Original Article Camels and Adaptation to Water Lack Abstract Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wild Or Bactrian Camel French: German: Wildkamel Spanish: Russian: Dikiy Verblud Chinese

1 of 4 Proposal I / 7 PROPOSAL FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIES ON THE APPENDICES OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A. PROPOSAL: Inclusion of the Wild camel Camelus bactrianus in Appendix I of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals: B. PROPONENT: Mongolia C. SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxon 1.1. Classis: Mammalia 1.2. Ordo: Tylopoda 1.3. Familia: Camelidae 1.4. Genus: Camelus 1.5. Species: Camelus bactrianus Linnaeus, 1758 1.6. Common names: English: Wild or Bactrian camel French: German: Wildkamel Spanish: Russian: Dikiy verblud Chinese: 2. Biological data 2.1. Distribution Wild populations are restricted to 3 small, remnant populations in China and Mongolia:in the Taklamakan Desert, the deserts around Lop Nur, and the area in and around region A of Mongolia’s Great Gobi Strict Protected Area (Reading et al 2000). In addition, there is a small semi-captive herd of wild camels being maintained and bred outside of the Park. 2.2. Population Surveys over the past several decades have suggested a marked decline in wild bactrian camel numbers and reproductive success rates (Zhirnov and Ilyinsky 1986, Anonymous 1988, Tolgat and Schaller 1992, Tolgat 1995). Researchers suggest that fewer than 500 camels remain in Mongolia and that their population appears to be declining (Xiaoming and Schaller 1996). Globally, scientists have recently suggested that less than 900 individuals survive in small portions of Mongolia and China (Tolgat and Schaller 1992, Hare 1997, Tolgat 1995, Xiaoming and Schaller 1996). However, most of the population estimates from both China and Mongolia were made using methods which preclude rigorous population estimation. -

Bactrian Camel, Two-Humped Camel

Camelus ferus/bactrianus Common name: Bactrian camel, two-humped camel Local name: Havtagai (Mongolian), Wildkamel (German), Jya nishpa yapung (Ladakhi) Classification: Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Artiodactyla Family: Camelidae Genus: Camelus Species: ferus/bactrianus Profile: The scientific name of the wild Bactrian camel is Camelus ferus, while the domesticated form is called Camelus bactrianus. The distinctive feature of the animal is that it is two-humped whereas the Dromedary camel has a single hump. DNA tests have revealed that there are two or three distinct genetic differences and about 3% base difference between the wild and domestic populations of Bactrian camels. They also differ physically. The wild Bactrian camel is smaller and slender than the domestic breed. The wild camels have a sandy gray- brown coat while the domestic ones have a dark brown coat. The predominant difference between them however is the shape of the humps. While that of the wild camel are small and pyramid-like, those of the domestic ones are large and irregular. The face of a Bactrian camel is long and triangular with a split upper lip. The Bactrian camel is highly adapted to surviving the cold desert climate. Each foot has an undivided sole with two large toes that can spread wide apart for walking on sand. The ears and nose are lined with hair to protect against sand and the muscular nostrils can be closed during sandstorms. The eyes are protected from sand and debris by a double layer of long eyelashes while bushy eyebrows give protection from the sun. It grows a thick shaggy coat during winter, which is shed very rapidly in spring to give the animal a shorn look. -

Characterization of Caseins from Mongolian Yak, Khainak, and Bactrian Camel B Ochirkhuyag, Jm Chobert, M Dalgalarrondo, Y Choiset, T Haertlé

Characterization of caseins from Mongolian yak, khainak, and bactrian camel B Ochirkhuyag, Jm Chobert, M Dalgalarrondo, Y Choiset, T Haertlé To cite this version: B Ochirkhuyag, Jm Chobert, M Dalgalarrondo, Y Choiset, T Haertlé. Characterization of caseins from Mongolian yak, khainak, and bactrian camel. Le Lait, INRA Editions, 1997, 77 (5), pp.601-613. hal-00929550 HAL Id: hal-00929550 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00929550 Submitted on 1 Jan 1997 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Lait (1997) 77, 601-613 601 © Eisevier/Inra Original article Characterization of caseins from Mongolian yak, khainak, and bactrian cam el B Ochirkhuyag 2, lM Chobert 1*, M Dalgalarrondo 1, Y Choiset 1, T Haertlé ' 1 Laboratoire d'étude des interactions des molécules alimentaires, Inra, rue de la Géraudière, BP 71627, 44316 Nantes cedex 03, France; 2 Institute of Chemistry, Academy of Sciences, Vlan Bator, Mongolia (Received 25 November 1996; accepted 5 May 1997) Summary - The composition of acid-precipitated caseins from ruminant Mongolian domestic ani- maIs was analyzed and a comparative study between camel (Camelus bactrianus) and dromedary (Camelus dromedarius) was realized. Acid-precipitated whole caseins were analyzed for ami no acid composition, separated by anion exchange chromatography and identified by alkaline urea-PAGE. -

