Download Journal for the Evangelical Study of the Old Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Law of Christ? Peter Ditzel

What Is the Law of Christ? Peter Ditzel "Bear one another's burdens, and so fulfill the law of Christ" (Galatians 6:2). Although it is alluded to in other Scriptures, this is the only place in all the Bible that uses the phrase "law of Christ." What is the law of Christ? As Christians, we should have more than vague ideas about something so connected to Jesus Christ as His law. Is the law of Christ a set of commandments like the Ten Commandments? Is it one command, love, that can be expressed in slightly more detail as "bear one another's burdens"? Is it the law that Jeremiah prophesied God would put in our inward parts and write on our hearts? (Jeremiah 31:33). Let's find out. A Command If there is a law of Christ, we should expect something in the way of commands, or, at least, a command. In John 13:34, Jesus says, "A new commandment I give to you, that you love one another, just like I have loved you; that you also love one another." But what about all of the other commands about loving our neighbor, loving our enemies, and the many things Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount and elsewhere? I believe that just as Paul, after quoting some of the Ten Commandments, said, "whatever other commandments there are, are all summed up in this saying, namely, 'You shall love your neighbour as yourself'" (Romans 13:9), so also all of Jesus' commands about how we are to live can be summed into His one command, "love one another." What about, "You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind"? (Matthew 22:37). -

LAW of CHRIST - NEW COVENANT by Donna Dorsey Wulfemeyer Updated 2020

LAW OF CHRIST - NEW COVENANT By Donna Dorsey Wulfemeyer Updated 2020 The Law of Christ states that we can’t be good enough or righteous enough to enter heaven by following the Law and The Prophets. It says we need to believe in Jesus as our Messiah (savior). His death for us is what makes us righteous in God’s sight. For our salvation, which can never be earned, God simply asks us to love him, love others (both believers and non-believers) and believe in God’s son. The NT contains hundreds of commands. All of them come under the general heading of love. Everything He commands is an expression of love. This I believe is the Law of Christ and this fulfills all that was said in the Law and the prophets without the need to look at a check list of demands. Jesus asked believers to love each other in order to show the world we are his followers because in doing so we follow his example for living. Receiving our righteousness from God thru Jesus, not the law, explains the Law of Christ which is the New Covenant. Prior to Christ the law was a list of do’s and don’ts that were created to help people live peaceably with God and others. However people were unable to keep the commandments so the blood of animals was shed on our behalf. After Jesus was the final sacrifice, the Law of Christ took effect; by belief in Christ all our sins are covered/removed and we are made righteous in God sight. -

Wind Chasers Beware- Ecclesiastes 1

Wind Chasers Beware Eccleiase 1 Wisdom Literature While other civilizations shared in wisdom literature, the major difference is the Hebrew wisdom writings acknowledged one God, denying materialism and [the worship of many gods.] 2 Types of Wisdom Literature: Didactic (Practical/ Teaching) and Philosophical/Pessimistic (Critical/ Reflective/Questioning). The goal of wisdom is a proper relationship with YAHWEH. Wisdom Focus Didactic wisdom literature advocates the development of prudential habits, skills, and virtues. The aim is to develop moral character, personal success and happiness, safety, and well-being. Proverbs is an example of this type. Philosophical/Pessimistic wisdom literature delves deeper into issues facing mankind. It portrays the emptiness and folly of the search for insight and understanding apart from God. Job and Ecclesiastes are examples of this type. The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem. Ecclesiastes 1:1 Consider the Source Advice is only as good as the one giving it. Only 2 ways of learning something: Personal experience or 2nd hand. Solomon was the wisest man that ever lived. (See 1 Kings 3:11-14) Solomon saw one of Israel's wealthier periods. Ecclesiastes 1:2-6 “ Vanity of vanities,” says the Preacher, “Vanity of vanities! All is vanity.” What advantage does man have in all his work which he does under the sun? A generation goes and a generation comes, but the earth remains forever. Also, the sun rises and the sun sets; and hastening to its place it rises there again. Blowing toward the south, then turning toward the north, the wind continues swirling along; and on its circular courses the wind returns. -

Is Emptiness Apart From

ALL IS EMPTINESS APART FROM GOD (ECCLESIASTES 1 - 12) MEMORY VERSE: "Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: fear God and keep His commandments, for this is man's all.” ECCLESIASTES 12:13 TRUE OR FALSE: 1. “The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.” ECCLESIASTES 1:1 TRUE OR FALSE 2. “Vanity of vanities," says the Preacher; "Vanity of vanities, nothing is vanity." ECCLESIASTES 1:2 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 3. “That which has been is what (WILL, WON’T) be, that which is done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the (LIGHT, SUN)." ECCLESIASTES 1:9 4. "To everything there is a season, a (THEME, TIME) for every purpose under heaven:" ECCLESIASTES 3:1 5. " He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also He has put eternity in their (HATS, HEARTS) ...” ECCLESIASTES 3:11 TRUE OR FALSE: 6. “I know that whatever God does, it shall be forever. Nothing can be added to it, and nothing taken from it. God does it, that men should fear before Him.” ECCLESIASTES 3:14 TRUE OR FALSE 7. One is better than two, because one has a good reward for his labor. ECCLESIASTES 4:9 TRUE OR FALSE CIRCLE THE CORRECT WORDS: 8. " Do not be (RASH, REAL) with your mouth, and let not your heart utter anything hastily before God. For God is in heaven, and you on earth; therefore let your (WORKS, WORDS) be few." ECCLESIASTES 5:2 9. " As for every man to whom God has given riches and wealth, and given him power to eat of it, to receive his heritage and (REJOICE, REST) in his labor-this is the gift of God." ECCLESIASTES 5:19 10. -

Appendix 1A — Books of the Bible

Appendix 1a — Books of the Bible Old Testament Books Pentateuch Wisdom Books The Book of Genesis The Book of Job The Book of Exodus The Book of Psalms The Book of Leviticus The Book of Proverbs The Book of Numbers The Book of Ecclesiastes The Book of Deuteronomy The Song of Songs The Book of Wisdom The Book of Sirach (Ecclesiasticus) Historical Books Prophetic Books The Book of Joshua The Book of Isaiah The Book of Judges The Book of Jeremiah The Book of Ruth The Book of Lamentations The First Book of Samuel The Book of Baruch The Second Book of Samuel The Book of Ezekiel The First Book of Kings The Book of Daniel The Second Book of Kings The Book of Hosea The First Book of Chronicles The Book of Joel The Second Book of Chronicles The Book of Amos The Book of Ezra The Book of Obadiah The Book of Nehemiah The Book of Jonah The Book of Tobit The Book of Micah The Book of Judith The Book of Nahum The Book of Esther The Book of Habakkuk The First Book of Maccabees The Book of Zephaniah The Second Book of Maccabees The Book of Haggai The Book of Zechariah The Book of Malachi New Testament Books Gospels Epistles The Gospel according to Matthew The Letter to the Romans The Gospel according to Mark The First Letter to the Corinthians The Gospel according to Luke The Second Letter to the Corinthians The Gospel according to John The Letter to the Galatians The Letter to the Ephesians The Letter to the Philippians Acts (beginning of the Christian Church) The Letter to the Colossians The Acts of the Apostles The First Letter to the Thessalonians The Second Letter to the Thessalonians The First Letter to Timothy The Second Letter To Timothy The Letter to Titus The Letter to Philemon The Letter to the Hebrews The Catholic Letters The Letter of James The First Letter of Peter The Second Letter of Peter The First Letter of John The Second Letter of John The Third Letter of John The Letter of Jude Revelation The Book of Revelation . -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

Book of Nahum

Book of Nahum Title: The book’s title is taken from the prophet-of-God’s oracle against Nineveh, the capital of Assyria. Nahum means “comfort” or “consolation”, and is a short form of Nehemiah (“comfort of Yahweh”). Nahum is not quoted in the New Testament, although there may be an allusion to (Nahum 1:15 in Romans 10:15; Isaiah 52:7). Author – Date: The author of the prophecy is named simply “Nahum the Elkoshite” (1:1), and all that is known of the prophet is gleaned from this prophecy. Probably the identity of the prophet is obscured so his message can be prominent. Nahum’s mission was to comfort the kingdom of Judah, following the destruction of Israel by Assyria, by announcing God’s coming judgment on Nineveh, the capital of Assyria. The purpose of Nahum’s prophecy is twofold: (1) To deliver a message of judgment and destruction against Nineveh; and (2) To give comfort to Judah, so recently ravaged by Assyria. Since Assyria is doomed, it will constitute a threat no longer. With no mention of any kings in the introduction, the date of Nahum’s prophecy must be implied by historical data. The message of judgment against Nineveh portrays a nation of strength, intimating a time not only prior to her fall (in 612 B.C.), but probably before the death of Ashurbanipal (in 626 B.C.), after which Assyria’s power fell rapidly. Being occupied with the doom on Nineveh, Nahum does not date his prophecy according to any of the kings of Israel or Judah. -

