Succeed in Becoming Socialist, Excluding in That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia Geographically, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam are situated in the fastest growing region in the world, positioned alongside the dynamic economies of neighboring China and Thailand. Revolution, Reform and Regionalism in Southeast Asia compares the postwar political economies of these three countries in the context of their individual and collective impact on recent efforts at regional integration. Based on research carried out over three decades, Ronald Bruce St John highlights the different paths to reform taken by these countries and the effect this has had on regional plans for economic development. Through its comparative analysis of the reforms implemented by Cam- bodia, Laos and Vietnam over the last 30 years, the book draws attention to parallel themes of continuity and change. St John discusses how these countries have demonstrated related characteristics whilst at the same time making different modifications in order to exploit the strengths of their individual cultures. The book contributes to the contemporary debate over the role of democratic reform in promoting economic devel- opment and provides academics with a unique insight into the political economies of three countries at the heart of Southeast Asia. Ronald Bruce St John earned a Ph.D. in International Relations at the University of Denver before serving as a military intelligence officer in Vietnam. He is now an independent scholar and has published more than 300 books, articles and reviews with a focus on Southeast Asia, -

The Communist Party's Crackdown on Religion In

THE COMMUNIST PARTY’S CRACKDOWN ON RELIGION IN CHINA HEARING BEFORE THE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION NOVEMBER 28, 2018 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available at www.cecc.gov or www.govinfo.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 33–238 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 20:14 May 14, 2019 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\33238.TXT DAVID CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Senate House MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Chairman CHRIS SMITH, New Jersey, Cochairman TOM COTTON, Arkansas ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TODD YOUNG, Indiana TIM WALZ, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TED LIEU, California JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon GARY PETERS, Michigan ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Not yet appointed ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Staff Director PAUL B. PROTIC, Deputy Staff Director (ii) VerDate Nov 24 2008 20:14 May 14, 2019 Jkt 081003 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 C:\USERS\DSHERMAN1\DESKTOP\33238.TXT DAVID CONTENTS STATEMENTS Page Opening Statement of Hon. Marco Rubio, a U.S. Senator from Florida; Chair- man, Congressional-Executive Commission on China ...................................... 1 Statement of Hon. Christopher Smith, a U.S. Representative from New Jer- sey; Cochairman, Congressional-Executive Commission on China .................. 4 Tursun, Mihrigul, Uyghur Muslim detained in Chinese ‘‘reeducation’’ camp .... 6 Hoffman, Dr. Samantha, Visiting Academic Fellow, Mercator Institute for China Studies and Non-Resident Fellow, Australian Strategic Policy Insti- tute ........................................................................................................................ 8 Farr, Dr. -

Moldova: Background and U.S

Moldova: Background and U.S. Policy Steven Woehrel Specialist in European Affairs August 27, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21981 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Moldova: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Although a small country, Moldova has been of interest to U.S. policymakers due to its position between NATO and EU member Romania and strategic Ukraine. In addition, some experts have expressed concern about alleged Russian efforts to extend its hegemony over Moldova through various methods, including a troop presence, manipulation of Moldova’s relationship with its breakaway Transnistria region, and energy supplies and other economic links. Moldova’s political and economic weakness has made it a source of organized criminal activity of concern to U.S. policymakers, including trafficking in persons. From 2009 until March 2012, Moldova suffered a protracted political and constitutional crisis, over the inability of the parliament to secure a needed supermajority to elect a president. The dispute triggered three parliamentary elections in two years. Finally, in March 2012, the Moldovan parliament elected as president Nicolae Timofti, a judge with a low political profile. Prime Minister Vlad Filat has said he is focused on dismantling the country’s Communist legacy and building a state ruled by law. Moldova is Europe’s poorest country, according to the World Bank. Living standards are low for many Moldovans, particularly in rural areas. Remittances from Moldovans working abroad amounted to 22% of the country’s Gross Domestic Product in 2010. The global financial crisis has had a negative impact on Moldova. -

Representations of Unity in Soviet Symbolism

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Previously Published Works Title Soiuz and Symbolic Union: Representations of Unity in Soviet Symbolism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6mk5f6c8 Author Platoff, Anne M. Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Representations of Unity in Soviet Symbolism 23 Soiuz and Symbolic Union: Representations of Unity in Soviet Symbolism Anne M. Platoff Abstract “Soiuz”1 in Russian means “union”—a key word in the formal name of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Once the world’s largest state, the Soviet Union comprised 15 republics and more than 100 distinct ethnic groups. The country celebrated its diversity while at the same time emphasizing the unity of all Soviet peoples. Throughout the 1922–1991 history of the USSR a highly- developed system of symbolic representations was used to portray the strength of the union. For example, the state emblem visually bound the Soviet repub- lics to the state through a heraldic ribbon using all the titular languages of the republics. Likewise, the national anthem celebrated the “unbreakable union of free republics”. The Soviet symbol set also included unique, but visually unifying, symbols to represent the 15 union republics—their flags, emblems, and anthems. There were also flags for the autonomous republics within these union republics, based upon the republic flags. In addition to the symbolic portrayal of the cohesiveness of the Soviet Union, there were two other types of “unions” that were vital to Soviet symbolism—the unity of workers and peasants, as well as the brotherhood of all the world’s communists. -

ROCK MUSIC and NATIONAL IDENTITY in HUNGARY Kathryn Milun

Document generated on 09/26/2021 9:40 a.m. Surfaces ROCK MUSIC AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN HUNGARY Kathryn Milun Volume 1, 1991 Article abstract Marxism and nationalism. The political form and meaning of the discourse of URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1065258ar national identity in Hungary as it appears in popular culture. Hungarian rock DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1065258ar and shamanpunk. The debate over the national flag. See table of contents Publisher(s) Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal ISSN 1188-2492 (print) 1200-5320 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Milun, K. (1991). ROCK MUSIC AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN HUNGARY. Surfaces, 1. https://doi.org/10.7202/1065258ar Copyright © Kathryn Milun, 1991 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ROCK MUSIC AND NATIONAL IDENTITY IN HUNGARY Kathryn Milun[*] ABSTRACT Marxism and nationalism. The political form and meaning of the discourse of national identity in Hungary as it appears in popular culture. Hungarian rock and shamanpunk. The debate over the national flag. RÉSUMÉ Marxisme et nationalisme. La forme et la signification du discours d'identité nationale en Hongrie tel qu'il apparait dans la culture populaire. -

Laos, August 2004

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Laos, August 2004 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

Comrade Warhol

Edinburgh Research Explorer Comrade Warhol Citation for published version: Davis, G 2016, 'Comrade Warhol', Journal of European Popular Culture, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 107-122. https://doi.org/10.1386/jepc.7.2.107_1 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1386/jepc.7.2.107_1 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of European Popular Culture General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Comrade Warhol Essay for ‘Warhol in Europe’ issue of JEPC Glyn Davis, University of Edinburgh In a 1977 interview with Glenn O’Brien for High Times magazine, Andy Warhol was asked about his current painting projects. His response outlined a political theme connecting together works made across the decade: We’ve been in Italy so much, and everybody’s always asking me if I’m a Communist because I’ve done Mao. So now I’m doing hammers and sickles for Communism, and skulls for Fascism. (Goldsmith 2004: 239) This brief comment serves to link two of Warhol’s major groups of works of the 1970s, the Skull and Hammer and Sickle series; it also partially reprises Warhol’s common tactic of attributing creative ideas to others, the notion of making ‘Communist paintings’ here seeming to originate with unidentified interrogators. -

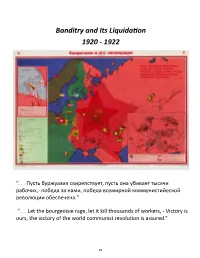

Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic Print, 64 X 102 Cm

Banditry and Its Liquidation 1920 - 1922 “. Пусть буржуазия свирепствует, пусть она убивает тысячи рабочих,- победа за нами, победа всемирной коммунистийеской революции обеспечена.” “. Let the bourgeoisie rage, let it kill thousands of workers, - Victory is ours, the victory of the world communist revolution is assured.” 62 Map 10 Banditry and Its Liquidation // 1920 - 1922 Colored Lithographic print, 64 x 102 cm. Compilers: A. N. de-Lazari and N. N. Lesevitskii Artist: S. R. Zelikhman Historical Background and Thematic Design The Russian Civil War did not necessarily end with the defeat of the Whites. Its final stage involved various independent bands of partisans and rebels that took advantage of the chaos enveloping the country and contin- ued to operate in rural areas of Ukraine, Tambov Province, the lower Volga, and western Siberia, where Bol- shevik authority was more or less tenuous. Their leaders were by and large experienced military men who stoked peasant hatred for centralized authority, whether it was German occupation forces, Poles, Moscow Bol- sheviks, or Jews. They squared off against the growing power of the communists, which is illustrated as series of five red stars extending over all four sectors. The red circle identifies Moscow as the seat of Soviet power, while the five red stars, enlarging in size but diminishing in color intensity as they move further from Moscow, represent the increasing strength of Communism in Russia during the years 1920-22. The stars also serve as symbolic shields, apparently deterring attacking forces that emanate from Poland, Ukraine, and the Volga region. The red flag with the gold emblem of the hammer-and-sickle in the upper hoist quarter, and the letters Р. -

Unit on Communism

INFORMATION CARD To understand the history of the 20th century in general, it is Defining characteristics of a communist regime important to know what communism is. Ideas similar to communist ones (about equality between citizens Land, banks, industry and resources are state property. During the and a fair political system) emerged already in ancient times. Only in founding of the regime nationalisation takes place (the state power the second part of the 19th century did philosophers Karl Marx and confiscates all private property). Friedrich Engels develop the theory of communism. The basic idea is that capitalism is the last phase of society and that as the result of a Communist Party – the only and dominating party, all other political workers’ revolution, a classless society would be established. In parties are forbidden. communism, all property would be shared, everybody would be equal Cult of the party leader. and everybody would receive according to their needs. Based on these Central planned economy. In the Soviet Union the economy developed ideas, the workers’ movement in Russia, led by the Social Democratic according to the five-year plan. Economic decisions (even petty issues Workers Party, grew. like the name and price of a new cake) were accepted by the ministries In the autumn of 1917, under the guidance of Lenin, the left wing in Moscow. of the Social Democratic Party, known as the Bolsheviks, came to Aggressive foreign policy. power in Russia with an armed coup d’etat. This turned into a dictatorship Industrialisation, especially developing heavy industry (industry that of the Communist Party (all federal decisions were accepted by the produces not for consumption, but for production itself). -

Berlusconi of the Left? Nichi Vendola and the Narration of the New Italian Left

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Gerbaudo, Paulo (2011) Berlusconi of the Left? Nichi Vendola and the narration of the new Italian Left. In: NYLON research group seminar: Alumni-led seminar | Politics and myth, March 17th 2011, LSE - Tower 2, Cities Programme. [Conference or Workshop Item] First submitted uncorrected version (with author’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/7570/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

1 a Holy Relic of War: the Soviet Victory Banner As Artefact Jeremy Hicks Since 1965, the Centrepiece of 9 May Victory Day Celeb

1 A Holy Relic of War: The Soviet Victory Banner as Artefact Jeremy Hicks Since 1965, the centrepiece of 9 May Victory Day celebrations in Moscow has been a parade on Red Square in which the Victory Banner raised over the Reichstag on 30 April 1945 is ceremonially displayed by a guard of honour before the watching public. The banner is a red Soviet flag bearing the hammer and sickle emblem, with the name of the unit that raised it added in white1. Newsreel and still photographic images of the raising of the Victory Banner over the Reichstag became a central symbol in the 1960s birth of what has been called a Soviet war ‘cult’ (Tumarkin 1994, 137). More recently, the actual banner and - since its official adoption as an official state symbol in 2007 - replicas of it have played an increasingly important role in articulating and disseminating the Soviet and post-Soviet Russian view of victory in the Second World War, the Soviet dimension of which has long been referred to as the Great Patriotic War. This chapter is an attempt to understand how this flag came to acquire such symbolic resonance, and to trace how its place within the practices of Second World War commemoration that have evolved since May 1945. The introductory section adumbrates a theoretical approach premised on the notion that national understanding of the past is constructed in part through the selection and mediation of symbols. I then trace the fate of the Victory Banner from its initial journey to Moscow in May 1945, examining its installation in, what is now known as the Central Museum of the Armed Forces and the ways in which the changing approaches to displaying it in the 2 years since have variously constructed this symbol’s meaning amidst changing societal attitudes to the war. -

Art & Activities / Hammer & Sickle: Interpreting Symbols and Meaning

Art & Activities / Hammer & Sickle: Interpreting Symbols and Meaning Overview: This lesson features artworks that incorporate powerful symbols: the hammer and sickle and the American flag. Students first deconstruct how the symbol is treated in the artwork and then infer meaning by com-paring and contrasting the aesthetic qualities of the artworks. This lesson can be extended into a research project into the historic and cultural contexts behind each one of the featured works. Grades: 8 to 12 Subjects: Art, Aesthetics, History, Social Studies, Language Arts. Pennsylvania State Standards: Arts and Humanities: 9.2. E Analyze how historical events and culture impact forms, techniques and purposes of works in the arts 9.2. J Identify, explain and analyze historical and cultural differences as they relate to works in the arts Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening: 1.6.11 D Contribute to discussions Objectives: • Students will list and categorize common symbols and meanings • Students will intuitively respond to works of contemporary art • Students will connect symbols to meanings • Students will associate personal feelings and thoughts to artworks • Students will create new meanings for symbols based upon personal responses • Students will formulate ideas for new artworks referencing either the hammer and sickle symbol or the American flag © The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh. All rights reserved. You may view and download the materials posted in this site for personal, informational, educational and non-commercial use only. The contents of this site may not be reproduced in any form beyond its original intent without the permission of The Andy Warhol Museum.