{TEXTBOOK} Is a Camel a Mammal?

IS A CAMEL A MAMMAL? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tish Rabe,Jim Durk | 48 pages | 04 Jun 2001 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007111077 | English | London, United Kingdom Is a Camel a Mammal? PDF Book Ano ang katangian ng salawikain? Retrieved 5 December Camel is an animal and is not an egg laying mammal. So we had what amounted to two pounds or more of rubber for dinner that night. Is camel a marsupial mammal? What rhymes with mammal? Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement. Collared peccary P. The Oxford Companion to Food 2nd ed. Both the dromedary the seven-humped camel of Arabia and the Bactrian camel the two-humped camel of Central Asia had been domesticated since before BC. Red brocket M. In addition to providing the Roman Army with its best archers, the Easterners largely Arabs but generally known as 'Syrians' served as Rome's most effective dromedarii or camel-mounted troops. Even salty water can be tolerated, and between drinks it forages far from oases to find food unavailable to other livestock. Somalia a Country Study. White-tailed deer O. Namespaces Article Talk. Do camels lay eggs? Greenwood Publishing Group. View 1 comment. The reason why Cyrus opposed his camels to the enemy's horse was because the horse has a natural dread of the camel, and cannot abide either the sight or the smell of that animal. Archived from the original on 4 August Melissa Stewart. Camel Corps experiment. Is the word camel a short vowel word? ABC News. Consequently, these schools hold that Muslims must perform wudhu ablution before the next time they pray after eating camel meat. -

Cervid Mixed-Species Table That Was Included in the 2014 Cervid RC

Appendix III. Cervid Mixed Species Attempts (Successful) Species Birds Ungulates Small Mammals Alces alces Trumpeter Swans Moose Axis axis Saurus Crane, Stanley Crane, Turkey, Sandhill Crane Sambar, Nilgai, Mouflon, Indian Rhino, Przewalski Horse, Sable, Gemsbok, Addax, Fallow Deer, Waterbuck, Persian Spotted Deer Goitered Gazelle, Reeves Muntjac, Blackbuck, Whitetailed deer Axis calamianensis Pronghorn, Bighorned Sheep Calamian Deer Axis kuhili Kuhl’s or Bawean Deer Axis porcinus Saurus Crane Sika, Sambar, Pere David's Deer, Wisent, Waterbuffalo, Muntjac Hog Deer Capreolus capreolus Western Roe Deer Cervus albirostris Urial, Markhor, Fallow Deer, MacNeil's Deer, Barbary Deer, Bactrian Wapiti, Wisent, Banteng, Sambar, Pere White-lipped Deer David's Deer, Sika Cervus alfredi Philipine Spotted Deer Cervus duvauceli Saurus Crane Mouflon, Goitered Gazelle, Axis Deer, Indian Rhino, Indian Muntjac, Sika, Nilgai, Sambar Barasingha Cervus elaphus Turkey, Roadrunner Sand Gazelle, Fallow Deer, White-lipped Deer, Axis Deer, Sika, Scimitar-horned Oryx, Addra Gazelle, Ankole, Red Deer or Elk Dromedary Camel, Bison, Pronghorn, Giraffe, Grant's Zebra, Wildebeest, Addax, Blesbok, Bontebok Cervus eldii Urial, Markhor, Sambar, Sika, Wisent, Waterbuffalo Burmese Brow-antlered Deer Cervus nippon Saurus Crane, Pheasant Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Hog Deer, Sambar, Barasingha, Nilgai, Wisent, Pere David's Deer Sika 52 Cervus unicolor Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Barasingha, Nilgai, Rusa, Sika, Indian Rhino Sambar Dama dama Rhea Llama, Tapirs European Fallow Deer -

