Theatretalk: (In)Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60628-8 - The Origins of Judaism: From Canaan to the Rise of Islam Robert Goldenberg Excerpt More information A Note of Introduction this book tells the story of the emergence of judaism out of its biblical roots, a story that took well over a thousand years to run its course. When this book begins there is no “Judaism” and there is no “Jewish people.” By the end, the Jews and Judaism are everywhere in the Roman Empire and beyond, more or less adjusted to the rise of Christianity and ready to absorb the sudden appearance of yet another new religion called Islam. It may be useful to provide a few words of introduction about the name Judaism itself. This book will begin with the religious beliefs and practices of a set of ancient tribes that eventually combined to form a nation called the Children of Israel. Each tribe lived in a territory that was called by its tribal name: the land of Benjamin, the land of Judah, and so on. According to the biblical narrative, these tribes organized and maintained a unified kingdom for most of the tenth century BCE, but then the single tribe of Judah was separated from the others in a kingdom of its own, called the Kingdom of Judah (in Hebrew yehudah) to distinguish it from the larger Kingdom of Israel to its north. Thus the name Israel was essentially a national or ethnic designation, while the name Judah simultaneously meant a smaller ethnic entity, included within the larger one, and the land where that group dwelt for hundreds of years. -

ARTICLES Israel's Migration Balance

ARTICLES Israel’s Migration Balance Demography, Politics, and Ideology Ian S. Lustick Abstract: As a state founded on Jewish immigration and the absorp- tion of immigration, what are the ideological and political implications for Israel of a zero or negative migration balance? By closely examining data on immigration and emigration, trends with regard to the migration balance are established. This article pays particular attention to the ways in which Israelis from different political perspectives have portrayed the question of the migration balance and to the relationship between a declining migration balance and the re-emergence of the “demographic problem” as a political, cultural, and psychological reality of enormous resonance for Jewish Israelis. Conclusions are drawn about the relation- ship between Israel’s anxious re-engagement with the demographic problem and its responses to Iran’s nuclear program, the unintended con- sequences of encouraging programs of “flexible aliyah,” and the intense debate over the conversion of non-Jewish non-Arab Israelis. KEYWORDS: aliyah, demographic problem, emigration, immigration, Israel, migration balance, yeridah, Zionism Changing Approaches to Aliyah and Yeridah Aliyah, the migration of Jews to Israel from their previous homes in the diaspora, was the central plank and raison d’être of classical Zionism. Every stream of Zionist ideology has emphasized the return of Jews to what is declared as their once and future homeland. Every Zionist political party; every institution of the Zionist movement; every Israeli government; and most Israeli political parties, from 1948 to the present, have given pride of place to their commitments to aliyah and immigrant absorption. For example, the official list of ten “policy guidelines” of Israel’s 32nd Israel Studies Review, Volume 26, Issue 1, Summer 2011: 33–65 © Association for Israel Studies doi: 10.3167/isr.2011.260108 34 | Ian S. -

Torah: Covenant and Constitution

Judaism Torah: Covenant and Constitution Torah: Covenant and Constitution Summary: The Torah, the central Jewish scripture, provides Judaism with its history, theology, and a framework for ethics and practice. Torah technically refers to the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). However, it colloquially refers to all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, also called the Tanakh. Torah is the one Hebrew word that may provide the best lens into the Jewish tradition. Meaning literally “instruction” or “guidebook,” the Torah is the central text of Judaism. It refers specifically to the first five books of the Bible called the Pentateuch, traditionally thought to be penned by the early Hebrew prophet Moses. More generally, however, torah (no capitalization) is often used to refer to all of Jewish sacred literature, learning, and law. It is the Jewish way. According to the Jewish rabbinic tradition, the Torah is God’s blueprint for the creation of the universe. As such, all knowledge and wisdom is contained within it. One need only “turn it and turn it,” as the rabbis say in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 5:25, to reveal its unending truth. Another classical rabbinic image of the Torah, taken from the Book of Proverbs 3:18, is that of a nourishing “tree of life,” a support and a salve to those who hold fast to it. Others speak of Torah as the expression of the covenant (brit) given by God to the Jewish people. Practically, Torah is the constitution of the Jewish people, the historical record of origins and the basic legal document passed down from the ancient Israelites to the present day. -

Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20Th Century

Name Date Migration of Jews to Palestine in the 20th Century Read the text below. The Jewish people historically defined themselves as the Jewish Diaspora, a group of people living in exile. Their traditional homeland was Palestine, a geographic region on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. Jewish leaders trace the source of the Jewish Diaspora to the Roman occupation of Palestine (then called Judea) in the 1st century CE. Fleeing the occupation, most Jews immigrated to Europe. Over the centuries, Jews began to slowly immigrate back to Palestine. Beginning in the 1200s, Jewish people were expelled from England, France, and central Europe. Most resettled in Russia and Eastern Europe, mainly Poland. A small population, however, immigrated to Palestine. In 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella expelled all Jewish people living in Spain, some refugees settled in Palestine. At the turn of the 20th century, European Jews were migrating to Palestine in large numbers, fleeing religious persecution. In Russia, Jewish people were segregated into an area along the country’s western border, called the Pale of Settlement. In 1881, Russians began mass killings of Jews. The mass killings, called pogroms, caused many Jews to flee Russia and settle in Palestine. Prejudice against Jews, called anti-Semitism, was very strong in Germany, Austria-Hungary, and France. In 1894, a French army officer named Alfred Dreyfus was falsely accused of treason against the French government. Dreyfus, who was Jewish, was imprisoned for five years and tried again even after new information proved his innocence. The incident, called The Dreyfus Affair, exposed widespread anti-Semitism in Western Europe. -