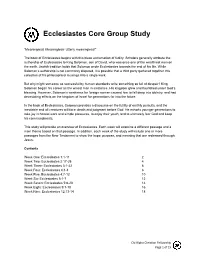

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study

Ecclesiastes Core Group Study “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless!” The book of Ecclesiastes begins with this bleak exclamation of futility. Scholars generally attribute the authorship of Ecclesiastes to King Solomon, son of David, who was once one of the wealthiest men on the earth. Jewish tradition holds that Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes towards the end of his life. While Solomon’s authorship is not commonly disputed, it is possible that a third party gathered together this collection of his philosophical musings into a single work. But why might someone so successful by human standards write something so full of despair? King Solomon began his career as the wisest man in existence. His kingdom grew and flourished under God’s blessing. However, Solomon’s weakness for foreign women caused him to fall deep into idolatry, and had devastating effects on the kingdom of Israel for generations far into the future. In the book of Ecclesiastes, Solomon provides a discourse on the futility of earthly pursuits, and the inevitable end all creatures will face: death and judgment before God. He exhorts younger generations to take joy in honest work and simple pleasures, to enjoy their youth, and to ultimately fear God and keep his commandments. This study will provide an overview of Ecclesiastes. Each week will examine a different passage and a main theme based on that passage. In addition, each week of the study will include one or more passages from the New Testament to show the hope, purpose, and meaning that are redeemed through Jesus. Contents Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 2 Week Two: Ecclesiastes 2:17-26 4 Week Three: Ecclesiastes 3:1-22 6 Week Four: Ecclesiastes 4:1-3 8 Week Five: Ecclesiastes 4:7-12 10 Week Six: Ecclesiastes 5:1-7 12 Week Seven: Ecclesiastes 5:8-20 14 Week Eight: Ecclesiastes 9:1-10 16 Week Nine: Ecclesiastes 12:13-14 18 Chi Alpha Christian Fellowship Page 1 of 19 Week One: Ecclesiastes 1:1-11 Worship Idea: Open in prayer, then sing some worship songs Opening Questions: 1. -

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun”

Ecclesiastes “Life Under the Sun” I. Introduction to Ecclesiastes A. Ecclesiastes is the 21st book of the Old Testament. It contains 12 chapters, 222 verses, and 5,584 words. B. Ecclesiastes gets its title from the opening verse where the author calls himself ‘the Preacher”. 1. The Septuagint (the translation of the Hebrew into the common language of the day, Greek) translated this word, Preacher, as Ecclesiastes and thus e titled the book. a. Ecclesiastes means Preacher; the Hebrew word “Koheleth” carries the menaing of preacher, teacher, or debater. b. The idea is that the message of Ecclesiastes is to be heralded throughout the world today. C. Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon. 1. Jewish tradition states Solomon wrote three books of the Bible: a. Song of Solomon, in his youth b. Proverbs, in his middle age years c. Ecclesiastes, when he was old 2. Solomon’s authorship had been accepted as authentic, until, in the past few hundred years, the “higher critics” have attempted to place the book much later and attribute it to someone pretending to be Solomon. a. Their reasoning has to do with a few words they believe to be of a much later usage than Solomon’s time. b. The internal evidence, however, strongly supports Solomon as the author. i. Ecc. 1:1 He calls himself the son of David and King of Jerusalem ii. Ecc. 1:12 Claims to be King over Israel in Jerusalem” iii. Only Solomon ruled over all Israel from Jerusalem; after his reign, civil war split the nation. Those in Jerusalem ruled over Judah. -

The Book of Nahum Author(S): Paul Haupt Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

The Book of Nahum Author(s): Paul Haupt Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1907), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259023 Accessed: 12/03/2010 14:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=sbl. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXVI Part I 1907 The Book of Nahum * PAUL HAUPT, LL.D. -

Ecclesiastes 1

International King James Version Old Testament 1 Ecclesiastes 1 ECCLESIASTES Chapter 1 before us. All is Vanity 11 There is kno remembrance of 1 ¶ The words of the Teacher, the former things, neither will there be son of David, aking in Jerusalem. any remembrance of things that are 2 bVanity of vanities, says the Teacher, to come with those that will come vanity of vanities. cAll is vanity. after. 3 dWhat profit does a man have in all his work that he does under the Wisdom is Vanity sun? 12 ¶ I the Teacher was king over Is- 4 One generation passes away and rael in Jerusalem. another generation comes, but ethe 13 And I gave my heart to seek and earth abides forever. lsearch out by wisdom concerning all 5 fThe sun also rises and the sun goes things that are done under heaven. down, and hastens to its place where This mburdensome task God has it rose. given to the sons of men by which to 6 gThe wind goes toward the south be busy. and turns around to the north. It 14 I have seen all the works that are whirls around continually, and the done under the sun. And behold, all wind returns again according to its is vanity and vexation of spirit. circuits. 15 nThat which is crooked cannot 7 hAll the rivers run into the sea, yet be made straight. And that which is the sea is not full. To the place from lacking cannot be counted. where the rivers come, there they re- 16 ¶ I communed with my own heart, turn again. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews.