The Biology of Marine Mammals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

Mitochondrial Genomes of African Pangolins and Insights Into Evolutionary Patterns and Phylogeny of the Family Manidae Zelda Du Toit1,2, Morné Du Plessis2, Desiré L

du Toit et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:746 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-4140-5 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Mitochondrial genomes of African pangolins and insights into evolutionary patterns and phylogeny of the family Manidae Zelda du Toit1,2, Morné du Plessis2, Desiré L. Dalton1,2,3*, Raymond Jansen4, J. Paul Grobler1 and Antoinette Kotzé1,2,4 Abstract Background: This study used next generation sequencing to generate the mitogenomes of four African pangolin species; Temminck’s ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii), giant ground pangolin (S. gigantea), white-bellied pangolin (Phataginus tricuspis) and black-bellied pangolin (P. tetradactyla). Results: The results indicate that the mitogenomes of the African pangolins are 16,558 bp for S. temminckii, 16,540 bp for S. gigantea, 16,649 bp for P. tetradactyla and 16,565 bp for P. tricuspis. Phylogenetic comparisons of the African pangolins indicated two lineages with high posterior probabilities providing evidence to support the classification of two genera; Smutsia and Phataginus. The total GC content between African pangolins was observed to be similar between species (36.5% – 37.3%). The most frequent codon was found to be A or C at the 3rd codon position. Significant variations in GC-content and codon usage were observed for several regions between African and Asian pangolin species which may be attributed to mutation pressure and/or natural selection. Lastly, a total of two insertions of 80 bp and 28 bp in size respectively was observed in the control region of the black-bellied pangolin which were absent in the other African pangolin species. Conclusions: The current study presents reference mitogenomes of all four African pangolin species and thus expands on the current set of reference genomes available for six of the eight extant pangolin species globally and represents the first phylogenetic analysis with six pangolin species using full mitochondrial genomes. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

A new marine vertebrate assemblage from the Late Neogene Purisima Formation in Central California, part II: Pinnipeds and Cetaceans Robert W. BOESSENECKER Department of Geology, University of Otago, 360 Leith Walk, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin, 9054 (New Zealand) and Department of Earth Sciences, Montana State University 200 Traphagen Hall, Bozeman, MT, 59715 (USA) and University of California Museum of Paleontology 1101 Valley Life Sciences Building, Berkeley, CA, 94720 (USA) [email protected] Boessenecker R. W. 2013. — A new marine vertebrate assemblage from the Late Neogene Purisima Formation in Central California, part II: Pinnipeds and Cetaceans. Geodiversitas 35 (4): 815-940. http://dx.doi.org/g2013n4a5 ABSTRACT e newly discovered Upper Miocene to Upper Pliocene San Gregorio assem- blage of the Purisima Formation in Central California has yielded a diverse collection of 34 marine vertebrate taxa, including eight sharks, two bony fish, three marine birds (described in a previous study), and 21 marine mammals. Pinnipeds include the walrus Dusignathus sp., cf. D. seftoni, the fur seal Cal- lorhinus sp., cf. C. gilmorei, and indeterminate otariid bones. Baleen whales include dwarf mysticetes (Herpetocetus bramblei Whitmore & Barnes, 2008, Herpetocetus sp.), two right whales (cf. Eubalaena sp. 1, cf. Eubalaena sp. 2), at least three balaenopterids (“Balaenoptera” cortesi “var.” portisi Sacco, 1890, cf. Balaenoptera, Balaenopteridae gen. et sp. indet.) and a new species of rorqual (Balaenoptera bertae n. sp.) that exhibits a number of derived features that place it within the genus Balaenoptera. is new species of Balaenoptera is relatively small (estimated 61 cm bizygomatic width) and exhibits a comparatively nar- row vertex, an obliquely (but precipitously) sloping frontal adjacent to vertex, anteriorly directed and short zygomatic processes, and squamosal creases. -

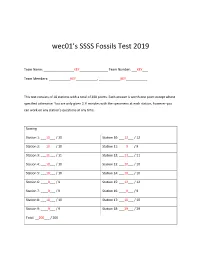

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(S): Richard C

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert, Jr., Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire Source: Journal of Paleontology , Sep., 1998, Vol. 72, No. 5 (Sep., 1998), pp. 907-927 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Paleontology This content downloaded from 131.204.154.192 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 18:43:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms J. Paleont., 72(5), 1998, pp. 907-927 Copyright ? 1998, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/98/0072-0907$03.00 A NEW MIDDLE EOCENE PROTOCETID WHALE (MAMMALIA: CETACEA: ARCHAEOCETI) AND ASSOCIATED BIOTA FROM GEORGIA RICHARD C. HULBERT, JR.,1 RICHARD M. PETKEWICH,"4 GALE A. -

PDF of Manuscript and Figures

The triple origin of whales DAVID PETERS Independent Researcher 311 Collinsville Avenue, Collinsville, IL 62234, USA [email protected] 314-323-7776 July 13, 2018 RH: PETERS—TRIPLE ORIGIN OF WHALES Keywords: Cetacea, Mysticeti, Odontoceti, Phylogenetic analyis ABSTRACT—Workers presume the traditional whale clade, Cetacea, is monophyletic when they support a hypothesis of relationships for baleen whales (Mysticeti) rooted on stem members of the toothed whale clade (Odontoceti). Here a wider gamut phylogenetic analysis recovers Archaeoceti + Odontoceti far apart from Mysticeti and right whales apart from other mysticetes. The three whale clades had semi-aquatic ancestors with four limbs. The clade Odontoceti arises from a lineage that includes archaeocetids, pakicetids, tenrecs, elephant shrews and anagalids: all predators. The clade Mysticeti arises from a lineage that includes desmostylians, anthracobunids, cambaytheres, hippos and mesonychids: none predators. Right whales are derived from a sister to Desmostylus. Other mysticetes arise from a sister to the RBCM specimen attributed to Behemotops. Basal mysticetes include Caperea (for right whales) and Miocaperea (for all other mysticetes). Cetotheres are not related to aetiocetids. Whales and hippos are not related to artiodactyls. Rather the artiodactyl-type ankle found in basal archaeocetes is also found in the tenrec/odontocete clade. Former mesonychids, Sinonyx and Andrewsarchus, nest close to tenrecs. These are novel observations and hypotheses of mammal interrelationships based on morphology and a wide gamut taxon list that includes relevant taxa that prior studies ignored. Here some taxa are tested together for the first time, so they nest together for the first time. INTRODUCTION Marx and Fordyce (2015) reported the genesis of the baleen whale clade (Mysticeti) extended back to Zygorhiza, Physeter and other toothed whales (Archaeoceti + Odontoceti). -

Place Names Describing Fossils in Oral Traditions

Place names describing fossils in oral traditions ADRIENNE MAYOR Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Folk explanations of notable geological features, including fossils, are found around the world. Observations of fossil exposures (bones, footprints, etc.) led to place names for rivers, mountains, valleys, mounds, caves, springs, tracks, and other geological and palaeonto- logical sites. Some names describe prehistoric remains and/or refer to traditional interpretations of fossils. This paper presents case studies of fossil-related place names in ancient and modern Europe and China, and Native American examples in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Evidence for the earliest known fossil-related place names comes from ancient Greco-Roman and Chinese literature. The earliest documented fossil-related place name in the New World was preserved in a written text by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. In many instances, fossil geonames are purely descriptive; in others, however, the mythology about a specific fossil locality survives along with the name; in still other cases the geomythology is suggested by recorded traditions about similar palaeontological phenomena. The antiquity and continuity of some fossil-related place names shows that people had observed and speculated about miner- alized traces of extinct life forms long before modern scientific investigations. Traditional place names can reveal heretofore unknown geomyths as well as new geologically-important sites. Traditional folk names for geological features in the Named fossil sites in classical antiquity landscape commonly refer to mythological or and modern Greece legendary stories that accounted for them (Vitaliano 1973). Landmarks notable for conspicuous fossils Evidence for the practice of naming specific fossil have been named descriptively or mythologically locales can be found in classical antiquity. -

Letter to K. Baker, 1-29-07

Marine Mammal Commission 4340 East-West Highway, Room 905 Bethesda, MD 20814 29January 2007 Mr. Kyle Baker National Marine Fisheries Service 263 13th Avenue, South St. Petersburg, FL 33701 Dear Mr. Baker: The Marine Mammal Commission, in consultation with its Committee of Scientific Advisors on Marine Mammals, has reviewed the National Marine Fisheries Service’s 29 November 2006 Federal Register notice announcing its intent to conduct a review of the Caribbean monk seal, Monachus tropicalis, under the Endangered Species Act and requesting information on the species’ status. We have reviewed our files and, with great regret, we have concluded that the species is extinct and should be removed from the list of endangered and threatened species. Fossil and archeological evidence, along with sighting records, indicate that the species once occurred from the southeastern United States through the Bahamas and the Caribbean Sea. A review of those records by Rice (1973) concluded that the last authoritative sighting was of a small colony of animals at Seranilla Banks between Jamaica and the Yucatan Peninsula in 1952. A few other unconfirmed sightings were reported from the 1950s into the 1970s, but at least some of those were reported to involve escaped California sea lions (Gunter 1968 cited in Rice 1973). Although the species may have been extinct when the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973, the Marine Mammal Commission wrote to the National Marine Fisheries Service on 26 January 1977 recommending that the Caribbean monk seal be listed as “endangered” under the Endangered Species Act and “depleted” under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. -

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes by Ryan Matthew Bebej A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip D. Gingerich, Co-Chair Professor Philip Myers, Co-Chair Professor Daniel C. Fisher Professor Paul W. Webb © Ryan Matthew Bebej 2011 To my wonderful wife Melissa, for her infinite love and support ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank each of my committee members. I will be forever grateful to my primary mentor, Philip D. Gingerich, for providing me the opportunity of a lifetime, studying the very organisms that sparked my interest in evolution and paleontology in the first place. His encouragement, patience, instruction, and advice have been instrumental in my development as a scholar, and his dedication to his craft has instilled in me the importance of doing careful and solid research. I am extremely grateful to Philip Myers, who graciously consented to be my co-advisor and co-chair early in my career and guided me through some of the most stressful aspects of life as a Ph.D. student (e.g., preliminary examinations). I also thank Paul W. Webb, for his novel thoughts about living in and moving through water, and Daniel C. Fisher, for his insights into functional morphology, 3D modeling, and mammalian paleobiology. My research was almost entirely predicated on cetacean fossils collected through a collaboration of the University of Michigan and the Geological Survey of Pakistan before my arrival in Ann Arbor. -

Thewissen Et Al. Reply Replying To: J

NATURE | Vol 458 | 19 March 2009 BRIEF COMMUNICATIONS ARISING Hippopotamus and whale phylogeny Arising from: J. G. M. Thewissen, L. N. Cooper, M. T. Clementz, S. Bajpai & B. N. Tiwari Nature 450, 1190–1194 (2007) Thewissen etal.1 describe new fossils from India that apparentlysupport fossils, Raoellidae or the raoellid Indohyus is more closely related to a phylogeny that places Cetacea (that is, whales, dolphins, porpoises) as Cetacea than is Hippopotamidae (Fig. 1). Hippopotamidae is the the sister group to the extinct family Raoellidae, and Hippopotamidae exclusive sister group to Cetacea plus Raoellidae in the analysis that as more closely related to pigs and peccaries (that is, Suina) than to down-weights homoplastic characters, althoughin the equallyweighted cetaceans. However, our reanalysis of a modified version of the data set analysis, another topology was equally parsimonious. In that topology, they used2 differs in retaining molecular characters and demonstrates Hippopotamidae moved one node out, being the sister group to an that Hippopotamidae is the closest extant family to Cetacea and that Andrewsarchus, Raoellidae and Cetacea clade. In neither analysis is raoellids are the closest extinct group, consistent with previous phylo- Hippopotamidae closer to the pigs and peccaries than to Cetacea, the genetic studies2,3. This topology supports the view that the aquatic result obtained by Thewissen et al.1. In all our analyses, pachyostosis adaptations in hippopotamids and cetaceans are inherited from their (thickening) of limb bones and bottom walking, which occur in hippo- common ancestor4. potamids9,10, are interpreted to have evolved before the pachyostosis of To conduct our analyses, we started with the same published matrix the auditory bulla, as seen in raoellids and cetaceans1. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

DESCRIPTION OF TWO SQUALODONTS RECENTLY DIS- COVERED IN THE CALVERT CLIFFS, ^LVRYLAND; AND NOTES ON THE SHARK-TOOTHED CETACEANS. By Remington Kellogg, Of the Bureau of Biological Survey, United States Departynent of Agriculture. INTRODUCTION. When the study of paleontology was less advanced than it is at present, any announcement of the discovery of prehistoric animals unlike the living indigenous fauna was usually received with some suspicion. In spite of this distrust, many attempts were made by the early writers to explain the presence of fossil remains of marine mammals in strata above the sea level or at some distance from the seashore. In one of these treatises ' is found what is, apparently, the first notice of the occurrence of fossil remains referable to shark- toothed cetaceans. The author of this work figures a fragment of a mandible, obtained from the tufa of Malta, which possesses three serrate double-rooted molar teeth. Squalodonts as such were first brought to the attention of ]mleon- tologists in 1840, by J. P. S. Grateloup, ' a French naturalist primarily interested in marine invertebrates. In the original description of Squalodon, Grateloup held the view that this rostral fragment from Leognan, France, belonged to some large saurian related to Iguanodon. Following the anouncement of this discovery. Von Meyer ^ called at- tention to the teeth of this fossil, and concluded that the specimen was referable to some flesh-eating cetacean. A year later, Grateloup* concurred in this opinion. One other specimen should be mentioned in this connection, but, unfortunately, its relationships are quite uncer- tain. This specimen consists of a single tooth which was thought to bear resemblance to some pinniped by Von Meyer ^ and named Pachy- odon mirahilis. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana ISSN: 1405-3322 Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. Hernández Cisneros, Atzcalli Ehécatl; González Barba, Gerardo; Fordyce, Robert Ewan Oligocene cetaceans from Baja California Sur, Mexico Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, vol. 69, no. 1, January-April, 2017, pp. 149-173 Sociedad Geológica Mexicana, A.C. Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=94350664007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana / 2017 / 149 Oligocene cetaceans from Baja California Sur, Mexico Atzcalli Ehécatl Hernández Cisneros, Gerardo González Barba, Robert Ewan Fordyce ABSTRACT Atzcalli Ehecatl Hernández Cisneros ABSTRACT RESUMEN [email protected] Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, Univer- Baja California Sur has an import- Baja California Sur tiene un importante re- sidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, ant Cenozoic marine fossil record gistro de fósiles marinos del Cenozoico que Carretera al Sur Km 5.5, Apartado Postal which includes diverse but poorly incluye los restos poco conocidos de cetáceos 19-B, C.P. 23080, La Paz, Baja California Sur, México. known Oligocene cetaceans from del Oligoceno de México. En este estudio Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Inter- Mexico. Here we review the cetacean ofrecemos más detalles sobre estos fósiles de disciplinario de Ciencias Marinas (CICMAR), fossil record including new observa- cetáceos, incluyendo nuevas observaciones Av. Instituto Politécnico Nacional s/n, Col.