About the Alpaca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel by Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel By Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010 50-40 million years ago (Eocene): The oldest known camel is Protylopus, appeared 40-50 million years ago (Eocene) in North America. It was the size of a rabbit and lived in the forest. Later, camels spread to the savanna and increased their size. In Oligocene, 35 million years ago, Poebrotherium was the size of a roe deer but already resembled a camel. 45-38 million years ago: The ancestors of the modern camel lived in North America. The ancestors of the lamas and camels appear to have diverged sometime in the Eocene epoch. 24-12 million years ago: Various types of camels evolved. Stenomylus was a gazelle like camel. Alticamelus, which lived 10 to 2 million years ago, had a long neck similar to a giraffe. Procamelus, just 1.2 m tall (like a modern Lama) evolved in the Camelus genus (to which modern camels belong). Lamas migrated to South America, and all the camels in North America died out. Once in Asia, camels migrated through Eastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. 3-2 million years ago: Camelus passed from North America in Asia through Behringia 2-3 million years ago. 2 million years ago: The ancestors of lama and vicuña passed into the Andes coming from North America. The last camel surviving the cradle of the camel evolution, North America, was Camelops hesternus, which disappeared 12-10,000 years ago together with the whole mega fauna of North America (mammoths, mastodons, giant sloth and saber toothed cats). -

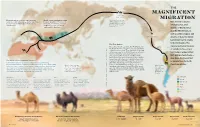

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters. -

Mammals from the Earliest Uintan

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Mammals from the earliest Uintan (middle Eocene) Turtle Bluff Member, Bridger Formation, southwestern Wyoming, USA, Part 2: Apatotheria, Lipotyphla, Carnivoramorpha, Condylartha, Dinocerata, Perissodactyla and Artiodactyla Paul C. Murphey and Thomas S. Kelly ABSTRACT The Turtle Bluff Member (TBM) of the Bridger Formation in southwestern Wyo- ming, formerly known as the Bridger E, is designated as the stratotype section for the earliest Uintan or biochron Ui1a of the Uintan North American Land Mammal age. The TBM overlies the Twin Buttes Member of the Bridger Formation, upon which the Twin- buttean Subage or biochron Br3 of the Bridgerian North American Land Mammal age is characterized. For over a century, the TBM yielded only a few fragmentary speci- mens, but extensive field work over the last 23 years has resulted in the discovery of numerous mammal fossils from the member, which provides an unprecedented oppor- tunity to better define this poorly known interval. This is the second in a series of three papers that provide detailed descriptions and taxonomic revisions of the fauna from the TBM. Here we document the occurrence of the following taxa from the TBM: Apatemys bellulus; Apatemys rodens; Scenopagus priscus; Scenopagus curtidens; Sespedecti- nae, genus undetermined; Entomolestes westgatei new species; Centetodon bemi- cophagus; Centetodon pulcher; Nyctitherium gunnelli new species; Nyctitherium velox; Pontifactor bestiola; an unnamed oligoryctid; an unnamed lipotyphlan; Viverravus grac- ilis; Hyopsodus lepidus; Uintatherium anceps; Wickia sp., cf. W. brevirhinus; Triplopus sp., cf. T. obliquidens; Epihippus sp., cf. E. gracilis; Homacodon sp., cf. H. vagans; and Merycobunodon? walshi new species. A greater understanding of the faunal composi- tion of the TBM allows a better characterization of the beginning of the Uintan and fur- ther clarifies the Bridgerian-Uintan transition. -

Spectrum of Camel Evolution and Its Impact on Ancient Human Migration

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 8 February 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202102.0176.v1 Spectrum of Camel Evolution and its Impact on Ancient Human Migration Indu Sharma1#, Jyotsna Sharma1, 2#, Sachin Kumar1, Hemender Singh2, Varun Sharma1*, Niraj Rai1* 1. Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, 226007, India 2. Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, Katra, Jammu and Kashmir, 182320, India # First Shared Authors *Corresponding Authors: Dr. Varun Sharma [email protected] Dr. Niraj Rai [email protected] Abstract The Evolutionary history and domestication of Camels are largely unexplored because of the lack of well dated early archaeological records. However, limited records suggest that domestication of Camels likely happened in the late second millennium BCE. Over the time, camels have helped human for their basic needs like meat, milk, wool, dung to long routes transportation. This multifaceted animal has helped the mankind to connect through continents and in trade majorly through the Silk route. In India, both dromedary and Bactrian camels are found and their habitat is entirely different from each other, dromedaries inhabit in hot deserts and Bactrians are found mostly in cold places (Nubra Valley, Ladakh). Fewer studies on Indian dromedaries have been conducted but no such studies are done on Bactrian camels. It is needed to study the genetics of Bactrian camels to find out their genetic affinity and evolutionary history with other Bactrians found in different parts of the world. Furthermore, parallel studies on humans and Bactrian camel are required to understand the co-evolution and migration pattern of humans during their dispersal in different time periods. -

An Assessment of the Vertebrate Paleoecology and Biostratigraphy of the Sespe Formation, Southern California

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AN ASSESSMENT OF THE VERTEBRATE PALEOECOLOGY AND BIOSTRATIGRAPHY OF THE SESPE FORMATION, SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA by Thomas M. Bown1 Open-File Report 94-630 1994 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1 USGS, Denver, Colorado Abstract Fossil vertebrates occurring in the continental Sespe Formation of southern California indicate that deposition of the upper third of the lower member and the middle and upper members of the formation took place between Uintan (middle Eocene) and late early or early late Arikareean (latest Oligocene or earliest Miocene) time. Chadronian (latest Eocene) mammalian faunas are unknown and indicate a period of intraformational erosion also substantiated by sedimentologic data. The Sespe environment was probably savannah with gallery forest that formed under a climate with wet and dry seasons. More detailed knowledge of Sespe sediment accumulation rates and paleoclimates can be obtained through paleosol and alluvial architecture studies. Introduction The continental Sespe Formation (Watts, 1897) consists of over 1,650 m of coarse to fine lithic sandstone, pebble to cobble conglomerate, and variegated mudrock and claystone that is best exposed in the Simi Valley area of the Ventura Basin, southern California. It is unconformably underlain by the largely marine Llajas Formation (lower to middle Eocene; Squires, 1981), and is variously overlain conformably (gradationally) by the Vaqueros Formation (?upper Oligocene to lower Miocene; Blake, 1983), or unconformably by the Calabasas or Modelo Formations (middle Miocene), or the Pliocene Saugus Formation (Taylor, 1983). -

Original Article Camels and Adaptation to Water Lack Abstract Introduction

MRVSA 5 (Special issue) 1st Iraqi colloquium on camel diseases and Management 2016 / College of Veterinary Medicine/ Al Muthanna University 16-17 March, 2016, 64-69 Hussein Abdullah Al-Baka, 2016 http://mrvsa.com/ ISSN 2307-8073 Mirror of Research in Veterinary Sciences and Animals (MRVSA) Original article Camels and adaptation to water lack Hussein Abdullah Al-Baka Faculty of veterinary medicine / University of Kufa Abstract The camel is truly multi-purpose animal. For hundreds of years the camel had been exploited by man in Asia and Africa in arid and semiarid areas - often being the only supplier of food and transport for people. Camel is beast of burden and provider of milk, meat, and hides. The camel has shown to be better adapted to extreme conditions in most aspects than other domestic ruminants.The camel has an exceptional tolerance to dehydration of the body. It has a low evaporation, a low output of urine, and a low loss of water with feces, so it can go a very long time without water. In severe dehydration the plasma volume of camel is only slightly reduced. The camel is able to drink in 10 minutes about one third of its body weight water. After that the camel shows no signs of water intoxication. The camel does not drink more than necessary to obtain a normal water of the body. The camel is truly multi-purpose animal. For hundreds of years the camel had been exploited by man in Asia and Africa in arid and semiarid areas - often being the only supplier of food and transport for people. -

Western Association of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting: Program with Abstracts

UC Berkeley PaleoBios Title Western Association of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting: Program with Abstracts Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fk763th Journal PaleoBios, 32(1) ISSN 0031-0298 Authors Sankey, Julia, editor Biewer, Jacob, editor Publication Date 2015-01-20 DOI 10.5070/P9321025493 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PaleoBios 32(1) Supplement:1–17, January 20, 2015 WESTERN ASSOCIATION OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ANNUAL MEETING Jacob Biewer PROGRAM WITH ABSTRACTS CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, STANISLAUS NARAGHI HALL OF SCIENCES, TURLOCK, CA FEBRUARY 14–15, 2015 Host Committee: Julia Sankey and Jacob Biewer, Sankey Paleo Lab, Geology Program, California State University, Stanislaus Citation: Sankey, J., and J. Biewer (eds.). 2015. Western Association of Vertebrate Paleontology Annual Meeting: Program with Abstracts. PaleoBios 32(1) Supplement. ucmp_paleobios_25493 Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6fk763th Copyright: Items in eScholarship are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise indicated. PALEOBIOS, VOL. 32, NUMBER 1, SUPPLEMENT, JANUARY 2015 2015 WAVP SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Registration, 7:30–8:30 AM Naraghi Hall, hallway in front of N 101 Oral presentations Naraghi Lecture Hall 101 8:30–8:45 Sankey and Welcome and opening remarks President Sheley 8:45–9:00 Inman The Table Mountain latite: Its relationship to the Mehrten Formation and California’s geologic history 9:00–9:15 Sankey et al. Giant salmon, tortoises, and other wildlife from the Mio- Pliocene Mehrten Formation, Stanislaus County, California 9:15–9:30 Biewer et al. First description of the large tortoise from the Mio-Pliocene Mehrten Formation of Stanislaus County, California 9:30–9:45 Balisi et al. -

Introduction to Camel Origin, History, Raising, Characteristics, and Wool, Hair and Skin, a Review

International Journal of Research and Innovations in Earth Science Volume 2, Issue 6, ISSN (Online) : 2394-1375 Introduction to Camel Origin, History, Raising, Characteristics, and Wool, Hair and Skin, A Review Barat Ali Zarei Yam Morteza Khomeiri Ph.D. Student of Food Science and Technology, The Associate Professor of Food Science and Technology Gorgan University of Agriculture Sciences and Natural in agriculture sciences and natural resources university Resources, Gorgan, 49138-15739, Iran of Gorgan, Iran Email: [email protected], Tell: 989378212956 Abstract – In this review, we discussed about camel origin, Table 1: Genealogy of the dromedary camel history, population, characteristics, raising and wool, hair Order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) and skin from camel. The camelides belong to order Suborder Tylopoda (pad-footed animals) Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) and sub-order Tylopoda. Family Camelidae The family Camelidae is divided into 3 genera, The old world camels (genus Camelus, one-humped camel, Camelus Subfamily Camelinae dromedarius and The Bactrian or two-humped camel, Genus Camelus Camelus bactrianus) and the new world camels (genus Lama Species Camelus dromedaries with the species L. glama, L. guanicoe, L. pacos and genus Vicugna with the species V. vicugna). The Camelini had (genus Lama with the species L. glama, L. guanicoe, L. reached Eurasia via the Bering Isthmus about 5-3 million pacos and genus Vicugna with the species V. vicugna) years ago, whereas Lamini dispersed to South America via (Wilson and Reeder, 2005) (Fig 1). The new-world Panam’s Isthmus about 3 million years ago. Scientists have been reconstructed an evolutionary life tree of the camelidae Camelidae are smaller versions of the camels and live in based on its genome sequences analysis. -

ERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II Analisi Dei

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II Analisi dei trend di taglia corporea nei mammiferi cenozoici in relazione agli assetti climatici. Dr. Federico Passaro Tutor Dr. Pasquale Raia Co-Tutor Dr. Francesco Carotenuto Do ttorato in Scienze della Terra (XXVI° Ciclo) 2013/2014 Indice. Introduzione pag. 1 Regola di Cope e specializzazione ecologica 2 - Materiali e metodi 2 - Test sull’applicabilità della regola di Cope 3 - Risultati dei test sulla regola di Cope 4 - Discussione dei risultati sulla regola di Cope 6 Habitat tracking e stasi morfologica 11 - Materiali e metodi 11 - Risultati 12 - Discussione 12 Relazione tra diversificazione fenotipica e tassonomica nei Mammiferi cenozoici 15 - Introduzione 15 - Materiali e metodi 16 - Risultati 19 - Discussione 20 Influenza della regola di Cope sull’evoluzione delle ornamentazioni in natura 24 - Introduzione 24 - Materiali e metodi 25 - Risultati 28 - Discussione 29 Considerazioni finali 33 Bilbiografia 34 Appendice 1 48 Appendice 2 65 Appendice 3 76 Appendice 4 123 Introduzione. La massa corporea di un individuo, oltre alla sua morfologia e struttura, è una delle caratteristiche che influisce maggiormente sulla sua ecologia. La variazione della taglia (body size), sia che essa diminuisca o sia che essa aumenti, porta a cambiamenti importanti nell’ecologia della specie: influisce sulla sua “longevità stratigrafica” (per le specie fossili), sulla complessità delle strutture ornamentali, sulla capacità di occupare determinati habitat, sulla grandezza degli areali che possono occupare (range size), sull’abbondanza (densità di individui) che esse possono avere in un determinato areale, sulla capacità di sfruttare le risorse, sul ricambio generazionale, sulla loro capacità di dispersione e conseguentemente sulla capacità di sopravvivere ai mutamenti ambientali (in seguito ai mutamenti si estinguono o tendono a spostarsi per seguire condizioni ecologiche ottimali – habitat tracking). -

