Making the Soviet Intelligentsia: Universities and Intellectual Life Under Stalin and Khrushchev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Report 2019-2020

Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Nanoscience and Nanotechnology for Center University Aviv Tel Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology SCIENTIFIC REPORT 2019-2020 Scienti fic Report 2019–2020 Scienti Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology Powering Innovation Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology SCIENTIFIC REPORT October 2020 Tel Aviv University Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology Powering Innovation The cover image: A highly porous vaterite microspherulite filled with 3-nm gold seeds using the innovative freezing-induced loading technique. The image was taken by Dr. Gal Radovski of the TAU Center for Nanoscience & Nanotechnology and belongs to Prof. Pavel Ginzburg’s group. Graphic Design: Michal Semo Kovetz, TAU Graphic Design Studio Contents Part 1: Main activities and facilities ........................................................................................................................................7 Overview ................................................................................................................................................................................................................8 Hubs of innovation ...........................................................................................................................................................................................9 The Chaoul -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

State Composers and the Red Courtiers: Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930S

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Villa Ranan Blomstedtin salissa marraskuun 24. päivänä 2007 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Jyväskylä, in the Building Villa Rana, Blomstedt Hall, on November 24, 2007 at 12 o'clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 78 Simo Mikkonen State Composers and the Red Courtiers Music, Ideology, and Politics in the Soviet 1930s UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2007 Editors Seppo Zetterberg Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Irene Ylönen, Marja-Leena Tynkkynen Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Matti Rahkonen, Department of Languages, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, University of Jyväskylä Minna-Riitta Luukka, Centre for Applied Language Studies, University of Jyväskylä Raimo Salokangas, Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä URN:ISBN:9789513930158 ISBN 978-951-39-3015-8 (PDF) ISBN 978-951-39-2990-9 (nid.) ISSN 1459-4331 Copyright ©2007 , by University of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä University Printing House, Jyväskylä 2007 ABSTRACT Mikkonen, Simo State composers and the red courtiers. -

Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(S): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol

The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Author(s): Christopher Ely Source: Slavic Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, Tourism and Travel in Russia and the Soviet Union, (Winter, 2003), pp. 666-682 Published by: The American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3185650 Accessed: 06/06/2008 13:39 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aaass. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org The Origins of Russian Scenery: Volga River Tourism and Russian Landscape Aesthetics Christopher Ely BoJira onrcaHo, nepeonicaHo, 4 Bce-TaKHHe AgoicaHo. -

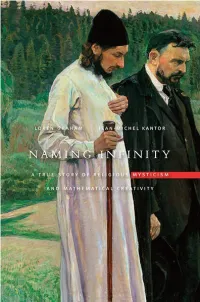

Naming Infinity: a True Story of Religious Mysticism And

Naming Infinity Naming Infinity A True Story of Religious Mysticism and Mathematical Creativity Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Graham, Loren R. Naming infinity : a true story of religious mysticism and mathematical creativity / Loren Graham and Jean-Michel Kantor. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-03293-4 (alk. paper) 1. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Religious aspects. 2. Mysticism—Russia (Federation) 3. Mathematics—Russia (Federation)—Philosophy. 4. Mathematics—France—Religious aspects. 5. Mathematics—France—Philosophy. 6. Set theory. I. Kantor, Jean-Michel. II. Title. QA27.R8G73 2009 510.947′0904—dc22â 2008041334 CONTENTS Introduction 1 1. Storming a Monastery 7 2. A Crisis in Mathematics 19 3. The French Trio: Borel, Lebesgue, Baire 33 4. The Russian Trio: Egorov, Luzin, Florensky 66 5. Russian Mathematics and Mysticism 91 6. The Legendary Lusitania 101 7. Fates of the Russian Trio 125 8. Lusitania and After 162 9. The Human in Mathematics, Then and Now 188 Appendix: Luzin’s Personal Archives 205 Notes 212 Acknowledgments 228 Index 231 ILLUSTRATIONS Framed photos of Dmitri Egorov and Pavel Florensky. Photographed by Loren Graham in the basement of the Church of St. Tatiana the Martyr, 2004. 4 Monastery of St. Pantaleimon, Mt. Athos, Greece. 8 Larger and larger circles with segment approaching straight line, as suggested by Nicholas of Cusa. 25 Cantor ternary set. -

Bajo El Signo Del Escorpión

Por Juri Lina Bajo el Signo del Escorpión pg. 1 de 360 - 27 de septiembre de 2008 Por Juri Lina pg. 2 de 360 - 27 de septiembre de 2008 Por Juri Lina PRESENTACION Juri Lina's Book "Under the Sign of the Scorpion" is a tremendously important book, self-published in the English language in Sweden by the courageous author. Jüri Lina, has been banned through out the U.S.A. and Canada. Publishers and bookstores alike are so frightened by the subject matter they shrink away and hide. But now, braving government disapproval and persecution by groups that do not want the documented information in Under the Sign of the Scorpion to see the light of day, Texe Marrs and Power of Prophecy are pleased to offer Mr. Lina's outstanding book. Lina's book reveals what the secret societies and the authorities are desperate to keep hidden—how Jewish Illuminati revolutionaries in the United States, Britain, and Germany—including Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin—conspired to overthrow the Czar of Russia. It details also how these monsters succeeded in bringing the bloody reign of Illuministic Communism to the Soviet Empire and to half the world's population. Under the Sign of the Scorpion reveals the whole, sinister, previously untold story of how a tiny band of Masonic Jewish thugs inspired by Satan, funded by Illuminati bigwigs, and emboldened by their Talmudic hatred were able to starve, bludgeon, imprison and massacre over 30 million human victims with millions more suffering in Soviet Gulag concentration camps. Fuhrer Adolf Hitler got his idea for Nazi concentration camps from these same Bolshevik Communist butchers. -