Prospects for Rewilding with Camelids

Journal of Arid Environments 130 (2016) 54e61 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Arid Environments journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaridenv Prospects for rewilding with camelids Meredith Root-Bernstein a, b, *, Jens-Christian Svenning a a Section for Ecoinformatics & Biodiversity, Department of Bioscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark b Institute for Ecology and Biodiversity, Santiago, Chile article info abstract Article history: The wild camelids wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus), guanaco (Lama guanicoe), and vicuna~ (Vicugna Received 12 August 2015 vicugna) as well as their domestic relatives llama (Lama glama), alpaca (Vicugna pacos), dromedary Received in revised form (Camelus dromedarius) and domestic Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) may be good candidates for 20 November 2015 rewilding, either as proxy species for extinct camelids or other herbivores, or as reintroductions to their Accepted 23 March 2016 former ranges. Camels were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. Camelids have been abundant and widely distributed since the mid-Cenozoic and were among the first species recommended for Pleistocene rewilding. They show a range of adaptations to dry and marginal habitats, keywords: Camelids and have been found in deserts, grasslands and savannas throughout paleohistory. Camelids have also Camel developed close relationships with pastoralist and farming cultures wherever they occur. We review the Guanaco evolutionary and paleoecological history of extinct and extant camelids, and then discuss their potential Llama ecological roles within rewilding projects for deserts, grasslands and savannas. The functional ecosystem Rewilding ecology of camelids has not been well researched, and we highlight functions that camelids are likely to Vicuna~ have, but which require further study. -

Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003"

NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL LIBRARY ARCHIVED FILE Archived files are provided for reference purposes only. This file was current when produced, but is no longer maintained and may now be outdated. Content may not appear in full or in its original format. All links external to the document have been deactivated. For additional information, see http://pubs.nal.usda.gov. "Information resources on old world camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003" NOTE: Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian, 1941-2004 may be viewed as one document below or by individual sections at camels2.htm Information Resources on Old United States Department of Agriculture World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1941-2004 Agricultural Research Service November 2001 (Updated December 2004) National Agricultural AWIC Resource Series No. 13 Library Compiled by: Jean Larson Judith Ho Animal Welfare Information Animal Welfare Information Center Center USDA, ARS, NAL 10301 Baltimore Ave. Beltsville, MD 20705 Contact us : http://www.nal.usda.gov/awic/contact.php Policies and Links Table of Contents Introduction About this Document Bibliography World Wide Web Resources Information Resources on Old World Camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1941-2004 Introduction The Camelidae family is a comparatively small family of mammalian animals. There are two members of Old World camels living in Africa and Asia--the Arabian and the Bactrian. There are four members of the New World camels of camels.htm[12/10/2014 1:37:48 PM] "Information resources on old world camels: Arabian and Bactrian 1962-2003" South America--llamas, vicunas, alpacas and guanacos. They are all very well adapted to their respective environments. -

Get to Know Exotic Fiber!

Get to know Exotic Fiber! In this article we will go over how camel, alpaca, yak and vicuna fiber is made into yarn. As we have all been learning, we can make fiber out of just about anything. These exotic fibers range from great everyday items to once in a lifetime chance to even see. In this article we will touch on camel, alpaca, yak and vicuna fiber. Camelids refers to the biological family that contain camels, alpacas and vicunas. In general, camelids are two-toed, longer necked, herbivores that have adapted to match their environment. Yaks are part of the bovidae family which also contain cattle, sheep, goats, antelopes and several other species. Yaks can get up to 7 feet tall and weight upwards of 1,300 pounds. Domesticated yaks are considerably smaller. Lets start with Camels! The Bactrian Camel, which produces the finest fiber, are commonly found in Mongolia. They can live up to 50 years and be over 7 feet tall at the hump. These two-humped herbivores hair is mainly imported from Mongolia. In ancient times, China, Iraq, and Afghanistan were some of the first countries to utilize camel fiber. Bactrian Camels are double coated to withstand both high mountain winters and summers in the desert sand. The coarse guard hairs can be paired with sheep wool, while the undercoat is very soft and a great insulator. Every spring Bactrian Camels naturally shed their winter coats, making it easier to turn into yarn. Back when camel caravans were the main form of transportation of people and goods, a "trailer" was a person that followed behind the caravan collecting the fibers. -

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel by Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel By Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010 50-40 million years ago (Eocene): The oldest known camel is Protylopus, appeared 40-50 million years ago (Eocene) in North America. It was the size of a rabbit and lived in the forest. Later, camels spread to the savanna and increased their size. In Oligocene, 35 million years ago, Poebrotherium was the size of a roe deer but already resembled a camel. 45-38 million years ago: The ancestors of the modern camel lived in North America. The ancestors of the lamas and camels appear to have diverged sometime in the Eocene epoch. 24-12 million years ago: Various types of camels evolved. Stenomylus was a gazelle like camel. Alticamelus, which lived 10 to 2 million years ago, had a long neck similar to a giraffe. Procamelus, just 1.2 m tall (like a modern Lama) evolved in the Camelus genus (to which modern camels belong). Lamas migrated to South America, and all the camels in North America died out. Once in Asia, camels migrated through Eastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. 3-2 million years ago: Camelus passed from North America in Asia through Behringia 2-3 million years ago. 2 million years ago: The ancestors of lama and vicuña passed into the Andes coming from North America. The last camel surviving the cradle of the camel evolution, North America, was Camelops hesternus, which disappeared 12-10,000 years ago together with the whole mega fauna of North America (mammoths, mastodons, giant sloth and saber toothed cats). -

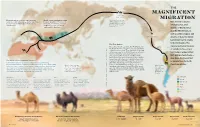

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

Migratory Species and Desertification

UNCCD thematic fact sheet series No. 6 Migratory species and desertification At any moment somewhere in the world millions of migratory animals are on the move Hoare B. (2009) Animal Migration. Remarkable Journeys in the wild. Saker Falcon © Tony Hisgett Tony © Falcon Saker Migratory species come in all shapes and sizes, from tiny insects and birds to large buffalo and elephants, to sharks and dolphins or snakes . Whether their journey crosses thousands of kilometers, or just a few, migratory species play essential roles in ecosystems worldwide. But their diverse habitats are threatened by land degradation and desertification. Over ten thousand species numbering millions of animals migrate every year, flights. The limited energy stores birds are able to accumulate might not and they face some of the highest rates of extinction. Because they are integral be enough for them to accomplish these long journeys. Some migratory to multiple ecosystems, migratory species serve as effective indicators of species can adjust to cope to some extent. For instance in Central Asia, environmental changes. the Saiga Antelope can endure severe temperature fluctuations ranging between -50 to +50°C and cover several hundred kilometres in a single day. Migratory species make many contributions to ecosystem structure and function. Migratory ungulates in Central Asia face many threats, such as over-hunting, On land, by moving between areas they inhabit at different times of the year in overgrazing by livestock, and fences that deny access to important feeding search of food, shelter and safe places to breed, they act as fertilizers, pollinators grounds, preventing the recovery of Saiga populations, Mongolian Gazelles, and seed distributors. -

A Tool We Feel Will Make Your Child's Experience at Monterey Zoo Much More Fun, Challenging, Entertaining and Best of All, Educational

Dear Parent, Welcome to Monterey Zoo's walking "ZOO QUIZ", a tool we feel will make your child's experience at Monterey Zoo much more fun, challenging, entertaining and best of all, educational. All the answers to this quiz are located on the signage in front of our habitats or within the animal's habitats themselves but all are also welcome and encouraged to ask the keepers for a clue if it helps. Depending on your child's age, your help could be necesarry on some questions or to read and explain some of the verbage on the signs. Be sure to share this activity with your schools curriculum coordinator as your visit coupled with this quiz might very will fulfill some if not several of your child's curriculum requirements in a subject. If you and/or your child have a mobile device, BE SURE TO LOOK for the QR Codes on some of the signs. They will enable you and yours to watch a fun-informative video about the animal you are seeing. Ask a keeper for help if you need it. Look for the answers on the signs outside each animal habitat and within the actual habitat. Please don't hesitate to ask a Monterey Zookeeper for a clue... but most of all, have fun! Where do Sulcata Tortoises come from? (circle one) - Africa - China - Hawaii - Los Angeles Where do Red Footed Tortoises come from? (circle one) - Africa - South America - Canada Where can Parrots be found in the wild? (circle one) - South America - Africa - Australia - All of the above Parrots can live up to (circle one) - 20 years - 50 years - 80 years - 100 years Seagulls are..