Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012

Understanding the Major Branches of Modern Judaism May 10, 2012 Initial terms: 24 or 72 kinds Torah/Talmud (oral/written law).Halacha orthopraxy/orthodoxy, haskalah Babylonian Talmud kabbalah, Sephardic, Ashkenazi (with material gleaned from Wikipedia articles- no access to my books yet) Modern Judaism is loosely broken into three main branches: Orthodox Judaism is the approach to Judaism which adheres to the traditional interpretation and application of the laws and ethics of the Torah as legislated in the Talmudic texts by the Sanhedrin ("Oral Torah") and subsequently developed and applied by the later authorities known as the Gaonim, Rishonim, and Acharonim. Orthodox Jews are also called "observant Jews"; Orthodoxy is known also as "Torah Judaism" or "traditional Judaism". Orthodox Judaism generally refers to Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism (Chasidic Chabad) but can actually include a wide range of beliefs. Orthodoxy collectively considers itself the only true heir to the Jewish tradition. The Orthodox Jewish movements generally consider all non-Orthodox Jewish movements to be unacceptable deviations from authentic Judaism; both because of other denominations' doubt concerning the verbal revelation of Written and Oral Torah, and because of their rejection of Halakhic precedent as binding. As such, Orthodox groups characterize non-Orthodox forms of Judaism as heretical Reform Judaism is a phrase that refers to various beliefs, practices and organizations associated with the Reform Jewish movement in North America, the United Kingdom and elsewhere.[1] In general, Reform Judaism maintains that Judaism and Jewish traditions should be modernized and compatible with participation in the surrounding culture. Many branches of Reform Judaism hold that Jewish law should be interpreted as a set of general guidelines rather than as a list of restrictions whose literal observance is required of all Jews.[2][3] Similar movements that are also occasionally called "Reform" include the Israeli Progressive Movement and its worldwide counterpart. -

Adas Israel Congregation

Adas Israel Congregation December/Kislev–Tevet Highlights: ChronicleZionism 4.0: The Future Relationship between Israel and World Jewry 3 Combined Community Shabbat Service 3 Happy Hanukkah 5 December MakomDC 7 Ma Tovu: Sharon Blumenthal Cohen & Dan Cohen 20 Scenes From This Year’s Anne Frank House Mini-Walk 21 Chronicle • December 2016 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt “Our Rabbis taught: The mitzvah of Hanukkah is for a person to light (the candles) for his household; the zealous [kindle] a light for each member [of the household]; and the extremely zealous, Beit Shammai maintains: On the first day eight lights are lit and thereafter they are gradually reduced; but Beit Hillel says: On the first day one is lit and thereafter they are progressively increased.” Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 21b Hanukkah, Christmas, and Kwanzaa overlap As we approach the holiday of Hanukkah it is helpful to remember the this year—what an opportunity to create different traditions of lighting the hanukkiyah/ot in each household. The a season of good will and light for all of us. Talmud teaches us that it is enough for one to light a candle each night of Certainly as a country, we need to find our Hanukkah, but the more fervent among us have each family member of the common values and reunite. As Americans household light his or her own candles each night. Since we follow the way and Jews, we share a belief in the example of Beit Hillel, each night we increase the number of candles we light, thereby we serve for the nations of the world. -

M E O R O T a Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (Formerly Edah Journal)

M e o r o t A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly Edah Journal) Tishrei 5770 Special Edition on Modern Orthodox Education CONTENTS Editor’s Introduction to Special Tishrei 5770 Edition Nathaniel Helfgot SYMPOSIUM On Modern Orthodox Day School Education Scot A. Berman, Todd Berman, Shlomo (Myles) Brody, Yitzchak Etshalom,Yoel Finkelman, David Flatto Zvi Grumet, Naftali Harcsztark, Rivka Kahan, Miriam Reisler, Jeremy Savitsky ARTICLES What Should a Yeshiva High School Graduate Know, Value and Be Able to Do? Moshe Sokolow Responses by Jack Bieler, Yaakov Blau, Erica Brown, Aaron Frank, Mark Gottlieb The Economics of Jewish Education The Tuition Hole: How We Dug It and How to Begin Digging Out of It Allen Friedman The Economic Crisis and Jewish Education Saul Zucker Striving for Cognitive Excellence Jack Nahmod To Teach Tsni’ut with Tsni’ut Meorot 7:2 Tishrei 5770 Tamar Biala A Publication of Yeshivat Chovevei Torah REVIEW ESSAY Rabbinical School © 2009 Life Values and Intimacy Education: Health Education for the Jewish School, Yocheved Debow and Anna Woloski-Wruble, eds. Jeffrey Kobrin STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Meorot: A Forum of Modern Orthodox Discourse (formerly The Edah Journal) Statement of Purpose Meorot is a forum for discussion of Orthodox Judaism’s engagement with modernity, published by Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School. It is the conviction of Meorot that this discourse is vital to nurturing the spiritual and religious experiences of Modern Orthodox Jews. Committed to the norms of halakhah and Torah, Meorot is dedicated -

I. Maot Chitim II. Ta'anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns III. Chametz

To The Brandeis Community, Many of us have fond memories of preparing for the holiday of Pesach (Passover), and our family's celebration of the holiday. Below is a basic outline of the major halakhic issues for Pesach this year. If anyone has questions they should be in touch with me at h[email protected]. In addition to these guidelines, a number of resources are available online from the major kashrut agencies: ● Orthodox Union: http://oukosher.org/passover/ ○ a pdf of the glossy magazine that’s been seen around campus can be found here ● Chicago Rabbinical Council: link ● Star-K: link Best wishes for a Chag Kasher ve-Sameach, Rabbi David, Ariel, Havivi, and Tiffy Pardo Please note: Since we are all spending Pesach all over the world (literally...I’m selling your chametz for you, I know) please use the internet to get appropriate halakhic times. I recommend m yzmanim.com or the really nifty sidebar on https://oukosher.org/passover/ I. Maot Chitim The Rema (Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayim 429) records the ancient custom of ma'ot chitim – providing money for poor people to buy matzah and other supplies for Pesach. A number of tzedka organizations have special Maot Chitim drives. II. Ta’anit Bechorim, Fast of the Firstborns Erev Pesach is the fast of the firstborns, to commemorate the fact that the Jewish firstborns were spared during m akat bechorot (the slaying of the firstborns). This year the fast is observed on Friday April 3 (14 Nissan) beginning at alot hashachar (i.e. -

Print Friendly Version

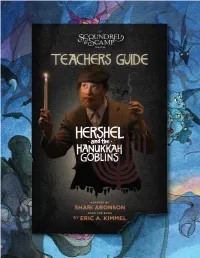

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 The Holiday of Hanukkah 5 Judaism and the Jewish Diaspora 8 Ashkenazi Jews and Yiddish 9 Latkes! 10 Pickles! 11 Body Mapping 12 Becoming the Light 13 The Nigun 14 Reflections with Playwright Shari Aronson 15 Interview with Author Eric Kimmel 17 Glossary 18 Bibliography Using the Guide Welcome, Teachers! This guide is intended as a supplement to the Scoundrel and Scamp’s production of Hershel & The Hanukkah Goblins. Please note that words bolded in the guide are vocabulary that are listed and defined at the end of the guide. 2 Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins Teachers Guide | The Scoundrel & Scamp Theatre The Holiday of Hanukkah Introduction to Hanukkah Questions: In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah means inauguration, dedication, 1. What comes to your mind first or consecration. It is a less important Jewish holiday than others, when you think about Hanukkah? but has become popular over the years because of its proximity to Christmas which has influenced some aspects of the holiday. 2. Have you ever participated in a Hanukkah tells the story of a military victory and the miracle that Hanukkah celebration? What do happened more than 2,000 years ago in the province of Judea, you remember the most about it? now known as Palestine. At that time, Jews were forced to give up the study of the Torah, their holy book, under the threat of death 3. It is traditional on Hanukkah to as their synagogues were taken over and destroyed. A group of eat cheese and foods fried in oil. fighters resisted and defeated this army, cleaned and took back Do you eat cheese or fried foods? their synagogue, and re-lit the menorah (a ceremonial lamp) with If so, what are your favorite kinds? oil that should have only lasted for one night but that lasted for eight nights instead. -

We Arrived in Manipur Unannounced, to Get a Bona Fide Glimpse Into How

ESENT I PR AR D N A To see our subscription options, I R please click on the Mishpacha tab A e knocked and waited nervously mesor ah because we hadn’t notified them ahead — yet we weren’t disappointed. Quest As the door opened to the little hut, a kippah-clad man smiled broadly and Wsaid, “Baruch haba!” He led us through a courtyard to a small, well-kept synagogue. We were not in Monsey, but in a far-fl ung corner of India on the northeastern border state of Manipur, preparing the ground in advance of our curious delegation — a party of 35 Western Jews and one of the rare groups to visit this little-known Indian com- munity known as the Bnei Menashe. We were both excited and relieved by the warm wel- come, as their story is exotic and spans thousands of years of Jewish history. It is a direct link with our Biblical past and raises interesting halachic and philosophic conun- drums about our future. Welcome to our search for part of the Ten Lost Tribes. It all started with a call from the OU Israel Center in- viting us to lead a “Halachic Adventure” tour. We asked the organizers where they would like to go, and they re- plied, “Where would you like to lead us?” The answer for us was simple: to return to India where the richness and diversity of Jewish history is largely unknown to much of the Jewish world. Our goal was to give our fellow adventurers a unique, exciting, and o -the-beaten-track experience. -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

1 ETHNICITY and JEWISH IDENTITY in JOSEPHUS by DAVID

ETHNICITY AND JEWISH IDENTITY IN JOSEPHUS By DAVID McCLISTER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 David McClister 2 To the memory of my father, Dorval L. McClister, who instilled in me a love of learning; to the memory of Dr. Phil Roberts, my esteemed colleague; and to my wife, Lisa, without whose support this dissertation, or much else that I do, would not have been possible. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I gladly recognize my supervisory committee chair (Dr. Konstantinos Kapparis, Associate Professor in the Classics Department at the University of Florida). I also wish to thank the other supervisory commiteee members (Dr. Jennifer Rea, Dr. Gareth Schmeling, and Dr. Gwynn Kessler as a reader from the Religious Studies Department). It is an honor to have their contributions and to work under their guidance. I also wish to thank the library staff at the University of Florida and at Florida College (especially Ashley Barlar) who did their work so well and retrieved the research materials necessary for this project. I also wish to thank my family for their patient indulgence as I have robbed them of time to give attention to the work necessary to pursue my academic interests. BWGRKL [Greek] Postscript® Type 1 and TrueTypeT font Copyright © 1994-2006 BibleWorks, LLC. All rights reserved. These Biblical Greek and Hebrew fonts are used with permission and are from BibleWorks, software for Biblical -

Kehilath Jeshurun Bulletin

RICHARD JOEL TO ADDRESS ANNUAL MEETING (See Page 3) Kehilath Jeshurun Bulletin Volume LXXIII, Number 5 March 29, 2004 7 Nisan 5764 CYNTHIA K. APRIL ANNUAL SYNAGOGUE SHABBATON April 2 - 3, 2004 SHABBAT SCHOLAR Friday Evening Dinner: “TO ACQUIRE A WIFE: RABBI DOV LINZER MARRIAGE AS ACQUISITION Rosh HaYeshiva OR AS KIDDUSHIN” At Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Saturday Morning: Rabbinical School “CHRISTIANITY AND ISLAM: IDOLATRY?” FRIDAY DINNER AND SATURDAY LUNCH — SHABBAT BEFORE PASSOVER (THIS MEANS NO COOKING FOR YOU!) Two Meals Members: Non-Members: Adult $60 Adult $70 Junior $50 Junior $60 Child $30 Child $50 Deadline: Wednesday, March 31 Space Permitting YOM HASHOAH SERVICE HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE DAY Sunday, April 18, 7:00 PM "THE CHANGING FACE OF ANTI-SEMITISM: HOW FAR HAVE WE COME?” ABRAHAM FOXMAN National Director of the Anti-Defamation League The program will begin with a candle lighting and to indicate their participation. Ma’ariv, readings ceremony by survivors and second, third, and fourth for a Holocaust Service, appropriate songs by the generation participants. Those who fit into these Ramaz Middle School Chorus and poems written categories are urged to call Event Co-Chair Caroline about the Shoah by students of the Ramaz Middle Massel at 212-861-7178 to inform us of their history School will complete the evening. Page 2 KEHILATH JESHURUN BULLETIN SUE ROBINS AND ELISA LUNZER TO RECEIVE SECOND ANNUAL JUDITH KAUFMAN HURWICH KETER TORAH AWARDS ON SHAVUOT The Officers and Executive Committee of the congregation are pleased to announce that the Second Annual Judith Kaufman Hurwich Keter Torah Awards will be presented to Sue Robins and Elisa Lunzer on the second day of Shavuot. -

Living Judaism: an Introduction to Jewish Belief and Practice Rabbi Adam Rubin, Ph.D

Living Judaism: An Introduction to Jewish Belief and Practice Rabbi Adam Rubin, Ph.D. – Beth Tikvah Congregation Syllabus 5779 (2018‐19) “I am a Jew because...” Edmund Fleg (France, 1874‐1963) I am a Jew because Judaism demands no abdication of the mind. I am a Jew because Judaism asks every possible sacrifice of my life. I am a Jew because Wherever there are tears and suffering the Jew weeps. I am a Jew because Whenever the cry of despair is heard the Jew hopes. I am a Jew because The message of Judaism is the oldest and the newest. I am a Jew because The promise of Judaism is a universal promise. I am a Jew because For the Jew, the world is not finished; human beings will complete it. I am a Jew because For the Jew, humanity is not finished; we are still creating humanity. I am a Jew because Judaism places human dignity above all things, even Judaism itself. I am a Jew because Judaism places human dignity within the oneness of God. Rabbi Adam Rubin 604‐306‐1194 [email protected] B’ruchim haba’im! Welcome to a year of “Living Judaism.” As a community of learners and as individuals we are setting out on a journey of discovery that will involve two important characteristics of Judaism, joy and wrestling. During this journey we will explore the depth and richness of the Jewish Living Judaism 5779 (2018-2019) Syllabus Page 1 of 7 way of life, open our minds and spirits to the traditions that have been passed down, and honour those traditions with our hard questions and creative responses to them. -

The Zamir Chorale of Boston Joshua R

The Zamir Chorale of Boston Joshua R. Jacobson, Artistic Director Barbara Gaffin, Managing Director Lawrence E. Sandberg, Concert Manager and Merchandise Manager Edwin Swanborn, Accompanist Andrew Mattfeld, Assistant Conductor Devin Lawrence, Assistant to the Conductor Jacob Harris and Melanie Blatt, Conducting Interns Rachel Miller, President Charna Westervelt, Vice President Michael Kronenberg, Librarian Sopranos Betty Bauman* • Melanie Blatt • Jenn Boyle • Vera Broekhuysen • Lisa Doob • Sharon Goldstein • Naomi Gurt Lind • Maayan Harel • Marilyn J. Jaye • Anne Levy • Sharon Shore Rachel Slusky • Julie Kopp Smily • Louise Treitman • Deborah Wollner Altos Anna Adler • Sarah Boling • Jamie Chelel • Johanna Ehrmann • Deborah Melkin* • Rachel Miller • Judy Pike • Jill Sandberg • Nancy Sargon-Zarsky • Rachel Seliber • Elyse Seltzer • Gail Terman • Phyllis Werlin • Charna Westervelt • Phyllis Sogg Wilner Tenors David Burns • Steven Ebstein* • Suzanne Goldman • Jacob Harris • Kevin Martin • Andrew Mattfeld* • Dan Nesson • Leila Joy Rosenthal • Lawrence E. Sandberg • Gilbert Schiffer • Dan Seltzer • Yishai Sered • Andrew Stitcher Basses Peter Bronk • Abba Caspi • Phil Goldman • Michael Krause-Grosman • Michael Kronenberg Devin Lawrence* • Richard Lustig • Michael Miller • James Rosenzweig • Peter Squires • Mark Stepner • Kyler Taustin • Michael Victor • Jordan Lee Wagner • Robert Wright • Richard Yospin *Section Leader Board of Directors 2016–17 Joshua Jacobson, President • Robert Snyder, Chairman • Peter Finn, Clerk • Gilbert Schiffer, Treasurer • Richard Blocker • Bruce Creditor • Bruce Donoff • Barbara Gaffin, Managing Director • Rachel Miller, Chorus President • Lawrence E. Sandberg Program Notes PSALMS What book has ever been set to music more often than the book of Psalms? Jews and Christians have been interpreting these 150 songs (and they were originally songs, not poems) for thousands of years—as Gregorian chant, synagogue Psalmody, catchy Hallel tunes, stately hymns, and musical masterworks.