Boris Godunov

6 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 6 2008 Fondazione Stagione 2008 Teatro La Fenice di Venezia Lirica e Balletto Modest Musorgskij Boris odunov g odunov oris oris b G usorgskij m odest odest M FONDAZIONE TEATRO LA FENICE DI VENEZIA ALBO DEI FONDATORI Stato Italiano SOCI SOSTENITORI SOCI BENEMERITI CONSIGLIO DI AMMINISTRAZIONE Massimo Cacciari presidente Luigino Rossi vicepresidente Fabio Cerchiai Achille Rosario Grasso Giorgio Orsoni Luciano Pomoni Giampaolo Vianello Gigliola Zecchi Balsamo Davide Zoggia William P. Weidner consiglieri sovrintendente Giampaolo Vianello direttore artistico Fortunato Ortombina direttore musicale Eliahu Inbal COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI DEI CONTI Giancarlo Giordano, presidente Giampietro Brunello Adriano Olivetti Andreina Zelli, supplente SOCIETÀ DI REVISIONE PricewaterhouseCoopers S.p.A. ALBO DEI FONDATORI SOCI ORDINARI boris godunov opera in quattro atti e un prologo versione originale 1872 libretto e musica di Modest Musorgskij Teatro La Fenice domenica 14 settembre 2008 ore 19.00 turni A1-A2 martedì 16 settembre 2008 ore 19.00 turni D1-D2 giovedì 18 settembre 2008 ore 19.00 turni E1-E2 sabato 20 settembre 2008 ore 15.30 turni B1-B2 martedì 23 settembre 2008 ore 17.00 turni C1-C2 La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 6 Musorgskij in un ritratto fotografico di Repin. La Fenice prima dell’Opera 2008 6 Sommario 5 La locandina 7 Dimenticare Rimskij! di Michele Girardi 11 Anselm Gerhard «Roba da bambini» o «vera vocazione dell’artista»? La drammaturgia del Boris Godunov di Musorgskij tra opera tradizionale e teatro radicale -

Queuetopia: Second-World Modernity and the Soviet

QUEUETOPIA: SECOND-WORLD MODERNITY AND THE SOVIET CULTURE OF ALLOCATION by Andrew H. Chapman Bachelor of Arts, University of Rochester, 2004 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Andrew H. Chapman It was defended on March 22, 2013 and approved by David J. Birnbaum, Professor and Department Chair, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Nancy Condee, Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures Randall Halle, Klaus W. Jonas Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of German Nancy Ries, Associate Professor, Colgate University, Department of Anthropology and Peace & Conflict Studies Dissertation Advisor: Vladimir Padunov, Associate Professor, University of Pittsburgh, Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures ii Copyright © by Andrew H. Chapman 2013 iii QUEUETOPIA: SECOND-WORLD MODERNITY AND THE SOVIET CULTURE OF ALLOCATION Andrew H. Chapman, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The social structure of the queue, from its most basic forms as a spontaneous group of people on the street, to the ordered lists of status-based priorities within society, leads to rich discussions on consumption, the behavior of crowds, and everyday life within Soviet society. By viewing how practices such as queuing were encoded in Soviet culture, the dissertation theorizes how everyday life was based on discourses of scarcity and abundance. I contend in my second chapter that second-world modernity was not predicated on the speed and calculation usually associated with modern life. -

L 51 Official Journal

ISSN 1725-2555 Official Journal L51 of the European Union Volume 50 English edition Legislation 20 February 2007 Contents I Acts adopted under the EC Treaty/Euratom Treaty whose publication is obligatory REGULATIONS Commission Regulation (EC) No 159/2007 of 19 February 2007 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables ............................... 1 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 160/2007 of 15 February 2007 concerning the classification of certain goods in the Combined Nomenclature .................................................. 3 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 161/2007 of 15 February 2007 concerning the classification of certain goods in the Combined Nomenclature .................................................. 5 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 162/2007 of 19 February 2007 amending Regulation (EC) No 2003/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council relating to fertilisers for the purposes of adapting Annexes I and IV thereto to technical progress (1) ....................... 7 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 163/2007 of 19 February 2007 fixing, for the 2005/06 marketing year, the amounts to be paid by sugar manufacturers to beet sellers in respect of the difference between the maximum amount of the base levy and the amount of that levy to be charged ........................................................................................ 16 ★ Commission Regulation (EC) No 164/2007 of 19 February 2007 fixing the production levies in the sugar sector for the 2005/06 marketing year ............................................... 17 II Acts adopted under the EC Treaty/Euratom Treaty whose publication is not obligatory DECISIONS Council 2007/117/EC: ★ Council Decision of 15 February 2007 amending the Decision of 27 March 2000 authorising the Director of Europol to enter into negotiations on agreements with third States and non-EU related bodies ................................................................................... -

