country Name WHO Region Currency Name Currency Code Income Group (2018) AFG Afghanistan EMR Low Afghanistan Afghani AFN ALB Albania EUR Upper‐middle Albanian Lek ALL DZA Algeria AFR Upper‐middle Algerian Dinar DZD AND Andorra EUR High Euro EUR AGO Angola AFR Lower‐middle Angolan Kwanza AON ATG Antigua and Barbuda AMR High Eastern Caribbean Dollar XCD ARG Argentina AMR Upper‐middle Argentine Peso ARS ARM Armenia EUR Upper‐middle Dram AMD AUS Australia WPR High Australian Dollar AUD AUT Austria EUR High Euro EUR AZE Azerbaijan EUR Upper‐middle Manat AZN BHS Bahamas AMR High Bahamian Dollar BSD BHR Bahrain EMR High Baharaini Dinar BHD BGD Bangladesh SEAR Lower‐middle Taka BDT BRB Barbados AMR High Barbados Dollar BBD BLR Belarus EUR Upper‐middle Belarusian Ruble BYN BEL Belgium EUR High Euro EUR BLZ Belize AMR Upper‐middle Belize Dollar BZD BEN Benin AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BTN Bhutan SEAR Lower‐middle Ngultrum BTN BOL Bolivia Plurinational States of AMR Lower‐middle Boliviano BOB BIH Bosnia and Herzegovina EUR Upper‐middle Convertible Mark BAM BWA Botswana AFR Upper‐middle Botswana Pula BWP BRA Brazil AMR Upper‐middle Brazilian Real BRL BRN Brunei Darussalam WPR High Brunei Dollar BND BGR Bulgaria EUR Upper‐middle Bulgarian Lev BGL BFA Burkina Faso AFR Low CFA Franc XOF BDI Burundi AFR Low Burundi Franc BIF CPV Cabo Verde Republic of AFR Lower‐middle Cape Verde Escudo CVE KHM Cambodia WPR Lower‐middle Riel KHR CMR Cameroon AFR Lower‐middle CFA Franc XAF CAN Canada AMR High Canadian Dollar CAD CAF Central African Republic -

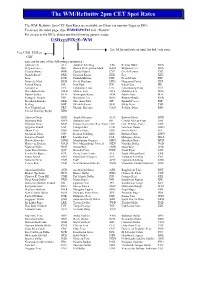

WM/Refinitiv 2Pm CET Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates The WM/ Refinitiv 2pm CET Spot Rates are available on Eikon via monitor Pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRESPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes : USDxxxFIXzE=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR or GBP xxx can be any of the following currencies : Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy Ariary -

Security Council GENERAL

UNITED NATIONS S Distr. Security Council GENERAL S/AC.26/1999/17 30 September 1999 Original: ENGLISH UNITED NATIONS COMPENSATION COMMISSION GOVERNING COUNCIL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS MADE BY THE PANEL OF COMMISSIONERS CONCERNING THE SECOND INSTALMENT OF “E4” CLAIMS GE.99-66179 S/AC.26/1999/17 Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction .................... 1 - 3 4 I. OVERVIEW OF THE SECOND INSTALMENT CLAIMS .... 4 - 7 4 II. THE PROCEEDINGS ................ 8 - 27 5 III. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ................ 28 8 IV. VERIFICATION AND VALUATION OF CLAIMS ...... 29 8 V. THE CLAIMS ................... 30- 109 8 A. Contract .................. 31- 43 9 1. Compensability ............. 36 9 2. Verification and valuation method . 37 9 3. Evidence submitted .......... 38- 43 10 B. Real property ............... 44- 51 11 1. Compensability ............. 45- 46 11 2. Verification and valuation method . 47 11 3. Evidence submitted ........... 48- 51 11 C. Tangible property ............. 52- 65 12 1. Compensability ............. 53 12 2. Verification and valuation method . 54 12 3. Evidence submitted ........... 55- 65 12 (a) Tangible property ......... 55- 56 12 (b) Stock ............... 57- 59 13 (c) Cash ............... 60- 61 13 (d) Vehicles ............. 62- 65 14 D. Income-producing property ......... 66- 69 14 E. Payment or relief to others ........ 70- 78 15 1. Compensability ............. 71- 74 15 2. Verification and valuation method . 75 16 3. Evidence submitted ........... 76- 78 17 F. Loss of profits .............. 79- 85 17 1. Compensability ............. 80 17 2. Verification and valuation method . 81 17 3. Evidence submitted ........... 82- 85 18 G. Receivables ................ 86- 92 18 1. Compensability ............. 87- 88 18 2. Verification and valuation method . 89 19 3. Evidence submitted ........... 90- 92 19 H. -

The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-1968

The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-1968 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Orkaby, Asher Aviad. 2014. The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-1968. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269828 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-1968 A dissertation presented by Asher Aviad Orkaby to The Committee on Middle Eastern Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History and Middle Eastern Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2014 © 2014 Asher Aviad Orkaby All rights reserved. III Dissertation Advisor: Roger Owen Author: Asher Aviad Orkaby The International History of the Yemen Civil War, 1962-68 Abstract The deposition of Imam Muhammad al-Badr in September 1962 was the culmination of a Yemeni nationalist movement that began in the 1940s with numerous failed attempts to overthrow the traditional religious legal order. Prior to 1962, both the USSR and Egypt had been cultivating alliances with al-Badr in an effort to secure their strategic interests in South Arabia. In the days following the 1962 coup d'état, Abdullah Sallal and his cohort of Yemeni officers established a republic and concealed the fate of al- Badr who had survived an assault on his Sana’a palace and whose supporters had already begun organizing a tribal coalition against the republic. -

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M

North York Coin Club Founded 1960 MONTHLY MEETINGS 4TH Tuesday 7:30 P.M. AT Edithvale Community Centre, 131 Finch Ave. W., North York M2N 2H8 MAIL ADDRESS: NORTH YORK COIN CLUB, 5261 Naskapi Court, Mississauga, ON L5R 2P4 Web site: www.northyorkcoinclub.com Contact the Club : Executive Committee E-mail: [email protected] President ........................................Bill O’Brien Director ..........................................Roger Fox Auction Manager..........................Paul Johnson Phone: 416-897-6684 1st Vice President ..........................Henry Nienhuis Director ..........................................Paul Johnson Editor ..........................................Paul Petch 2nd Vice President.......................... Director ..........................................Andrew Silver Receptionist ................................Franco Farronato Member : Secretary ........................................Henry Nienhuis Junior Director ................................ Draw Prizes ................................Bill O’Brien Treasurer ........................................Ben Boelens Auctioneer ......................................Dick Dunn Social Convenor ..........................Bill O’Brien Ontario Numismatic Association Past President ................................Nick Cowan Royal Canadian Numismatic Assocation THE BULLETIN FOR MARCH 2017 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NEXT MEETING Good day to all fellow numismatists and Speaking about the R.C.N.A., it’s not too TUESDAY, MARCH 28 our members and friends who receive -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

Al Ain, United Arab Emirates Destination Guide

Al Ain, United Arab Emirates Destination Guide Overview of Al Ain The merging of ancient and modern Arabic culture is no more evident than in the fascinating city of Al Ain, about 100 miles (160km) east of Abu Dhabi (near the Omani border with Buraimi). Known as the 'Garden city of the Gulf' because of its tree-lined boulevards and green public spaces, this historic, scenic oasis is surrounded by red sand dunes and dominated by a vast mountain range in the eastern UAE. Founded around 3,000 BC, Al Ain was an important oasis along caravan routes between Oman and the UAE. The oasis itself consists of thousands of date palms, now located near the main souq downtown. It is fed by underground hot springs that bubble to the surface in the Green Mubazzarah recreation area. Al Ain's heritage is still evident in the bustling camel market, located near the Meyzad border crossing. Hundreds of camels are bought and sold each day, and traders are very friendly to tourists. The Al Ain Museum and Fort is another historical attraction worth visiting, with exhibits depicting daily life in ancient Arabia. Al Ain is a modern city, filled with luxury resort hotels and shiny shopping malls. An exciting theme park, the renowned Al Ain Zoo, and an Olympic-sized ice rink are just a few of the popular attractions for tourists to enjoy. Key Facts Language: Arabic is the official language of the Emirates, but English is widely spoken. Passport/Visa: All visitors to the United Arab Emirates must hold a passport that is valid for six months. -

ANNEX a to the 1998 FX and CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED and RESTATED AS of NOVEMBER 19, 2017 I

ANNEX A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions _________________________ Amended and Restated November 19, 2017 Amended March 16, 2020 INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. TRADE ASSOCIATION FOR THE EMERGING MARKETS Copyright © 2000-2020 by INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. EMTA, INC. ISDA and EMTA consent to the use and photocopying of this document for the preparation of agreements with respect to derivative transactions and for research and educational purposes. ISDA and EMTA do not, however, consent to the reproduction of this document for purposes of sale. For any inquiries with regard to this document, please contact: INTERNATIONAL SWAPS AND DERIVATIVES ASSOCIATION, INC. 10 East 53rd Street New York, NY 10022 www.isda.org EMTA, Inc. 405 Lexington Avenue, Suite 5304 New York, N.Y. 10174 www.emta.org TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 i ANNEX A CALCULATION OF RATES FOR CERTAIN SETTLEMENT RATE OPTIONS SECTION 4.3. Currencies 1 SECTION 4.4. Principal Financial Centers 6 SECTION 4.5. Settlement Rate Options 9 A. Emerging Currency Pair Single Rate Source Definitions 9 B. Non-Emerging Currency Pair Rate Source Definitions 21 C. General 22 SECTION 4.6. Certain Definitions Relating to Settlement Rate Options 23 SECTION 4.7. Corrections to Published and Displayed Rates 24 INTRODUCTION TO ANNEX A TO THE 1998 FX AND CURRENCY OPTION DEFINITIONS AMENDED AND RESTATED AS OF NOVEMBER 19, 2017 Annex A to the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions ("Annex A"), originally published in 1998, restated in 2000 and amended and restated as of the date hereof, is intended for use in conjunction with the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions, as amended and updated from time to time (the "FX Definitions") in confirmations of individual transactions governed by (i) the 1992 ISDA Master Agreement and the 2002 ISDA Master Agreement published by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. -

Multi-Currency Capability

■ www.unisonmarketplace.com Multi-Currency Capability Unison Marketplace now offers a new feature that will support multiple currencies. This feature will allow Buyers to solicit requirements on the Marketplace and receive bids from the Seller community in different currencies (i.e. EUR, MXN, THB, CNY, PLN, etc.). Based on feedback from our growing pool of customers in remote areas and across global agencies, we have implemented this feature to further adapt to unique purchasing needs. Benefits Bid in your local currency. Increased access Faster bidding. Bid and receive orders in your local to opportunities. Submit your bids without the need to convert currency when accepted by Buyers on the More opportunities may be available from to USD when the Buyer allows multiple Marketplace. global customers. currencies. Utilizing Multi-Currency Submitting a bid in an alternative currency: 1. When bidding on a buy, a list of buyer-selected currencies will be available to choose from on the ‘Terms’ page. Using the drop down menu, select the currency in which you wish to bid. 2. On the ‘Line Items’ page, enter your pricing in your selected currency. 1 3. Review the pricing on the ‘Review and Submit’ page before submitting your bid. Please note: the pricing will appear in your selected currency, however all bids will be converted to U.S. dollars for Buyer evaluation If you have questions about Multi-Currency capabilities, at the currency exchange rate indicated in the please contact [email protected]. bidding requirements. The Buyer will see both the U.S. dollar and selected currency when reviewing your bid. -

CCT Master Currency List-WU

Currency Bank Name Africa Code Kenyan Shilling KES Stanbic Bank, Nairobi Namibian Dollar NAD Standard Bank Namibia, Ltd, Windhoek South African Rand ZAR Standard Bank of South Africa, Johannesburg Currency Bank Name Asia Code Chinese Yuan CNY Citic Bank Hong Kong Dollar HKD Standard Chartered Bank, Hong Kong Indian Rupee INR ICICI Bank Japanese Yen JPY Standard Chartered Bank, Tokyo Singapore Dollar SGD The Bank of New York Mellon Thai Bhat THB HSBC Bank, Bangkok Currency Bank Name Australia / Oceania Code Australian Dollar AUD HSBC Bank, Sydney Fiji Dollar FJD Westpac Banking Corporation, Suva New Zealand Dollar NZD Westpac Banking Corporation, Wellington Samoan Tala WST Westpac Bank Samoa Limited, Apia Tahitian (Central Polynesian) Franc XPF Banque de Polynesie, Papeete Vanuatu Vatu VUV Westpac Banking Corporation, Port Vila Currency Bank Name Europe Code British Pound GBP HSBC Bank PLC, London Czech Republic Koruna CZK Ceskoslovenska Obchodni Banka Danish Krone DKK Danske Bank, Copenhagen Euro (Main)* EUR HSBC Bank PLC, London Hungarian Forint HUF HSBC Bank PLC, London Latvian Lats LVL HSBC Bank PLC, London Lithuanian Litas LTL HSBC Bank PLC, London Norwegian Krone NOK Den Norske Bank, Oslo Polish Zloty PLN ING Bank, Poland Swedish Krona SEK Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken (SEB), Stockholm Swiss Franc CHF Credit Suisse, Zurich Currency Bank Name Middle East Code Bahrain Dinar BHD HSBC Bank PLC, London Israeli Shekel ILS HSBC Bank PLC, London Jordanian Dinar JOD HSBC Bank PLC, London Kuwaiti Dinar KWD HSBC Bank PLC, London Omani Rial -

Manama, Bahrain Destination Guide

Manama, Bahrain Destination Guide Overview of Manama First mentioned in Islamic chronicles in the year 1345, historical Manama is now the capital and largest city of Bahrain at the north-eastern tip of the Persian Gulf island state. There is a strong colonial influence in the area, with Portuguese occupation in 1521 followed by Persian dominance in 1602. This lovely city is a great base from which to enjoy the stunning beaches, buildings and sites in the area. The economy of Manama was traditionally based on pearling, fishing, boat building, and trade, displays of which can now be seen in local museums. In 1932, the discovery of petroleum boosted the city's economy, which has recently diversified into tourism and retail. Open-minded and tolerant of other cultures, Manama is visited by a large number of foreigners each year. These visitors can enjoy a vast array of attractions, from souks(markets) and shopping malls to forts and pearl museums. There is also an active nightlife with many popular restaurants, bars, and clubs to choose from, making this a splendid vacation destination. Key Facts Language: Arabic is the official language in Bahrain, although English is widely understood and is used by most businesses. Passport/Visa: All persons who wish to enter Bahrain need a visa, except citizens of the Gulf Cooperation Council (Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates). Visas can be obtained on arrival or online at www.evisa.gov.bh. Not all nationalities qualify for visas on arrival. A passport valid for duration of stay is required, but it is recommended that passports be valid for at least six months beyond intended travel.