Religions-11-00085-V2.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.5.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-60628-8 - The Origins of Judaism: From Canaan to the Rise of Islam Robert Goldenberg Excerpt More information A Note of Introduction this book tells the story of the emergence of judaism out of its biblical roots, a story that took well over a thousand years to run its course. When this book begins there is no “Judaism” and there is no “Jewish people.” By the end, the Jews and Judaism are everywhere in the Roman Empire and beyond, more or less adjusted to the rise of Christianity and ready to absorb the sudden appearance of yet another new religion called Islam. It may be useful to provide a few words of introduction about the name Judaism itself. This book will begin with the religious beliefs and practices of a set of ancient tribes that eventually combined to form a nation called the Children of Israel. Each tribe lived in a territory that was called by its tribal name: the land of Benjamin, the land of Judah, and so on. According to the biblical narrative, these tribes organized and maintained a unified kingdom for most of the tenth century BCE, but then the single tribe of Judah was separated from the others in a kingdom of its own, called the Kingdom of Judah (in Hebrew yehudah) to distinguish it from the larger Kingdom of Israel to its north. Thus the name Israel was essentially a national or ethnic designation, while the name Judah simultaneously meant a smaller ethnic entity, included within the larger one, and the land where that group dwelt for hundreds of years. -

The Proximity of the Pre-Samaritan Qumran Scrolls to the Sp*

chapter 27 The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Proximity of the Pre-Samaritan Qumran Scrolls to the sp* The study of the Samaritans and the scrolls converge at several points, definitely with regard to the biblical scrolls, but also regarding several nonbiblical scrolls. Recognizing the similarities between the sp and several Qumran biblical scrolls, some scholars suggested that these scrolls, found at Qumran, were actu- ally Samaritan. This assumption implies that these scrolls were copied within the Samaritan community, and somehow found their way to Qumran. If cor- rect, this view would have major implications for historical studies, and for the understanding of the Qumran and Samaritan communities. This view could imply that Samaritans lived or visited at Qumran, or that the Qumran commu- nity received Samaritan documents, but other scenarios are possible as well. A rather extreme suggestion, proposed by Thord and Maria Thordson, would be that the inhabitants of Qumran were not Jewish, but Samaritan Essenes who fled to Qumran after the destruction of the Samaritan Temple by John Hyrcanus in 128 bce.1 Although this view is not espoused by many scholars, it needs to be taken seriously. The major proponent of the theory that Samaritan scrolls were found at Qumran was M. Baillet in a detailed study of the readings of the sp agreeing with the Qumran texts known until 1971.2 Baillet provided no specific arguments for this view other than the assumption of a close rela- tion between the Essenes and the Samaritans suggested by J. Bowman3 and * I devote this paper to the two areas that were in the center of Alan Crown’s scholarly interests, the Samaritans and the Scrolls, in that sequence. -

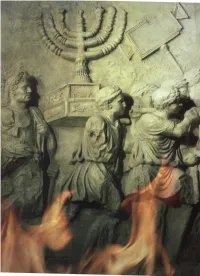

The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction in the Last Chapter, You Read About the Origins of Judaism

CHAPTER 4 Roman soldiers destroy theTemple of Jerusalem and carry off sacred treasures. The Struggle to Preserve Judaism 12.1 Introduction In the last chapter, you read about the origins of Judaism. In this chapter, you will discover how Judaism was preserved even after the Hebrews lost their homeland. As you have learned, the Hebrew kingdom split in two after the death of King Solomon. Weakened by this division, the Hebrews were less able to fight off invaders. The northern kingdom of Israel was the first to fall. In 722 B.C.E., the Assyrians conquered Israel. The kingdom's leaders were carried off to Mesopotamia. In 597 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judah was invaded by another Meso- potamian power, Babylon. King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon laid siege to the city of Jerusalem. The Hebrews fought off the siege until their food ran out. With the people starving, the Babylonians broke through the walls and captured the city. In 586 B.C.E., Nebuchadrezzar burned down Solomon's great Temple of Jerusalem and all the houses in the city. Most of the people of Judah were taken as captives to Babylon. The captivity in Babylon was the begin- ning of the Jewish Diaspora. The word diaspora means "a scattering." Never again would most of the followers of Judaism be together in a single homeland. Yet the Jews, as they came to be known, were able to keep Judaism alive. In this chapter, you will first learn about four important Jewish beliefs. Then you will read about the Jews' struggle to preserve Judaism after they had been forced to settle in many lands. -

|||GET||| the Pentateuch 1St Edition

THE PENTATEUCH 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Gene M Tucker | 9780687008421 | | | | | Old Testament Inasmuch as I've read, the theology is as sound as the insight into some of the most difficult material in the Bible. Ester Esther [d]. Others stressed the Son of Mana distinctly other-worldly figure who would appear as a judge at the end of time ; and some harmonised the two by expecting a this-worldly messianic kingdom which would last for a set period and be followed by the other-worldly age or World to Come. The theological process The Pentateuch 1st edition which the term Law and the common authorship and authority of Moses was attached to the whole corpus of the Pentateuch is known as canonization. Judith [g]. The first edition sold over sixty thousand copies. Translated by Andrew R. The Old Testament often abbreviated OT is the first part of the Christian biblical canonwhich is based primarily upon the twenty-four books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakha collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites believed by most Christians and religious Jews The Pentateuch 1st edition be the sacred Word of God. The proposal will be made in dialogue with the other literary methods set out in the previous chapters, but space limitations will mean that I will need to rely on more detailed argument in other publications. Victor P. Category Description for Journey Through the Bible :. Baruch is not in the Protestant Bible or the Tanakh. Textbook lessons coordinate with the reading passages rather than the workbook lessons which means there might be more than one workbook lesson per textbook lesson. -

The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Scribal Culture of Second Temple Judaism

The Samaritan Pentateuch and the Scribal Culture of Second Temple Judaism Abstract: The Samaritan Pentateuch (SP), along with its Qumran forebears, has deservedly been regarded as a key source of information for understanding the scribal culture of early Judaism. Yet studies have tended to emphasize the relative uniformity of the characteristic pre-SP readings as evidence of a scribal approach distinct within Second Temple Judaism. This article argues that both the uniformity and the distinctiveness of these readings have been overstated: there is more internal diversity within pre-SP than is usually recognized, and similar or identical readings are also preserved in other manuscript traditions. Rather than representing a distinctive scribal approach or school, the readings of pre-SP are better taken as a particularly concentrated example of scribal attitudes and techniques that appear to have been widespread in early Judaism. Keywords: Samaritan Pentateuch, Pre-Samaritan Texts, Second Temple Judaism, Scribes, Scribal Culture, Harmonization, Qumran Biblical Manuscripts, Hellenistic Culture, 4QpaleoExodm, 4QNumb Scholars seeking to understand the ways texts were composed and transmitted in ancient Judaism often struggle with how to connect textual evidence with historical and cultural realities.1 In earlier stages of scholarship, such issues were not usually regarded as especially important. Analysis of biblical manuscripts and versions focused primarily on recovery of the “original text”; in this sense, materials introduced by scribes in the course of transmission were treated as significant only insofar as, once identified, these materials could be bracketed out, and something closer to the Urtext could be reconstructed.2 More recently, much more attention has been paid to such scribal interventions as cultural products in their own right; as windows not just on the development of the text but on the attitudes and ideologies of the individuals and groups that comprised the diverse phenomena we collectively label Second Temple Judaism. -

The Length of Israel's Sojou Rn in Egypt

THE LENGTH OF ISRAEL'S SOJOU RN IN EGYPT JACK R. RIGGS Associate Professor of Bible Cedarville College The chronological framework of Biblical events from the time of Abraham to David rests upon two pivotal texts of Scripture. The first is I Kings 6:1, which dates the Exodus from Egypt 480 years before the fourth year of Solomon. The second pivotal date for the Biblical chronology of this period is Exodus 12 :40 which dates the arrival of Jacob's family in Egypt years before the Exodus. The purpose of this paper will be to discuss the problem of the length of Israel's sojourn in Egypt. This problem is important, as already suggested, because it has to do with dating events in the cen turies prior to the Exodus. There are at least three possible solutions to the problem of the length of Israel's Egyptian sojourn. The first view is that the time span of the sojourn was only 215 years. A second solution is the view of 400 years for the sojourn. The third, and final, solution to be discussed is the idea that 430 years elapsed between the entrance of Jacob and his family into Egypt and their Exodus under Moses' leadership. The View That The Egyptian Sojourn Was 215 Years The most commonly held view of the length of Israel's sojourn in Egypt is the 215 year idea. To state the view simply, the chrono logical notations of Genesis 15:13, This article was presented as a paper at the Midwestern Section meet ing of the Evangelical Theological Society on April 17, 1970, at Grace Theological Seminary. -

Name: Date: H.W.#: ___My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and The

Name: _____________________________ Date: __________________ H.W.#: ______ My World History Chapter 5 – “Judaism and the Jewish People” Section 1 – The Origins of Judaism ! Terms to understand when reading: 1. Jews – a group of people who share the same religious and cultural beliefs in God and worship following an ancient text known as the Torah. In ancient days, Jews were also known as the Hebrews and Israelites. Many Hebrews traveled from Canaan to Egypt to escape poverty, only to be enslaved by the Pharaohs. One of their leaders named Moses helped to free them from captivity in Egypt and led them back into Canaan (see the map) to an area that was to become known as the Jewish Promised Land. This land would later be called Judah, and much later known as Israel. In modern times, the ancient land of Canaan is now divided between Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Palestine. 2. monotheism - belief in one God. Jews, along with several other religions, believe that there is only one divine spirit who can be worshiped. In ancient times, the Hebrew God was sometimes referred to as Jehovah or Yahweh. Judaism, as a faith, is one of the world’s oldest religions and it said to date back at least 3000 years. (Some theologians place the religion’s date of origin closer to 4000 years.) 3. ethics - Simply put, ethics help to guide individuals from understanding right from wrong. The teaching of ethical principals is the foundation for most religions, including Judaism. In Judaism, as well as Christianity, the ethics of the religion and culture are clearly mapped out in the commandments. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

An Examination of the Supposed Pre-Samaritan Texts from Qumran Chelica L

An Examination of the Supposed pre-Samaritan Texts from Qumran Chelica L. Hiltunen September 2007 Abstract A debate continues among Dead Sea Scrolls scholars as to how best classify the manuscript finds from the eleven caves which boarder the Dead Sea. Emanuel Tov argues that the biblical scrolls are best organized by their textual character, that is, according to their filiation to the three later versions: the Masoretic Text (MT), the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP), the proposed Hebrew Vorlage behind the Septuagint (LXX), or, in cases of inconsistent agreement with the versions, identifying the manuscripts as non-aligned. Though this approach to categorizing manuscripts is helpful, the standards for determining a manuscript’s affiliation with the later versions are vague. As a result, the textual character of many scrolls is in contention, especially in regard to their relationship to the Samaritan Pentateuch. This study contends that there are different categories of variants that impact the designation of a manuscript’s textual character. Secondary variants, or lack there of, are the most important element for determining a scroll’s relationship, if any, to the three later versions (MT, SP, LXX). Secondary variants (also termed secondary readings) are defined as alterations found in the text due to scribal intervention, both intentional and accidental. Agreement or disagreement between secondary variants present in the scrolls and the later version is the most importing criterion for determining manuscript filiation. This investigation focuses on manuscripts of the Pentateuch that Tov has classified as relating to the both SP and MT, SP and LXX, and SP and the non-aligned category. -

Scripturalization and the Aaronide Dynasties

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures Volume 13, Article 6 DOI:10.5508/jhs.2013.v13.a6 Scripturalization and the Aaronide Dynasties JAMES W. WATTS Articles in JHS are being indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, RAMBI, and BiBIL. Their abstracts appear in Religious and Theological Abstracts. The journal is archived by Library and Archives Canada and is accessible for consultation and research at the Electronic Collection site maintained by Library and Archives Canada. ISSN 1203–1542 http://www.jhsonline.org and http://purl.org/jhs SCRIPTURALIZATION AND THE AARONIDE DYNASTIES JAMES W. WATTS SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY Evidence for the history of the Second Temple priesthood is very fragmentary and incomplete. To the best of our knowledge, how- ever, worship at the temple site in Jerusalem was controlled from ca. 535 to 172 B.C.E. by a single family, the descendants of Jeshua ben Jehozadak, the first post-exilic high priest (the family is often called the Oniads). After disruptions caused by civil wars and the Maccabean Revolt, they were replaced by another family, the Hasmoneans, who controlled the high priesthood from at least 152 until 37 B.C.E. Sources from the Second Temple period indicate that both families claimed descent from Israel’s first high priest, Aaron.1 1 For the Oniads’ genealogical claims, see 1 Chr 6:3–15; Ezra 2:36; 3:2. For the Hasmoneans’ claims, see 1 Macc 2:1; cf. 1 Chr 24:7. No ancient source challenges these claims, but many modern historians have been skeptical of them (e.g., J. Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Israel [trans. -

Download Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament

Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament JESOT is published bi-annually online at www.jesot.org and in print by Wipf and Stock Publishers. 199 West 8th Avenue, Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401, USA ISBN 978-1-7252-6256-0 © 2020 by Wipf and Stock Publishers JESOT is an international, peer-reviewed journal devoted to the academic and evangelical study of the Old Testament. The journal seeks to publish current academic research in the areas of ancient Near Eastern backgrounds, Dead Sea Scrolls, Rabbinics, Linguistics, Septuagint, Research Methodology, Literary Analysis, Exegesis, Text Criticism, and Theology as they pertain only to the Old Testament. The journal seeks to provide a venue for high-level scholarship on the Old Testament from an evangelical standpoint. The journal is not affiliated with any particular academic institution, and with an international editorial board, online format, and multi-language submissions, JESOT seeks to cultivate Old Testament scholarship in the evangelical global community. JESOT is indexed in Old Testament Abstracts, Christian Periodical Index, The Ancient World Online (AWOL), and EBSCO databases Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament Executive Editor Journal correspondence and manuscript STEPHEN J. ANDREWS submissions should be directed to (Midwestern Baptist Theological [email protected]. Instructions for Seminary, USA) authors can be found at https://wipfandstock. com/catalog/journal/view/id/7/. Editor Books for review and review correspondence RUSSELL L. MEEK (Ohio Theological Institute, USA) should be directed to Andrew King at [email protected]. Book Review Editor All ordering and subscription inquiries ANDREW M. KING should be sent to [email protected]. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

JUDAISM A Supplemental Resource for GRADE 12 World of Religions A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE JUDAISM A Supplemental Resource for GRADE 12 World of Religions A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE 2019 Manitoba Education Manitoba Education Cataloguing in Publication Data Judaism : Grade 12 world of religions : a Canadian perspective Includes bibliographical references. This resource is available in print and electronic formats. ISBN: 978-0-7711-7933-4 (pdf) ISBN: 978-0-7711-7935-8 (print) 1. Judaism—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 2. Religion—Study and teaching (Secondary)—Manitoba. 3. Multiculturalism—Study and teaching (Secondary) --Manitoba. 4. Spirituality – Study and teaching (Secondary) – Manitoba. 5. Religion and culture – Study and teaching (Secondary) -- Manitoba. I. Manitoba. Manitoba Education. 379.28 Copyright © 2019, the Government of Manitoba, represented by the Minister of Education. Manitoba Education Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Every effort has been made to acknowledge original sources and to comply with copyright law. If cases are identified where this has not been done, please notify Manitoba Education. Errors or omissions will be corrected in a future edition. Sincere thanks to the authors, artists, and publishers who allowed their original material to be used. All images found in this resource are copyright protected and should not be extracted, accessed, or reproduced for any purpose other than for their intended educational use in this resource. Any websites referenced in this resource are subject to change without notice. Educators are advised to preview and evaluate websites and online resources before recommending them for student use. Print copies of this resource (stock number 80750) can be purchased from the Manitoba Learning Resource Centre.