Download a High Resolution

DENVER MUSEUM OF NATURE & SCIENCE ANNALS NUMBER 1, SEPTEMBER 1, 2009 Land Mammal Faunas of North America Rise and Fall During the Early Eocene Climatic Optimum Michael O. Woodburne, Gregg F. Gunnell, and Richard K. Stucky WWW.DMNS.ORG/MAIN/EN/GENERAL/SCIENCE/PUBLICATIONS The Denver Museum of Nature & Science Annals is an Frank Krell, PhD, Editor-in-Chief open-access, peer-reviewed scientific journal publishing original papers in the fields of anthropology, geology, EDITORIAL BOARD: paleontology, botany, zoology, space and planetary Kenneth Carpenter, PhD (subject editor, Paleontology and sciences, and health sciences. Papers are either authored Geology) by DMNS staff, associates, or volunteers, deal with DMNS Bridget Coughlin, PhD (subject editor, Health Sciences) specimens or holdings, or have a regional focus on the John Demboski, PhD (subject editor, Vertebrate Zoology) Rocky Mountains/Great Plains ecoregions. David Grinspoon, PhD (subject editor, Space Sciences) Frank Krell, PhD (subject editor, Invertebrate Zoology) The journal is available online at www.dmns.org/main/en/ Steve Nash, PhD (subject editor, Anthropology and General/Science/Publications free of charge. Paper copies Archaeology) are exchanged via the DMNS Library exchange program ([email protected]) or are available for purchase EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION: from our print-on-demand publisher Lulu (www.lulu.com). Betsy R. Armstrong: project manager, production editor DMNS owns the copyright of the works published in the Ann W. Douden: design and production Annals, which are published under the Creative Commons Faith Marcovecchio: proofreader Attribution Non-Commercial license. For commercial use of published material contact Kris Haglund, Alfred M. Bailey Library & Archives ([email protected]). -

In South of Iraq

MRVSA 5 (Special issue) 1st Iraqi colloquium on camel diseases and management 2016 / College of Veterinary Medicine/ Al Muthanna University 16-17 March, 2016, http://mrvsa.com/ ISSN 2307-8073 Mirror of Research in Veterinary Sciences and Animals (MRVSA) Original article Observations on dromedary (Arabian camel) and its diseases Karima Al-Salihi Al Muthanna University/ College of veterinary medicine Email address: [email protected] Abstract This article describes some facts regarding the dromedary, its classification, distribution and population in the world. In addition, the diseases of camels and its classification according to OIE is also described. Since, little is known about the health problem of Iraqi camels, this article plays a magnificent role in filling the knowledge gap and drawing attention towards the improvement of camel health care and its management practices. Much emphasis is given to the occurrences of abortion in the herd of camels in Iraq. Subsequently, the authors would like to give more attention to the Iraqi camels herd and enhancement its future and production performances as camels consider as the animals of the future. Keywords: Camels, Iraq, OIE, population, abortion _________________________________________________________________ To cite this article: Karima Al-Salihi (2016). Observations on dromedary (Arabian camel) and its diseases. MRVSA 5 (Special issue) 1st Iraqi colloquium on camel diseases and management. 1-10. _________________________________________________________________ Introduction Camel is the common name for large, humped, long-necked, even-toed ungulates comprising the mammalian genus Camelus of the Camelidae family. There were over 19 million camels worldwide according to FAO statistics 2008, of which: 15 million are found in Africa and 4 million in Asia. -

Evolutionary Transitions in the Fossil Record of Terrestrial Hoofed Mammals

Evo Edu Outreach (2009) 2:289–302 DOI 10.1007/s12052-009-0136-1 ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE Evolutionary Transitions in the Fossil Record of Terrestrial Hoofed Mammals Donald R. Prothero Published online: 16 April 2009 # Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 2009 Abstract In the past few decades, many new discoveries Introduction have provided numerous transitional fossils that show the evolution of hoofed mammals from their primitive ances- The hoofed mammals, or ungulates, are the third-largest tors. We can now document the origin of the odd-toed group of placental mammals alive today (after rodents and perissodactyls, their early evolution when horses, bronto- bats). Nearly all large-bodied herbivorous mammals, living theres, rhinoceroses, and tapirs can barely be distinguished, and extinct, are ungulates. These include not only familiar and the subsequent evolution and radiation of these groups groups such as the odd-toed perissodactyls (horses, rhinos, into distinctive lineages with many different species and and tapirs) and even-toed artiodactyls (pigs, peccaries, interesting evolutionary transformations through time. hippos, camels, deer, giraffes, pronghorns, cattle, sheep, Similarly, we can document the evolution of the even-toed and antelopes) but also their extinct relatives. Depending artiodactyls from their earliest roots and their great radiation upon which phylogeny is accepted, many paleontologists into pigs, peccaries, hippos, camels, and ruminants. We can also consider elephants, sirenians, and hyraxes to be trace the complex family histories in the camels and ungulates as well (see Novacek 1986, 1992; Novacek and giraffes, whose earliest ancestors did not have humps or Wyss 1986; Novacek et al. 1988; Prothero et al.