Alpaca - Evolution to the Modern Animal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Convention on Migratory Species

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP11/Inf.21 MIGRATORY 16 July 2014 SPECIES Original: English 11th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Quito, Ecuador, 4-9 November 2014 Agenda Item 23.3.1 ASSESSMENT OF GAPS AND NEEDS IN MIGRATORY MAMMALS CONSERVATION IN CENTRAL ASIA 1. In response to multiple mandates (notably Concerted and Cooperative Actions, Rec.8.23 and 9.1, Res.10.3 and 10.9), CMS has strengthened its work for the conservation of large mammals in the central Asian region and inter alia initiated a gap analysis and needs assessment, including status reports of prioritized central Asian migratory mammals to obtain a better picture of the situation in the region and to identify priorities for conservation. Range States and a large number of relevant experts were engaged in the process, and national stakeholder consultation meetings organized in several countries. 2. The Meeting Document along with the Executive Summary of the assessment is available as UNEP/CMS/COP11/Doc.23.3.1. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the Meeting. Delegates are requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. UNEP/CMS/COP11/Inf.21 Assessment of gaps and needs in migratory mammal conservation in Central Asia Report prepared for the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Financed by the Ecosystem Restoration in Central Asia (ERCA) component of the European Union Forest and Biodiversity Governance Including Environmental Monitoring Project (FLERMONECA). -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin D

45 2009 ANIMAL GENETIC ISSN 1014-2339 RESOURCES INFORMATION Special issue: International Year of Natural Fibres BULLETIN D’INFORMATION SUR LES RESSOURCES GÉNÉTIQUES ANIMALES Nume«ro spe«cial: Anne«e internationale des fibres naturelles BOLETÍN DE INFORMACIÓN SOBRE RECURSOS GENÉTICOS ANIMALES Nu«mero especial: A–o Internacional de las Fibras Naturales The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans ce produit d'information et la présentation des données qui y figurent n'impliquent de la part de l'Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique ou au stade de développement des pays, territoires, villes ou zones ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en este producto informativo y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican, de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica o nivel de desarrollo de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Fibre Recording Systems in Camelids

Renieri et al. Fibre recording systems in camelids Carlo Renieri1, Marco Antonini2 & Eduardo Frank3 1University of Camerino, Department of Veterinary Science, Via Circonvallazione 93/95, 62024 Matelica, Italy. 2ENEA Casaccia, BIOTEC AGRO, Via Anguillarese 301, S. Maria di Galeria, Roma, Italy 3SUPPRAD programme, Catholic University of Cordoba, Obispo Trejo 323, Cordoba, Argentina Keey words: fibre production, fibre characteristics, selection for fibre, suri, recording methodologies. Llama (Lama glama L.) and alpaca (Lama pacos L.) are domestic mammals classed in the Tilopods suborder together with guanaco (Lama guanicoe L.) Introduction and vicuña (Vicugna vicugna M.). Domesticated by the pre-conquest Andean cultures, they are currently used by South America Andean populations for fiber (both, llama and alpaca), meat and packing (llama) (Flores Ochoa and Mac Quarry, 1995 a, b; Bonavia, 1996). In order to improve fiber production in both the South American domestic Camelids (SAC), llama and alpaca, three different project have been funded by the European Union during the last 15th years: • PELOS FINOS, “Supported program to improve Argentinean South American Camelids fine fiber production” (EU DG 1, 1992-1995); involving Argentine, Italy and Spain; • SUPREME, “Sustainable Production of natural Resources and Management of Ecosystems: the Potential of South American Camelid Breeding in the Andean Region”, (EU DG XII, ERBIC18CT960067, 1996-2000) involving 5 South American Countries (Argentine, Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador, Peru) and 4 European -

Wool and Other Animal Fibers

WOOL AND OTHER ANIMAL FIBERS 251 it was introduced into India in the fourth century under the romantic circumstances of a marriage between Chinese and Indian royal families. At the request of Byzantine Emper- or Justinian in A.D. 552, two monks Wool and Other made the perilous journey and risked smuggling silkworm eggs out of China in the hollow of their bamboo canes, and so the secret finally left Asia. Animal Fibers Constantinople remained the center of Western silk culture for more than 600 years, although raw silk was also HORACE G. PORTER and produced in Sicily, southern Spain, BERNICE M. HORNBECK northern Africa, and Greece. As a result of military victories in the early 13 th century, Venetians obtained some silk districts in Greece. By the 14th century, the knowledge of seri- ANIMAL FIBERS are the hair, wool, culture reached England, but despite feathers, fur, or filaments from sheep, determined efforts it was not particu- goats, camels, horses, cattle, llamas, larly successful. Nor was it successful birds, fur-bearing animals, and silk- in the British colonies in the Western worms. Hemisphere. Let us consider silk first. There are three main, distinct A legend is that in China in 2640 species of silkworms—Japanese, Chi- B.C. the Empress Si-Ling Chi noticed nese, and European. Hybrids have been a beautiful cocoon in her garden and developed by crossing different com- accidentally dropped it into a basin of binations of the three. warm water. She caught the loose end The production of silk for textile of the filament that made up the co- purposes involves two operations: coon and unwound the long, lustrous Sericulture, or the raising of the silk- strand. -

Building Blocks for Sustainable Enterprises12052017.Indd

BUILDING BLOCKS FOR SUSTAINABLE ENTERPRISES Michael Berman Raul Valenzuela BUILDING BLOCKS FOR SUSTAINABLE ENTERPRISES Balancing growing demand with responsible action by Michael Berman and Raul Valenzuela Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Design in Strategic Foresight and Innovation Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2017 Michael Berman and Raul Valenzuela, 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International 2.5 Canada license. To see the license go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. COPYRIGHT NOTICE This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 2.5 Canada License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode You are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or formatAdapt — remix, transform, and build upon the materialhe licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes.ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. With the understanding that: You do not have to comply with the license for elements of the material in the public domain or where your use is permitted by an applicable exception or limitation. -

Los Camélidos Sudamericanos

Investigaciones en carne de llama LOS CAMÉLIDOS SUDAMERICANOS Celso Ayala Vargas1 El origen de los camélidos La teoría del origen de los camélidos, indica que se originaron en América del Norte hace unos 50 millones de años. Sus antepasados dieron lugar al Poebrotherium, que era del tamaño de una oveja y proliferaba alrededor de 30 millones de años. En el Mioceno, ocurren cambios morfológicos en los camélidos, quienes aumentan de tamaño y se adaptan al tipo de alimento más rústico, desarrollando el hábito del pastoreo itinerante, el cual se convierte en el medio más adecuado para la migración a través de las estepas en expansión. Hace unos cinco millones de años un grupo de camélidos avanzan hacia América del Sur y otros a través del estrecho de Bering rumbo al Asia. La evolución posterior de esta especie produjo dos géneros distintos: El Género Lama, que actualmente es nativa a lo largo de los Andes, se divide en 4 especies Lama glama (Llama), Lama pacus (alpaca), Lama guanicoe (guanaco), Vicugna vicugna (vicuña) (Cardozo, 1975) estos dos últimos en estado silvestre, y por otra parte el género Camelus, dromedarios y camellos migran al África y el Asia Central. Investigaciones arqueológicas permiten conocer ahora; que las primeras ocupaciones humanas en los Andes fueron entre 20.000 a 10.000 años y la utilización primaria de los camélidos sudamericanos (CSA) se inicia alrededor de 5.500 años. La cultura de Tiahuanaco fue la que sobresalió significativamente en la producción de llamas y alpacas (4200 a 1500 a.c.), gracias a las posibilidades ganaderas de la región, esta cultura tuvo posesión abundante de fibra y también de carne (Cardozo, 1975). -

