Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction in the Last Chapter, You Read About the Origins of Judaism

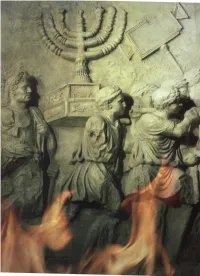

CHAPTER 4 Roman soldiers destroy theTemple of Jerusalem and carry off sacred treasures. The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you read about the origins of Judaism. In this chapter, you will discover how Judaism was preserved even after the Hebrews lost their homeland. As you have learned, the Hebrew kingdom split in two after the death of King Solomon. Weakened by this division, the Hebrews were less able to fight off invaders. The northern kingdom of Israel was the first to fall. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered Israel. The kingdom's leaders were carried off to Mesopotamia. In 597 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was invaded by another Meso- potamian power, Babylon. King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon laid siege to the city of Jerusalem. The Hebrews fought off the siege until their food ran out. With the people starving, the Babylonians broke through the walls and captured the city. In 586 B.C.E., Nebuchadrezzar burned down Solomon's great Temple of Jerusalem and all the houses in the city. Most of the people of Judah were taken as captives to Babylon. The captivity in Babylon was the begin- ning of the Jewish Diaspora. The word diaspora means "a scattering." Never again would most of the followers of Judaism be together in a single homeland. Yet the Jews, as they came to be known, were able to keep Judaism alive. In this chapter, you will first learn about four important Jewish beliefs. Then you will read about the Jews' struggle to preserve Judaism after they had been forced to settle in many lands. -

Name: Date: H.W.#: ___My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and The

Name: _____________________________ Date: __________________ H.W.#: ______ My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and the Jewish People” Section 1 – The Origins of Judaism ! Terms to understand when reading: 1. Jews – a group of people who share the same religious and cultural beliefs in God and worship following an ancient text known as the Torah. In ancient days, Jews were also known as the Hebrews and Israelites. Many Hebrews traveled from Canaan to Egypt to escape poverty, only to be enslaved by the Pharaohs. One of their leaders named Moses helped to free them from captivity in Egypt and led them back into Canaan (see the map) to an area that was to become known as the Jewish Promised Land. This land would later be called Judah, and much later known as Israel. In modern times, the ancient land of Canaan is now divided between Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Palestine. 2. monotheism - belief in one God. Jews, along with several other religions, believe that there is only one divine spirit who can be worshiped. In ancient times, the Hebrew God was sometimes referred to as Jehovah or Yahweh. Judaism, as a faith, is one of the world’s oldest religions and it said to date back at least 3000 years. (Some theologians place the religion’s date of origin closer to 4000 years.) 3. ethics - Simply put, ethics help to guide individuals from understanding right from wrong. The teaching of ethical principals is the foundation for most religions, including Judaism. In Judaism, as well as Christianity, the ethics of the religion and culture are clearly mapped out in the commandments. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

Scripturalization and the Aaronide Dynasties

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 6 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a6 Scripturalization and the Aaronide Dynasties JAMES W. WATTS Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203–1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs SCRIPTURALIZATION AND THE AARONIDE DYNASTIES JAMES W. WATTS SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY Evidence for the history of the Second Temple priesthood is very fragmentary and incomplete. To the best of our knowledge, how- ever, worship at the temple site in Jerusalem was controlled from ca. 535 to 172 B.C.E. by a single family, the descendants of Jeshua ben Jehozadak, the first post-exilic high priest (the family is often called the Oniads). After disruptions caused by civil wars and the Maccabean Revolt, they were replaced by another family, the Hasmoneans, who controlled the high priesthood from at least 152 until 37 B.C.E. Sources from the Second Temple period indicate that both families claimed descent from Israel’s first high priest, Aaron.1 1 For the Oniads’ genealogical claims, see 1 Chr 6:3–15; Ezra 2:36; 3:2. For the Hasmoneans’ claims, see 1 Macc 2:1; cf. 1 Chr 24:7. No ancient source challenges these claims, but many modern historians have been skeptical of them (e.g., J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel [trans. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

