A Human Capital Interpretation of Jewish Economic History∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60628-8 - The Origins of Judaism: From Canaan to the Rise of Islam Robert Goldenberg Excerpt More information A Note of Introduction this book tells the story of the emergence of judaism out of its biblical roots, a story that took well over a thousand years to run its course. When this book begins there is no “Judaism” and there is no “Jewish people.” By the end, the Jews and Judaism are everywhere in the Roman Empire and beyond, more or less adjusted to the rise of Christianity and ready to absorb the sudden appearance of yet another new religion called Islam. It may be useful to provide a few words of introduction about the name Judaism itself. This book will begin with the religious beliefs and practices of a set of ancient tribes that eventually combined to form a nation called the Children of Israel. Each tribe lived in a territory that was called by its tribal name: the land of Benjamin, the land of Judah, and so on. According to the biblical narrative, these tribes organized and maintained a unified kingdom for most of the tenth century BCE, but then the single tribe of Judah was separated from the others in a kingdom of its own, called the Kingdom of Judah (in Hebrew yehudah) to distinguish it from the larger Kingdom of Israel to its north. Thus the name Israel was essentially a national or ethnic designation, while the name Judah simultaneously meant a smaller ethnic entity, included within the larger one, and the land where that group dwelt for hundreds of years. -

Estimating the Effects of Fiscal Policy in OECD Countries

Estimating the e®ects of ¯scal policy in OECD countries Roberto Perotti¤ This version: November 2004 Abstract This paper studies the e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP, in°ation and interest rates in 5 OECD countries, using a structural Vector Autoregression approach. Its main results can be summarized as follows: 1) The e®ects of ¯scal policy on GDP tend to be small: government spending multipliers larger than 1 can be estimated only in the US in the pre-1980 period. 2) There is no evidence that tax cuts work faster or more e®ectively than spending increases. 3) The e®ects of government spending shocks and tax cuts on GDP and its components have become substantially weaker over time; in the post-1980 period these e®ects are mostly negative, particularly on private investment. 4) Only in the post-1980 period is there evidence of positive e®ects of government spending on long interest rates. In fact, when the real interest rate is held constant in the impulse responses, much of the decline in the response of GDP in the post-1980 period in the US and UK disappears. 5) Under plausible values of its price elasticity, government spending typically has small e®ects on in°ation. 6) Both the decline in the variance of the ¯scal shocks and the change in their transmission mechanism contribute to the decline in the variance of GDP after 1980. ¤IGIER - Universitµa Bocconi and Centre for Economic Policy Research. I thank Alberto Alesina, Olivier Blanchard, Fabio Canova, Zvi Eckstein, Jon Faust, Carlo Favero, Jordi Gal¶³, Daniel Gros, Bruce Hansen, Fumio Hayashi, Ilian Mihov, Chris Sims, Jim Stock and Mark Watson for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Jewish Occupational Selection: Education, Restrictions, Or Minorities?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Botticini, Maristella; Eckstein, Zvi Working Paper Jewish Occupational Selection : Education, Restrictions, or Minorities? IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1224 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Botticini, Maristella; Eckstein, Zvi (2004) : Jewish Occupational Selection : Education, Restrictions, or Minorities?, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 1224, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/20477 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Zeraim Tractates Terumot and Ma'serot

THE JERUSALEM TALMUD FIRST ORDER: ZERAIM TRACTATES TERUMOT AND MA'SEROT w DE G STUDIA JUDAICA FORSCHUNGEN ZUR WISSENSCHAFT DES JUDENTUMS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON E. L. EHRLICH BAND XXI WALTER DE GRUYTER · BERLIN · NEW YORK 2002 THE JERUSALEM TALMUD Ή^ίτ τΐίΛη FIRST ORDER: ZERAIM Π',ΙΓΙΪ Π0 TRACTATES TERUMOT AND MA'SEROT ΓτηελΡΏΐ niQnn rnooü EDITION, TRANSLATION, AND COMMENTARY BY HEINRICH W. GUGGENHEIMER WALTER DE GRUYTER · BERLIN · NEW YORK 2002 Die freie Verfügbarkeit der E-Book-Ausgabe dieser Publikation wurde ermöglicht durch den Fachinformationsdienst Jüdische Studien an der Universitätsbibliothek J. C. Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main und 18 wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken, die die Open-Access-Transformation in den Jüdischen Studien unterstützen. ISBN 978-3-11-017436-6 ISBN Paperback 978-3-11-068128-4 ISBN 978-3-11-067718-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-090846-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067726-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067730-0 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. For This work is licensed under the Creativedetails go Commons to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution 4.0 International Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Das E-Book ist als Open-Access-Publikation verfügbar über www.degruyter.com, Library of Congresshttps://www.doabooks.org Control Number: 2020942816und https://www.oapen.org 2020909307 Bibliographic informationLibrary published of Congress by the Control Deutsche Number: Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek DeutscheThe Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data detailedare available bibliographic on the data Internet are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Introduction

Introduction I Our knowledge and understanding of Judaism in antiquity is constantly chang- ing as each generation of scholars reads the ancient sources anew, and applies differing approaches to the interpretation of already familiar texts and sources. At the same time, the careful decipherment of the primary evidence, in the tra- dition of the historical philological school, remains crucial for any attempt to reconstruct the past. Yet, it is the discovery of new material sources, includ- ing new archaeological findings, and the benefit of improved readings of epi- graphic sources such as papyri, or early manuscripts of rabbinic texts, which stimulate new insights into Jewish history. The systematic analysis of the pri- mary sources, their collection, collation, and integration with previous data, must necessarily come before any effort to elucidate antiquity. Based on a solid platform of primary evidence, the balanced and judicious application of new approaches to reading ancient sources can impact greatly on the way we inter- pret the past. Modern research challenges traditional understandings of Jewish texts, recasts the histories of formative events and people, and questions fun- damental ideas and beliefs. This volume, reasserting the importance of this set of priorities offers new innovative studies, many of an interdisciplinary nature, in the broad field of ancient Judaism. It is dedicated to Tal Ilan as a tribute to her in recognition of the importance of her pioneering scholarship in ancient Judaism. II Tal Ilan was born on Kibbutz Lahav in the Negev desert on January 21st, 1956. She studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and in 1991, submitted her PhD thesis on the subject, Jewish Women in Palestine during the Hellenistic- Roman Period (332BCE–200CE). -

Professor Zvi Eckstein

Professor Zvi Eckstein January 2020 The Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya - IDC P. O. Box 167, Herzliya, ISRAEL 46150 [email protected] Phone: 972-9-960-2706 (office); 972-3-647-8146 (home) 972-5 0-381-0090 (mobile); Fax: 972-9-960-2758 (office) Home Page: http://www1.idc.ac.il/Faculty/Eckstein/index.html CURRICULUM VITAE Date of Birth: April 9, 1949, Israel Marital Status: Married + 3 children + 3 grandchildren EDUCATION 1971-1974 Tel-Aviv University Economics B.A. 1974 1976-1980 University of Minnesota Economics Ph.D.1981 Doctoral Dissertation: Rational Expectations Modeling of Agricultural Supply: The Egyptian Case Current Positions: Dean and Professor, the Tiomkin School of Economics, the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya – IDC. Head, the Aaron Economic Policy Institute, IDC, Herzliya Tel Aviv University, the Eitan Berglas School of Economics, Emeritus Professor. ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1980-1984 Yale University, Department of Economics & Economic Growth Center, Assistant Professor 1983-1985 Tel Aviv University, Department of Economics, Lecturer 1985-1989 Tel-Aviv University, Department of Economics Senior Lecturer 1989-1999 Tel-Aviv University, Department of Economics Associate Professor 1999-2012 Tel-Aviv University, Berglas School of Economics Full Professor 1986-1987 Carnegie-Mellon University, GSBA, Visiting Associate Professor 1987-1988 University of Pittsburgh, Department of Economics, Visiting Associate Professor 1989-2001 Boston University, Department of Economics Professor 2001-2006 University of Minnesota, Department of Economics Professor 2006-2011 Bank of Israel Deputy Governor 2011-2019 University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Business Visiting Professor ACADEMIC AND PROFESSIONAL AWARDS 1976-78 University of Minnesota, Korda Fellowship 1982 General Service Foundation, Grant to the Economic Growth Center at Yale University. -

Ims List Sanitation Compliance and Enforcement Ratings of Interstate Milk Shippers April 2017

IMS LIST SANITATION COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT RATINGS OF INTERSTATE MILK SHIPPERS APRIL 2017 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Rules For Inclusion In The IMS List Interstate milk shippers who have been certified by State Milk sanitation authorities as having attained the milk sanitation compliance ratings are indicated in the following list. These ratings are based on compliance with the requirements of the USPHS/FDA Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance and Grade A Condensed and Dry Milk Products and Condensed and Dry Whey and were made in accordance with the procedures set forth in Methods of Making Sanitation Rating of Milk Supplies. *Proposal 301 that was passed at 2001 NCIMS conference held May 5-10, 2001, in Wichita, Kansas and concurred with by FDA states: "Transfer Stations, Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants must achieve a sanitation compliance rating of 90 or better in order to be eligible for a listing in the IMS List. Sanitation compliance rating scores for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in the IMS List". Therefore, the publication of a sanitation compliance rating score for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in this edition of the IMS List. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL LISTS WHICH HAVE BEEN ISSUED HERETOFORE ALL PRECEDING LISTS AND SUPPLEMENTS THERETO ARE VOID. The rules for inclusion in the list were formulated by the official representatives of those State milk sanitation agencies who have participated in the meetings of the National Conference of Interstate Milk Shipments. -

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

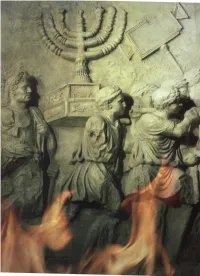

The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction in the Last Chapter, You Read About the Origins of Judaism

CHAPTER 4 Roman soldiers destroy theTemple of Jerusalem and carry off sacred treasures. The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you read about the origins of Judaism. In this chapter, you will discover how Judaism was preserved even after the Hebrews lost their homeland. As you have learned, the Hebrew kingdom split in two after the death of King Solomon. Weakened by this division, the Hebrews were less able to fight off invaders. The northern kingdom of Israel was the first to fall. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered Israel. The kingdom's leaders were carried off to Mesopotamia. In 597 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was invaded by another Meso- potamian power, Babylon. King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon laid siege to the city of Jerusalem. The Hebrews fought off the siege until their food ran out. With the people starving, the Babylonians broke through the walls and captured the city. In 586 B.C.E., Nebuchadrezzar burned down Solomon's great Temple of Jerusalem and all the houses in the city. Most of the people of Judah were taken as captives to Babylon. The captivity in Babylon was the begin- ning of the Jewish Diaspora. The word diaspora means "a scattering." Never again would most of the followers of Judaism be together in a single homeland. Yet the Jews, as they came to be known, were able to keep Judaism alive. In this chapter, you will first learn about four important Jewish beliefs. Then you will read about the Jews' struggle to preserve Judaism after they had been forced to settle in many lands.