The University of Chicago Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SMUGGLER STATES: POLAND, LATVIA, ESTONIA, AND CONTRABAND TRADE ACROSS THE SOVIET FRONTIER, 1919-1924 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ANDREY ALEXANDER SHLYAKHTER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2020 Илюше Abstract Smuggler States: Poland, Latvia, Estonia, and Contraband Trade Across the Soviet Frontier, 1919-1924 What happens to an imperial economy after empire? How do economics, security, power, and ideology interact at the new state frontiers? Does trade always break down ideological barriers? The eastern borders of Poland, Latvia, and Estonia comprised much of the interwar Soviet state’s western frontier – the focus of Moscow’s revolutionary aspirations and security concerns. These young nations paid for their independence with the loss of the Imperial Russian market. Łódź, the “Polish Manchester,” had fashioned its textiles for Russian and Ukrainian consumers; Riga had been the Empire’s busiest commercial port; Tallinn had been one of the busiest – and Russians drank nine-tenths of the potato vodka distilled on Estonian estates. Eager to reclaim their traditional market, but stymied by the Soviet state monopoly on foreign trade and impatient with the slow grind of trade talks, these countries’ businessmen turned to the porous Soviet frontier. The dissertation reveals how, despite considerable misgivings, their governments actively abetted this traffic. The Polish and Baltic struggles to balance the heady profits of the “border trade” against a host of security concerns shaped everyday lives and government decisions on both sides of the Soviet frontier. -

A Companion to Andrei Platonov's the Foundation

A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Studies in Russian and Slavic Literatures, Cultures and History Series Editor: Lazar Fleishman A Companion to Andrei Platonov’s The Foundation Pit Thomas Seifrid University of Southern California Boston 2009 Copyright © 2009 Academic Studies Press All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-934843-57-4 Book design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press in 2009 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com iv Effective December 12th, 2017, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. The open access publication of this volume is made possible by: This open access publication is part of a project supported by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book initiative, which includes the open access release of several Academic Studies Press volumes. To view more titles available as free ebooks and to learn more about this project, please visit borderlinesfoundation.org/open. Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Platonov’s Life . 1 CHAPTER TWO Intellectual Influences on Platonov . 33 CHAPTER THREE The Literary Context of The Foundation Pit . 59 CHAPTER FOUR The Political Context of The Foundation Pit . 81 CHAPTER FIVE The Foundation Pit Itself . -

Aes Corporation

THE AES CORPORATION THE AES CORPORATION The global power company A Passion to Serve A Passion A PASSION to SERVE 2000 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT THE AES CORPORATION 1001 North 19th Street 2000 Arlington, Virginia 22209 USA (703) 522-1315 CONTENTS OFFICES 1 AES at a Glance AES CORPORATION AES HORIZONS THINK AES (CORPORATE OFFICE) Richmond, United Kingdom Arlington, Virginia 2 Note from the Chairman 1001 North 19th Street AES OASIS AES TRANSPOWER Arlington, Virginia 22209 Suite 802, 8th Floor #16-05 Six Battery Road 5 Our Annual Letter USA City Tower 2 049909 Singapore Phone: (703) 522-1315 Sheikh Zayed Road Phone: 65-533-0515 17 AES Worldwide Overview Fax: (703) 528-4510 P.O. Box 62843 Fax: 65-535-7287 AES AMERICAS Dubai, United Arab Emirates 33 AES People Arlington, Virginia Phone: 97-14-332-9699 REGISTRAR AND Fax: 97-14-332-6787 TRANSFER AGENT: 83 2000 AES Financial Review AES ANDES FIRST CHICAGO TRUST AES ORIENT Avenida del Libertador COMPANY OF NEW YORK, 26/F. Entertainment Building 602 13th Floor A DIVISION OF EQUISERVE 30 Queen’s Road Central 1001 Capital Federal P.O. Box 2500 Hong Kong Buenos Aires, Argentina Jersey City, New Jersey 07303 Phone: 852-2842-5111 Phone: 54-11-4816-1502 USA Fax: 852-2530-1673 Fax: 54-11-4816-6605 Shareholder Relations AES AURORA AES PACIFIC Phone: (800) 519-3111 100 Pine Street Arlington, Virginia STOCK LISTING: Suite 3300 NYSE Symbol: AES AES ENTERPRISE San Francisco, California 94111 Investor Relations Contact: Arlington, Virginia USA $217 $31 Kenneth R. Woodcock 93% 92% AES ELECTRIC Phone: (415) 395-7899 $1.46* 91% Senior Vice President 89% Burleigh House Fax: (415) 395-7891 88% 1001 North 19th Street $.96* 18 Parkshot $.84* AES SÃO PAULO Arlington, Virginia 22209 Richmond TW9 2RG $21 Av.