Llama and Alpaca Management in Germany—Results of an Online Survey Among Owners on Farm Structure, Health Problems and Self-Reflection

animals Article Llama and Alpaca Management in Germany—Results of an Online Survey among Owners on Farm Structure, Health Problems and Self-Reflection Saskia Neubert *, Alexandra von Altrock, Michael Wendt and Matthias Gerhard Wagener Clinic for Swine and Small Ruminants, Forensic Medicine and Ambulatory Service, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation, 30173 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] (A.v.A.); [email protected] (M.W.); [email protected] (M.G.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: The keeping of llamas and alpacas is becoming increasingly attractive, resulting in veterinarians being consulted to an increasing extent about the treatment of individual animals or herd care and management. At present, there is little information on the maintenance practices for South American camelids in Germany and on the level of knowledge of animal owners. To gain an overview of the number of animals kept, the farming methods and management practices in alpaca and llama populations, as well as to obtain information on common population problems, a survey was conducted among owners of South American camelids. The findings can help prepare veterinarians for herd visits and serve as a basis for the discussion of current problems in South American camelid husbandry. Abstract: An online survey of llama and alpaca owners was used to collect data on the population, husbandry, feeding, management measures and health problems. A total of 255 questionnaires were evaluated. In total, 55.1% of the owners had started keeping South American camelids within the Citation: Neubert, S.; von Altrock, last six years. -

The Biology of Marine Mammals

Romero, A. 2009. The Biology of Marine Mammals. The Biology of Marine Mammals Aldemaro Romero, Ph.D. Arkansas State University Jonesboro, AR 2009 2 INTRODUCTION Dear students, 3 Chapter 1 Introduction to Marine Mammals 1.1. Overture Humans have always been fascinated with marine mammals. These creatures have been the basis of mythical tales since Antiquity. For centuries naturalists classified them as fish. Today they are symbols of the environmental movement as well as the source of heated controversies: whether we are dealing with the clubbing pub seals in the Arctic or whaling by industrialized nations, marine mammals continue to be a hot issue in science, politics, economics, and ethics. But if we want to better understand these issues, we need to learn more about marine mammal biology. The problem is that, despite increased research efforts, only in the last two decades we have made significant progress in learning about these creatures. And yet, that knowledge is largely limited to a handful of species because they are either relatively easy to observe in nature or because they can be studied in captivity. Still, because of television documentaries, ‘coffee-table’ books, displays in many aquaria around the world, and a growing whale and dolphin watching industry, people believe that they have a certain familiarity with many species of marine mammals (for more on the relationship between humans and marine mammals such as whales, see Ellis 1991, Forestell 2002). As late as 2002, a new species of beaked whale was being reported (Delbout et al. 2002), in 2003 a new species of baleen whale was described (Wada et al. -

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel by Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010

Chronology of Evolution of the Camel By Frank J. Collazo December 13, 2010 50-40 million years ago (Eocene): The oldest known camel is Protylopus, appeared 40-50 million years ago (Eocene) in North America. It was the size of a rabbit and lived in the forest. Later, camels spread to the savanna and increased their size. In Oligocene, 35 million years ago, Poebrotherium was the size of a roe deer but already resembled a camel. 45-38 million years ago: The ancestors of the modern camel lived in North America. The ancestors of the lamas and camels appear to have diverged sometime in the Eocene epoch. 24-12 million years ago: Various types of camels evolved. Stenomylus was a gazelle like camel. Alticamelus, which lived 10 to 2 million years ago, had a long neck similar to a giraffe. Procamelus, just 1.2 m tall (like a modern Lama) evolved in the Camelus genus (to which modern camels belong). Lamas migrated to South America, and all the camels in North America died out. Once in Asia, camels migrated through Eastern Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. 3-2 million years ago: Camelus passed from North America in Asia through Behringia 2-3 million years ago. 2 million years ago: The ancestors of lama and vicuña passed into the Andes coming from North America. The last camel surviving the cradle of the camel evolution, North America, was Camelops hesternus, which disappeared 12-10,000 years ago together with the whole mega fauna of North America (mammoths, mastodons, giant sloth and saber toothed cats). -

J. Theobald and Company's Extra Special Illustrated Catalogue Of

— J, THEOBALD & COMPANY’S EXTRA SPECIAL ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE OP fJflOIC Iifll^TERNS, SLIDES AND APPARATUS. (From the smallest Toy Lanterns and Slides to the most elaborate Professional Apparatus). ACTUAL MANUFACTURERS--NOT MERE DEALERS. J. THEOBALD & COMPANY, (KSTABI.ISJIKI) OVER FIFTY YEARS), Wfsl End Retail Depot : -20, CHURCH ST., KENSINGTON, W. City Warehouse (Wholesale, Retail, and Export) where address all orders ; 43, FARRINGDON ROAD, LONDON, E.C. (Opposite Earringtlon Street Station). City Telephone: -No. 6767. West End Telephone: —No. 8597. EXTRA SPECIAL ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE OF MAGIC LANTERNS, SLIDES AND APPARATUS. (From the smallest Toy Lanterns and Slides to the most elaborate Professional Apparatus.) ACTUAL MANUFACTURERS—NOT MERE DEALERS. * •1 ; SPSCIAXd N^O'TICESS issuing N our new catalogue of Magic Lanterns and Slides for the present season wish I we to draw your attention to the very large number of new slides which are contained heiein, and particularly to the Life Model sets. This catalogue now con- tains descriptions of over 100,000 slides and is supposed to be about one of the most comprehensive yet issued. We have made one price for photographic slides right throughout. It is always possible if customers want slides specially well coloured, to fedo them up to any price, but the quality mentioned in this catalogue is quite equal to those supplied by other houses in the trade. It must always be borne in mind that there are lantern slides and lantern slides, and that there are a few people not very well known in the trade, who issue a list of very low priced slides indeed, many of which are simply slides which would not be sold by any Optician with an established reputation. -

Views of Dolphins

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Humandolphin Encounter Spaces: A Qualitative Investigation of the Geographies and Ethics of Swim-with-the-Dolphins Programs Kristin L. Stewart Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES HUMAN–DOLPHIN ENCOUNTER SPACES: A QUALITATIVE INVESTIGATION OF THE GEOGRAPHIES AND ETHICS OF SWIM-WITH-THE-DOLPHINS PROGRAMS By KRISTIN L. STEWART A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Geography in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2006 Copyright © 2006 Kristin L. Stewart All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Kristin L. Stewart defended on March 2, 2006. ________________________________________ J. Anthony Stallins Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________________ Andrew Opel Outside Committee Member ________________________________________ Janet E. Kodras Committee Member ________________________________________ Barney Warf Committee Member Approved: ________________________________________________ Barney Warf, Chair, Department of Geography The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Jessica a person, not a thing iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to all those who supported, encouraged, guided and inspired me during this research project and personal journey. Although I cannot fully express the depth of my gratitude, I would like to share a few words of sincere thanks. First, thank you to the faculty and students in the Department of Geography at Florida State University. I am blessed to have found a home in geography. In particular, I would like to thank my advisor, Tony Stallins, whose encouragement, advice, and creativity allowed me to pursue and complete this project. -

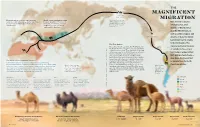

Magnificent Migration

THE MAGNIFICENT Land bridge 8 MY–14,500 Y MIGRATION Domestication of camels began between World camel population today About 6 million years ago, 3,000 and 4,000 years ago—slightly later than is about 30 million: 27 million of camelids began to move Best known today for horses—in both the Arabian Peninsula and these are dromedaries; 3 million westward across the land Camelini western Asia. are Bactrians; and only about that connected Asia and inhabiting hot, arid North America. 1,000 are Wild Bactrians. regions of North Africa and the Middle East, as well as colder steppes and Camelid ancestors deserts of Asia, the family Camelidae had its origins in North America. The The First Camels signature physical features The earliest-known camelids, the Protylopus and Lamini E the Poebrotherium, ranged in sizes comparable to of camels today—one or modern hares to goats. They appeared roughly 40 DMOR I SK million years ago in the North American savannah. two humps, wide padded U L Over the 20 million years that followed, more U L ; feet, well-protected eyes— O than a dozen other ancestral members of the T T O family Camelidae grew, developing larger bodies, . E may have developed K longer legs and long necks to better browse high C I The World's Most Adaptable Traveler? R ; vegetation. Some, like Megacamelus, grew even I as adaptations to North Camels have adapted to some of the Earth’s most demanding taller than the woolly mammoths in their time. LEWSK (Later, in the Middle East, the Syrian camel may American winters.