JUDAISM A Supplemental Resource for GRADE 12 World of Religions A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE JUDAISM A Supplemental Resource for GRADE 12 World of Religions A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE 2019 Manitoba Education Manitoba Education Cataloguing in Publication Data Judaism : Grade 12 world of religions : a Canadian perspective Includes bibliographical references. This resource is available in print and electronic formats. ISBN: 978-0-7711-7933-4 (pdf) ISBN: 978-0-7711-7935-8 (print) 1. Judaism—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 2. Religion—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 3. Multiculturalism—Study and teaching (Secondary) --Manitoba. 4. Spirituality – Study and teaching (Secondary) – Manitoba. 5. Religion and culture – Study and teaching (Secondary) -- Manitoba. I. Manitoba. Manitoba Education. 379.28 Copyright © 2019, the Government of Manitoba, represented by the Minister of Education. Manitoba Education Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Manitoba Education. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Sincere thanks to the authors, artists, and publishers who allowed their original material to be used. All images found in this resource are copyright protected and should not be extracted, accessed, or reproduced for any purpose other than for their intended educational use in this resource. Any websites referenced in this resource are subject to change without notice. Educators are advised to preview and evaluate websites and online resources before recommending them for student use. Print copies of this resource (stock number 80750) can be purchased from the Manitoba Learning Resource Centre. -

The Jews: Their Origins, in America, in Connecticut. a Curriculum Guide

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 217 108 UD 022 286 AUTHOR Klitz, Sally Innis TITLE The Jews: Their Origins, in America, in Connecticut. A Curriculum Guide. The Peoples of Connecticut Multicultural Ethnic Heritage Series No. 3. Second Edition. INSTITUTION Connecticut Univ., Storrs. Thut (I.N.) World Education Center. SPONS AGENCY Aetna Life and Casualty, Hartford, Conn.; Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-918158-08 PUB DATE 80 NOTE 153p.; Original publication costs supported in part by the Hartford Jewish Federation and the Connecticut State Department of Education. Not available in paper copy due to institution's restrictions. For a related document, see ED 160 487._ AVAILABLE FRO), 'lliversity of Connecticut, The I.N. Thut World Education Center, Box U-32, Storrs, CT 06268 ($4.00 plus $0.80 postage). EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Acculturation; *Cultural Background; European History; Immigrants; Instructional Materials; *Jews; *Judaism; *Political Influences; *Religious Cultural Groups; Secondary Education; *Sociocultural Patterns; United States History IDENTIFIERS Connecticut ABSTRACT This curriculum guide explores the Jewish ethnic and religious community in the United States generally, and specifically in Connecticut. Intended as a resource tool for studying the Jewish cultural heritage and traditions, the material may be used among Jews and non-Jews. The guide is divided into three parts. Part one is a detailed account of Jewish religious and political history. Part two contains information on the history of Jewish immigration to the United States; the assimilation of Jews into American society; the impact of Jewish culture and religion in American history; and the development of the Jewish cultural community within a pluralistic society. -

Theatretalk: (In)Justice

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2020 TheatreTalk: (In)Justice Meghan Baker Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Meghan, "TheatreTalk: (In)Justice" (2020). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 379. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/379 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Theatre Talk: (In)Justice Creating Critical Thinking and Conversation Through Methods of Performance using Fiddler on the Roof as an example Meghan Baker Advisor: John Bower Theatre, Performance, and Activism Art is inherently political and no art, in my opinion, is better suited to activism than performance. I personally believe that theatre is one of the greatest vehicles for developing critical social change and cultivating conversation around issues of injustice. For me, there is something uniquely captivating about the power of people sharing a space and watching a live performance. It has the potential to be an extremely productive way to communicate a message, while also creating a secure space for audience members to critically engage with the subject or material and step into other people’s stories. Fostering a safe environment for children to participate in this process not only allows them to develop compassion and awareness from an early age, but gives them the opportunity to increase artistic, imaginative, social, and problem-solving skills. -

