Ossian and the Highland Tour, 1760-1805

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

The Hudson River School

Art, Artists and Nature: The Hudson River School The landscape paintings created by the 19 th century artist known as the Hudson River School celebrate the majestic beauty of the American wilderness. Students will learn about the elements of art, early 19 th century American culture, the creative process, environmental concerns and the connections to the birth of American literature. New York State Standards: Elementary, Intermediate, and Commencement The Visual Arts – Standards 1, 2, 3, 4 Social Studies – Standards 1, 3 ELA – Standards 1, 3, 4 BRIEF HISTORY By the mid-nineteenth century, the United States was no longer the vast, wild frontier it had been just one hundred years earlier. Cities and industries determined where the wilderness would remain, and a clear shift in feeling toward the American wilderness was increasingly ruled by a new found reverence and longing for the undisturbed land. At the same time, European influences - including the European Romantic Movement - continued to shape much of American thought, along with other influences that were distinctly and uniquely American. The traditions of American Indians and their relationship with nature became a recognizable part of this distinctly American Romanticism. American writers put words to this new romantic view of nature in their works, further influencing the evolution of American thought about the natural world. It found means of expression not only in literature, but in the visual arts as well. A focus on the beauty of the wilderness became the passion for many artists, the most notable came to be known as the Hudson River School Artists. The Hudson River School was a group of painters, who between 1820s and the late nineteenth century, established the first true tradition of landscape painting in the United States. -

557832 Bk Schubert US 2/13/08 1:17 PM Page 8

557832 bk Schubert US 2/13/08 1:17 PM Page 8 Nikolaus Friedrich DEUTSCHE The clarinettist Nikolaus Friedrich studied with Hermut Giesser and Karl-Heinz Lautner at SCHUBERT-LIED-EDITION • 26 the Musikhochschulen in Düsseldorf and Stuttgart. After graduating with distinction he participated in master-classes in England with Thea King and Anthony Pay. Since 1984 he has been principal clarinettist in the Mannheim National Theatre Orchestra. In addition to appearances as a soloist at the Würzburg Mozart Festival and the Berlin Festival Weeks, he is active in chamber music, appearing with the Nomos, Henschel and Mandelring Quartets, Trio Opus 8, and with his duo partner Thomas Palm. He is strongly involved in the performance of SCHUBERT contemporary music. Photo courtesy of the artist Romantic Poets, Vol. 3 Sibylla Rubens, Soprano • Ulrich Eisenlohr, Piano Ulrich Eisenlohr Nikolaus Friedrich, Clarinet The pianist Ulrich Eisenlohr is the artistic leader of the Naxos Deutsche Schubert Lied Edition. He studied piano with Rolf Hartmann at the conservatory of music in Heidelberg/Mannheim and Lieder under Konrad Richter at Stuttgart. Specialising in the areas of song accompaniment and chamber music, he began an extensive concert career with numerous instrumental and vocal partners in Europe, America and Japan, with appearances at the Vienna Musikverein and Konzerthaus, the Berlin Festival Weeks, the Kulturzentrum Gasteig in Munich, the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Edinburgh Festival, the Frankfurt Festival, the International Beethoven Festival Bonn and the Photo: Wolfgang Detering Ludwigsburg Festival, the European Music Festival Stuttgart among many others. His Lieder partners include Hans Peter Blochwitz, Christian Elsner, Matthias Görne, Dietrich Henschel, Wolfgang Holzmair, Christoph Pregardien, Roman Trekel, Rainer Trost, Iris Vermillion, Michael Volle and Ruth Ziesak among others. -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