FFYS 1000.03 – the Holy Land and Jerusalem: a Religious History

First Year Seminar Loyola Marymount University FFYS 1000.03 – The Holy Land and Jerusalem: A Religious History Fall 2013 | T/R 8:00 – 9:15 AM | Classroom: University Hall 3304 Professor: Gil Klein, Ph.D. | Office hours: W 1:30-3:00 PM; T/R 3:30 - 5:00 PM and by appointment Office: UH 3775 | Phone: (310) 338 1732 | Email: [email protected] Writing instructor: Andrew (AJ) Ogilvie, Ph.D. Candidate, UC Santa Barbara Email: [email protected] Course description The Holy Land, with the city of Jerusalem at its center, is where many of the foundational moments in Judaism, Christianity and Islam have occurred. As such, it has become a rich and highly contested religious symbol, which is understood by many as embodying a unique kind of sanctity. What makes it sacred? What led people in different periods to give their life fighting over it? How did it become the object of longing and the subject of numerous works of religious art and literature? What is the secret of the persistent hold it still has on the minds of Jews, Christians and Muslims around the world? This course will explore central moments in the religious history of the Holy Land from ancient times to the present day in an attempt to answer some of these questions. It will do so through the critical analysis of religious text, art and architecture, as well as through the investigation of contemporary culture and politics relating to the Holy Land and Jerusalem. Course structure The structure of this course is based on the historical transformations of the Holy Land and Jerusalem from ancient through modern times, as well as on the main cultural aspects of their development. -

Robert Aaron Kenedy / the New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic 8 Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal

Robert Aaron Kenedy / The New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic 8 Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal Robert Aaron Kenedy The New Anti-Semitism and Diasporic Liminality: Jewish Identity from France to Montreal Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 25, 2017 9 Through a case study approach, 40 French Jews were interviewed revealing their primary reason for leaving France and resettling in Montreal was the continuous threat associated with the new anti-Semitism. The focus for many who participated in this research was the anti-Jewish sentiment in France and the result of being in a liminal diasporic state of feeling as though they belong elsewhere, possibly in France, to where they want to return, or moving on to other destinations. Multiple centred Jewish and Francophone identities were themes that emerged throughout the interviews. There have been few accounts of the post-1999 French Jewish diaspora and reset- tlement in Canada. There are some scholarly works in the literature, though apart from journalistic reports, there is little information about this diaspora.1 Carol Off’s (2005) CBC documentary entitled One is too Many: Anti-Semitism on the Rise in Eu- rope highlights the new anti-Semitism in France and the outcome of Jews leaving for Canada. The documentary also considers why a very successful segment of Jews would want to leave France, a country in which they have felt relatively secure since the end of the Second World War. This documentary and media reports of French Jews leaving France for destinations such as Canada provided the inspiration for beginning an in-depth case study to investigate why Jews left France and decided to settle in Canada. -

Judaism Practices Importance of the Synagogue • This Is the Place

Ms Caden St Michael’s Catholic College R.E. Department Revision- Judaism Practices rabbi and a pulpit where sermons are delivered. Importance of the Synagogue The Ark (Aron Hakodesh)- this is This is the place where Jewish the holiest place in the Synagogue. people meet for prayer, worship and They believed that the original ark study. They believe that any prayer contained stone tablet s that God can only take place where there are gave to Moses at Sinai. In at least 10 adults. Synagogues, Jews are reminded of Synagogues are usually rectangular the original ark. It is at the front of shaped but there are no specific the Synagogue facing Jerusalem. rules about its size and decoration. There are usually steps up to the It is common for there to be a stain- Ark to remind them that God and glassed window representing the the Torah are more important and Star of David. sacred. The ark is only opened during The synagogue is the central point special prayers and when it’s read for life as a Jewish community- it is during services. where many rites of passages take Ever-Burning Light (Ner Tamid)- place. This symbolises God’s presence and a It is important as a place of study reminder of the Menorah that was e.g. it is where a young boy/girl will lit every night in the Temple. learn Hebrew and study the Torah in Reading Platform (bimah)- This is a preparation for their bar/bat raised platform which is usually in mitzvahs. the very centre- it is used for Questions: reading from the Torah and becomes the focus of worship. -

The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction in the Last Chapter, You Read About the Origins of Judaism

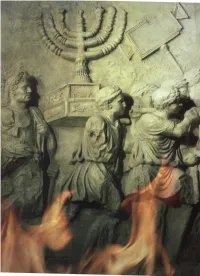

CHAPTER 4 Roman soldiers destroy theTemple of Jerusalem and carry off sacred treasures. The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you read about the origins of Judaism. In this chapter, you will discover how Judaism was preserved even after the Hebrews lost their homeland. As you have learned, the Hebrew kingdom split in two after the death of King Solomon. Weakened by this division, the Hebrews were less able to fight off invaders. The northern kingdom of Israel was the first to fall. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered Israel. The kingdom's leaders were carried off to Mesopotamia. In 597 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was invaded by another Meso- potamian power, Babylon. King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon laid siege to the city of Jerusalem. The Hebrews fought off the siege until their food ran out. With the people starving, the Babylonians broke through the walls and captured the city. In 586 B.C.E., Nebuchadrezzar burned down Solomon's great Temple of Jerusalem and all the houses in the city. Most of the people of Judah were taken as captives to Babylon. The captivity in Babylon was the begin- ning of the Jewish Diaspora. The word diaspora means "a scattering." Never again would most of the followers of Judaism be together in a single homeland. Yet the Jews, as they came to be known, were able to keep Judaism alive. In this chapter, you will first learn about four important Jewish beliefs. Then you will read about the Jews' struggle to preserve Judaism after they had been forced to settle in many lands. -

Name: Date: H.W.#: ___My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and The

Name: _____________________________ Date: __________________ H.W.#: ______ My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and the Jewish People” Section 1 – The Origins of Judaism ! Terms to understand when reading: 1. Jews – a group of people who share the same religious and cultural beliefs in God and worship following an ancient text known as the Torah. In ancient days, Jews were also known as the Hebrews and Israelites. Many Hebrews traveled from Canaan to Egypt to escape poverty, only to be enslaved by the Pharaohs. One of their leaders named Moses helped to free them from captivity in Egypt and led them back into Canaan (see the map) to an area that was to become known as the Jewish Promised Land. This land would later be called Judah, and much later known as Israel. In modern times, the ancient land of Canaan is now divided between Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Palestine. 2. monotheism - belief in one God. Jews, along with several other religions, believe that there is only one divine spirit who can be worshiped. In ancient times, the Hebrew God was sometimes referred to as Jehovah or Yahweh. Judaism, as a faith, is one of the world’s oldest religions and it said to date back at least 3000 years. (Some theologians place the religion’s date of origin closer to 4000 years.) 3. ethics - Simply put, ethics help to guide individuals from understanding right from wrong. The teaching of ethical principals is the foundation for most religions, including Judaism. In Judaism, as well as Christianity, the ethics of the religion and culture are clearly mapped out in the commandments. -

Guide to Reading Nevi'im and Ketuvim" Serves a Dual Purpose: (1) It Gives You an Overall Picture, a Sort of Textual Snapshot, of the Book You Are Reading

A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim By Seth (Avi) Kadish Contents (All materials are in Hebrew only unless otherwise noted.) Midrash Introduction (English) How to Use the Guide Sheets (English) Month 1: Yehoshua & Shofetim (1 page each) Month 2: Shemuel Month 3: Melakhim Month 4: Yeshayahu Month 5: Yirmiyahu (2 pages) Month 6: Yehezkel Month 7: Trei Asar (2 pages) Month 8: Iyyov Month 9: Mishlei & Kohelet Month 10: Megillot (except Kohelet) & Daniel Months 11-12: Divrei HaYamim & Ezra-Nehemiah (3 pages) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (six-month cycle) Chart for Reading Sefer Tehillim (leap year) Guide to Reading the Five Megillot in the Synagogue Sources and Notes (English) A Guide to Reading Nevi’im and Ketuvim Introduction What purpose did the divisions serve? They let Moses pause to reflect between sections and between topics. The matter may be inferred: If a person who heard the Torah directly from the Holy One, Blessed be He, who spoke with the Holy Spirit, must pause to reflect between sections and between topics, then this is true all the more so for an ordinary person who hears it from another ordinary person. (On the parashiyot petuhot and setumot. From Dibbura de-Nedava at the beginning of Sifra.) A Basic Problem with Reading Tanakh Knowing where to stop to pause and reflect is not a trivial detail when it comes to reading Tanakh. In my own study, simply not knowing where to start reading and where to stop kept me, for many years, from picking up a Tanakh and reading the books I was unfamiliar with. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel

Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel Corinne Cath Thesis Bachelor Cultural Anthropology 2011 Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish Immigration to Israel Thesis Bachelor Cultural Anthropology 2011 Corinne Cath 3337316 C,[email protected] Supervisor: F. Jara-Gomez Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel This thesis is dedicated to my grandfather Kees Cath and my grandmother Corinne De Beaufort, whose resilience and wits are an inspiration always. Aliyah and the Ingathering of Exiles: Jewish immigration to Israel Table of Contents Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... 4 General Introduction ............................................................................................. 5 1.Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................... 8 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Anthropology and the Nation-State ........................................................................ 10 The Nation ........................................................................................................ 10 States and Nation-States ................................................................................... 11 Nationalism ......................................................................................................