Judaism Intellectual Output 2, Unit III

Judaism Intellectual Output 2, Unit III The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Version No. Author, institution Date/Last Update 2 - Renaud Rochette, Institut européen en sciences des 07/05/2018 religions – Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, PSL IERS Digital Modules on Judaism • Introduction to Judaism I: History of Judaism • Introduction to Judaism II: Themes Judaism is a monotheistic religion, stemming from the covenant established by God with the Hebrews. The origins of Judaism According to the Bible, Abraham acknowledged God as the one true God and rejected idolatry. However, historical studies tend to show that the emergence of monotheism is a much slower process. Nevertheless, the religion of the Hebrews is the first monotheistic religion. More information on: • The origins of Judaism Main doctrinal tenets of Judaism Judaism is sometimes described as an orthopraxy, i.e. practices and observances are more important than belief. It is based on the principles written in the Hebrew Bible (the Tanakh) and its commentaries, such as the Talmud. 1. The scrolls of the Torah contain the Jewish law (see IERS module Judaism II, section 1, source 1) More information on: • The Hebrew Bible and its commentaries 2 Main practices of Judaism Abiding by the religious law is a way of worshipping God and maintaining the Covenant. Two of the most known practices are the day of rest (Shabbat) and the kashrut, a complex set of dietary laws. -

The Ancient Hebrews and the Origins of Judaism 11.1 Introduction in Chapter 10, You Learned About Egypt's Southern Neighbor, the African Kingdom of Kush

')! X warn MU f£53MM\3?MJ XI ' ^E? CHAPTER 4 Moses presents theTen Commandments, setting forth the laws of Judaism. The Ancient Hebrews and the Origins of Judaism 11.1 Introduction In Chapter 10, you learned about Egypt's southern neighbor, the African kingdom of Kush. In this chapter, you will learn about a group of people who lived northeast of Egypt: the Hebrews. The Hebrew civilization developed gradually after 1800 B.C.E. and flourished until 70 C.E. The people who became the Hebrews originally lived in Mesopotamia. Around 1950 B.C.E., they moved to the land of Canaan (modern-day Israel). The Hebrews were the founders of Judaism, one of the world's major religions. As you will learn in the next chapter, the Hebrews eventu- ally became known as the Jews. Judaism is the Jewish religion. The origins of Judaism and its basic laws are recorded in its most sacred text, the Torah. The word Torah means "God's teaching." The Torah consists of the first five books of the Jewish Bible. (Christians refer to the Jewish Bible as the Old Testament.) In this chapter, you will read about some of the early history of the Jewish people told in the Bible. You will meet four Hebrew leaders —Abraham, Moses, and kings David and Solomon—and learn about their contributions to the development of Judaism. The Ancient Hebrews and the Origins of Judaism 101 11.2 What We Know About the Ancient Hebrews Historians rely on many artifacts to learn about the ancient Hebrews and their time, including the Torah. -

Reading List for Teaching an Introductory Course on the Emergence of Judaism Christine Hayes

Reading List for Teaching an Introductory Course on The Emergence of Judaism Christine Hayes In compiling this reading list I have chosen to focus on books that provide more than a good introduction to the history, society, culture, literature and major ideas of biblical Israel and rabbinic Judaism in their broader context. I have also included works that deal in a relatively self-conscious way with the transition from biblical Israel to rabbinic Judaism. It is almost inevitable that a reading list of this sort will be somewhat idiosyncratic. Nevertheless, these works are particularly complementary to The Emergence of Judaism and serve non-specialists in the field. The list ends with reference works that the non-specialist can consult as the need might arise. Overviews of Jewish History, Judaism and/or classic Jewish texts: Holtz, Barry. Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts. New York: Summit Books, 1984. An essential and superb introduction to the classic texts of Jewish tradition: the Hebrew Bible, Rabbinic literature, medieval Bible commentaries, medieval philosophical works, Kabbalistic texts, Hasidic writings and the prayer book. Aimed at the non-expert with excellent suggestions for future study. Scheindlin, Raymond P. A Short History of the Jewish People: From Legendary Times to Modern Statehood. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000. An overview of Jewish history that focuses on the major geographical, cultural and political forces that have shaped Jewish history and emphasizes the interaction of Jews with the nations and cultures among whom they have lived. Seltzer, Robert. Jewish People, Jewish Thought: The Jewish Experience in History. -

Judaic Studies 1

Judaic Studies 1 perspective on Judaic Studies as an interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary field Judaic Studies of study concerned with Jews and Judaism over three millennia of history. 4a. Historical breadth requirement: Students primarily studying the premodern period must enroll in at least one course in the modern Director period, and students whose primary focus is the modern period must enroll in at least one class in the premodern period. Saul Olyan Some examples of recent courses that focus on the modern period The Program in Judaic Studies is dedicated to the study of Jewish history, literature, language, politics and religions. Offering an interdisciplinary • JUDS 0050H Israel's Wars undergraduate concentration, the program provides students with the • JUDS 0066 The Lower East Side and Beyond: American opportunity to explore Jewish culture and civilization across the ages. Jewish History 1880-2000 Since Christianity and Islam have deep roots in Judaism, and the Western • JUDS 0902 History of the Holocaust world has been profoundly shaped by a deep and abiding tension with • JUDS 1753 Blacks and Jews in American History and both Jewish religious tradition and the Jewish communities in its midst, Culture the concentration puts particular importance on studying the interactions Some examples of recent courses that focus on the pre-modern of Jews and non-Jews in both ancient and modern periods. The history period: and culture of the State of Israel and its place in the Middle East is also a major focus of study. These are all issues with significant contemporary • JUDS 0670 War and Peace in the Hebrew Bible and its resonance, so the concentration offers its students many new insights on Environment the world in which we live. -

Religions-11-00085-V2.Pdf

religions Article The Samaritan and Jewish Versions of the Pentateuch: A Survey Ingrid Hjelm Faculty of Theology, University of Copenhagen, 1165 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] Received: 15 November 2019; Accepted: 6 February 2020; Published: 12 February 2020 Abstract: This article discusses the main differences between the Samaritan and the Jewish versions of the Pentateuch. The Samaritan Bible consists of the Torah—that is, the Five Books of Moses—also called the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP). The Jewish Bible contains in addition the Prophets and the Writings, a total of 39 books. The introduction seeks to present both traditions in their own right and in relation to other ancient textual traditions (the Dead Sea Scrolls, the ancient Greek and Latin, and the Septuagint). The focus of this article is on the shared tradition of the Pentateuch with special emphasis on the textual and theological character of the Samaritan Pentateuch: major variants in the SP, the Moses Layer, and the cult place. This article closes with discussion of editions and translations of the Samaritan Bible and the Masoretic Bible respectively. Keywords: Samaritan Pentateuch; Jewish Masoretic Bible; variant traditions; Moses; cult place; editions and translations 1. Introduction The Samaritan, Jewish and Christian Canons differ in regard to the number of books included. The Samaritan canon consists only of the Five Books of Moses, which is the Torah (Law) and by scholars called the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP). These books also form part of the Jewish canon, which we call the Hebrew Bible (HB), the Masoretic Tradition (MT) or the TaNaK. In addition to the Law (Torah), the Hebrew Bible also contains the Prophets (Neviim) and the Writings (Ketuvim)—a total of 24 books (4 Ezra 14:45) or 22 books (Josephus, Against Apion, 1.38) in ancient counting.