Adam Mickiewicz's

Readings - a journal for scholars and readers Volume 1 (2015), Issue 2 Adam Mickiewicz’s “Crimean Sonnets” – a clash of two cultures and a poetic journey into the Romantic self Olga Lenczewska, University of Oxford The paper analyses Adam Mickiewicz’s poetic cycle ‘Crimean Sonnets’ (1826) as one of the most prominent examples of early Romanticism in Poland, setting it across the background of Poland’s troubled history and Mickiewicz’s exile to Russia. I argue that the context in which Mickiewicz created the cycle as well as the final product itself influenced the way in which Polish Romanticism developed and matured. The sonnets show an internal evolution of the subject who learns of his Romantic nature and his artistic vocation through an exploration of a foreign land, therefore accompanying his physical journey with a spiritual one that gradually becomes the main theme of the ‘Crimean Sonnets’. In the first part of the paper I present the philosophy of the European Romanticism, situate it in the Polish historical context, and describe the formal structure of the Crimean cycle. In the second part of the paper I analyse five selected sonnets from the cycle in order to demonstrate the poetic journey of the subject-artist, centred around the epistemological difference between the Classical concept of ‘knowing’ and the Romantic act of ‘exploring’. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to present Adam Mickiewicz's “Crimean Sonnets” cycle – a piece very representative of early Polish Romanticism – in the light of the social and historical events that were crucial for the rise of Romantic literature in Poland, with Mickiewicz as a prize example. -

Painting Time: the Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2013 Volume 19 © The Scottish Records Association Painting Time: The Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay Anne MacLeod This article examines sketches and drawings of the Highlands by John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85), who is now largely remembered for his contribution to folklore studies in the north-west of Scotland. An industrious polymath, with interests in archaeology, ethnology and geological science, Campbell was also widely travelled. His travels in Scotland and throughout the world were recorded in a series of journals, meticulously assembled over several decades. Crammed with cuttings, sketches, watercolours and photographs, the visual element within these volumes deserves to be more widely known. Campbell’s drawing skills were frequently deployed as an aide-memoire or functional tool, designed to document his scientific observations. At the same time, we can find within the journals many pioneering and visually appealing depictions of upland and moorland scenery. A tension between documenting and illuminating the hidden beauty of the world lay at the heart of Victorian aesthetics, something the work of this gentleman amateur illustrates to the full. Illustrated travel diaries are one of the hidden treasures of family archives and manuscript collections. They come in many shapes and forms: legible and illegible, threadbare and richly bound, often illustrated with cribbed engravings, hasty sketches or careful watercolours. Some mirror their published cousins in style and layout, and were perhaps intended for the print market; others remain no more than private or family mementoes. This paper will examine the manuscript journals of one Victorian scholar, John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85). -

The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism

CHAPTER 6 The Concept of Bildung in Early German Romanticism 1. Social and Political Context In 1799 Friedrich Schlegel, the ringleader of the early romantic circle, stated, with uncommon and uncharacteristic clarity, his view of the summum bonum, the supreme value in life: “The highest good, and [the source of] ev- erything that is useful, is culture (Bildung).”1 Since the German word Bildung is virtually synonymous with education, Schlegel might as well have said that the highest good is education. That aphorism, and others like it, leave no doubt about the importance of education for the early German romantics. It is no exaggeration to say that Bildung, the education of humanity, was the central goal, the highest aspiration, of the early romantics. All the leading figures of that charmed circle—Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel, W. D. Wackenroder, Friedrich von Hardenberg (Novalis), F. W. J. Schelling, Ludwig Tieck, and F. D. Schleiermacher—saw in education their hope for the redemption of humanity. The aim of their common journal, the Athenäum, was to unite all their efforts for the sake of one single overriding goal: Bildung.2 The importance, and indeed urgency, of Bildung in the early romantic agenda is comprehensible only in its social and political context. The young romantics were writing in the 1790s, the decade of the cataclysmic changes wrought by the Revolution in France. Like so many of their generation, the romantics were initially very enthusiastic about the Revolution. Tieck, Novalis, Schleiermacher, Schelling, Hölderlin, and Friedrich Schlegel cele- brated the storming of the Bastille as the dawn of a new age. -

Bards, Ballads, and Barbarians in Jena. Germanic Medievalism in The

Møller, Journal for the Study of Romanticisms (2019), Volume 08, DOI 10.14220/jsor.2019.8.1.13 Andreas Hjort Møller (AarhusUniversity) Bards,Ballads, and Barbarians in Jena. Germanic Medievalism in the Early Works of Friedrich Schlegel Abstract The early German romantics were highly interested in medieval literature,primarily poetry written in romance vernacularssuch as Dante’s Inferno. Only later did the German ro- mantics turn to northern medieval literature for inspiration. In the case of German romantic Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829), the usual opinionisthat he would not havecared for northern (primarily Scandinavian) medieval literature and art before his late phase, be- ginning around 1802. In this phase,his literary criticism stood under the sway of his con- servativepolitics. Thisarticle examines the reception of Germanic medieval literature in Schlegel’searly essays,reviews and fragments, in order to discuss the role of Germanic medieval literature in his work and the extent to which it is connectedwith his poetics and politics. Keywords Friedrich Schlegel, Medievalism, romanticism,Germanic and romance medieval literature, Antiquarianism. Traditional histories of literary criticism inform us that Friedrich Schlegel began his literary career as aclassicist historian of Greek and Roman Literature (1794– 1796), then went on to study romance literature (1797–1801) and only later, during his time in Paris around 1802, gained an interest in Germanic medieval literature that would persist for the remainder of his life.1 Schlegel’sinterest in the medieval is commonly taken to haveemerged from his so-called conservativeor nationalist turn that culminated in Schlegel’sconversion to Catholicism in the Cologne Cathedral in 1808 and his participation in the Congress of Vienna as a 1For instance, Kozielekdatesthe beginning of the interest of theearly German romantics to Ludwig Tieck and the year 1801, even though he notesthat Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder payedattention to OldGerman literature in the 1790s, Gerard Kozielek: Mittel- alterrezeption. -

Scottish Birds

Scottish Birds ~~.. :~"."~ '''·;;;i;:;U;jU-_ . .. _ _.u.::,-::": _• .••• :.".;U.... ~ . ... ~. " .- :, .. ~~.~;;:;~~;~~;:.~::::::;:'~ The Journal of The Scottish Ornithologists' Club Vol. 4 No. 1 Spring 1966 FIVE SHILLINGS Zeiss Binoculars of entirely new design: Dialyt 8x30B giving equal performance with or without spectacles This delightfully elegant and compact new model from Carl Zeiss has an entirely new prism system which gives an amazing reduction in size. The special design also gives the fullest field of view-1 30 yards at 1 ODD-to spectacle wearers and to the naked eye alike. Price £53.10.0 fl1 h dt Write for the latest camera. binocular !Ul ~ egen ar and sunglass booklets to the sole , U.K. Importers. DEGENHARDT & CO lTD CARl ZEISS HOUSE 20/22 Mortimer Street· london, W.1 ?-.IUS 8050 (9 lines) CHOOSING A BINOCULAR OR A TELESCOPE EXPERT ADVICE From a Large Selection ... New and Secondhand G. HUTCHISON & SONS Phone CAL. 5579 OPTICIANS 18 FORREST ROAD, EDINBURGH Open till 5.30 p.m. Saturdays : Early closing Tuesday COLOUR BIRD BOOKS SLIDES of BIRDS Please support Incomparable Collection of THE S.O.C. British, European and African birds. Also views and places BIRD BOOKSHOP throughout the world. Send by buying all your new stamp for list. Sets of 100 for hire. Bird Books from THE SCOTTISH CENTRE BINOCULARS FOR ORNITHOLOGY AND BIRD PROTECTION Our "Birdwatcher 8 x 30" 21 Regent Terrace, model is made to our own specifications-excellent value Edinburgh 7 at 15 gns. Handy and practical to use. Ross, Barr and Stroud, Zeiss, All books sent post free Bosch Binoculars in stock. -

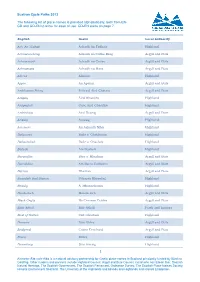

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise.